I was born on October 11th 1910 at Tamar Town, North Petherwin, which is near the town of Launceston. Within a few months my parents moved to Larrick, so apart from being taken there to visit grandma Earle, I don’t remember the area. I cannot recollect a clear picture of Larrick, but I do know it was a small cottage with a garden and my sister Millie was born there, also that she fell into a rose bush and lost an eye; my Father was away in Canada at the time, and this tragedy hastened him home.

Our next home was Bottonett cottage: I recall Father moving the furniture there with two horses and a farm wagon. At Bottonett I began to understand things, it was a nice three-bedroom farm cottage with a large garden and half an acre of land. Father was employed by the Cole Brothers and later by Mr Treize. The cottage conveniences were – a bucket outside lavatory, an open fire place approx 5ft wide with crooks to hang kettles, an oven built into the wall for baking, and a three-legged brandess to rest the frying pan on. The floor consisted of large square slate stone tiles, and our only fuel was wood cut from the farm hedges. It was common practice for the farm worker to cut down the wood and have it for free – providing they repaired the hedges. Washing water was from rain water tank and drinking water was fetched by bucket from a spring in a wood 500 yards away down a steep slippery path. For washing you had to heat the water from the kettles, pour it into a wood container and rub it for hours; to bath we used the same wood container, bathing one after the other. For lighting we used oil lamps, candles and a hurricane lantern.

The cottage was situated approx 5 miles from Launceston, 2 from Trebullett and 3 from Trekenner School. Trebullett was our local village where there was a Post Office a General Shop a Cobbler’s Shop, a Carpenter’s Shop and a Blacksmith’s Shop. It was a quaint old village with a deep well supplying the inhabitancy with water. It also had a Chapel, a Cemetery and a Sunday school, which dated back to 1700. Fields encircled the cottage and to reach the parish roads you had to cross three fields. We spent 12 years at Bottonett where Ivy, Frank, Lizzie, Mabel and Dorothy were born (Frank being adopted by grandma Mullus who lived just outside Trebullett with her husband & two grown up sons, Frank was very lucky to find himself living in luxury) the remainder of us lived in poverty although we were content and happy together.Our parents worked themselves to the bone to feed us making full use of the garden and plot to provide vegetables, keeping hens for eggs and a pig for meat. The pig meat was kept in a salted wooden container and then removed, put in cloth bags and hung to the ceiling and used as necessary. We were able to get plenty of rabbits: Father used to trap them and Mother made lovely pies, pasties, and even fried them. We got our flour from the local flour mill at Ruses Mill, owned by the Jasper family, collected in a white pillow slip, 14 lbs at a time (this became my job in later years); it was the first time I met the Jasper family, there were eight of them, seven girls and one boy, in spite of this they were well off in comparison to us, Mrs Jasper would give me toys that her family had outgrown to take home for my sisters, (as events turned out in 1934 I married Elsie, one of the daughters).

At the back of the cottage there was an orchard we were allowed to pick and hoard enough apples to last for months. I recall there was a wasp nest in the orchard and not knowing better I once had a stick and pushed it in the nest: I got badly stung; in fact I required medical treatment. However, in this period people used medical remedies such as putting a cube of blue in a cloth bag and dressing the stings (originally put in the washing water to whiten clothes) many such remedies were used, table salt for sore throats, vinegar to reduce swellings, a cup of farm cider heated with a hot poker for a cold and many more, these remedies having been handed down from generation to generation. My Father was earning about 25 shillings a week and my Mother also did washing to subsidise the income, but it was a never-ending struggle with so many to feed and clothe. Our clothes consisted of what people gave us, so we were very excited to get parcels of clothes. Of course at that time perhaps the Squire was wealthy and lived at Landue with two sisters; they did a lot of organizing in Lezant Parish including visiting the very poor. The farmers also found it difficult in finding weekly wages to pay their men.

Although life was simple, we had our moments of pleasure – especially at Christmas time. As children, we got excited hanging up our stockings and then showing each other the contents. We enjoyed a special lunch including a Christmas pudding, some sweets and shared a bag of oranges. We would sit a round a log fire and sing carols, then during the afternoon a few people from the village would call and give us presents; some times the Methodist Minister would call and say a prayer for us. We certainly enjoyed our Xmas celebrations. I also recall other Christmases I spent away from home: in Malta, Capetown, Hong Kong. Memorable were ones spent during the 2nt World war: one patrolling the seas between Iceland and Green Land – as I walked between the decks the loud speakers were blasting out “Dreaming of a white Xmas” to the background sound of ice grinding against the ship’s side; as I went on the upper deck the daylight was almost blanked out by a heavy snow storm. Also when we docked in Newcastle for Christmas, and Elsie decided to come up from Cornwall to spend it with me: this was a tremendous undertaking with our two small children. Fortunately a friend accompanied her to Crewe and I came down to Crewe to meet her. When we met, I discovered her large tin trunk containing the necessary clothes – but the oven ready turkey had not been loaded at Plymouth: luckily we got it the following day, and enjoyed the meal with our land lady and husband, who were lovely people. We enjoyed our special Christmas together that year, but it became overshadowed by worry over our young children’s health: Christine became ill with suspected diptheria and was taken away in a horse drawn ambulance; luckily she did not have diptheria and was allowed home, but in the mean time Dorothy became ill with convulsions! Fortunately both the illnesses resolved and the children recovered sufficiently to travel home: this time I was able to accompany them, as I was given a few days leave.

When I was five I realised there was a terrible war on: I remember an Army truck visiting Trebullett with several bandsmen playing patriotic songs (Land of hope and Glory etc) trying to entice men to join the forces. There were also local ‘big shots’ riding around on horseback to the farms persuading farmers to release their sons or labourers (and dodging the issue themselves). The War Office was particularly keen to recruit experienced horsemen to work in the battlefields hauling the guns and took all the best horses from the farms; I remember Harry Cole volunteered and I walked with Miss Cole to the railway station to see him off. Men of all ages were taken off the farms and were slaughtered in thousands. They were replaced by the Women’s Land Army. I particularly remember when the farmer hired the large traction engine and threshing machines to thresh the huge stacks of corn, about twenty land army women would come to assist, I would be there running around and they would pick me up and hug me, and I was frightened of them. I also remember seeing a reconnaissance Zeppelin plane – there were two built (known as R1 and R2) but both later crashed; I remember how frightened I was to see this huge thing overhead – I thought the Germans had arrived.

Also in this period there was a severe epidemic of Influenza and again thousands died; no households escaped it, and in some cases it cleared the complete family. We all got it, fortunately we survived but our chickens starved to death as we all were too ill and weak to attend to them. I do not remember the doctor calling except on that occasion. The district nurse attended to all our illnesses including the home births of all the family. On occasions if we got toothache and if Father was unable to extract it, we had to walk 5 miles to Launceston for dental treatment’. There were three prices: ‘straight out’ a bob, injection five bob, gas ten bob – ours was always a bob touch!

My sisters and I attended Trekenner School from Bottonett. Crossing the fields and getting to Trekenner was an achievement by itself in all weathers – especially with ill-equipped footwear and no weatherproof clothing The CC School was served by Head Master Mr Edwards, Miss Maddever and Miss Dennis. They were excellent teachers, and inspired us to work hard in order to achieve good starts in life: Lizzie went on to become a head teacher, Mabel a nursing sister, and Frank a prison warder. We took a sandwich or a pasty for lunch (made warm in a coal stove by the junior teacher) and a can of cold water was placed on the playground wall to drink. The toilets were of the bucket type, and under the supervision of the Head Master the senior boys had to dig pits and empty the buckets!

My career was based on learning to be a skilled farm worker: regretfully on leaving school my academic qualifications were very poor. Nevertheless, I spent all my spare time understudying my Father, and in doing this I could earn a few shillings as well as prepare for farm employment. In spite of my lack of interest, Mr Edwards was well conversed with our poor circumstances and always invited all of us to his daughter’s Birthday Party, really we had never seen such a spread and variety of food and I will never forget his generosity and his letters in the second world war. The war years passed by, with us remaining at Bottonett. I was eight when Harry returned – still the same kind generous man as before, but shell shocked and suffering from the after effects of gas. His health deteriorated so much so that shortly afterwards my Father found him dead. Really this was terrible: we would miss the little luxuries he frequently handed to us, and we were extremely sad. Harry was buried at Trebullett.

By 1918, some of us were regularly going to Chapel and Sunday School (where Father was a teacher); even Trebullett was hazardous to reach across the fields. Father was given all Harry’s clothes: we had never seen him look so smart on Sundays! There was a more pleasant side to Sunday School every alternate year, trips were arranged to the seaside! A farm wagon would be fitted with seats by the village carpenter the day before the trip, then early next morning two horses and driver would arrive followed by the Sunday School teachers and children. We were driven to Launceston, where we boarded a three-horse Charabanc to Halwell Railway Junction, then it was by train to Bude. We spent several hours on the beach enjoying our first glimpse of the sea, and were given food, drink and sweets before returning home in the same fashion. A special Sunday School event was held annually: we had to do a period of weekly practices. A platform was rigged up in the Chapel, and on a Sunday all the children dressed in their best clothes and sang to the audience; this was followed by a repeat on the following Tuesday with sports in a local field, (now the best bit) a tea in the Sunday School Room, and we were given what was left over to take home for the younger children. Another event was named ‘Band of Hope’ and was held either at Trebullett, Landue, Carthamartha (with farm wagon transport arranged). A band was hired, there were sports, and yes…a tea! This was organized by the ‘Circuit’ (a group of local chapels); its main aim was to emphasise the evils of alcoholism – I think this had a future influence on the children.

After about the age of eight, Father considered “a little less play and more work will make Jack a better boy” so he decided to allot me jobs to do after school – such as a pile of trees to be sawn for the open fire, and a portion of the garden to be forked in readiness for him to till after work. He also had visions of me earning a few bob on the farm – especially in the school holidays. There were many jobs I could do, and the farmer was glad to employ a nimble youngster as several of his helpers were crippled old men in their seventies! The attractive thing about working in the harvest field was that the farmer’s wife supplied afternoon teas consisting of lovely cream-filled apple pasties, and also provided harvest suppers. I gradually became fascinated with the farm. It was about this time that Father taught me how to catch moles: at first I only had a couple of traps but this eventually grew to a dozen. Once the moles were caught, we skinned them and nailed the skins onto boards to dry; when they totalled about twenty, we sent the skins to a company and received about four pence a skin (old money) – quite a little earner! The skins were used to make expensive ladies coats. I also dried rabbit skins, which I sold to a man who came around shouting “Rags Bones and Rabbit Skins”. I under-studied my Father every opportunity I could: the experience was invaluable when I began working on a farm. However, my interest in school just became a compulsory nuisance, and as the future is not ours to see – I did not realize the value of education except perhaps for arithmetic (which I seem to have had a flare for, but otherwise lessons were a waste of time for me.)

My sisters interested themselves putting pieces of slate in the hedge and oddments on the slates pretending to be a shop keeper, also picking wild flowers and decorating a portion of the hedge in addition to understudying Mother and doing house hold tasks; they did have a few rag dolls to play with and a very old type of gramophone. They also spent time learning to sew – especially making rag dolls – some were quite large and they use to take them to bed with them and get many hours of pleasure wheeling them around in an old pram!

Time like an ever rolling stream went by: we became even more worse off because as we grew our requirements increased and we required more food etc. Never the less, we had become accustomed to small mercies and were content to have enough to eat: we were jolly and happy together. Troubled times came when the Coles sold the farm: Father found employment with a Mr Treize (an old man with a son and daughter). We soon discovered that they were ‘big shots’ and we were the ‘scruff of the earth’ more so the old man. We missed the kindness and generosity of the Coles; I was not welcome on the farm. The Treize’s had learnt to run before they could walk – they soon became short of money and could not pay the wages. Just imagine our predicament, with no money to buy food at the shop. You would never believe old man Triese’s behaviour though: he would instruct my Dad to harness the pony into the rubber tyre gingle, back it to his door and appear dressed in a long tailed coat wearing a cape and high top hat! After a few months he went bankrupt.

Father then found a job with Mr Hilson of Trecarrell. We moved to Trebullett, a three room cob-built cottage that he owned, with a garden quite near the village. It was almost completely lacking in conveniences: we had to fetch all our water from the village well. The advantage though was that it was much nearer school. The cottage was joining the parish road so some times the Vicar travelling in his donkey and trap visited us. We settled at Trebullett, Father walking daily to Trecarrell approximately one mile away. During this period I felt lost – it was only occasionally that I visited the farm; but I soon found evening and Saturday work nearby at Trenute farm, and on Sundays I blew the Chapel organ. I think it was at Trebullett that Tommy was born, more the merrier.

Nothing too eventful occurred while we were at Trebullett. We stayed there for five years, before moving to White Lodge at Larrick. This was a three-bedroom cottage owned by Mr Dawe; Father worked part-time for him and Mr Jasper of Ruses Mill. The cottage was blessed with its own well for water, and a coal-burning cooker. The disadvantage though was that it was three miles from school! We had a large garden so I spent my spare time working in the garden, and then doing odd jobs at Ruses Mill.

I was approaching 14 years of age – the crucial time for leaving school finding a job what I would like to have done was to learn carpentry but you were required to pay 7 shillings and 6 pence per week apprentice fee, with our low family income, this was unthinkable, so I found work at Ruses Mill with Mr Jasper who owned a farm and a corn mill. It was a tradition that single farm workers lived in the farmhouse where they worked (always on call), but in my case this was not possible because of Mr Jasper’s large family. However, in due course I occupied a room in a derelict cottage nearby and had my meals with the family the cottage was used by Mrs Jasper for all her baking as it had a coal burning stove which kept the place warm. I was nervous there at first: being almost joining the mill – rats used to rattle over the ceiling during the night! At the cottage I was supplied with a pan and soap etc to wash. If I went home and returned late, I had a key to get in, and would find a cup of milk and some biscuits inside the door! My ‘alarm-clock’ each morning was a loud knock on the door!

I was really lucky for clothes: work-wise, Aunt Jane gave me her brother’s army uniforms and two pairs of boots from the First World War (the best I had looked for a while!). I began work delivering the goods from the mill to the farms in the areas of Lezant, North Hill, and South Petherwin with a horse and trap. I had a time to start but not to finish, and I was often on the road late at night the trap being fitted with candle lanterns. This was my qualifying period I was soon to be conveying maize, barley, bran coal etc with two horses and a wagon from Kelly Bray Railway Station; here I had to compete with much older wise men drawing ochre from Coad’s Green. This meant a 6 am start, with two journeys to Kelly Bray (6 miles each way): I had to shovel off 4 tons of ochre into a truck, together with two returning loads to unload at Ruses Mill. Coming down the very steep hill with a 2 ton load was a nightmare – only a few years previously a Mr White was killed by a wagon getting out of control. My shaft horse was a large grey mare: she was a biter, and at first I was scared of her, but as time went by she would only chase and bite other people, not me. She knew every inch of that dangerous hill, so I just walked be side her and she did the navigating. I did have a few frightening incidents: once when Mr Jasper was assisting me with a heavy laden trap-load of deliveries with an additional front horse, the chains to the trap broke part way up the hill – resulting in the trap running back, over-turning and becoming severely damaged. There were many other miner scares with the harness breaking in the hills (all for 1 shilling a day and plenty of good food). In addition I worked on the farm owned by my employer, and often drove my employer’s children to school in a rubber tyre pony jingle when the weather was too bad for them to cycle (the jingle being fitted with a large umbrella!). The oldest children went to Launceston Grammar School, while the younger ones attended school at Trekenner. I also spent time repairing bicycles, and occasionally when my employer and his wife went out together to attend perhaps a funeral I looked after the smaller children not yet going to school, I did not have any transport of my own to get about with, so Mr Jasper gave me a bike that used to belong to his daughter: it was one that she had crashed into the bridge and broken the frame (very dangerous!) – but I tied it up and used it.

I felt confident carrying out the work at Ruses Mill: I was content and for a hired worker I received very generous treatment. But it is difficult to explain the inferiority complex experienced by being employed individually – particularly so if you are living on the premises. Without any thought of class distinction on the part of my employer, there were times when guests were being entertained or parties being held when I had to make myself scarce; it was accepted by all employees that the employers were ‘little gods’ – even to the extent of taking advantage of their privileged education to brain wash their employees on politics at voting times!

I did meet up with other young farm workers in the village and enjoyed a bit of a laugh and organized a few bicycle trips. One day when we were all off together, we cycled to Tavistock Goose Fair. I joined one of the lads in the boat swings and became rather ill: I got out and was green and sick – a woman near by said “Fancy a young boy like that being so drunk!” On the way home (well after midnight) two of us became detached and got lost; by the time we arrived back they had sent out search parties! In this period there was a Government Scheme to enable farm workers to immigrate to Canada. I applied, passed the medical and was accepted but unfortunately I did not have the £10 fee required. At that time I was earning just 5s. a week, and in spite of every effort I could not borrow £10, so I missed what even Father thought was a golden opportunity. I knew some older men that had immigrated to Canada and after a few years came back with enough money to set up in farming themselves!

Now its approaching March 1926.the month when farm workers re view their work schedule for the following year, both my Father and I decided the lifting and carrying of 2 cwt sacks of corn was detrimental health wise so sad it may be for Mr Jasper and all the long hours I am off to a new start. The end of my first work epic. I got a job as a horseman at Lower Penrest – I joined Mr Goodman’s household and settled down to the work schedule making the acquaintance of Mr Lansallas a workman. Mr Lansallas was some what superior – a war veteran very jolly, care free and extremely helpful. He believed on making the most of life, put your troubles in your old kit bag and smile was his motto and he proved to be a second Father to me. I never quite understood what made him so different from other farm workers. The boss was polite to him, the people in the parish respected him – he did own his own house and I suspect that he distinguished himself in the war because even the Squire travelling in his four-wheel two horse coach with a top hat and a uniformed coachman, would stop and speak to him. At school we were taught to lift our hat to the Squire!

I managed the horse work not with out a number of little incidences nothing to worry about. The routine now is working on the land not on the roads but occasionally goods had to be collected with horses and wagon from Launceston, on one trip I collected building material from the saw mill it was loaded by crane and very heavy, I had difficult getting up the hill at Launceston but struggled back to Trekenner to the Blacksmith’s shop. Here, talking were my Boss’s Father and the Blacksmith, so I stopped and spoke to them, then moved on. At that moment the wagon collapsed and the horses bolted, dragging the shafts at full gallop back to the farm, smashing the entrance gate and eventually coming to a stop in the yard! I ran after them and found them there in the yard. The Boss was soon on the scene and we got another wagon and cleared the road. Fortunately the Boss’s Father proved me blameless. It was quite a challenge with large acreage of wheat, corn, and root crops in addition to assisting with hand milking etc I enjoyed the work and I drove three large show horses, the horses were actually shown in agricultural shows they were very fit and to walk behind them 8 hours a day was very exhausting sore feet cheeks of my backside raw and in clouds of dust often soaked in sweat, such was the case to earn a living On the whole it was better at Penrest I worked 6 days a week but finished daily at five thirty, received 7 shillings a week and was paid for over time, in addition at the end, of the harvest, as a bonus, he gave me a three speed bicycle.

The food did not compare with Ruses Mill, but now my sister Millie was also working at the farm and did the cooking the food was much better. Really we got along quite well; it was within half a mile of home so Millie and I often went home. Father having moved to Trebithick cottage only ½ a mile away from where we were, Father being employed by Mr Gilbard of Trebithick, I became more grown up, had a few bob to spend and gradually renewed my thread bear clothes and I was able in a small way to take home a few gifts to the family, life carried on in the same way day in day out.

Sometimes on Saturdays after work I cycled into Launceston – I met one of the lads in there, who told me Percy Rowe had joined the navy, I was some what surprised, because Percy was from a wealthy family had attended Trekenner school with me, going on to Grammar school, by coincidence I met him I asked all about the navy, he gave me a rose painted impression (not so rosy when I joined and signed up for 14 years) anyway one day after my 16th birthday when we were not too busy on the farm I asked for a day off to go to Plymouth, I rode my bike to Kelly Bray caught the train to Devonport and made my way to the Recruiting Office, there I came into contact with two over fed Chief Petty Officers they gave me all the answers to my enquiries then began their own and got down to paper work , every thing about me, what I did, what education I had (NIL). Then a oral test, saying the 12 times table and spelling (my limit was little better than CAN). Afterwards they ordered a three badge good conduct sailor with 20 years service and no promotion ,to escort me to the naval barracks. He rode a bike I ran behind first to the doctor ,I might have had a swill down before I left had I known, next to the school room where I met a Warrant Officer school master. He was a little bit more civilized, told me the procedure, gave me paper and pen and to choose a subject and write a short essay, I completed it handed it in, he looked at my effort he looked at me, his face full of gloom – I really thought he felt sorry for me. Then he gave me the maths paper, which I was able to cope with well, and when I handed it in the school master’s face beamed! He said “If you can under stand Maths we will soon get you to under stand other subjects. Hence I was escorted back to the recruiting office, to join up. I was afraid to explore Devonport in case I got lost, but I got back OK. I did not tell the Boss anything, it was time to harvest mangles so all three of us got on with pulling, removing the leaves, carting for stacking in frost free stacks of 2 acres of mangles, This would take at least 3 weeks One evening I went home and told Father & Mother what I had done I think they were too busy with their own commitments to fully realize what I had told them it was only when Father was required to sign the trouble flared: his brother was a regular CPO in the navy served in World War One. He was in the battle of Jutland and was lucky to be alive, I well remember him especially when he visited us at Bottonett and took Father and I to Launceston, he would celebrate by taking us in a private room in a Pub nearly drenching Father with a couple of pints and my Father coming out very rosie-cheeked. Anyway I got Mother to sign the entry form, and then the Boss received a letter requiring a reference, so now he knew what I did with my day off. He must have given me a suitable reference but said he could not spare me for 3 weeks.

On Launceston Carnival day I received my calling up papers, rather disappointing as my sister and I had planned to attend. So was good bye to my friends, my faithful horses seeing I spent every day with them, daily fed and brushed them This is the end of my studies and ambition to work on farms, & to be a Farmer’s boy to plough sow reap & mow and to be a Farmer’s Boy where I was considered to be capable of doing any horsemanship jobs on a medium size farm and to equal a man in all respects. Farm workers were very low paid viewed as people of low intelligence but in my opinion they were very skilled, on large farms they are divided into four sections (1) Waggoners that applies to all horse work, ploughing harrowing rolling, etc to prepare seed beds to drill in the seeds to cut the crops and harvest them, provide all the transport of goods to and from the farm etc and of course to make sure the horses were comfortable in their harness ( It was common for horses to get sore shoulders) from about 1940 horses were replaced by Ford Tractors and implements. (2) Cattlemen, hand milking, putting the milk through the separator, feeding and the general welfare of cows and breeding of young stock. (3) Shepard’s feeding of the sheep, breeding, sheep-shearing, and the general welfare of the flocks. (4) The general Workman qualified to assist on all jobs and to build hay and corn stacks and thatch them, build and repair hedges, and the many other jobs in farm maintenance – a very skilled person. In fact all the farm workers had to be versatile especially during harvest and hoeing periods. The Farmer was employed in the general management also deciding what artificial manure; lime etc in addition to the farm yard manure would be required to produce good crops. (Now made easy by taking the analysis of the Soil) The Farmer’s wives and servant girls put the cream from the separator into a butter churn turned the churn until it became solid then made it into butter and sold it in local markets, they also provided refreshment in the harvest fields, and cooked special suppers for the work force during harvest period Really working on a farm was quite enjoyable especially in the Summer months, Winter months without suitable weather proof clothes being protected only by a sack around your waist and around your shoulders and a pair of nail boots and legging was pretty awful, never the less it was a joy to see the results of your labour with the crops coming up and maturing, and all the workers had a pride in seeing the farm looking tidy and well managed.

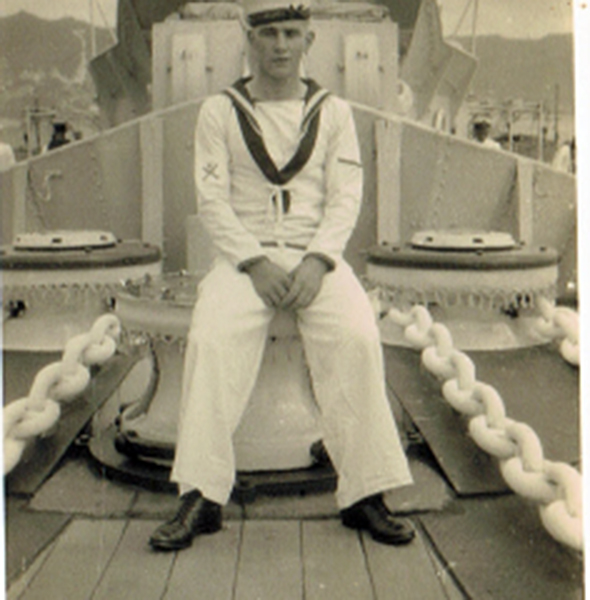

Now its November 4th 1926 a complete new adventure to my life joining the navy and only having seen the sea about once before and of course I am a volunteer, volunteer for what, it’s a good job the future is not ours to see, if so, I would have disappeared in space. I reported to the Recruiting Office, the same old three good conduct badge seaman commandingly escorts me to the boat pier widely known as Flag Staff Steps in Devonport Dockyard and was satisfied to have carried out his duties seeing me safely aboard a picket boat and sailing to HMS. Impregnable a boy’s training establishment, it consisted of three very old war ships joined by bridges and converted into lecture rooms, school rooms, mess decks, dinning halls, gym rooms and a swimming pool. The ships were moored in the inlet 200 yards from the Torpoint side. Fields near Torpoint were used for rifle drill, marching formations also recreation and the rifle range at Trevolve was used for shooting practice. I got off the picket boat climbed up about 30 steps and entered an office where I was faced with 3 men in peak caps, [who, I later discovered to be ship’s police] – they were the worse 3 men in the world let alone in the navy, they did not talk they barked at me they searched me and took every thing from me, then escorted me down to the boy’s mess deck, there I was given a coarse flannel shirt, a pair of white knee length shorts, a blue jersey, a pair of knee length black stockings, a pair of boots a cap, soap towel and tooth paste. I was then given string and brown paper told to strip off and dress in the clothes provide, parcel up my civilian clothes and give it to the ship’s police to be posted home. I now had the appearance of a ten-year-old schoolboy.

Next I was introduced to a boy with some kind of badges on his arm he probably had come from HMS Shotley where they joined at the age of 10, he was schooled and partly trained there, and he knew all the regulations he was put in charge of me, and escorted me to the bath room, told me to bath adding some disinfectant, next to the sick bay to be examined by the doctor, then to the barber to have my head shaven now having been absolutely demoralized, the boy mentioned some thing about having tea, it sounded good. There were about 40 boys in the mess deck, where we all eat; lived and slept, now lets not forget the tea my breakfast is well digested. There were four tables, 10 to a table, on the table there were 20 slices of bread, a slab of margarine, a tin of jam. The tea is made in a large tub filled with boiling water some course tea is added and a few tins of condensed milk, followed by raw brown sugar and stirred with the blade of a oar, it was collected in large tea churns, one for each table, it tasted awful, for the next 6 months I drank cold water, I had not noticed any beds around and I thought as I had come to stay this had escaped the charge boy’s memory, he soon issued me with a pile of ropes, strings, canvases etc which represented a hammock, mattresses, also two blankets, told me how to join it together, and my name was stamped on all the items, he then gave me a full demonstration how to sling it up to the deck above the hammock being 5 feet from the deck below, how to get into it and out, how to put a lashing around it, how to stow it and where to stow it. With most of the boys like myself fresh from home sleeping 3ft apart it was an experience well worth forgetting although from what was to come we were being nursed up.

The year 1926 produced its share of snow, so we were ordered to proceed to the upper deck at 6 30 am to sweep away the snow, first having to remove our boots and stockings, I felt frozen and there was the Petty Officer in charge with leather sea boots, knee length stockings, high neck white fisherman’s jersey in addition to his uniform and he said “ If you put more energy behind your brooms you would all be drenched in Sweat” and the deck was poorly lit, it was a common thing to knock your toes in a ring bolt This routine of scrubbing the upper deck was a daily event. During the next few weeks we were issued with all our kit, it consisted of a kit bag, ditty box, a hat box, a belt with a purse, sewing bag, boot brushes, polish, shaving gear, a jack knife, a seaman manual, an identity disc and about 40 items of clothing which were sufficient to meet all your needs no matter where you went or what climate you might experience. The disc was round with a hole drilled in it, made of fire and water proof material, my number was stamped on it (JX 128545) it was hung a round my neck with the order, this is never to be removed until you leave the navy. This ensured your identity at all times, especially in war conditions. Every item was stamped with your name in paint using a special wooden stamp with your name, which you used to mark any future issues. I then had to sew in round stitch my name over the painted name stamps; this took a couple of weeks. I was then instructed how to fold the clothes, roll it up, and pack it in the kit bag so that it would not crease; also how to lay the kit out for inspection, kit bags were kept in racks with your name showing Your kit bag acted as your ward drove, so if you changed your clothes, out kit bag, get out what you want and make sure you put every thing back otherwise you may loose the items and when you laid out your kit for inspection you had to pay for the replacements.

Having completed this phase, we are put into classes of about 40, I am 47 class and we begin instructions which consist of marching, rifle drill, rifle firing manning 4” and 6”guns – all very boring! Also school, gyms, anchor and cables, rope and wire splicing, knots, compass and helm, flags, semiforth, morse code, boats pulling and sailing, learning to swim, climb riggings, get experience of being 60 ft above decks, cooking and much more. Evenings we are landed for games in all weathers, on completion wash all our sports wear, and put it on the next day partly dry my class also trained in physical exercises and we took part in a display in Mill Bay Park watched by a large audience. Landing at Torpoint for games was a break because that was the only leave we were given for the first six weeks.

Although not being very keen educationally in past years I soon realized it was important and the advantage the boys had who had attended grammar school, l did manage to pass an examination to qualify for up to a CPO but being a second class boy ever reaching such a position looked impossible, it would have been advantageous to have passed for an officer, I had that to contain with in later years.

Unfortunately I had diphtheria while on the Impregnable, I remember reporting to the sick bay and being given a glass of opening medicine, that was the cure for all ills, but I needed some thing a little stronger I was very lucky to survive, having to spend months in the RN hospital, rather a laugh my kit bag went through an incinerator and it had shrunk up all my clothes and I had to be issued with new. After months the training was complete, we were individually tested in all subjects by senior officers and providing you passed given the rank of 1st class Boy with a rise in pay of 2 shillings a week.

It is now Jan 1928 with about 200 other boys I am drafted to HMS Marlborough, she is at Sheerness, each of us get our kit ready, hammock and kit bag, it is loaded on lorries and transported to Devonport Railway Station, we all march to the station, under the supervision of a Petty Officer & Warrant Officer and board a train for London arriving there we change trains to Sheerness. We board Marlborough and are given all the necessary instructions regarding our living accommodation etc. It was a relief to get away from Impregnable, and going to London was quite exciting.

HMS Marlborough is a 1st world war battle ship, still sea going, with 13” twin turret guns and 6”side guns all well maintained, we are sent here to put all our previous instructions into sea going practice, we are now going to work with the ship at sea, pitching and rolling in the waves. Our first main job is to coal ship, we dress in overalls and any old gear and man the coal lighters with shovels we fill sacks of coal which were hoisted on board emptied into the ship’s bunkers, this takes hours so we make an early start and late finish, it’s a dirty job ,I had previous experience of using tools but most of the boys were hopeless with shovels, we had to get in well over 1,000 tons, having completed this we had to clean the upper decks and paint work, hoses spouting every where, often getting drenched by an in experienced hose operator next. trying to get a bath with at least 20 others sharing 5 round tin baths and finally washing all your coaling gear.

Now its departure time the sea is stormy, we are allotted special jobs, the jobs for certain lengths of time, known as watches and times are denoted by strokes on the ship’s bell (strokes representing every half hour and hour) so no need to have a watch. We are now out in the English Channel, its blowing a gale, the ship is dipping her nose throwing tons of water back over the decks and rolling, we are on our way to Gibraltar, I am given the job as crow’s nest look out, it was very exciting seeing all the water rushing over the bows. The crow’s nest is attached to the mast about 50 ft up, it is reached by climbing ladders and due to its height, when the ship rolls you swing through a large arc and hope the ship will not roll over .The crow’s nest is connected by voice pipes to the officer of the watch on the bridge and you report all objects insight, we were trained in navy lingo has how to make reports.

My watch ended at 8 bells 4 pm, my chum Percy Rowe who gave me that wonderful impression of the navy before I joined came up to relieve me – I told him what he had to do, I thought he looked ill, I said “Have you put back my Tea” he said “There is plenty left for You” I climbed down and made my way to the mess deck, I found the mess deck flooded with water many boys lying in the water and sick as dogs, the smell was horrible, I lost my appetite immediate, and was terribly sick, it wasn’t very long before I joined the other boys lying on the deck, as we were still boys we were not required to keep night watches. The weather the next day was even worst, early the next morning I was on upper deck duty, still feeling miserable, the PO noticed I was looking a bit green, “He said get a broom and sweep out the Water” and huge waves were flooding the Deck,” it did take my mind off being so sick.

The weather did ease in the next few days, we were mainly employed with doing all the things that able seaman are required to do, we actually took over steering etc under supervision, also manning sea boats being lowered so far then suddenly being dropped on the crest of the wave. We soon entered Gibraltar, we are lined up on the decks, and remain there until the ship is anchored, then its more cleaning jobs and instructions. During the next 10 days trips are organized for us to tour Gibraltar and Spain, that was very exciting Now its time to return to the UK after about a day at sea we join all the other ships of the Atlantic Fleet and carry out manoeuvres, we go to our action stations, and do all the drills on the big guns, in fact its just like being at war. We eventually get back to Sheerness, given 10 days leave to go home, we never drew our full pay so much was held for such things as rail fares, the fare was quite expensive all the way down to Cornwall. Percy Rowe and I arranged to travel home together; it made it more pleasant as the route is rather complicated, especially seeing we had no experience of travelling. I found it very good to be home and away from all that discipline I called at Ruses Mill one evening they made me welcome and they were interested in my new experiences and when I went back Doris and Elsie saw me off at the station even Elsie wrote to me, and continued to do so in the following years, I am afraid at that time my letter writing wasn’t all that good it did not compare with that of Elsie’s but we kept in touch and on future leaves we spent time together.

In August 1928 we had completed our sea going training, promoted to Ordinary Seamen, once again back to men with many restriction removed, we were divided into groups according to our home addresses, Devonport, Portsmouth, and Chatham and from now on we would serve on ships to their respective bases this meant you returned to the base nearest to your home it had many advantages in cost of train fares and in getting home on short leaves. In fact Devonport was 20 miles from home so I could get home on a bicycle. The Devonport boys were drafted to HMS Comus so train again moves us to Devonport where we board Comus for more sea going experience and to qualify for Able Seamen. Comus is an old 1st war light cruiser her armament consist of 6” guns and torpedoes and she is part of the Atlantic Fleet, now we are actually the ship’s crew, we man the guns and carry out live firing we do all the cleaning, maintenance, painting (fancy painting the yard arms 60ft high, nerve racking) also the work in connection with exercises of the fleet.

We are away for three months either with the fleet or visiting places on our own then returning to Base for leave, really conditions are be coming more civilized we visited many Scottish sea side places and the people arrange entertainments, we also visited places in the Baltic, Sweden Holland Denmark all of which arranged special entertainments, we all enjoyed the cruise. After 8 to10 months we concentrate less on training more on useful jobs, I am given the job of engineer CPO’s mess man, there are 16 of them it is my job to prepare all their food, peeling all the vegetables making pastry, fancy cleaning 34 herrings for their tea, keeping the mess clean etc, but these CPO’s were older people, they had learnt their trade before joining and were more sympathetic, they helped me, treated me as a human being, were generous with a bonus at the end of the month, I saved enough to buy a motor bike and fortunately I had over come sea sickness. I lived in the mess with them. On one day a new issue of plates cups etc was issued and as soon as we got outside the break water we almost turned over ripping the racks from the bulkheads and smashing all our utensils, for the next 10 days we used old corn beef tins to drink out of, we spent most of our time in northerly Scottish waters Its now 3rd of Jan 1930, my training for an Able Seaman is complete, I have passed all exams I am promoted to AB (21 shillings a week) and drafted to HMS Vivid. After a week I am drafted to HMS Codrington.

The Codrington was a brand new destroyer powered by super steam power, can do 40 knots, with 5 guns and torpedoes, we were sent to the Mediterranean for 2 years and to be the leader of the 3rd flotilla, Codrington is very manoeuvrable, cramped living conditions and cut through waves causing huge volumes of water to wash over the upper decks, roll badly, and is generally uncomfortable. We take part in many exercises with the fleet with battleships cruisers destroyers and submarines numbering over 70, also we visit several seaside places in Greece Cyprus and Italy. After a few months we do a speed trial 6 hours at 40 knots we return with engine trouble, all the paint on the funnels is blisters, with others I am hoisted up the funnels to scrap off the paint, after 1\2 hour the rope supporting me burn through, I crash 12 ft smashing my wrist and badly bruised, I am sent to the hospital ship where I stay for 2 months, I return and carry on as usual I take the exam for a Leading Seaman and pass {it is usual to wait 5 years for promotion} soon after this Codrington is recalled to the UK to investigate boiler problems I am drafted to HMS Vivid to receive instructions in fire fighting and gases, I am then drafted to HMS Caledon, she is the same class as Comus she is moored up near the dock yard and is in the reserve fleet, she only has a skeleton crew.

As an able seaman you can choose to train for a wireless operator, signalman, torpedo man or gunnery. I managed to be selected for torpedo and was drafted to HMS Defiance she is moored near Saltash and we can land there, very convenient for getting home. Defiance is much like Impregnable divided into lecture rooms, school rooms etc now I can see Elsie frequently and I m sure of 6 months home, and its my base I shall always return to Defiance when not on sea going ships. The course as usual starts off with school followed by intensive instructions on torpedoes, mines, depth charges, electricity system, machinery electrically driven, telephones and exchanges Each week there were written and oral test, and a final test in all subjects (nothing came easy in the navy especially not being blessed with grammar school education) anyway with Elsie rewriting my note book and asking me questions. I manage to scrape through. . I now join H M S Adventure, a minelayer I work on mines, I have enjoyed the work and I get a recommend for a leading torpedo man so I return to Defiance. It was during this period that my parents lived at Brockle Ford 1933, in a wooden bungalow, I spent time there while my ship was at Devonport, it was at this time I lost my baby brother Tommy, I think he was about eight years old, he had some kind of blood disorder, we were all very sad, being the youngest we all use to make a fuss of him, we laid him to rest at Lezant Church.

Its Defiance to qualify for a leading torpedo man. This is a 9 months course, I probably will be home for 12 months and Elsie and I will be making the best of this, which we did, although the course is really going to be tough, I am semi confident Elsie is fully confident anyway after a struggle, good luck, and great determination, I qualify for a Leading Torpedo man. Really this carried huge responsibility on ships, especially in war time when you are in charge of men working on explosives and the whole electrical equipment, more so when engaging the enemy which did not enter my mind at that time but as it happen, it was not far away.

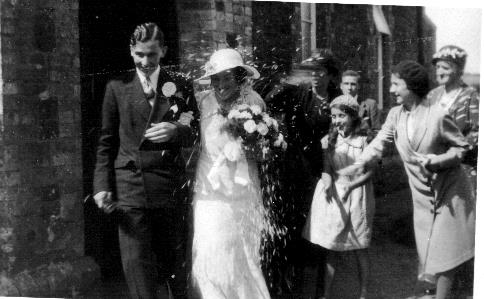

Now I am more relaxed but I know it will not be long before I am on the move it is now August 1934. Elsie and I decide to marry, all the family were agreeable and we marry at Trebullett, holding our reception at Ruses Mill, and our honeymoon at aunt Linda’s at Prawle and settled down and we were very happy, (and so far as that goes we were happy to the last, and throughout our marriage of 53 years she used her initiative and energy to achieve what was advantageous for both of us, she thought I knew, but she was the clever one, she was all I could wish for, let alone have.) After we got married and I was posted abroad for 2 years Elsie intended to carry on with her school teaching job and as before lodge home but she was disappointed to find out marriage cancelled her contract, by this time I was getting reasonable pay so we could manage quite well, so we rented rooms in Liskeard Road, Callington and Elsie was happy there and had many friends.

Now I am more relaxed but I know it will not be long before I am on the move it is now August 1934. Elsie and I decide to marry, all the family were agreeable and we marry at Trebullett, holding our reception at Ruses Mill, and our honeymoon at aunt Linda’s at Prawle and settled down and we were very happy, (and so far as that goes we were happy to the last, and throughout our marriage of 53 years she used her initiative and energy to achieve what was advantageous for both of us, she thought I knew, but she was the clever one, she was all I could wish for, let alone have.) After we got married and I was posted abroad for 2 years Elsie intended to carry on with her school teaching job and as before lodge home but she was disappointed to find out marriage cancelled her contract, by this time I was getting reasonable pay so we could manage quite well, so we rented rooms in Liskeard Road, Callington and Elsie was happy there and had many friends.

In Sept 1934. I was drafted to HMS Carlisle and preceded to South Africa for 2 years, but after about 6 months, a leading torpedo operator such as myself on HMS Dorsetshire who had married a South African girl wanted to stay on the station so I changed with him and joined Dorsetshire, which was returning to the UK. My brief stay in South Africa was very good I visited Capetown and some other nice sea sides towns the weather was grand, we swam a lot and it was a nice place to be, that’s if you had not left your wife at home, I joined Dorsetshire and we sailed straight home arriving 16 days later non stop, Elsie her Father and Mother waiting on my arrival I had some leave and settled down to several months refit. In 1935 Dorsetshire left for China, again they all came and saw me off. We sailed from Plymouth to Gibraltar, Malta, Port Said, via Suez Canal, Aden, Colombo, Singapore, to Hong Kong. We visited about 50 places, too numerous to remember outstanding were Shanghai and Yokohamma, where ever we went we were made very welcome, the visits were well organized, with free bus tickets and with free lavish entertainment and every body was polite and friendly. We saw so much – their methods of transport their architecture and statues and general culture.

Also the ship’s company organized plenty of entertainment – we had cinema several times a week, all kinds of sports and competitions on board and ashore included bingo. Dorsetshire was more like a liner than a battle ship, with good living accommodation and food, and because of the high temperature Chinese men served our food, apart from any pleasures we received we had a serious side, we did a lot of exercises by day and night as real as possible to war, actually clearing the ship for action and firing the big guns, with a lot of sleepless nights. So far as I was concerned I was happy in my job, I estimate our complement to be 700 with the electrical department employing 60. While on Dorsetshire I was promoted to a leading seaman, and I also passed for a Petty Officer and recommended for an instructor’s course at Defiance I also did vocational training ashore in motor maintenance and took the international driving test. Things began to look suspicious there was more emphasis on training, quicker promotion we heard Germany was arming. It was while I was in China that my father died, letters took six weeks to arrive and therefore I was unaware for that time of my father’s death. It’s unbelievable in this day and age with modern individual mobile telephones worldwide.

In Mar 1937 we ended our long voyage back to Devonport we had covered 31000 miles. On the dock among many others I spotted Elsie and her Father and Mother it’s been a long wait to see them. and we are extremely happy to be united again. Regards my trips abroad, it has been an experience and an education to see the conditions and poverty many people are forced to live with, it was common to see homeless sleeping on the pavements even in 1935 and suffering from malnutrition.

I celebrate my home coming with 6 weeks leave and Elsie and I go to Prawe for a holiday. It’s a bit limited as Elsie has moved from Callington to a large house at Coad’s Green, she has taken the head mistress of the school as a lodger also let some rooms to a Mr Tredinnick.

My leave ends and I report back and I am promoted to a PO drafted to Defiance and start this instructor’s course (alright now for about a year, I have worked it very well and my pay has improved) as a PO I enjoy many privileges, you live in a mess apart from lower ratings before you lived with them and as a LS you were always responsible for their conduct, now when not on duty you can relax, no manual work of any description you don’t have identification cards which are collected when going ashore, PO’s do not fall in to be inspected, they tick themselves off and salute the Officer of the watch on going on leave , they arrange their duties with each other, and if you want a special night off you can arrange it, above all you have mess attendants .You wear the ordinary sailor’s uniform for 1 year then you wear cloth suits brass buttons and peak cap with the appropriate badges denoting your qualifications. I am on this course finding it mighty difficult but pass or fail I am home for 1 year that is my main consideration, especially as we were expecting our first child, actually born in December a girl we named her Christine.

By April 1938 I had completed the course and qualified for a torpedo instructor this is the most senior position possible you can get on the lower deck, I did a few months instructing then I was drafted to HMS Guardian to take charge of the entire electrical equipment gyro compass, telephones and exchange, depth charges, paravains with 10 staff. I had worked on many other ships but not in charge, at first it was easy going, we were at peace, Guardian was a net layer, a target tower, and a photography ship. With a crew of about 200, she was based at Devonport and normally she would work in the vicinity of Portland or in Scottish waters. She would return to base at three monthly intervals and give leave, her work load was laying nets around harbours to prevent submarines entering – its just a practice run in peace time, but in war it is of the utmost importance. Up to this period with Guardian frequently in Scottish ports I was able to have a look round Glasgow, Edinburgh and many other places. I even attended the Empire Exhibition at Edinburgh. Also while at Portland, Elsie and Christine stayed at Weymouth, – I had a car and drove home some weekends, so when war broke out our lives were turned up side down, Elsie was living at Coads Green when war was declared; her neighbour an ex CPO came across and told her “You won’t see Jack until the war is over”! We worked 24 hours a day in two shifts , mainly in the Scapa Flow area, this meant my electrical gear was in use 24 hours a day especially the winches which were strained well above their capacity, and it did prove difficult to maintain them to 100% efficiency which was expected. Furthermore we had more up to date anti air craft guns and digital control, echo sounding and much more installed all of which I had no previous training. If that wasn’t enough I was often rowed across to accompanying trawlers to repair their ‘asdic’ – they were screening us from submarines, more by luck than judgement! I was able to get the gear working, and really this impressed my very senior four ring captain and he encouraged me to set my sights on becoming an officer. The first break we had was when we stuck a rock, and put into a dock in Scotland, I think it was 5 days of which 3 or more were spent travelling to get home & back, our second child was expected and I did arrive home the following day.

There is quite a lot I could say about our thrills, we were often machine gunned! I well remember hiding behind a canvas screen and finding bullet holes just above me. On occasions at sea we would feel our ship side buckle followed by a bang and think our turn had come. I think the worst was at Scapa Flow when a German submarine got into the harbour where we were boiler cleaning, and it torpedoed HMS Iron duke and killing 800 young sailors and I attended their mass funeral a few days later, that really was a shocker I was standing up to the circumstances very well but I did begin to smoke, and to help me to sleep I temporary drew the rum ration.

Anyway, with this Officer business I saw a chance of being home for at least a year so I took it a step further and took the exam in seamanship and passed but there was an education test similar to that taken at Dartmouth and a very difficult course at Defiance, Fortunately I had attended night school on all the ships I had served in, so I was drafted to Defiance. I first had to take this Higher Education Test and did not pass. (I knew they were desperate to train the likes of me with experience for warrant officers but unwilling to lower the standard) so they allotted me to H M S Prince OF Wales, she carried an experienced school master and I would be recalled when I had passed, this was cancelled (she was sunk on her first maiden voyage with a great lost of lives). I first did a special course at Defiance it consisted of four of us with an MA breathing down our necks 8 hours a day for 4 months until I passed this H E test followed up by the standard course.

The circumstances were terrible, Plymouth was being continually bombed night after night Defiance and the oil tanks at Torpoint were hit, people were nightly leaving Plymouth in hundreds for what shelter they could find between Saltash and Callington, they were not even safe there I even encountered craters out at Stoke Climsland. My course was often interrupted by having to go into Plymouth and take charge of men demolishing buildings that were causing a hazard, at times this proved very dangerous as we under the circumstances took risks. I remember one morning we were called out after Plymouth had taken a battering, we loaded our gear into a lorry in the dockyard and every street was blocked it took 2 hours to reach Derry’s Clock, on that day I was attempting to blow down a large wall which was originally part of the Prudential Insurance Building, the Army had failed to move it, I mounted a three length piece ladder and chiselled out a place and put 5 lbs of TNT in the hole, it immediately burst in flame, my legs never touched a bar of that ladder I just slid down 30 ft in a flash and bolted but as I was earlier instructed TNT has to be detonated to explode so it just burned, we did a repeat and brought the building down, it was photographed by Plymouth City Council. There were other occasions when we stayed in Plymouth sheltering over night using our TNT boxes for pillows and starting our work as soon as possible after the raids God bless the Salvation Army they gave us food, where they got it from puzzled me, the place was full of fires smoke over hanging walls craters and what the ruins contained was a mystery no words can describe I had to make up time lost from instructions evenings it meant I could not get home until 9 pm also we had to take home heavy text books to study, most of the officers lived in Plymouth and did not get much sleep with the raids and they did their best to prevent me from getting any, but a senior officer once wrote on my records “He has above the average Intelligence”, so now is the time to make use of it, blow the text books and make the most of the time with the wife and kids. Any way I completed the course, I had enjoyed getting some time at home with the family and I was promoted to a warrant officer I am now sent to Portsmouth to do a Coastal Navigation course, lovely, Elsie and the kids can come up for 3 weeks which they did, we secured lovely digs and had a lovely time, apart from a few air raids which were not in the our vicinity.

Its now August 1941 and I am appointed to HMS Beagle an old destroyer with torpedoes, half her guns removed and replaced by Depth charges, she is employed on convoys to Russia and based in Scotland. So I have to take a train to Scotland which takes days rather than hours, apart from being armed with a first class ticket I am lucky to get enough room to stand, there are thousands of service people traveling with their kits the platforms are jammed full of people resting sleeping using their kit bags for pillows and the station is almost in darkness., in spite of every effort by the voluntary workers its impossible to get refreshments I eventually get on board greeted by the Captain who strangely enough was an extremely nice man and introduced me to my fellow officers including the one I was relieving, it was lunch time and I was glad to sit down to a good meal I spent the next few days taking over from previous Gunner (T). There was quite a lot to takeover and be responsible for, and finally having to sign his account book stating that all armament was in perfect working order all ammunition safely stowed and the correct amount on board, on completion I had to get a new account book with hundreds of printed headings and make the appropriate enters from his book. His book had to be sent to the Admiralty which we all had to do at times, complicated old job keeping these accounts especially in rough arctic conditions and you had to do this at sea because a signal of your requirements was made so that when you got in harbour the ammunition lighter immediately stocked up your ammunition and you were ready for immediate departure, we received training in accountancy and received extra pay.

The weather in the arctic circle was very cold 20 degrees below zero and generally it was difficult to get to the bridge from my cabin, with huge waves breaking over the upper deck, often being almost washed over board getting soaked and had to remain in wet clothes for four hours, which became stiff in the freezing conditions. The bridge is where every thing is controlled from it is manned by two watch keeping officers with the Captain stationed in a make shift cabin on immediate call. One keeps his eyes glued to binoculars and attend to route jobs, the other has a card of alteration of courses and times and a stop watch, the course is altered at short irregular intervals, known as zig zagging, a steady course would provide an easy target. You are in company with the convoy and other destroyers and it is vital to make the correct turn at the correct time and keep in station, this is difficult enough under normal circumstances but dashing away and attacking a sub then getting in station especially in pitch darkness is worrying. I did my times on the bridge, but other things kept me busy action stations, keeping the guns, torpedo tubes, depth charges etc free of ice with steam jets every minute 24 hours a day and many other jobs, such as accounting for expended ammunition, preparing a signal so that your requirements were immediately available on reaching shore, and you were ready for a rapid departure. I also shared the censoring of the mail for all the ship’s company which bore your stamp and signature this was a very irritating job just when you thought you had a hour to relax and was thinking of scribbling a few lines to the wife, the first chance for a fortnight to post a letter, down came a sack of mail and you had to read each letter carefully in case it contained any useful information to the enemy. The job had to be done correctly as the letters were checked at random by the Post Office.

You did not undress and we were tired and dazed, it was not much relief to go down to your cabin and find ice hanging from the ceiling, it was difficult to find some thing to laugh about but I had to supervise the issue of the rum a PO in the supply branch worked out the precisely total amount, a rating using a tot measure issued the amount for each mess, but he held the tot measure with the tip of his thumb in the top which resulted in he had a small amount left hoping to drink later and forget all his sorrows, but I being an old able seaman, knew all the tricks, what a daggering look he gave me when I said “ Pour that down the Drain”

The worst trip we had was home bound with PQ 11. We encounter two German destroyers, they were new and far superior in guns and technology to our old 20 year clapped out ones, we fought them on and off for 4 hours firing hundreds of shells and going in to fire torpedoes when we came under a terrible peppering, but with the skill of our Captain we got away with minor damage, surprisingly the Germans disappeared, but there was a reason for it, unknown to us. When you are on these convoys you have no idea of the complete planning, but at the time we were being attacked a cruiser force was patrolling some miles away, but did not come to our aid, the reason was they had been damaged by subs one the Edinburgh was in danger of sinking, and the reason why the destroyers left us was to sink the Edinburgh.

I was with the crew of the torpedo tubes which were stationed under the barrel of a 4 inch gun and got gun blasted, resulting in me being invalided at the end of the war. I did a few more trips to Russia but the hospital where I was being treated decided I should be relieved, so I returned to Defiance. After a few weeks I was sent to Mount Wise, no idea what for, I was told not to leave Plymouth, Elsie and I over came this by getting accommodation in Plymouth. I did some special training for about a month, then out of the blue I was sent back to Defiance- it was rumoured it was to invade the Channel Isles.

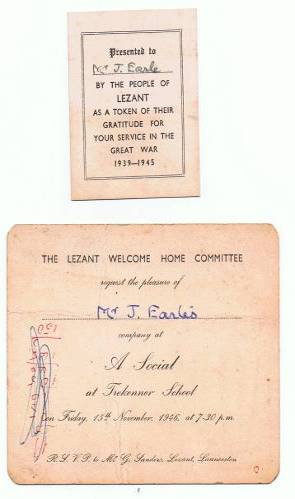

I was then sent to H M S Norfolk, a country class cruiser with some electrical staff to install emergency cables and a sound powered communication system, (phones that generated their own power) this lasted about 10 months, in the mean time Norfolk was patrolling the Denmark Straits, also covered the African landing and escorted Mr Churchill to Canada to a summit with the President of the United States. On completion of the work I returned to Defiance, only just in time to being on Norfolk when a German Pocket Battle Ship damaged her. From then to the end of the war I acted as a relief to sick Gunner (Ts) serving on several ships, one being an officer’s training ship for ratings, here I was amused to discover my messenger was a C of E minister, I also spent time at Bath and Yeovilton organising an over sea torpedo supply base. I was promoted to a Commission officer and in a short time invalided with approximately 20% defective hearing I did not argue about this, but I considered it to be worst There were complications in getting invalided, at Defiance I spent some time working as an aid to the commander he was a terror and feared by all the officers he had charge of all the training also other establishments I worked in his office, although he demanded hundred per cent efficiency, I satisfied his requirements and got along quite well with him, he thought I ought not to be invalided, he got in touch with the RN hospital, they explained that the only chance of my hearing improving was to work in the minimum of noise. He did his best for me in granting 2 months paid leave and giving me excellent references, apart from losing a job of 19 years I felt glad to be able to spend the remainder of my life with my wife and family.

We spent the first two weeks in Cheltenham with Auntie Hilda, returned to Kelly Bray where we were living. I reported to the office of the Ministry of Employment at this time you were directed where to work, I was given options I could do time at college to get my City and Guilds with a view of being employed by the Education Authorities or I could be directed to an electrical company, or I could find an electrical job locally with their approval. At this time my nerves and hearing not being very good I got work at Callington electrical supplies at one third of my previous pay, with the approval of the Ministry of Employment, I did do other jobs which were better paid. Eventually we bought a small farm at St Breward, and farmed for a short time we then moved to Chilsworthy Beam to another farm. I am by now much better in health, we manage to get a jersey herd of cows, many pigs, poultry and decent farm implements my time is completely taken up slugging on the farm I am fortunate to employ a farm Manager, my wife Elsie, we are doing all right we are really finding out how to make the best of life we are all interested in the farm, all happy.

Christine and Dorothy going to work in Plymouth, and a few years later getting married, some time earlier Elsie and Christine had bought a couple of near by cottages, when Christine got married Elsie bought it from her and in 1970 Elsie and I spent our retirement there. In the mean time Dorothy had a son Peter and in order to resume her work in the bank she bought the other cottage, Elsie and I taking care of Peter. We did this for several years and he made our retirement quite exciting, Elsie having spent many years as a teacher, but did not have the opportunity to attend university, she took a passionate interested in Peter’s school work I think she made him a vehicle of her own ambitions and he later went to University and gained his First Class BA and joined the teaching profession.

We were very happy until late 1986 when Elsie became seriously ill and in spite of all our efforts she passed away on Jan 22nd 1987. We were deeply shocked and sad we laid her to rest at Trebullett. The bottom of the world had fallen out for me after 53 happy years.

I remained at the cottage for just over two and half years I then married Gertie, Elsie’s sister and lived at Coads Green. It was good to again have a partner, and I enjoyed the following four and half years, sadly Gertie became mentally ill, and even with much help from my daughters and others for several months, she had to go to hospital permanently for two years. With Dorothy’s help I was able to visit her frequently, she passed away on Nov 26th 1996 and I felt very sad as we laid her to rest at Trebullett. In the mean time I returned to live at Chilsworthy Beam with Dorothy and George, where I have received wonderful care and kindness. At the age of 91 I still enjoy good health and I can scarcely believe my own lifetime – growing up in poverty, making something of myself in the navy, surviving 2 world wars, seeing nuclear weapons, the motor car and even now mobile phones and computers.

Postscipt

My Grandfather continued to enjoy good health for several more years – he added various sections to this Account which we have omitted but deserve mention to show how alert and interested he was in the world around him. He wrote about his concerns about news items, about the poor of the world (noting that he had visited many of the places in WW2 and that it seemed sad that not enough had changed for those people, in all those years). He was also keen to talk about the war in Iraq and the various consequences of the national outbreak of Foot and Mouth (as he had been a farmer, for many years after the War).

‘Gramp’ was immensely proud of his family and talked of his joy at becoming a Great Grandfather to Elizabeth’s Children (Christine’s Daughter) and then to my two daughter’s Lucy and Ruth (in 2005 & 2006). He also loved talking about how he had cared for all of us in past days and took immense pleasure from the shared memories (teaching me to drive for instance). He made occasional journeys to Gloucester (spending a week at a local holiday cottage on two occasions) to see my family but was happy in Cornwall – smoking his ‘pipe’ and enjoying sitting in the two field we still owned at Chilsworthy Beam. While generally healthy there were occasional scares – he fell several times and needed to be taken by ambulance to Plymouth, for treatment, a few times. He agreed to spend short periods in ‘respite care’ in Callington and Albaston – and always seemed to return home fresh and well.

The turning point came with the unexpected death of George (my Dad) in 2007. This made it much harder for Dorothy (my Mum) to care for my Granddad and after much deliberation it was agreed that they would both move to Gloucester to be nearer to me. Fate seemed to play a part – they bought a lovely house near to a lake with plenty of birds and although ‘Gramp’ spent more time in his room he had lovely food – as well as first rate care from my Mum and occasional visits from his other daughter (Christine) who came up by bus, from Okehampton.

Slowly it became apparent that he needed more intense medical care and eventually after enjoying some respite stays there, moved into permanent residence at Wooton Rise Nursing Home in Gloucester. He was blessed with caring staff, daily visits from his family… and of course he relished in talking of former times [as well as the current news] and proudly displaying pictures of his ships from World War Two, on the walls. On his 99th Birthday he was recovering from an infection, in hospital, but we all had a family get together. He again seemed perky and was excited to get a card from a former shipmate on HMS Dorsetshire. He resolved that he would meet up with or contact his wartime colleague when he got to 100!

Sadly ‘Gramp’ passed away peacefully a little short of that landmark – he died on Sunday 24th January 2010 and was buried a week later in his beloved Cornwall in the graveyard alongside many other family members. I have included the speech given at his funeral to remind you of what was such a special life – one that we can genuinely celebrate and remember with fondness and fine memories – W J Earle (Jack / Dad/ ‘Gramp’).. we will miss you and we thank you for writing this ‘story’ as you call it!

Peter Jeffery (Grandson)

Visits: 310