From an edited transcription of an 1956 article.

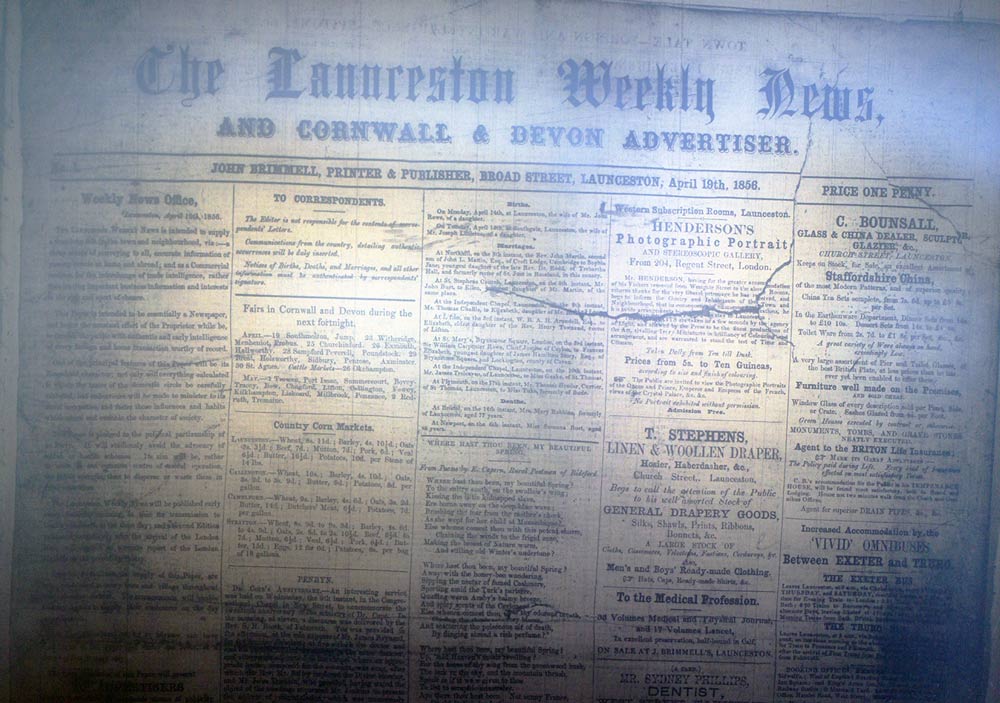

John Brimmell of Broad Street, Launceston on April 19th, 1856, ran the first print of ‘The Launceston Weekly News and Cornwall and Devon Advertiser.’ This was not the town’s first newspaper, but it was the first successful one. The first ever paper for Launceston was ‘The Launceston Journal,’ published on Tuesday, January 26th, 1784, according to the tenor of the Bye-Laws of the Corporation from the Press of H. Lawrence under the sanction of a worthy Patriot of unblemished Character. This, however, was in fact a sham newspaper, one issue only, composed simply of ‘burlesque’ intelligence and personal attacks on local figures. Another Newspaper, ‘The Reformer,’ (below) was printed by Thomas Eyre and produced for the hard fought election of 1832, revolving around the agitation for the great Reform Bill of that year. A week after ‘The Reformer’ appeared the Tories published their rival, ‘The Guardian,’ printed by the brothers Theodore and William Roe Bray. These two weekly papers were small in content and were published to publicise the personalities of the election campaign and were generally no more than election propaganda. The contest which, incidentally, ended with the defeat, by seven votes, of the Liberal candidate, David Howell, by the Duke of Northumberland’s nominee, Sir Henry Hardinge. Once the election was completed both the fledgling papers were closed.

The first actual newspaper was ‘The Launceston Examiner,’ published by Thomas William Maddox, which appeared weekly for about six months in 1844. This was a four page sheet, of small sized pages. Its failure was due to the fact that it followed the practise of so many other country newspapers of that time in that the main content was of foreign intelligence and Court and London news, with a few scattered pieces of local news.

So it was to be another twelve years before Launceston had its own local newspaper. Even then though its reach was only into the homes of the landed gentry and clergy for the balance of the districts population was largely illiterate, and in the lower echelons of what was a very carefully stratified society, that inability to read or write was almost universal. But the repeal of the Stamp Act, an infamous ‘Tax of Knowledge,’ which had rendered the purchase of a newspaper prohibitive to any other than the rich, and the improvement in education paved the way for a wider readership. The shopkeepers and traders of Launceston were prospering sufficiently to send their children to school, even at the payment of some pence per week which was a substantial sum in those days when a labourers wage for a week was only a few schillings. The National School had been opened in 1841, and there were other educational establishments predominantly of a private nature setting up. There was an awakening in the public with interest in the affairs of the day particularly in the Reform Movement that was eventually to bring about the universal franchise, compulsory education and all the other things we take for granted today.

It was a time that Britain was in the throes of her first war since Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, with the Crimean War. The public conscience was awakening and its interest in such matters was a boon to a fledgling newspaper. At the time the Newspaper Society proudly stated “The local newspaper is the lifeblood of the community.”

In 1856, the townspeople were most certainly in the dark as to borough affairs, with meetings often held behind closed doors and word of mouth campaigns the only opposition which could be raised to selfish measures. The Member of Parliament was virtually chosen by one man (The Duke of Northumberland) and the town police force consisted of one constable (employed by the Town Council), if harsh to the poor then respectful to his betters; with the policy of might (or money) being right generally enforced if no longer timidly accepted. So it was to this scene at a cost of 1d. per copy that ‘The Launceston Weekly News and Cornwall and Devon Advertiser’ made its appearance.

An early sensation was the murder of an old man at Langore. Roger Drew, who carried on the business as a carpenter as well as running a small grocers shop, and who lived alone, was found as the paper put it at the time, “weltering in his blood” one Sunday morning by a villager going to buy sweets. Apprehended almost immediately was a 30 year old ex-Marine, John Doidge who was subsequently charged and found guilty of the murder. His execution at Bodmin Gaol was the last to be held publicly.

Life was hard in its lesser occasions, too, a master, not satisfied with the way in which his youthful employees were working, could have them sent to prison and whipped for being ‘idle and disorderly apprentices.’ Another report from the same time detailed the diet of the time; Meat twice a week; the other days, rice and treacle; dry bread and milk and water in the mornings and evenings. This was also the time when the ‘buildings’, tenements that were to be labelled as slum property were being erected, not by speculative developers, but by philanthropic organisations, with hundreds of applications pouring in to rent them, an indication of what previous housing conditions were like.

The first local case of any importance reported was indicative of the savage punishment handed out at that time was the prosecution of a 19 year old labourer for killing a sheep belonging to a tenant of Squire Lethbridge at Tregeare. Sent for trial at Bodmin assizes and there found guilty, the youth was sentenced to 15 years transportation.

The paper was originally published as a four page sheet, the front page being given over to local news and advertisements, and the remaining three being of national and international news. In fact, those three pages would have been printed, probably in London, before the papers arrived in Launceston; it then remained for the local publisher to set up his type, print the blank front page with local matter, and issue his paper. That first front page contained but little local news; nearly a column was given over to a poem about spring by E. Capern, Rural Postman, of Bideford, and to anecdotes. A report of a Congregational anniversary at Penryn; a report of the Parliamentary Committee’s deliberations on the Adulteration of Food Bill. There were two columns of advertisements, largely of John Brimmell’s own wares such as stationary, school-books, printing, bookbinding,paper hangings, and all the many and varied types of goods which each tradesman seemed to stock in those days. Another advertiser, a C. Bounsall, of Church Street, Launceston, was not only a glass and china dealer, sculptor and glazier; but also made furniture on the premises, erected greenhouses, kept a nice line in tombstones and was an insurance agent. Besides this, his advertisement in that issue pointed out, the board and lodging to be had at his temperance hotel was most satisfactory and only two minutes walk from the coach and omnibus offices. To make sure his net was spread wide enough, he added in a postscript to his advertisement that he was also ‘Agent for superior Drain Pipes, etc., etc.’

The early issue had the following tradesmen mentioned; T. Stephens, draper of Church Street, Mr. Langdon,of the Northumberland Foundry, St. Thomas, W. Coad, draper of High Street, J. Hodge and Son and Messrs James and Ball, coaching and posting contractors, R. Robbins, of the Golden Boot, Broad Street, J. Phillips, baker and refreshment house proprietor, opposite the White Hart Hotel in Broad Street (Now the betting shop), John Dawe, auctioneer of Lewannick, and J. Geake, travel and insurance agent, of St. Thomas.

John Brimmell soon found competition. He had started, as he recorded in the first issue, ‘a newspaper…pledged to the political partizanship of no party. But within eleven months, either from political or business rivalry, his competitor, the ancestor of ‘The Cornish and Devon Post,’ had made its appearance. That was in March, 1857, and it was very clear that the two papers were in opposite camps politically. John Brimmell was the Conservative and his rival on the Liberal side.

The rival began its life as a supplement to ‘The Cornish Times’ which was also priced at 1d. with it being published and printed by E. Philp of Callington and J. Philp of Liskeard. It made its first appearance on January 3rd, 1857 and it soon had a circulation of nearly 1,200 weekly, and in March of 1857 (coinciding with the dissolution of Parliament, an indication of the mainly political role played by papers in those days) it extended to Launceston, with a third brother, William Philp of Broad Street, Launceston, publishing a single sheet printed on one side only and headed ‘Supplement to the Cornish Times.’ The three brothers were soon claiming a circulation of upwards of 1,500 weekly. At the next Dissolution of Parliament, in May, 1859, the supplement developed into an independent paper as ‘The East Cornwall Times,’ this independence did not refer to its politics, however, as it remained with its sister paper as a staunch supporter of the Liberal cause.

William Philp had been apprenticed to the aforementioned Launceston printer Thomas Eyre, serving his indentures of seven years before working in London for two years. He returned to Launceston in 1831 and went into business as a printer in Westgate Street, subsequently moving to Broad Street and it is here that he published his Supplement and eventually the ‘East Cornwall Times.’ With the aid of two apprentices (George Robbins, who would go on to have a distinguished journalistic career in London, being one of them) he did all the reporting, editing, setting of type and printing of the paper, which was produced on an old fashioned, even for those days, Eagle press in the cellar of what is now Webbers Estate Agents in the Square.

The political nature of each of the two Launceston papers was taken very seriously in those days, for politics were very much of local application and not confined to national affairs. The Town Council elections were fought along party lines, and practically every local issue saw the Conservatives lined up on one side and the Liberals on the other. William Philp, in those early days, fought many a battle for freedom in his columns, as indeed did John Brimmell in his paper, although each was careful never to support the other. William Philp’s greatest achievement was his success in securing the admission of a press representitive to the meetings of the Town Council in 1861, which was a feat in itself when the victory was won against someone such as the then almost all-powerful Town Clerk, Mr. Charles Gurney.

Over a decade the battle raged between the entrenched champions of the old way of life, with privilege rampant, and the newer adherents of a wider franchise, bearing the sneering title of Radicals as a badge of honour. Mr. Richard Peter, was the principal opponent of Charles Gurney; elected a Town Councillor, he refused for a year or more to attend any meetings because he was summoned to them by a printed notice bearing the printed signature of the Town Clerk. He won his point in the end, and that was the thin end of the wedge, with Charles Gurney eventually being ousted and Richard Peter himself eventually becoming Town Clerk, to face in his turn a campaign of abuse and attack from his political enemies. But an important principle had been established: that the Town Clerk was the servant of the Council and not its master, and from those forgotten battles of nearly 150 years ago stem the freedom to conduct our own affairs, free from any form of despotism, benevolent or otherwise, that we enjoy today. Richard Peter was to become a frequent contributor to both papers in those early days, while Richard Robbins was another prolific writer on local affairs, followed in this by his son Alfred Robbins.

So the respective papers continued their stormy ways, but a chance was to come in 1877 and a more familiar name makes its first appearance. In December of that year ‘The East Cornwall Times’ issued its last number, and the Phoenix that arose from its ashes was ‘The Cornish and Devon Post.’ That incorporated ‘The East Cornwall Times’ and the change in title was to suit the wider role it was intended to play, for it began to circulate not only in Launceston, but in Callington, Camelford, Boscastle, Bude, Stratton, Holsworthy, Okehampton, Lifton and to quote its early masthead, ‘etc.,’ which covered the villages and hamlets of the wide area of North Cornwall and West Devon.

The first issue of the new publication was, according to its imprint, ‘printed and published by W. L. Powell for the proprietors, W. S. Cater and Co., At their Machine Printing works, Westgate Street, Launceston, in the parish of Saint Mary Magdalene, in the Borough of Dunheved, otherwise Launceston, in the County of Cornwall.’ Astute enough to see their opportunity and to plan accordingly, the producers of the new paper, which as they had hoped, ‘sold like hot cakes,’ were able to announce with pride ‘arrangements are completed for printing the paper by Steam Power.’ Prior to that, the machine was turned by relays of men! With eight pages and still priced at 1d. it still gave plenty of national and international news. William Smale Cater, the proprietor, was Launceston born of a Launceston family, and was educated at Horwell Grammar School. In early life he sought his fortune in London, and was for some years employed with a London firm of publishers. He returned to Launceston and engaged in the printing business with a Mr. Eveleigh, taking over the business in Westgate Street which had been conducted by Messrs. Cory. But although he did bring about the first publication of ‘The Cornish and Devon,’ it was not long before he severed his connection with the paper, and in 1883 he established a business in Church Street and also a printing business in Race Hill, from which he produced ‘The Penny Marvel,’ an annual publication which was well worthy of its title apparently. William Smale Cater has another claim to fame as at the age of 18, he, with Dr. Wise and another local man, was the first to ride out of Launceston on a penny-farthing bicycle.

William Lydra Powell, as mentioned above, was associated with the birth of ‘The Cornish and Devon Post,’ and he soon became its proprietor as well as its editor. His was a journalistic career, born at Exeter, he started on ‘The Devon Weekly Times’ moved later to ‘The Torquay Times’ and later to ‘The North Devon Journal’ at Barnstaple. Then he became associated with the National Press Agency, London, and subsequently started papers in the Home Counties. It was from ‘The Mid-Surrey Times’ at Richmond that he came to Launceston, and was instrumental in converting the purely local ‘East Cornwall Times’ into the wider sphere of ‘The Cornish and Devon’ building it eventually into what he called ‘A Newspaper Circle’; with separate ‘Posts’ for the different towns and areas. His was the age of expansion for ‘The Cornish and Devon’, he published not only the ‘Bude and Stratton Post,’ ‘Holsworthy Post,’ ‘Callington Post,’ ‘Camelford and Delabole Post,’ ‘Okehampton Post’ and ‘Wadebridge Post,’ but also the ‘Bodmin Post’ and the ‘Padstow Post.’

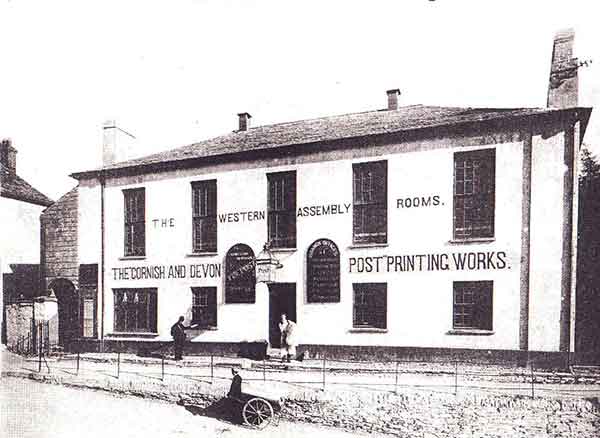

William Lydra Powell found time, too, to fight and win the battle for the narrow gauge railway in North Cornwall; he sat for nine years on the Town Council; he wrote various guide-books and directories; he campaigned vigorously for his beloved Liberal Party. The papers prospered under his expert leadership, and growing, it was necessary for larger premises and so in 1895 the papers were moved to the more commodious building in what was then Western Road and also called the Western Assembly rooms (below). New machinery was installed for the purpose of more expeditious production.

William Lydra Powell died in April, 1904, at his home, Devonia, Dunheved Road, at the early age of 51. His eight paged paper, still only 1d. and now containing local news on all pages, was produced for the interim period on behalf of his widow and executors, and then was acquired by a man that was to become an integral apart of the town, Charles Orchard Sharp (below).

In his first editorial, July 23rd, 1904, when, to cast a glance at the contemporary scene, the Launceston Horse Show was striving to survive the disaster of a thunderstorm which had cut its attendance, and General Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army, was including Launceston in his triumphal itinerary, Orchard Sharp told his new readers that “no pains will be spared to supply an interesting variety of local news, as well as a careful summary of general intelligence; and, further, it is promised that comment, however searching as to principles, will never be bitter as to persons.” And, he added, “it is hoped to fulfil the law of Christian charity even in the political sphere,” going on to declare stoutly: “This is a Liberal journal, which will appeal to Liberalism with backbone in it.”

Charles Orchard Sharp had already achieved a distinguished journalistic career in Fleet Street when he came to Launceston: he had become Assistant Editor of ‘The Daily Chronicle’. He was a Fellow of the Institute of Journalists, and maintained an exceedingly high standard of editorial ability. Fair and just in his comments, he was respected alike by his political friends and opponents. He was a great Baptist, holding many lay offices, and a local preacher of eloquence and conviction. Until his death in 1942, he retained undimmed his vital interest in the affairs of his adopted town and district, and his great worry in his final illness was his inability to write his usual leaders. In 1908, Charles Sharp took into partnership Mr. Glanville H. Scantlebury, who came from a Launceston family, with connections at Stoke Climsland. Glanville was a young man who had served his journalistic apprenticeship on ‘The Post’ in the days of Powell and after gaining further experience in London, returned to the paper. He became its editor, with Charles Sharp becoming a ‘sleeping partner,’ and in fact moving to Plymouth as Assistant Editor of ‘The Western Daily Mercury.’ In 1912 Glanville Scantlebury died at the tragically early age of 28, leaving a widow and three young children. He too played his part in the life of the community, in addition to his vital role as editor, and was widely mourned.

It was then that Charles Sharp relinquished his post at Plymouth to return to Launceston and again take over the editorship of his paper. At this time (1913), he formed a private company, taking into partnership Maurice Prout (below left) and Arthur Bray Venning (below right), two young Launceston men who had already been with the paper from the days of William Lydra Powell. Under his guidance and with their energetic and able support, the paper flourished even more, surmounting the difficulties of the 1914-18 war period and going on to even greater triumphs in the post war years.

Cornish and Devon Post, Saturday, September 26th, 1914

Launceston Weekly News, Saturday, September 8th, 1917

Launceston Weekly News, Saturday, September 15th, 1917

Launceston Weekly News, Saturday, August 31st, 1918

AMALGAMATION

All this time, ‘The Launceston Weekly News’ had contained as a family business, with John Brimmell being succeeded by his sons, A. W. D. Brimmell and S. D. Brimmell, both gifted journalists. From the original Broad Street of the early days, it had shifted its headquarters to Church Street opposite the Church. It had carved out a place for itself in the hearts of Launcestonians especially, but progress brings change and in 1931 it was acquired by the larger ‘Cornish and Devon Post,’ to become a part of the newspaper circle extending so far beyond the borough boundaries of Launceston and so much a part of the weekly life of thousands of people in both Devon and Cornwall. That amalgamation came with the first issue of the joint ‘Post and Weekly News’ on July 4th, 1931, when, to take another look at the contemporary scene, the ‘Talkies’ were superseding silent films at Launceston; when the old established Dunheved College and Horwell Grammar School for Boys had reached the end of their careers, and Mr. Henry Spencer Toy had just been named as the first headmaster of the new Launceston College which was to succeed them. In the first joint editorial, tribute was paid to the great days of the past, but the change was hailed as a further sign of progress. And in its new role as the sole organ of the town and district, the flag of political allegiance was hauled down, with ‘The Post and Weekly News’ pledging itself to a policy of independence, to represent, as it stated, all parties, by being ‘conducted along lines philosophical rather than polemical.’ That leader went on to state the paper’s line, still maintained to this day. “We shall not be unmindful of the editorial responsibility to be fair all round, not by excluding political discussion, but by giving every reasonable point of view a fair show. The editor will seek to be an interpreter rather than an advocate.”

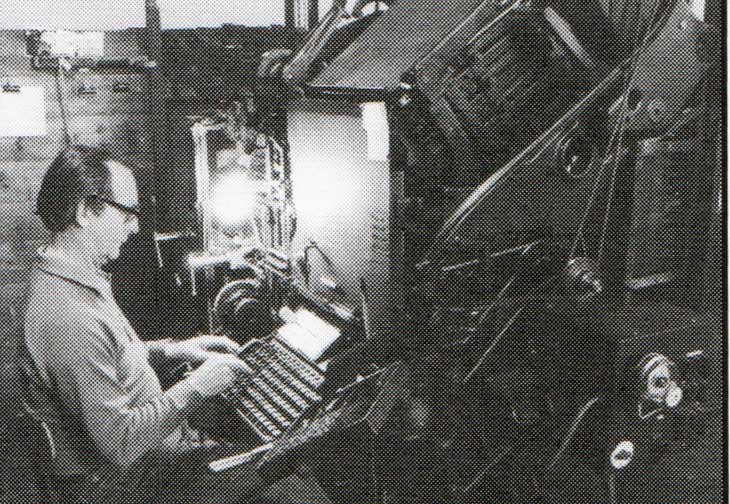

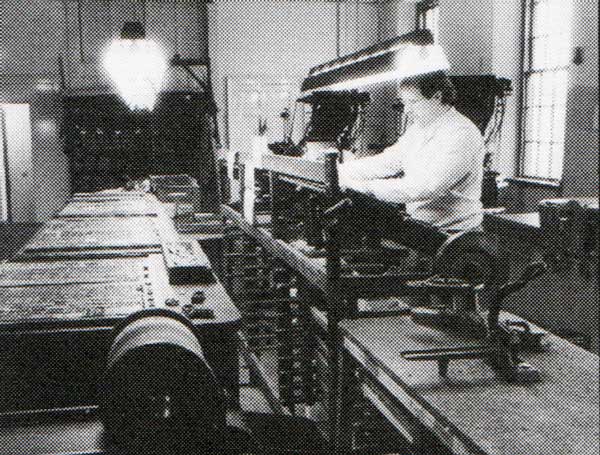

The union proved a successful one and although World War Two proved difficult with paper and labour shortages along with difficulties in securing machinery replacements, the paper continued to be produced on a weekly basis. In 1955 the installation of a Cossar press (seen below working with Jack Uren collecting the printed Newspapers in 1985) at a cost of £10,000, provided the paper with up to date printing equipment well before many other provincial papers in the country. The paper was also the first in Cornwall to introduce the Linotype, which brought mechanisation into type setting instead of the laborious former method of picking out each character by hand.

The death of Charles Orchard Sharp in 1942 was a great blow for the paper, but in Maurice Prout, there proved to be an ideal replacement. In fact Maurice for many years had been shouldering the major burden of occupying the editorial chair, maintaining the high standards established by his distinguished predecessors down the years and in conjunction with his partner, Arthur Bray Venning, who directed the advertising side, continued to run the paper successfully. Maurice passed away in 1961 and Arthur in 1968.

Later Geoff Seccombe became editor with Adrian Ruck his deputy.

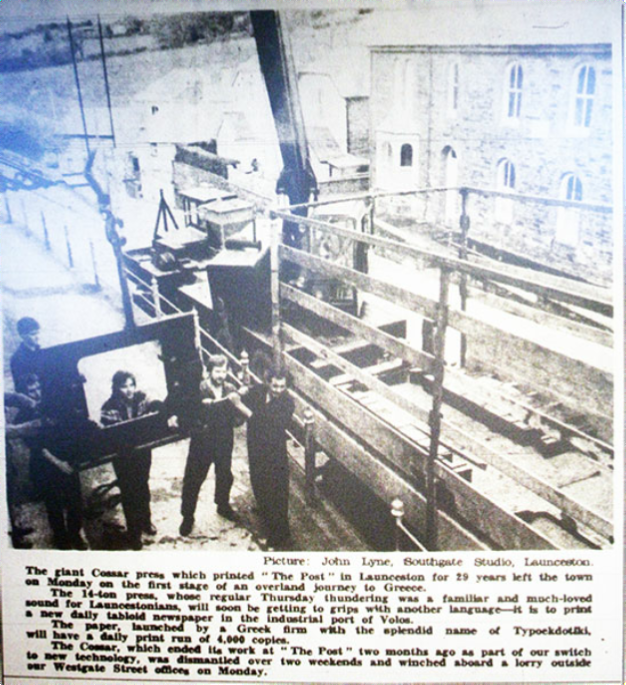

In 1985 the paper installed a new web offset press which enabled a print of more than the 12 page limit of the Cossar press (seen being removed below left). The following year ‘The Cornish & Devon Post’ came into the ownership of Tindle Newspapers and a new era for the series began and which continues to this day.

Cornish and Devon Post, Saturday May 26th, 1951

Visits: 245