.

In 1774 a route was planned for a canal from Bude by Edmund Leach and John Box. And late in 1774 an Act of Parliament was passed ‘ for making a canal from Bude to the river Tamar in Calstock parish,’ which would have affected the district of Launceston. This Act gave permission ‘for making a navigation from Morwhelham Quay in Tavistock parish to Tamerton bridge in Cornwall, and also a collateral cut from Poulston bridge in Lifton parish, Devon, to Richgrove (Ridgegrove) Mill in St. Stephen’s parish, Cornwall.’ In 1777 John Smeaton estimated the costs of the canal scheme to be about £119,210, and said Cornwall was not well adapted for construction of canals, and suggested a route over Grinamoor, near Week St Mary would reduce the length of the canal by about 15 miles, he also suggested variations on the locks, depth of rivers, the making more use of the river system to Greystone Bridge and a canal following the Tamar from there. This part tied in with the Sewage & Manure Canal then being put forward under George III., from Morwellham, which was planned to end at Tamerton, with a branch from Polson Bridge along the Kensey valley to Ridgegrove and Launceston.

Smeaton’s report appears to have killed off the whole idea, but in 1785 Edmund Leach came up with another plan which was not acted upon. Another plan, this one by John and George Nuttall, in 1790’s for a canal between Bude and Holsworthy, this time using iron rail and canal, was put forward. In 1793 an American, Robert Fulton, put forward plans for a double inclined plane which would be used at Hobbacott when the Bude Canal was constructed.

However, Napolean put a stop to all that when he began his rampage across Europe, the British calling up all the spare labour force of the country and so doing away with the reason for the canal put forward in the first place. In 1814, after the wars with France, Mr Harwood of Tackbeare, and Mr Braddon, of Newcott, approached Lord Stanhope and put forward the case for the canal and the original idea of using up spare labour in the district and for the agricultural reasons. This was again foiled by Napoleon when the army recalled the labour force. Lord Stanhope died in 1816, and Harwood and Brandon then approached the new Lord Stanhope, with Mr George Call, of Vacy, North Tamerton, and as a result engineer James Green and surveyor Thomas Shearm were engaged to survey a line for a canal from Bude. A meeting was called on 5th November 1818, to make arrangements for subscribers, and an Act of Parliament was obtained in 1819; The Bude Harbour & Canal Company was formed with 330 subscribers, including Lord and Lady Stanhope, Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, Sir William and Lady Call, Mr George Call (later the company’s first chairman), William Arundel Harris and Sir Arscott Molesworth. Many other business men and worthies of the time also took out shares in the company. The Act was obtained on 14th June, 1819 for construction to begin, and this was put into operation on the 23rd July, 1819, being well reported in The Exeter Flying Post.

As a result of the Act of 1819, plans were put in place for the construction of the Bude Canal, terminating at Druxton Wharf, some four miles from Launceston (being prevented from being brought nearer to the town by the influence of the Duke of Northumberland, then owner of Werrington). It is rumoured that the Duke was originally receptive to the scheme, but after a meeting to discuss the proposed route of the canal, a mock plan showing the route to pass within a couple of hundred yards to the Duke’s residence at Werrington, was left behind. This joke backfired as the Duke, quite incensed by this, refused to cooperate any further, and so the canal had to be terminated at Druxton. The well-known engineer James Green and Thomas Shearm, a surveyor, were approached to devise a plan to that end. Green’s conclusions included the factor that because of rising land and a poor supply of water, most of the ascents would be by inclined planes, which were cheaper to construct, saved water and were quicker to use than a flight of locks. The canal for the first 2 miles would be a broad canal, capable of taking vessels of 40-50 tons. At the seaward entrance, a sea lock would be constructed to allow sailing vessels of 70-100 tons to be admitted to the basin for trading. In 1835 the Sea Lock was enlarged to its current dimensions to take larger seagoing vessels of up to 300 tons. Green also recommended a breakwater to protect and improve the harbour area. This would include changing the course of the River Neet from discharging along the northern edge of Summerleaze Beach, to its present course, which would create a channel to give depth for vessels manoeuvring on neep tides. Inland from the end of the broad canal, the canal was to be narrower and use tub boats, which had wheels to traverse up and down the inclined planes. Power was by a continuous chain towing the trains of tub boats up and down the plane. The chain was driven by power from the underground waterwheels set in wheelpits at the head of the plane. This was to be the means of power for 5 of the 6 planes namely, Marhamchurch, Venn, Merrifield, Tamerton and Werrington. The largest plane at Thurlibeer, now called Hobbacott Down, which was 935 feet long and raised the level of the canal 225 feet, used water power, but in the form of counter balancing ‘buckets of water’ (cysterns) in 2 wells of 225 feet depth. Each ‘bucket’ 9” diameter, 5’6” depth and holding 15 tons of water, would rise and fall in the wells. A valve on the bottom of the ‘bucket’ released the water, which returned to the canal via an adit tunnel emptying into the boat bays at the foot of the plane.

James Green estimated that the total cost of the construction of the canal and improvements to the harbour to £128,341. After consideration, the proposers applied for an Act of Parliament, which was obtained in 1819. The same year the Bude Harbour and Canal Company was formed, amongst the 330 shareholders was James Green who had been appointed engineer in charge of construction. Work commenced on 23rd July 1819 with the local labour force being supplemented by navvies brought in from other parts of Britain, which did not go down well with most local people (exactly as the railway, and later roads contractors did for the modern dual-carriage and motorways, bringing all the same old problems again and again). This canal was to be from the sea at Bude, up the river Neet for nearly three miles and then to Ridgegrove, Launceston, with a branch to Holsworthy from Red Post. The King George Canal was put in from Morwellham Quay to Tavistock, but not along the Tamar to Tamerton, thus putting an end to the idea of making most of Cornwall an island. Work began on the canal on the 23rd July 1819; by 1821 the basin was complete, the extension to Druxton was called off. On 8th July 1823 the portions of the canal from Bude to Holsworthy and the reservoir at Upper Tamar Lake, and to Tamerton Bridge were officially opened. The final cost was just below £120,000. The canal as built was 35 ½ miles in total and comprised of the main line from Bude to Blagdon Moor Wharf, near Holsworthy, with a branch from Red Post to Druxton Wharf, nr. Launceston and a feeder arm from the newly constructed Tamar Lake (now Lower Tamar Lake) to feed the canal with water. The canal was unique, in that it was constructed for agricultural purposes, the transporting of lime rich sand for the improving of soil.

By this time capital was low and the company requested a loan of some £20,000 from the Exchequer Bill, Loan Commissioners; this was backed by a report from Thomas Telford who acted as an advisor to the Commissioners – a £16,000 loan was sanctioned. With this loan work was begun on the Druxton line in the summer of 1824, by which time 100 boats were operating on the canal. After a loan of £4,000 was obtained from the Commissioners, the work was finally completed in 1825. The Hobbacott Plane was 935 feet long, and rose 225 feet: it was worked by water power which involved two wells sunk at the top of the plane, corresponding to the depth of its vertical rise. In each well the descent of the large bucket, 10 feet in diameter, 5 feet 6 inches deep, suspended on a chain wound over a drum, and containing 5 tons of water each, provided the power for raising the boats. As a standby, a steam engine was kept at the top of the plane for emergency use (which was often). Fully loaded boats took 4 minutes to ascend the plane under water power, 8 minutes by steam engine. There was also a water wheel at Hobbacott of 9 feet in diameter used to provide power in the blacksmith’s shop. Debts of the Canal Company were finally paid off in 1870. The canal really was a success, the farmers had improved their land significantly by using the cheaper sand and the land value increased beside the canal.

The tub boats were 20 feet (6.1 m) long and 5 feet 6 inches (1.68 m) wide, and carried about 20 tons payload; the usage of tub boats was not confined to the Bude Canal. They were commonly operated by coupling between 4 and 6 together and hauling them – by horse power – together. A “train” of boats could therefore be 120 feet (37 m) long, and on the very sinuous alignment of the canal, the train must have been difficult to pass round sharp curves. Steering was possible by manually altering the connection between adjacent boats, using handspikes. Each boat had four wheels 14 inches (360 mm) in diameter for running on the inclined planes; the boats were hauled up and down individually. The operation of lining the tub boats up with the rails, at transfer from canal to plane, must have been difficult. Once engaged with the continuous chain, it would have been impracticable to stop the motion momentarily while the wheels were guided to the rail channels; but no record is available as to how this was achieved.

However, serious problems with the state of the newly finished works were discovered, although in the circumstances of a locally promoted scheme with novel technological aspects, the canal as built was better engineered than it might have been. The chains on the inclined planes were constantly breaking, the rails broke, and other mechanical failures were frequent, and physical damage from careless boat handling was also common.

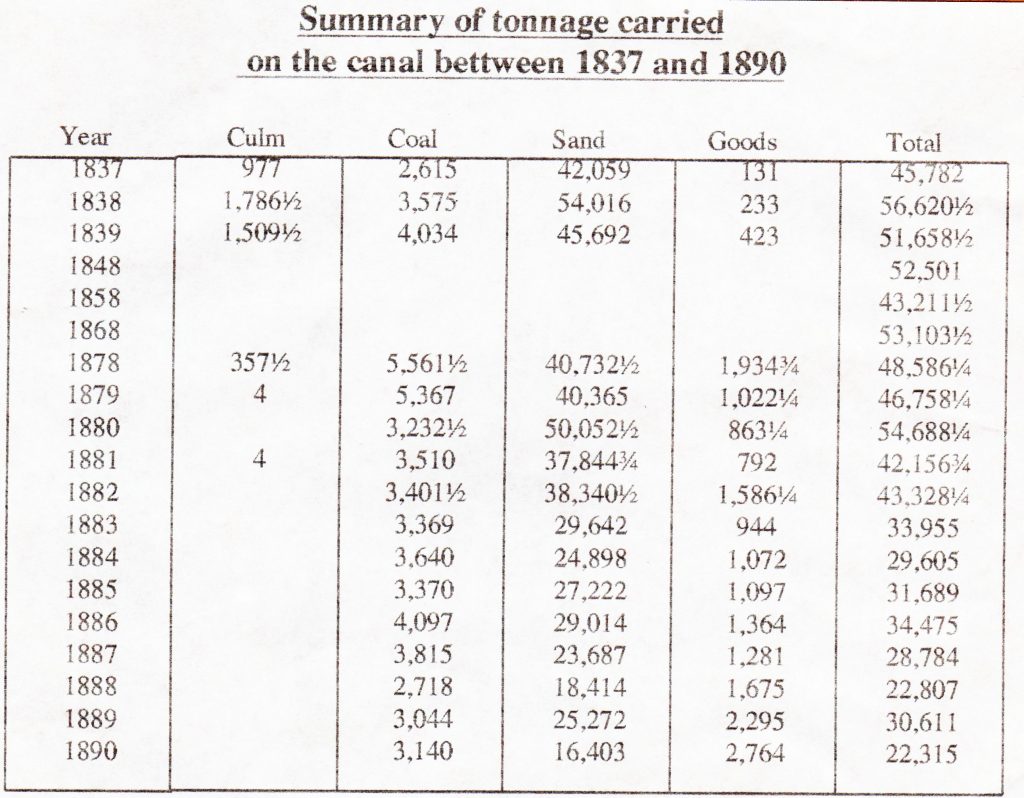

However the rich sand was successfully carried to farms near the various wharves in large quantities, and other merchandise was also carried, particularly coal from South Wales. Traffic picked up in the 1880’s, and when the London and South Western Railway reached Holsworthy, the canal carried significant volumes of the sand to Stanbury Wharf for onward conveyance by railway; the mile or so between the wharf and the railway station must have been negotiated by horse and cart. By 1865, the Launceston and South Devon Railway had reached Launceston. There were plans to extend the Railway line to Druxton Wharf from Launceston, but this never came to fruition, possibly due to the cost.

Nonetheless the arrival of the railway soon spelt the ultimate doom of the canal: manufactured fertilisers had become commonplace and cheap, and they could be brought in by railway, so that the demand for the local sand was diminished considerably. When it became obvious that the canal could not survive, some directors proposed obtaining parliamentary authority for abandonment, or selling the canal outright to the railway company, or anyone else. However legal conditions agreed at the time of construction gave certain landowners rights to take water from the canal, and they would not give up these rights without compensation, so for the time being the proposals for disposal were frustrated. The canal Company applied for an Act of Parliament to close some of the canal in 1891 and the branches from Red Post to Druxton, and Brendon Moor to Blagdon moor were closed, but with the Feeder arm continuing to be kept open because of the water rights. The towns of Stratton and Bude were granted rights to the water brought from Upper Tamar lake to the top of Hobbacott plane, for which they were to pay 1d. per 1,000 gallons, up to 60,000 gallons per day. The local authority had to construct and maintain the necessary sluices, filter beds, and piping.

Sales of materials and equipment were held at Druxton on the 14th September, 1891 by Mr Kittow, and at Hele Bridge on the 26th October, 1891. Landowners were offered the option of purchasing canal land adjoining their own at a reasonable price. On the 1st of January, 1902, the canal was sold after protracted negotiations to the Stratton and Bude Urban District Council for £8,000, one-fifteenth of the original cost. This enabled them to supply domestic water in due course to the villages in the district from the canal’s Tamar reservoir. In 1967 Tamar Lake became the property of the North Devon Water Board, and all that remained in the ownership of the Bude/Stratton Urban District Council was the two-mile length from Bude to Hele Bridge. The works became the responsibility of North Cornwall District Council when English local government was reorganised in 1974.

Above Bude sea lock. Above all that remains of the canal at Druxton Wharf.

Visits: 329