.

There is scant information available to show just how strong the early feeling for women’s suffrage was in Launceston or the area as a whole. The first reported mention in the area was at Holsworthy on July 5th, 1908, at a public debate on “Shall women have the vote?” After a lengthy and lively debate a resolution, condemning the extension of the vote for women, was passed with only one dissentient.

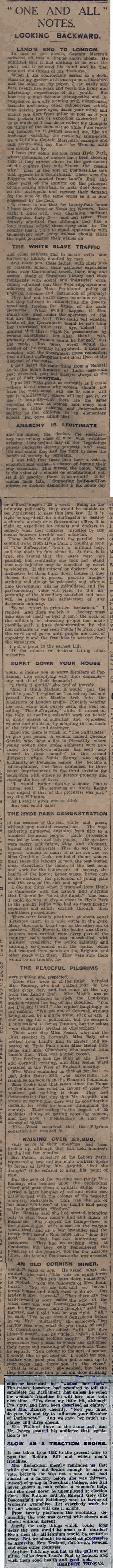

Of course, by this date, a national movement, driven by the Women’s Social and Political Union, had already taken root, bringing the whole issue of women’s enfranchisement to the public attention. Ironically, given that it was a Liberal government that was refusing to give the female vote, it was largely with the Liberal women that sympathies lay for the suffragette movement, as is evidenced in this September 1908 editorial from the Cornish and Devon Post.

It was for good reason that many of those sympathetic to the suffrage cause, kept their feelings to themselves, possibly not to expose themselves to ridicule as was the case at many of the local carnivals (below report in November 1908 Launceston carnival), or outright disapproval as was the case a Holsworthy ‘social’ in December 1908 whereby a Mrs E. O. Kingdon on opening the proceedings, she touched on the suffragette question and waving a banner with the inscription “Votes for women” she was promptly hustled off the platform by ‘2nd class constable Kingdon.’

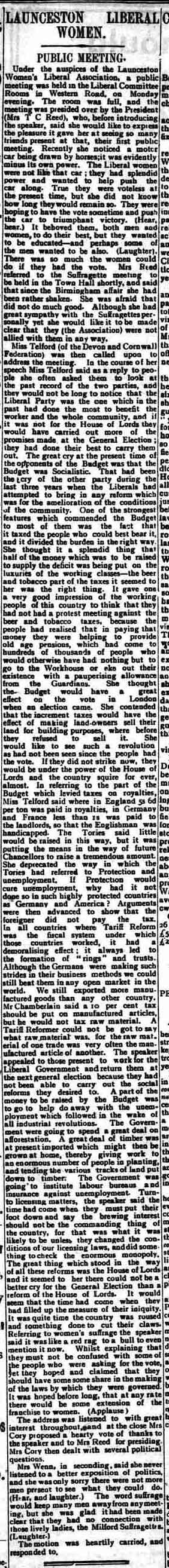

However, one Launceston woman, Mrs Hannah Reed, wife of Launceston businessman Thomas Reed, took up the mantle for the suffrage movement by inviting Bristol lady, Mrs Martin (possibly Selina Martin), to speak on the suffrage question at the annual meeting of the Launceston Women’s Liberal Association held on December 4th, 1908. Mrs Reed, on introducing Mrs Martin, condescendingly began “it was quite right to say that women in the past had not been educated and were not qualified for the vote; they were not fit.” She considered the vote a solemn trust, and when they got it – for they were going to get it in the future- she hoped they would be better qualified to use it, and thought they would do it wisely and well. “Men were kinder to them than some women, who thought suffrage was a very terrible thing. Suffragette was not suffrage.” Concluding Mrs Reed said “when they held their first meeting in 1893, women’s suffrage was on the agenda. The women did not want the vote for themselves, but entirely for others.”

Mrs Martin took to the stage and from the very beginning made it clear that she wasn’t a suffragette, but one of the Liberal Federation of workers. During her lengthy address, she said: “I do not think it was right that men should legislate on women’s labour unless women had the vote.” She felt that the suffragettes held wonderful courage and conviction and that she did not feel so cross about it as some people. She went on to talk about the Boards of Guardians, emphasising that there were only 14 women inspectors in the whole of England and that it seemed unusual for men to inspect babies “for men could be taken in by any woman.” She also stated that at that time no married woman outside London was able to serve on municipal councils. “A good many men still wanted to be educated on the suffrage question.” After some time, Mrs Martin concluded by moving the following petition, which was agreed to, be sent from the meeting to Mr Asquith and the M.P. for the division:-

“That your petitioner believes that the Parliamentary Franchise should be extended to women. Wherefore your petitioners pray that your Honourable House will include a clause giving the Parliamentary vote to women on Democratic lines in the measure dealing with Electoral Reform, promised by the Prime Minister during the life-time of the present Parliament.”

A Mrs Cory in seconding the motion referred to what she described as the awful horrors of the living-in system in large towns. “If they all knew what girls had to put up with, they would not wonder that her blood boiled when she read about it recently. The matter would be brought before Parliament when the women had the vote,” she said.

The M.P. for the division was Mr Croydon-Marks and he made his views on the suffragettes quite clear when at the annual meeting of the Cornish Union of Women’s Liberal Associations held at Launceston the following April, he responded to the president Mrs. Homan’s address where she had stated that she looked forward to the day when there would be no need for associations of men and women, when they would all work side by side. Croydon-Marks replied that the suffragettes, with whom, no one present had any sympathy. He believed that the advancement of the cause of women could be obtained without resorting to methods of violence which made ruffians of them. People recognised that in politics there were sentiments that men could know very little about and spheres where women could do useful work.

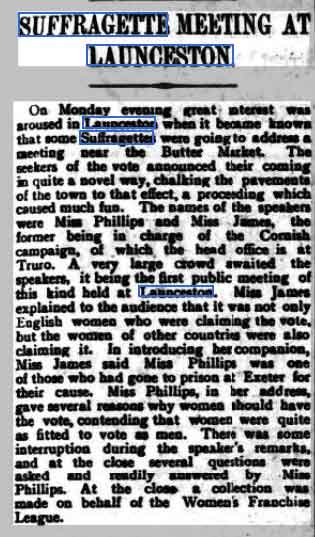

August the 23rd, 1909 marks the first ‘suffragette’ meeting in the town or rather an address given by the Misses Phillips and James respectively. To a very large crowd near the Butter Market in the town centre, Miss James, who was the Cornish campaign manager, introduced Miss Phillips as being one of those who had gone to prison at Exeter for their cause. Miss Phillips gave an address that gave her reasoning why women should have the vote during which there were several interruptions and at the end of her speech, she readily answered the many questions raised. Finally, a collection was made on behalf of the Women’s Franchise League.

Hannah Reed again presided over a meeting of the Launceston Liberal Women’s Association where she offered her personal sympathy of the suffragettes whilst at the same stating that the association were not allied to them. She was particularly upset at a recent incident when Prime Minister Asquith visited Birmingham’s Bingley Hall to address a Liberal meeting there. Prevented from gaining access, members of the Women’s Social and Political Union used alternative tactics were then employed in order to gain access to the meeting: two of the women climbed onto the roof of a nearby house and threw roof slates at Asquith’s car. Hannah said of the incident that she was quite shaken and felt it did not do much good.

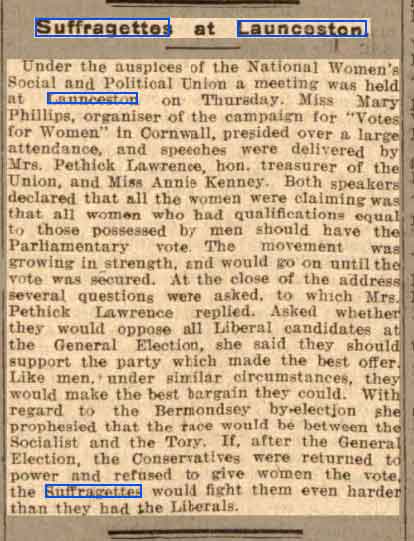

A couple of weeks later a more organised suffragette meeting was held before a large number of people, under the auspices of the National Women’s Social and Political Union and held this time in the town hall. Mary Phillips returned to chair the meeting with the guest speaker being Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, the treasurer of the Union. In the course of a long address, Emmeline said the only thing that appeared to be objected to was the way in which the women were trying to obtain the vote, for it was taken as a matter of course that women should have the vote. The women were asking for the removal of the disability of sex. They were not asking for any favour, but for the barest justice. Some people appeared to think that the suffragettes had a sort of vendetta against the Liberal party. “I thought somebody was thinking that.” They had nothing against the Liberal party, and she had no hesitation in saying that they (the women) were better Liberals than anybody. The Liberal principles were that taxation and representation should go together, but the women who were taxed had no representation. “Trust the people” was a good principle, but why didn’t they trust the women? They wanted to bring the Liberals back to these principles. The Liberals ought to look on the suffragettes as angels in disguise. They were entertaining angels but did not know it. The right of the people to tax themselves was a principle which was on the lines of the suffragette movement. Men were ruling just because of the accident of birth – just as the Lords were Lords by accident. Men were not born males because of their great wisdom. Some people said they did not like the methods the suffragettes were using – but the suffragettes disliked it more, and suffered more because of it. But when the men did like the women’s methods, they didn’t care how long they went on. The women did not like violence; they liked peace even more than man. It was true they were bound to win because there were women who did care not what was done to them. The vote was bound to come if they were ready to suffer anything – really prepared to die. She went on to say that they were completely dominating the Bermondsey election, and she prophesied that the fight would be between the Socialist and Tory candidate. Reference was also made to the refusal of women to eat in prison, which amid laughter, Emmeline called the last effort of passive resistance.

Miss Annie Kenney was the next to speak. “The women wanted the vote,” she said, “to protect them in the industrial world” continuing. “Women should have the same chance of political education and development as the men. We are fighting because we want to serve our country and because we think it will be for the welfare of the country and the children, and make it a brighter world than at the present time” she said finishing her short address.

There then followed a question and answer section whereby Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence returned to centre-stage. The first question came from a gentleman in the audience who asked how the women could obtain what they desired by supporting people who were opposed to their desires. Emmeline replied that they supported nobody. They simply fought against Government who were opposed to them. The next question was did she think it fair of the women of this country to expect the Liberal Government to set aside all its business for the mere question “Votes for women?” Emmeline answered in the affirmative: no question could be properly settled until the women had the vote. The Budget should not be passed before the opinion of those to be taxed was sought, so “Vote for women” ought to come before the Budget. Another question was did she agree with the Budget? Emmeline replied that she could agree with no Budget that levied taxes without representation. In answer to further questions, she said the women would oppose any Liberal candidate because the Liberal Government had not given them the vote. It did not lie with a private Member. A private Member had no power to bring in a bill. That was a bit of political wisdom they were teaching the men that night. If the Conservative got in and refused to give them the vote, the women would fight them harder still, as they would then be stronger.

Mr James Treleaven junior, in answer to a question, was informed by Emmeline that the women would vote at the next election for the party who promised them votes, She did not know what suffragettes would do if both parties were of the same mind. “Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.”

To a question asked by a Mr C. Ball whether they were not expecting too much to get the whole of the Government on their side instead of getting one at a time, Emmeline replied that there was no way but to get the whole Government. Walter Palmer asked if it was intended to give votes to women who do not pay taxes? Emmeline said the demands were limited to those women who fulfilled the qualifications men fulfilled. A Miss Woods asked on what ground it was thought votes for women more important than measures like that of Licensing and Education? Emmeline replied that there could not be reforms until those people whom they concerned were free. She added that 80 per cent of the women enfranchised would be earning their own living. She agreed it would be better to take half a loaf than none. There was no way of supporting measures but through the ballot box.

There is no doubt that the votes for women campaign had a lot of support from many in the area as this poem by Mr John Davey of Lifton penned in 1910 demonstrates in a light-hearted way:

If every man had a job

And every labourer 30 bob,

With jam and cream for tea;

If everyone could have a roast duck,

If farmers never had bad luck,

How happy we would be!

If doctors never charged for pills,

And tailors never send in bills,

And everything was free;

If miser never hoarded wealth,

And loved his neighbour as himself,

How happy we should be!

If Lloyd George could grow his ships,

From cherry stones or apple pips,

And we were taxes free;

If old age pensions could be found,

By simply digging in the ground,

How happy we should be!

If lovely woman had a vote,

What blessings we should quickly soak,

What changes we should see!

The husband man would mind the kids,

Wash up the cups and saucepan lids,

While wife became M.P..

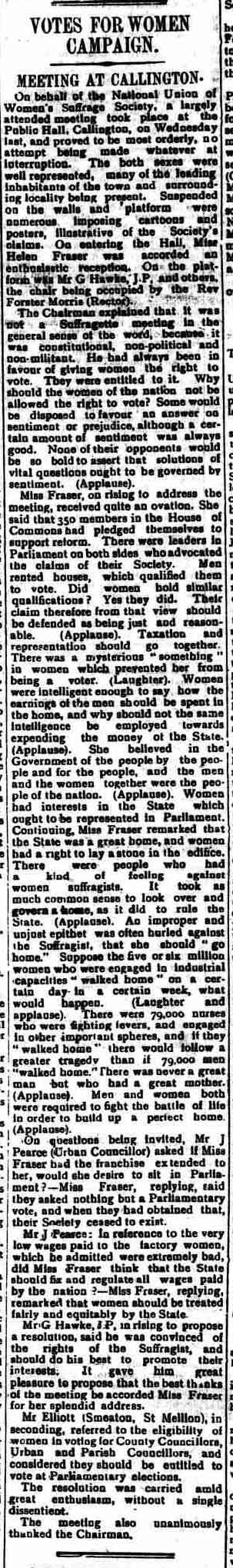

Further to the meeting at Launceston, the suffragette movement gained interest in neighbouring towns with one being held on behalf of the National Women’s Suffrage Society at Callington on April 30th, 1910.

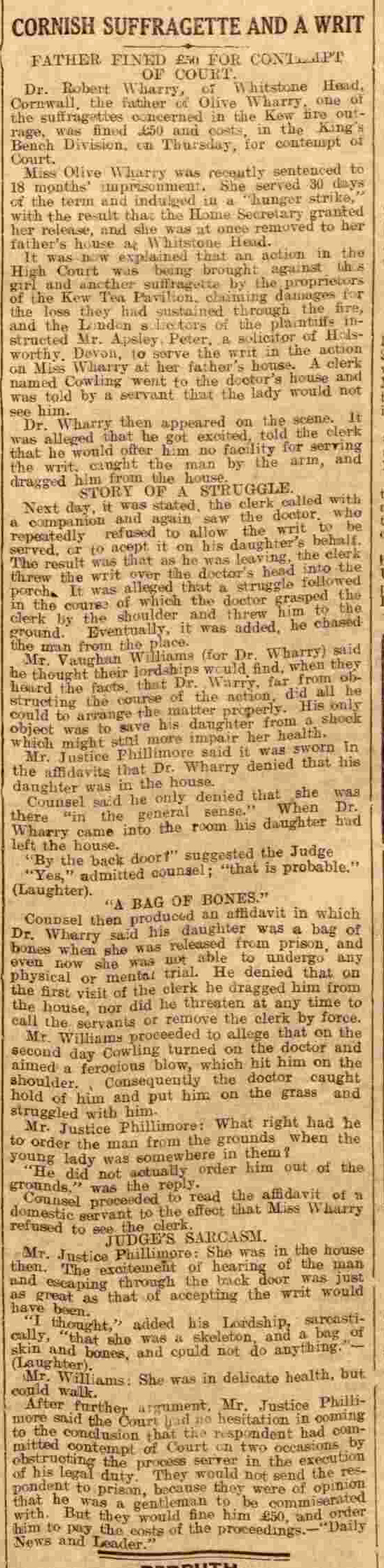

In fact, meetings took place throughout Cornwall as the support took hold within Liberal progressives and many educated young women took up the cause. One such young lady was Olive Wharry of Whitstone Head, aka ‘Joyce Locke,’ who received an 18-month sentence at Holloway prison, for setting fire to a refreshment pavilion at Kew in 1913. The daughter of Dr Robert Wharry of Whitstone Head, she went on hunger strike and after thirty-two days’ was released on Royal warrant. Being quite ill from her prison protest she returned home to Whitstone. Here a writ was attempted to be served upon her by the pavilion owners, but her father being concerned for her health, prevented the execution being carried out and for this, he in May 1913, was fined £50 for contempt of court.

1913 was also the year of the big march from Lands End to London by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. During their march, they faced some hostility such as when they attempted to address a crowd numbering ten thousand at Camborne. Here, when Helen Fraser got up to speak she was pelted with eggs. The group of suffragettes number around ten escaped some hours after being shut up by disguising themselves and making their way from the backdoor of a hotel.

However, not all receptions were like this for the marchers as they journeyed through the counties. By the time they had reached Hyde Park for a massive rally, nearly 15,000 people had seen them, some even walking in support with the ladies. 46,000 signatures were also collected in support of the women’s cause. The rally held on July 23rd, itself was also a success, with over 50,000 attending.

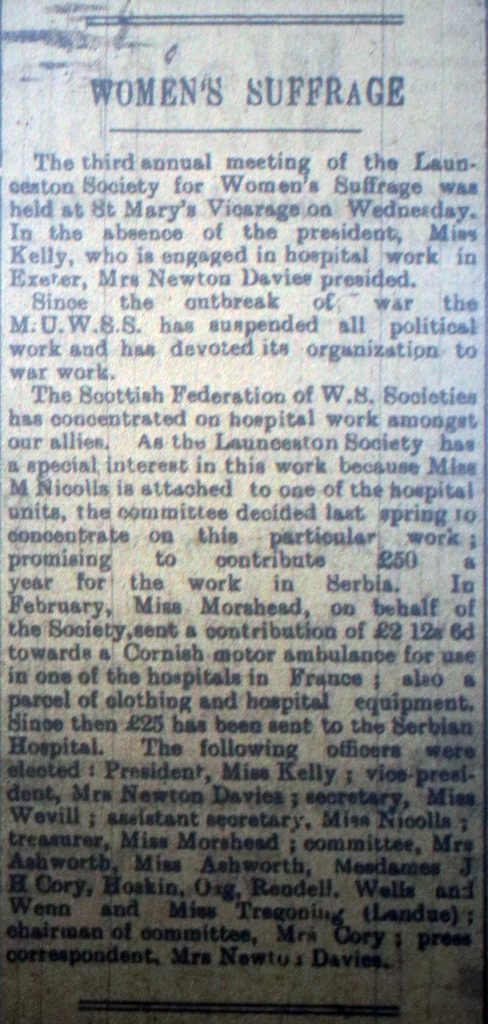

It was around this time that ‘The Launceston Society for Women’s Suffrage’ was formed with Miss Kelly as the president, Mrs Newton Davies as vice president, Miss Wevill, secretary, Marion Nicolls, assistant secretary, and Miss Morshead, treasurer. The committee was made of Mrs Ashworth, Miss Ashworth, Mesdames J. H. Cory, Hoskin, Oag, Rendell, Wells and Wenn and Miss Tregonning (Landue); Mrs Cory was the chairman of the committee and Mrs Newton Davies the press correspondent.

But just as support for the vote for women was gaining momentum the First World War struck with the result that all activists turned their attention to supporting their country. However, the cause was never far from the mind with activist continuing to hold meetings. The Launceston Society for Women’s Suffrage held regular annual meetings throughout the duration of the war. Many of its members were themselves away performing their own war work such as the Societies president, Miss Kelly, who was engaged in hospital work in Exeter. Another member was pharmacist Marion Nicolls, who volunteered to work for the Scottish Women’s Hospital led by Dr Eleanor Soltauwas in Serbia. Marion along with everyone else was taken prisoner by the Austrian’s in 1915 and released in January 1916. Due to Marion’s work in Serbia, the Society promised a figure of £50 per year for the Scottish Women’s Hospital’s work in Serbia.

As we know, the war in a strange way paved the way for the emancipation of women, with many taking over from the men in industry. After the war, the world had changed and at last, in 1918, a coalition government passed the Representation of the People Act 1918, enfranchising all men, as well as all women over the age of 30 who met minimum property qualifications. Full equal voting wasn’t achieved until 1928 when the Conservative government passed the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act giving the vote to all women over the age of 21 on equal terms with men.

Visits: 250