.

During the 1930’s ‘The Cornish and Devon Post’ newspaper printed a series of short stories called ‘Our L’il Village’ written by ‘Sal Tregenna.’ What was unique with these stories were that they had been written in the ‘Cornish’ dialect and featured those that lived around her village.

Much of the dialect that she uses has now largely died out, although many of us still retain the ‘twang.’ For many these stories will be of hard reading as they are truly written in the broad dialect, but it is an important fact in local history that nearly all our dialect words were not Celtic, but Saxon, and are traceable in Sweet’s ‘Student’s Dictionary of Angl-Saxon.’ That means that the Saxon invaders drove the British some distance to the Westward of the Tamar. The fact that some Celtic place-names survived the invasion means only that the Saxons had no reason to alter them. Let it be understood that my spelling of them is merely phonetic; to give Sweet’s spelling of them would in many cases obscure the sound of them for local ears, but they are all to be found in his dictionary; Layt, a mill stream; lew, sheltered; heel, to cover up (potatoe plants); holm, holly; skat, to split; skode, to scatter; voach, to tread down; mawn, basket; settle, a seat; vyare, young pigs; withy, willow; eevul, a hay fork; aiglets, hawthorn berries; till, to set a trap; arrish, stubble field; linney, a shed; vitty, seemly; cloam, earthenware; cricket, a stool; barm, yeast; wug, to the right (spoken to horses); lake, a stream; mow, sheaf; mowey, rickyard; plum, soft; appledrone, wasp; stogged, stuck fast in mud; cark, to prepare horse shoes for ice; butt, a bee hive; harve, harrow (agriculture); I saw on the newspaper; I know by a bird’s nest.

The following are not traceable in Sweet but may nevertheless be Saxon words not found in extant Saxon literature: keels, skittles (compare German Kagel); trade, stuff (slightly contemptuous); wisht, melancholy; craim, to squeeze; custus, cane for punishment; glaze, to stare (occurs in Shakespeare); strub, to ravage a nest; slone, blackthorn fruit; sharps, shafts of a cart. Here are some further words which I remember; they may possibly be Celtic or Scandinavian: Skute, shoe iron; catch, a sticky mess; por, a hurry; brave, moderate; stag, male bird; squab, sort of pie.

‘Sal’ was the pen name for Millicent ‘Molly’, Mary Bartlett of Michaelstow. Born in April 1900 to John and Maude (nee Sandercock) Allen at Tresmeer Station. Her father at the time worked as a plate layer on the North Cornwall Railway line. It was whilst attending Tresmeer school that her potential writing skills were identified at the tender age of nine. The family moved to Trelaske Barton in 1910 where John farmed. By this time Molly had been joined by three brothers. The family again moved in 1913 to St. Mabyn and although she won prizes for her writing, the St. Mabyn school headmaster failed to recognise her talents. It was at the age of 14 that Molly became a school teacher, totally by accident in more ways than one. The infant school teacher at St. Mabyn had fallen off her bike, breaking her collar bone, and this led the way open for the young Molly to teach the infants. Molly continued writing and, for a period, recited monologues with a concert party which visited many towns and villages. Sharing the programme were the Padstow Orphean Quartette. She had fond memories of this time and was known as ‘Betsy Pengelly,’ the name that she used to write humorous dialect stories. It was also around this time that she introduced the pen name of ‘Sal Tregenna.’

Molly married John ‘Jack’ Bartlett at St. Mabyn in 1927 and the couple lived in a cottage at St. Tudy. Later, they moved to a cottage at Lower Tregawn and to Michaelstow Valley Nurseries, where Jack was head gardener. Their first child was born in 1932, Bryan John Allen, named after Molly’s father who was killed in a motor bike accident around the time of the baby’s birth. A second child was born 18 months later. She became involved with the WI and began writing plays for the drama section for village productions.

Molly was well renowned for her short stories and wrote for many of the Cornish newspapers and journals. Over the sixty plus years of writing her stories, Molly built up a loyal readership and her stories, especially the Christmas ones, were always well received. For a competition organised by the WI, she wrote what she thought was her best play, which was later published and performed by a well known drama group in London. The play, based on a true story in a Cornish fishing cove, won the cup for the best play. With her husband having taken employment at Trewidden gardens, the family had moved to Red Lodge, Tremetherick Cross, near Penzance, and she soon became involved with Madron WI, again writing plays for a drama section. She entered another competition with the play ‘The Storm Child,’, which was another prize winner.

In 1963, her son, Bryan died of leakemia, and a year later her daughter’s husband, Alan, also succumbed to the disease. On the golden jubilee of the WI, Molly was chosen to represent the insitute at a royal garden party at Buckingham Palace, where she was presented to the Queen for her writings, and as a member of the oldest WI in Cornwall.

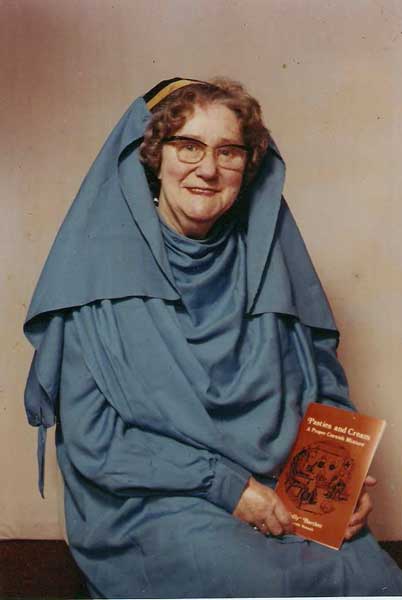

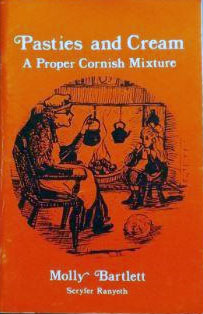

Molly (above left in 1970) was elected into the College of Bards of the Cornish Gorsedd in 1970 taking the name of ‘Scryfer Ranyeth,’ and it was with the Gorsedd that she gave a very popular concert in Launceston Town Hall in 1972 where she portrayed an old Cornish housewife tending her flu ridden husband. She wrote lyrics for folk songs with Richard Gendall for Gorsedd competitions, and won prizes. ‘Mount Misery’ was recorded by Brenda Wooton, who later sang it on Radio Cornwall in a tribute to Molly. She had her book ‘Pasties and Cream’ published in 1970 (above right) and this was followed with another in 1980 called ‘Kiddley Broth’. In 1978 she won the cup for ‘The Sweeting of the Hay.’

Soon after celebrating their celebrating their golden wedding anniversary Molly had a bad fall and became partially paralysed,. She was admitted to Barncoose Hospital. Jack who had been suffering from angina, soon after died. Due to her paralysis, she had to relearn how to write and with the help of therapy and the dedicated staff at the hospital she learnt how to type. She never returned to Red Lodge, instead moving to Trengrouse House, Helston, where she spent the rest of her life. She died peacefully at West Cornwall Hospice, Penzance on April 14th, 1988 and was cremated at Penmount Crematorium, Truro on Friday, April 22nd.

She once said, “Life holds so many memories. Some of the best can be the simplest things — a cup of tea, a chat with a neighbour, the friends who rally round when you need them, and who call for help in their turn. Shared moments with your children and the quiet hours when you could relax, or better still writ.” “Age has no terrors for me, for age is an attitude of mind. Now I have time to enjoy the simple things of life.” She did this to the very end. On her last holiday at Easter, 1988, she wrote the lyrics for a folk song to enter in the Gorsedd.

Her stories live on and bear testament to her incredible ability with the Cornish dialect. Some of these stories have now been transcribed for the site, so sit back and enjoy a ‘viddy’ way of speaking in Cornwall! Thank you Molly.

Dictionary of Cornish words and phrases.

Visits: 348