.

Some several centuries ago (1478 being the first mention) there was held by the Corporation of Launceston some property or land called the ‘Aftermath property’ upon trust for the personal benefit of the members of the Corporation and their widows. (Aftermath = Aftermoweth – land which has been grazed, then drawn and cut for hay, and then let to individuals to allow animals to graze on the after growth of the grass. Also to allow householders to carry fern and gorse for firing.) The “Aftermath Fund” was set up from the fines and rents of the above mentioned, and was meant to pay for repairs, etc, for the church, the town roads, town lighting, water, and towards keeping paupers in the parish. Park Mill – possibly this was situated in the valley below Western Road, where signs can still be seen of the old mill pool and the mill a little further north of the stream dividing (anciently) St Mary Magdalene parish from St Thomas parish. Clateryn Walls – the area near Bangors quarry, later used as the town rubbish tip. The land (see 1880 map below) was the commons of Pennygillam, Longlands, Haye, and Windmill.

An Interrogation of 1478, translated by Richard & Otho Peter into their book of Launceston:

The question is asked if anyone knows of any lands given to the Mayor and Commonalty of Launceston and their successors, this is the answer given:

“To the first Interrogatory, sworn and examined, saying that he knows of no gift of lands to the Mayor and Commonalty other than that which is certified by the Commissioners of the Charity lands to the King’s honourable Court of Augmentation, whereof the King’s Majesty is seized according to the statute, nevertheless he said that the Mayor and Commonalty, by time whereof no mind of man is to the contrary, have had certain lands and tenements called Town Lands, which are the Ancient possessions of the said Town, with lands they and their predecessors had and enjoyed according to the custom of the Town, that is to say, to the burgers and to their heirs and assigns for ever, paying to the Mayor, at every 12 years end, one English penny, and yearly the accustomed rent and service of the borough, certain of which possession of lands has been, before the time, enclosed and set to rent, to bear the yearly necessary charge of the Town; and another parcel of this said possessions, called the Open Commons, lying in “quellytts and folongs”, whereupon the inhabitants do maintain their tillage, and have grass to make hay for their cattle the winter time, and upon these commons every inhabitant do freely pasture with his beasts, according to the customary stent of the town, after that the corn and hay is carried away, and this is the customary stent:- The Mayor for the time being to pasture with 12 beasts, every Alderman with 10 beasts, every burgess that has been Portreeve with 6 beasts, every other burgess with 4 beasts, and every inhabitant with 2 beasts, without paying any thing for their pasture.

Also there is another parcel of the said commons, of furze and heather, called Skardon, whereupon every inhabitant, as well the rich as the poor, may freely pasture only with 2 beasts during the time that the said quellets are in tillage, hayed and lopped; And upon this Common every inhabitant of the Town may, with hook and scythe, cut and carry way upon his back as much furze brake and heather as his need shall require, without paying anything for it, so that he carry none with any cart or horse.”

The Second Interrogatory asks if anyone knows who gave the said lands:

“To that the said Mayor and Burgesses say that they know not by whom it was given, nor who made it to be customary land, nor who built the Town first, nor who made it a free borough, but they say that they hold the said borough with the appurtenances, of the King’s Majesty in Chief, to fee-farm, as parcel of the Dukedom of Cornwall; and further say that they never heard but all the said lands did pertain, from the beginning to the said Town for the comfort and use of the inhabitants thereof, which they have ever had and enjoyed accordingly, without interruption of any man: And that the said lands be of the yearly value of fifty pounds, or thereabouts, beside the profits of the markets, fairs, and courts, and casualties”.

The Third Interrogatory enquires as to the use of the said lands:

“To that the said Mayor and Burgesses say that the said land, as they have heard old men report, was appointed to be used as above mentioned, but for the welfare of the inhabitants of the said Town, as the rulers thereof thought most convenient by their discretion.”

The Fourth Interrogatory is as to what the profits were used for:

“To that the said Mayor and Burgesses do say that they and their predecessors have employed the profits of their possessions as here follows, that is to say, upon the reparation of their church, Townsmen’s houses, paving of the streets, mending of bridges and highways to the Town adjoining, to the funding of men and guns when the King’s grace do require it; Also to pay the tenths and fifteenths of State taxes [Rates] where there is any granted, to pay the Fee Farm of the Town, to the necessary furniture of the Mayor’s Fee, the Recorder’s Fee, and the fees of the other officers of the Town: To the maintenance of the Almshouse, wherein be 5 poor people, towards the funding of the prisons in the King’s Gaol, and to divers other Godly and necessary purposes, as by the Mayor for the time being has thought most necessary and convenient.”

In 1512, the tenements in Hyllond appear to have been – the Park Mill, half of Pennygillam, Clateryn Walls, Charkefarthing, Ryalton, Downhevyde, Est Hay, John’s Close, and Penhole. In Lyon were Bastret, and Wyndmyll head, and a tenement near the Quarry. (John Trelauny, rector, and the Prior of “Synt Lenard” were two of the tenants).

Rents were also received by the Borough Council from 101 tenements scattered in Page – 25, Hey – 26, Hillond – 13, Longland – 12, Windmill – 23, Lyon – 9, two closes near Carford, among others around various parts of Dunheved.

Scarne: an uncultivated common until 1755, when it was proposed to build a workhouse on part of it.

In 1784 the then members, in consideration of small remuneration, and on the condition that its income should be applied towards ‘the repairs of the church, the streets, and other purposes for the convenience of the inhabitants.’ St. Mary Magdalene Church was named the first priority of the Trust, and the members of the Council and their widows wished it to remain as such. St. Mary’s at this time, was the Mayor’s chapel and belonged to the Corporation, and all their then property, which consisted, among other things, ‘of profits of markets, fairs, and courts and casualties,’ was liable for, and, where necessary, was applied to the repairs of the church, and also in payment of the organist, clerk, sexton, and ‘for all the administration of the church.’ By a statute of George III (1784-5) the rights of the burgesses in the Hydeland were absolutely and finally vested in the Mayor and Aldermen of the borough for purposes of sale and lease. The seventh section of that statute recites and enacts as follows:

Whereas there are, within the said Borough, several Common Lands, called Great Pennygillam, Little Pennygillam, Hay, Windmill, and Longland, the aftermowth of which hath of ancient right and custom, for time immemorial, belonged to and been enjoyed by the Mayor, Aldermen, and free Burgesses of the said borough, and the widows of the deceased free Burgesses, for depasturing all cattle (except hogs) from the time that the several crops of grass and corn are removed, to the twelfth day of January in every year; but, for want of proper regulations, the said depasturage produces very little benefit or advantage to the several persons entitled thereto; be it threrefore enacted, that from and after the passing of this Act all aftermowth of, or right of depasturing cattle on, the said common lands, shall be and is hereby vested in the Mayor and Aldermen of the said borough for the time being for ever, free from all right and claim of common of pasture by the Mayor, Aldermen, and free Burgesses of the said borough, and the widows of free Burgesses; in trust nevertheless to sell and dispose of the said aftermowth or right of depasturage, or otherwise to lease or demise the same, by writing, to any person or persons, for the best price or rent that can be reasonably had or obtained for the same, and to apply the money arising by such sale or rent, from time to time, in manner following (that is to say), in the first place, in making satisfaction and compensation to such persons, for their right and interest in the said aftermowth or right of depasturage as shall claim and demand the same; and the remainder of the money arising by such sale or rent to be applied towards repairing the church, repairing and lighting the streets, or any other purpose, for the ornament of the said town, or convenience of the inhabitants.

The chief part of the ‘Aftermath’ and pasturage of the common lands was sold soon after the passing of the Act, with the net proceeds of the sale invested in the purchase of £1791 6s. 6d. Three per cent. Consols, with it now named as the ‘Aftermath Fund.’ Longlands and two pieces of Hay Common were all that remained.

The living of St. Mary Magdalene was sold to the Duke of Northumberland in 1847 for £400, under the provisions of the Municipal Reform Act of 1830. The corporation applied the whole of the purchase money towards building a new Market House (The Butter Market below) for which they then derived an annual income in rental.

The Corporation kept the ‘Aftermath Funds’ separate from their other property, and first applied it towards the repairs of the church, and only when they had a surplus in hand was it usually applied to other purposes. In 1809-10 the iron railings around St. Mary’s church were purchased from the Tavistock Foundry, at a cost of £222 8s. 3d.; and in 1839 the lime-wash was removed from the granite pillars of the church. On October 30th, 1852, the Corporation sold £513 5s. 3d. of the ‘Aftermath fund,’ giving the proceeds towards the restoration of St. Mary’s.

Part of the Municipal Reform Act stated that Town Councils should give up all charities to be vested in Trustees which were to be appointed by the Court of Chancery. ‘The Aftermath Fund’ was considered such a charity, and in 1859 the Court of Chancery decreed that this ‘Aftermath Fund; was a Church Charity and appointed only Church of England Trustees. These Trustees then applied first to the repairs of St. Mary’s, and if a sufficient balance was in hand to the churchyards and other purposes. When the living was sold, and the Town Council had secured the purchase money of £400, it was then considered that all property of the Corporation except the Aftermath was then released of not only their liability to the repair of the church, but also of their liability to pay the organist, clerk, sexton, and all other church expenses including the offertory which was of some contention (below article’s on the aftermath fund from the Launceston Weekly New October 23rd and 30th 1858. ).

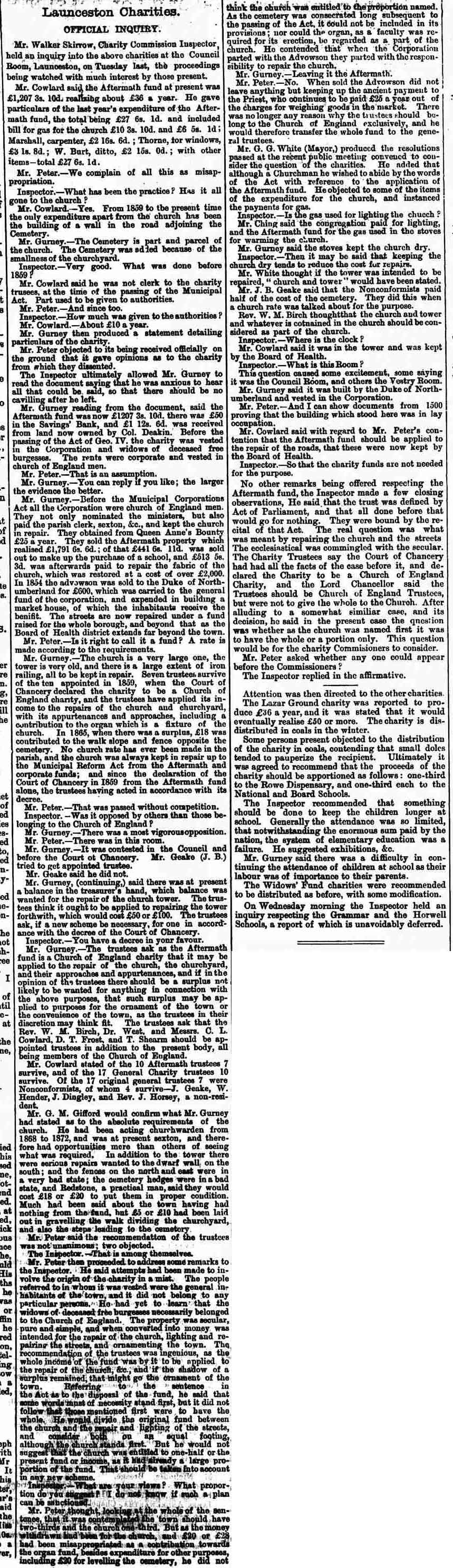

In 1875 there was further discourse (above) at the alleged misappropriation of the fund when the trustees agreed to give £28 towards the purchase of a new organ for St. Marys. With this and the fact that no monies had been made available from the fund since the trust had been set up, the town council decided to apply to the charity commission to look into the matter. By 1876 the fund stood at £1,207 3s. 10d. The charity held their inquiry on April 25th, 1876 (full report below). After lengthy discussions, the Inspector, Mr Walker Skirrow, ruled that it would be for the Charity Commissioners to decide as to how the fund should be apportioned.

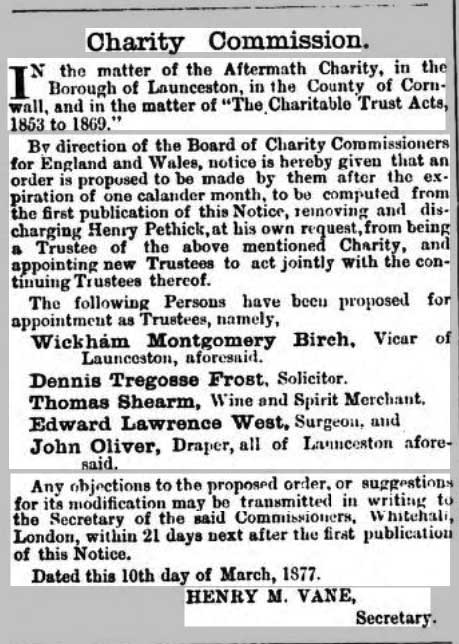

In March 1877 five new members were appointed to the trust with one, Henry Pethick resigning.

The Charity Commissions contended that it was a church trust and as such the trustees should all be churchmen. Two years later the fund was used to pay for the scraping and re-pointing of St. Mary’s Tower by the Launceston builder, William Burt, to the sum of £110.

By 1880 relations between the corporation and church broke down over the use of the Guildhall which was then located between St. Mary’s church and tower. This hall was built by the Duke of Northumberland (who paid for the total construction cost) in 1850 and was intended for the use of the town council with the church being allowed access to enable the vicars robing. But over the following years, the church slowly laid claim to the building leading to fierce arguments. On several occasions during the 1870s, council meeting’s were interrupted by church people entering the room which led to the adjoining door to the church being locked. Such was the fallout, the Bishop gave permission for the church people to smash it. The impasse had grown to such a state that by 1880 the borough council had decided to build a new Guildhall on land below Noah’s Ark on Western Road. In fact, plans to transfer the Guildhall from the corporation to the church were made in August of 1878.

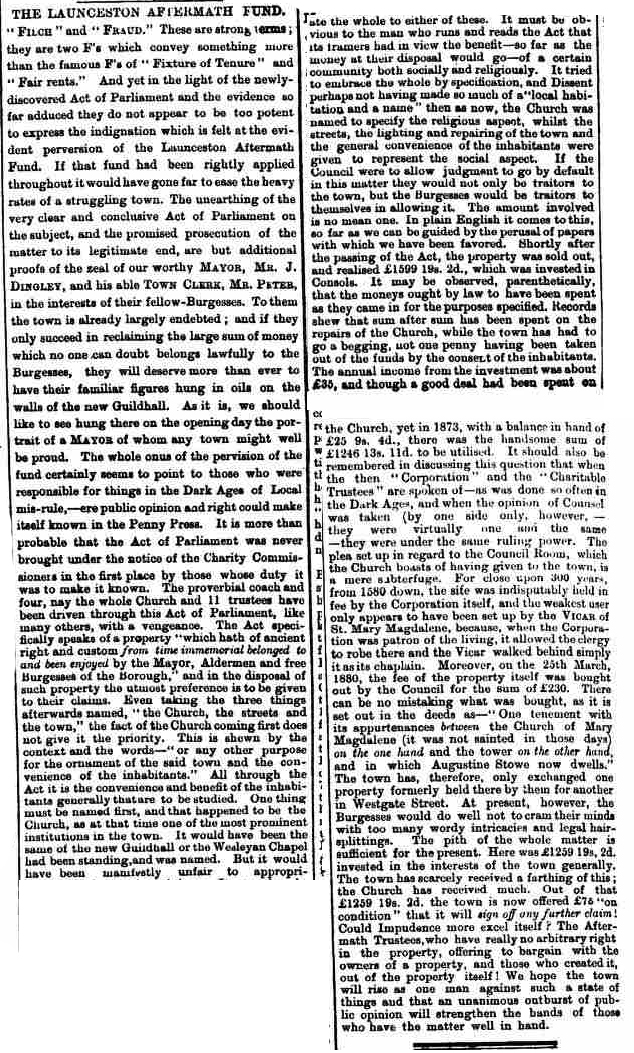

The council approached the Aftermath Trustee’s seeking financial assistance from the fund. The trustee’s, in turn, repudiated the right’s of the council to the fund but offered £75 on condition that it would in future hold no further claims on the fund. At a very heated quarterly council meeting in March 1881 (Cornish & Devon Post April 2nd 1881) the whole situation was debated.

The transfer of the old Guildhall and property that the Duchy of Cornwall held eventually took place after some five years of negotiations and the new Guildhall was duly opened in 1882 but the question of the aftermath funds appropriation was still largely felt unanswered. With the trustees failing to file any accounts in 1874, 1876, 1877, 1880 and 1881 contrary to Charity Commission’s rules, the town council appointed a committee to inquire into the matter in February 1885. The committee duly reported recommending that with a view to a compromise, the trustees be invited to join in an application to the Court of Chancery for a scheme to divide the aftermath monies in accordance with the spirit of the local Act of 1784 – that at least one-third of the fund might be applied to the town in any division, consideration to be given to the fact that large sums out of the fund had already been applied entirely to the church.

A decided split within the town ensued with many of the church being quite angry at this attempted takeover by the ‘Liberal’ set of the town council. It was cited that the fund was but just sufficient to provide for the repairs of St. Mary’s which left little over for any of the council’s projects, such as contributing towards the construction of a ball-room (Town Hall). In a letter countered to the report, the aftermath trust clerk , Charles Grylls, in refusing the compromise, suggested ‘that when the living of St. Mary Magdalene was sold the whole of the purchase money was paid to the corporation; that previously to that the whole of the corporate fund was liable for the maintenance of the fabric of the church; that the trustee’s had been advised that the sale of the living did not relieve the corporate fund from that liability; and that as the Town Council had so frequently attempted to divert the Aftermath funds from their application, they considered it a duty, in the interests of the church, to move the Charity Commissioners to inquire into the extent and trust of the corporate property which was held for charitable purposes, and to ask the Commissioners to invest that property an as to be under the control of the trustees, and to relieve the town entirely from its administration.’ The town council wishing to avoid litigation, wrote back to the trustees making them reconsider the matter, but Mr Grylls replied stating that he did see the necessity of placing the matter again before the trustees. In the meantime, without notifying the council, the trustee’s applied to the Charity Commissioners to appoint a new body of trustee’s, all of whom were churchmen. In the October of 1885, the council passed a resolution declaring that it was able that an application should be made to vary the Order of 1859, under which the Aftermath Fund was administered, and directing the town clerk to forward a petition to the Charity Commissioners, asking their concurrence in any necessary proceedings. That resolution was subsequently confirmed by a public meeting.

The Charity Commissioners then agreed to join the council in an application to the Court of Chancery for an order to vary the scheme on condition that the council guaranteed the payment of the Attorney General’s costs.

The Court of Chancery, in the end, decided that the fund was indeed a church and subsequently the trustees were made up of churchmen. After this point, no records can be found with the annual meetings being conducted in private. Various requests to the trustees were made such as the cost to repair the clock in St. Mary’s tower, but from 1888 the trustees became very secretive. In 1891 payments were made to repairs to St. Mary’s, winding of the clock and insurance to the sum of £20 16s. 10d. The same year a begrudging payment was made for the repair of the Bowling Green Cemetery wall in Horse Lane (Dockacre Road) and again in 1896, even though on both occasions the churchwardens attempted to pass the cost to the ratepayers (below). One can assume that the continued running costs of St. Mary’s such as the clock repair, soon consumed the fund but there is no further record of exactly how it stood or how or when it was wound up.

Visits: 24