By Otho Peter July 24th, 1909 from an article in the Cornish and Devon Post .

“I am a friar of orders grey,

And down in the valley I live all day;

Myself by denial I mortify

I’m clothed in sackcloth for my sin,

With old sack wine I’m lined within

A chirping cup is my matin song,

And vesper bell in my bowl, ding, dong!”

It has not hitherto been known to modern readers that there was a monastery at Dunheved, as well as at Launceston. I have in other writings traced from its birth to its death the history of that once existing at the latter place (Launceston Priory), and now propose to give some account of that at the former.

Early in the fifth century St. Martin, bishop of Tours in France, received into the religious house of which he was the head, a novice named Britius, who at first gave great offence by his disorderly conduct, but eventually gained the respect of his brother monks. On the death of St. Martin he was chosen as one of two candidates for the bishopric, and as he obtained the most votes was duly elected. This caused jealousy on the part of the unsuccessful candidate, who forthwith spread slanderous reports in regard to sins which he alleged had been committed by Britius, one being that on a certain occasion he heard him say when threatened by St. Martin with hell fire if he did not repent, that fire would not hurt him. A trial was demanded, and to test the truth or falsehood of the charge the judges prescribed a new ordeal, which they named “the Fiery.” By this the bishop was obliged to hold hot embers in his hands and as these burned his flesh and made him yell, he was condemned and banished from his See for seven years.

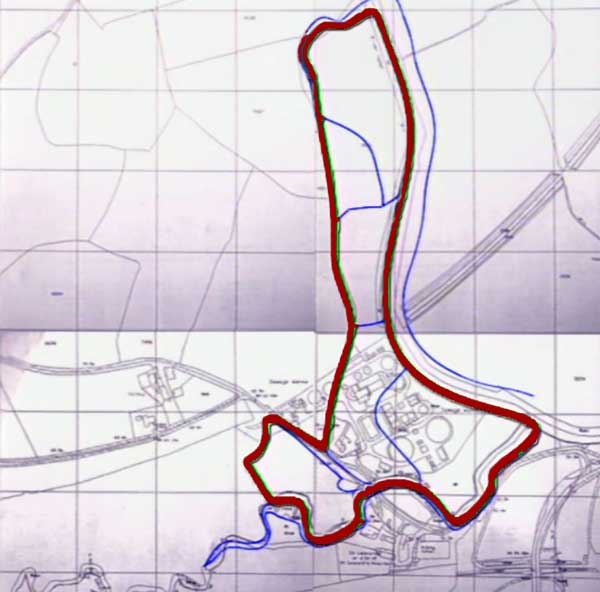

Britius thereupon took passage in a trading vessel and landed on the coast of Cornwall. He wandered inland, and on reaching the fortified station of the chief of the district at Dunheved, settled down there as a missionary. At this camp were many families who had been made captive or were imprisoned for religious and other causes, on whose wretched , especially that of the women and children, the bishop had compassion, and in order that their sufferings might be alleviated he asked the chief to grant him a portion of his borough outside the camp on which he might build and endow a convent for them and a church for the other burgesses where they might pray and lead a more cleanly life. His request was readily assented to, and the land allotted to him was that now known as the Hamlet of St. Thomas. There on the south bank of the Kensey, Britius erected a church and monastery, dedicating it to St. Martin, and on the 13th November A.D. 436 placed therein those whom he named Friars of the Guild of Saints Martin and Magdalene, admonishing them to elect from among themselves a prior who was to be the head man of the establishment and to see that only burgesses of the borough of Dunheved were admitted, who at their entry were to pay a fee and agree to leave all they possessed to the monastery (the location Otho believed, was adjacent to modern day St. Thomas Bridge below).

On the completion of this good work Britius returned to his See at Tours and remained there until his death in the year 444. Just before he died he had requested his confessor Leonard to keep in touch with the Cornish Convent. This monk was also beloved by the people and subsequently became known as the patron saint of prisoners whose chains were said to fall from them at his command. If my require evidence as to the respect in which Saints Martin, Britius and Leonard were afterwards held throughout England they should refer to the calendar of the Prayer Book where their feast days will be found noted under the month of November.

The Guild of Saints Martin and Magdalene had continued to flourish and their Church to be attended by the burgesses of Dunheved for six centuries, when the Norman conquerors arrived and took possession of the land. These foreigners made Dunheved the seat of the eldest son of the reigning King and built a castle for him there on the site of the fortified station where Britius had lived as a missionary. They also caused the two local monasteries to be placed under the spiritual control of Norman monks, but this latter arrangement was so strongly opposed by the resident monks that the strangers were early in the 12th century, driven to build a new convent for themselves, and the site they selected for this was close to that of the St. Martin Convent where they would be within call of the soldiers of the Norman Earls at the castle should they require military assistance.

The new convent they erected was a much larger and handsome structure than either of the old local establishments, and as the rich French monks in it followed the then fashionable rules if the order of St. Augustine they were, of course, patronized by the members of the Norman royal house and the nobility. It was Henry I, who conveyed to them all the duties which had formerly been performed by the canons of St. Stephen at Launceston, together with their seal of office, but he did not interfere with the duties, or seal, of the Guild of St. Martin at Dunheved except in regard to the appointment of a chaplain for their church.

So matters remained until the days of Richard Cocur de Lion, Earl of Cornwall. That Prince had returned from fighting crusade wars, and as he wanted money to pay his warriors, he, on a certain occasion, journeyed West to see what he could gather from the mines, and the mint at the capital of his Earldom. In his retinue was a young man who had fought in the East and unfortunately brought home in his blood the awful incurable disease – leprosy. The royal party on their arrival at Dunheved appear to have been entertained at the new priory, for it was there that the youth was seized with faitness, and had to be left in the care of its brothers. “He is a leprous man, he is unclean. The priest shall pronounce him utterly unclean. And the leper in whom the plague is, his clothes shall be rent, and his head bare, and he shall put a covering upon his upper lip”- Lev :chap. xiii.

A fortnight after as people were entering the cloister gate for mutina, they were startled by hearing someone from within calling “Make way. Room for a leper. Room;” and while they stood aside the youth passed out clothed in sackcloth and holding a napkin before his ashen lips. As this stricken one crept painfully and slowly along the hamlet street crying “Unclean, unclean,” a friar of St. Martin’s saw him, and filled with pity at his plight, led him to his convent. Then a horrible thing happened – the plague spread like wildfire among the brothers, and the tainted place became so dreaded and shunned by priests and people that both the prior of Launceston and the authorities at Dunheved united in a request to the Earl for its destruction and removal to a spot further away. And thus it came to pass that in the latter part of the thirteenth century the old Church and Convent of Saints Martin and Magdalene in St. Thomas Hamlet was pulled down and two new sanctuaries were founded in their place, one thereafter known as the Hospital of the Guild of Saints Martin and Leonard, situated a mile from the town near the meeting of the waters of the Kensey and Tamar, and the other as the Infirmary Chapel of the parish of St. Mary Magdalene situated inside the walls of the town. The reason why this duplication had become necessary was that on the destruction of the monastery at St. Thomas, the burgesses of Dunheved were left without a parish church. By agreement for the transfer it had been provided that no chapel should in the future be built in the Hamlet, and as the burgesses were not willing to attend the priory church and could not agree on a site for a new fane, they decided to place the matter in the hands of the resident legate of the crown, one Bartholomew of the Castle, who awarded that the folks residing in the Hamlet should attend the parish church of St. Thomas close to their boundary, and that the other burgesses should build a new church for themselves.

The erection of the new church of St. Mary Magdalene was commenced about 1320, but not completed until 1339 in which year Bishop Grandisson dedicated its altar. It stood where the present church is now. Over the portal was no doubt carved a figure of St. Martin, and events in the life of that good Samaritan were depicted there when all but the tower of the 14th century sanctuary was re-built by Henry Trecarell in 1511.

Although the lepers of Saints Martin and Leonard were thence forward out of touch with the homes of other people they continued to retain their ancient rights as burgesses of Dunheved together with their seal of office and emoluments by way of alms. Their new hospital buildings, which are not referred to as having been on the land mentioned below as conveyed to them by the prior, were, I believe, on Dunheved or south bank of the Kensey close to the footbridge spanning the brook at St. Leonard of today, which led directly into the lepers graveyard on the north bank and also served as a means of communication between the two portions of the little estate. This comprised certain common or waste land of the Borough of Dunheved adjoing the road leading to Polston bridge on the South Bank, and an 18 acre plot on the North bank conveyed to the lepers by the prior of Launceston. The spiritual wants of the establishment were supplied by a chaplain appointed from the priory, and the wordly occupants of the stricken ones were regulated by priors whom they elected from among themselves, and consisted of farming, and fishing for salmon and trout in the rivers bounding the property. They held no communication with those outside excepting perhaps a word or two across the hedge with the messenger whose duty it was to bring them a daily loaf of bread and their quarterly alms. Generations of these poor helpless ones lived and died and were buried at St. Leonard for nearly three hundred years after its foundation there, and then a change came over their establishment, for, on the priory of Launceston being dissolved in 1540, the Corporation of Dunheved took the place of the priors as governors of the hospital, and they , I am sorry to say, appear to have neglected to supply the spiritual wants of the lepers, and also occasionally omitted to pay them their alms. This made it necessary for the prior of the hospital in 1609 to raise money by some other means, and the plan he adopted was to lease on lives a portion of his property to outsiders. At last they were driven to such straits that in 1648 a prior was bold enough to apply to the Justice of Assize for Cornwall from whom he obtained an order for the payment of alms that had been detained. So things went on from bad to worse until 1684 when a charter, the validity of which is disputed, was obtained from James II, whereby the Corporation were in the event of no leprous persons being in the hospital to have the revenues from its lands and tenements “for the use and better support of the poor of the Borough of Dunheved.” Soon after this, when leprosy happily died out in the neighbourhood, we find the Corporation availing themselves of the right supposed to have been given them by King James, for in 1697 they began to lease the estate and disburse the rent from it for various purposes, such as gifts to distressed soldiers and the like.

Having thus once taken hold they in 1710 increased their grip, for in that year the Mayor (John Bewes) and the eight aldermen who formed the Corporation, framed a by-law for themselves by which all the common lands of the borough were placed under their sole control. Nineteen years after the John Carpenter, mayor, became tenant of the hospital house and land continued to occupy it until 1755, when a fresh agreement was drawn up between him and the Corporation. Although I have not seen this deed it is probable that the hospital house and land on the south, or borough side of the Kensey, was then let to him as a separate holding. At any rate the 18 acre plot on the North side soon after appears to have come under the control of a new body constituted by Act of Parliament consisting of the mayor, aldermen, and five burgesses, and known as ‘The Guardians of the Poor.’

The southern portion continued to be occupied by members of the Carpenter, Cudlipp and Rowe families up to the year 1810, when Coryndon Rowe, mayor, lent the Corporation £400 at 5% to pay off a debt which they had incurred for work done at the church of St. Mary Magdalene and for the churchyard iron railings. Interest was paid on this for seven or eight years and then ceased, and I suggest that this portion of the Lazar Ground was conveyed to him in settlement and that he then retained the ancient seal of the lepers, which seal has on its representation of St. Leonard, and is now, I believe, in the possession of Miss Gurney of Trebursye.

When the Municipal Corporation Act of 1835 was passed still another change took place, the portion of the Lazar Ground on the North bank being then vested together with the other charities of the town in local Trustees for the use of the poor of the borough.

I must now make a slight digression concerning a bequest of £400 which in the sixties (1860’s) had been left by Sir William Carpenter Rowe, a relation of Coryndon Rowe, to be devoted for the best object for the benefit of Launceston that should commend itself to his executors. With the interest proceeding from this sum the executors rented a house in Southgate Square, which was known as the Rowe Dispensary, where assistance was given to those in need of medical help. On the want of an infirmary, in addition to the Dispensary, being locally felt, the Rowe family and others added money to the original bequest of Sir Willaim Rowe, and in 1871 purchased the site of and built the hospital which now stands adjoining the Western Road (now the offices of Potter, Baker), its trustees then being Messrs C. Gurney, H. M. Harvey and F. C. C. Rowe.

In 1880 Messrs Gurney, Geake, Ching, and Dingley, as trustees of the general municipal charities of Launceston, among which was classed the Lazar Ground, applied to the Charity Commissioners and asked their sanction to the placing if this borough tenement in their hands of the ‘Launceston Dispensary and Infirmary Trustees’ and as they consented, all that at present remains of the ancient Convent of Saints Martin and Leonard of Dunheved, except its seal, and the name of a November fair, is now owned by the Rowe Dispensary and Infirmary trustees. Through the actions of their forefathers the Town Council of Launceston were necessitated in 1897 to become tenants of thre acres their former property at St. Leonard for which the ratepayers now pay the trustees of the Infirmary £22 a year, and as the remainder of the Lazar Ground brings in another £24 the total recieved from it forms a nice little nest egg. The scheme approved by the Charity Commissioners runs as folows “that the Trustees of the Charity shall apply the income thereof in subscriptions or donations in aid of the funds of any Dispensary, Infirmary or Hospital, whether general or special upon such terms as to enable the trustees to secure the benefits of that Institution to the poor of the Borough of Launceston.” Grants are made from the rent recieved from the Lazar Ground to the Rowe Dispensary and Launceston infirmary, the South Devon and East Cornwall Hospital, the Plymouth Eye Inifirmary and the Plymouth Ear and Throat Hospital, and the Trustees receive in return tickets for the admission of patients to those institutions which are distributed by them to persons whom they may think entitled to medical assistance.

Otho Peter July 24th, 1909.

Visits: 101