By the Rev. Kenneth E. Hyde

Puritans

The first, Presbyterian, period can be traced back certainly to 1637. although at an earlier date there are hints of Puritan influences in the town,. Gasper Hicks, the vicar of St. Mary Magdalene in 1630 was a Presbyterian, later to be ejected from the living at Landrake. In 1637 William Crompton came to St. Mary’s from Barnstaple, where he had been ‘a lecturer.’ “He was much followed and admired by the puritanical people of that place and in the neighbourhood; but his doctrine being not esteemed by many orthodox, or as those of his persuasion say, that he was envied by the Vicar thereof, because he was better beloved than him, he was forced thence, by the diocesan and ecclesiastical power, and thereupon receiving a quick call he removed to Launceston, where being a preacher in the church of St. Mary Magdalene, he continued in good estimation among the precise people about four years, and then to their grief he was untimely snatched away by death in the prime of his years.” His son followed his father’s opinions and was afterwards an eminent Nonconformist in Devon, being ejected later from the church at Cullompton.

Crompton died in 1642, and for six years there was no continuing minister. A successor was appointed in 1648, when the name of Joseph Hull first appears in the parish register as clerk. Hull had been born in Crewkerne, Somerset, and was Rector of Northleigh, Devon, from 1621 to 1635, when he emigrated to New England with his wife and seven children. He did not settle down, and after several moves returned to England and came to Launceston. The following year, on January 23rd, 1649, “was baptised Rubin son of Joseph Hull, Clarke” and a similar entry follows at almost yearly intervals until 1654, when the birth (not the baptism), pf John Hull is recorded on November 25th. Soon after this Hull left Launceston, because of his growing family; John Tingercombe wrote of him: “Tis hoped the man is godly. He has a very greate charge of children neare twenty. Some say more.” A latter hand has tampered with the name of his son born in 1651, and other entries directed against Puritans in the same hand suggest that Hull was a Puritan. Other proof of this comes from the fact that the Council of State in October 30th, 1655, approved an Augmentation of £50 certified by the Trustees for the maintenance of Ministers to “Jos. Hull, minister of Launceston, co, Cornwall.”

A Base Rogue

He was succeeded by William Oliver, another Presbyterian. Oliver, whose father was a gentleman of the country, had received a liberal education. He was a critic in the Latin and Greek tongues, for which and his other excellencies he obtained a Fellowship in Exeter College, from which he removed to take the pastoral charge (of Launceston). He was a good scholar and an excellent preacher, for which he was valued by the gentry of Cornwall and Devon. However, he did not escape criticism in Launceston, for in 1661 Peter Blewett gave securities for good behaviour “for having said that Mr. William Oliver, minister of this town, was a base rogue.” His appointment is interesting; a manuscript at Lambeth Palace gives a memorandum that on December 10th, 1656, “there was shown to the commissioner on approbation of public preachers, a nomination by the Mayor and Commonalty of Launceston of Mr. William Oliver, to the curacy of the Parish Church of Launceston.” This can but reflect the influence of the Puritans in the town at the time. One local celebrity was well known for this point of view. Thomas Gewen, of Bradbridge, in the nearby parish of Boyton, a former auditor to the Duchy of Cornwall, was elected to Parliament in 1647, although later, through his frequent opposition to the military party during tyhe second English civil war, he was excluded in “Pride’s Purge.” He had strongly advocated a Cromwellian monarchy and a House of Lords, had sought the exclusion of the Bishops from Parliament, “a stricter observance of the Sabbath,” the abolition of ceremonies unwarranted by Scripture, and the provision of able and laborious ministers of religion.” He was a shrewd man, well trained in administration, and a member of various Parliamentary committees in Cornwall. But he shared the common prejudice against the Quakers, and must be held partly responsible for the imprisonment and suffering which George Fox endured in Launceston Castle. Fox, with his two companions, Pyot and Salt, had been arrested at St. Ives for distributing religious tracts and brought to Launceston to await the March Assizes in nine weeks time. This trial proved to be a farce, and the conviction resulting in their imprisonment was the technical one of not removing their hats in court. Yet the six months they suffered in Doomsdale (below) was the worst imprisonment Fox was to endure, his suffering being intensified by the indescribable filth of the prison. Fox describes the horror of it both in his journal and more fully in the pamphlets he afterwards published.

Fox thought the inhabitants “dark and darkened” and in vain did he protest against the vanity and love of sport in the town, seen displayed on the bowling green adjacent to the prison. Sewel, Fox’s biographer. describing the gaoler – a former criminal. writes: “It was not at all strange then, that the prisoners suffered most grievously from such a wicked crew, but it was more to be wondered at that Colonel Bennet (t), a Baptist Teacher, having purchased the gaol and the lands belonging to the Castle, had there placed this head gaoler.” Bennett was obviously impatient of the Quakers, although he ultimately released the three men unconditionally on September 9th, 1566, without payment of the fees to their brutal gaoler, “and so as innocently they caame out of prison, as innocently they were put in.” Fox left behind him in Launceston a “Little remnant of friends that has been raised up here while he was in prison, whom he visited when he returned to town a very short while after his liberation.” The subsequent story of the group is not known, but it seems that it did not survive for long.

Cromwells Visit

Colonel Robert Bennett, to whom they referred, was a local man of considerable prominence. He was born at Hexworthy, Lawhitton, and his father, Richard Bennett, who died when Robert was only fifteen, had been a Counsellor-at-law. Robert Bennett was named in 1643 as commanding 1,200 foot and 300 horsemen from Cornwall at Torrington, but his effort there to surprise Colonel Digby was defeated. In 164 Cromwell is reputed to have spent three days with Bennett at Hexworthy-which is quite possible, since Bennett was one of Crowell’s trusted advisors. 1649 sees him defending the trial of the King, justifying it before Truro Quarter Session by “an appeal to scripture, law, history and reason.”

In 1653 he was a member of the Council of State of thirteen, and the next year he was one of Cornwall’s Members of Parliament. In local life he was an Alderman and a Justice of the Peace. While his civil and military career is fairly well known, nothing has yet been discovered to shed any light on Fox’s description of him as a Baptist. Hitherto there is no trace of baptist influence in this part of Cornwall. Possibly there were a few Anabaptists and Brownists in Cornwall, but there is no evidence of an Anabaptist Congregation in Cornwall such as the community in Tiverton in 1626. On the other hand the Civil War had brought many new influences in its train. Dr. Whitley emphasised the part the Army played in spreading Baptist Doctrine. “Many a garrison town heard preaching by Baptist officers, to the scandal of the clergy and even of their own commanders….The Army was mobile, and it is instructive to study the rise of Baptist Churches where regiments were quartered.”

But in Launceston, in spite of Bennett, no church seemed to have been formed, and it would seem that in this small community there was but little scope for Baptists where the Presbyterian forces were strongly entrenched. The Restoration deprived Bennett of his seat in Parliament. He retired to Hexworthy until his death on July 6th, 1683, at the age of seventy-nine. His finely carved slate tombstone was found in the 1950’s in a neglected part of Lawhitton Churchyard, and is now fixed to the South Wall of the Church interior. Gewen on the other hand was in favour, and was replaced in his office under the Duchy of Cornwall, but shortly afterwards died.

The Restoration

With the Restoration came other changes. William Oliver, the minister of St. Mary’s Parish Church, had been outstanding in Presbyterian circles, as the frequency of his name in the minutes of the Cornwall “Classic” suggests. But with the Act of Uniformity Oliver was ejected, though he remained active in the district. It seems as if he continued to gather a congregation around him, preaching in unlicensed places. In an isolated community such as Launceston the penalties for this might be defied if the local authorities were sympathetic, as indeed they might have been. The Secretary of State to Charles II was Sir William Morrice, another Presbyterian, who lived in the nearby parish of Werrington, and through his influence a pension was secured for the support of Oliver and his family. Yet there is a hint of their suffering given in the parish records, for William, son of William Oliver (born on July 31, 1658), was buried on April 29, 1664 2in the little yard.” Oliver is still described in the entry as “Clarke” although afterwards this was partly deleted.

A few years later, on 22nd April, 1672, John Hicks, who was a Puritan Mayor during the time of the Commonwealth, applied for a license for “William Oliver, of Dutson, near Launceston, Presbyterian” and an indulgence had already been granted to him. Oliver had in fact taken the “Oxford Oath” in 1666, and thus escaped the penalties of the Five Mile Act which fell on those unwilling to declare that they abhorred resistance to the King and would not seek an alteration in the government of Church or State. Soon after this a census showed that there were thirteen Nonconformists in the town, as well as some Quakers who had been in the town gaol for many years. Oliver kept a school in the town, bred many good scholars, and died a Lay Conformist.

Subsequently, a tablet was placed in the South-East corner of the Church from which he had been ejected to commemorate him.

(“William Oliver, Master of Arts, Sometime fellow of Exeter College, Oxford, and not long sinnce Pastor of this church, but recently Master of the Royal Free School in this place, sweating in the dust of which he died of consumption.”)

The death of Oliver did not mean the end of Puritan influence. The Parish Register of St. Thomas the Apostle, Launceston, has some entries concerning a Robert Gill. In January 1695, he buried his wife Jane, but remarried in October of the following year, and on January 12th, 1697, “Robert Gill and Mary, his wife, has a daughter baptised Mary by a dissenting minister”-the last four words in a later hand. A similar entry on January 22, 1699, records the baptism of their son, Robert, “by a dissenting minister.”

Larkham’s Grandson

Who this minister was is not known, although in the late 1950’s records of the Cockermouth Church had shown that in 1694, thirteen years after Oliver’s death, there was a church in Launceston whose minister was Deliverance Larkham. Deliverance Larkham was grandson of Thomas Larkham, Vicar of Tavistock (from 1648 until ejected in 1660) and first minister of the Tavistock Congregational Church. George, Thomas Larkham’s son, was first minister of the Congregational Church at Cockermouth which Thomas Larkham had founded while still holding the living at Tavistock, Deliverance, George’s son, was born there in 1658. Sent to London for better education in 1667, he was received into the Cockermouth church in 1681 which in 1694 called him as assistant for his now ageing father. But on July 22 “The Pastor received a letter from the people at Launceston which manifested they had chosen him caalled by them, namely, Mr. Deliverance Larkham, for their Pastor. Wherefore they desired to keep with them.” The following year Larkham promised to come to Cockermouth, but finally changed his plan, and left Launceston for Lancaster.

The Presbyterian church in Launceston was again without a minister in 1705, for a copy of a letter dated November 5th of that year is recorded in the Church Book (begun in 1790). The copy appears to have been made about 1830:

“Revd. Sir, We whose names are under-written, knowing that you are not ignorant of our cause. And how calamitous it is like to be upon the removal of the Rev. M. Berry, unless some other suitable supply may be obtained, do hereby make it our earnest request to you that you would be pleased to favour us with your presence and Ministerial Labours….”

It is not known whether the unnamed recipient accepted the invitation. M. Berry who was leaving may have been related to either Harry, Benjamin or Henry Berry-all ejected ministers and active Nonconformists in the West. Henry Berry had in fact lived not far away in Torrington from 1690 to 1744, where he died and was buried, having “ministered to a numerous people, but very poor.” The authenticity of the letter, which was signed by forty men, is guaranteed by a number of their names appearing in the local parish registers of the period. The list includes Robert Gill, Edward Bennett and Thomas Oliver.

Edward Bennett was the grandson of Robert Bennett. His father, William, who died in 1704, left £120 to erect “a convenient meeting-house for the ordinary and most common use of entertaining a Congregation of Dissenters from the Church of England, as were commonly called Presbyterian.” The land was purchased for this in 1707, and the church built and opened in 1712. This was the site (The Congregational Church in Castle Street below) that had the Union church.

Hard and Coarse

Once the meeting-house was built, the church grew under the ministry of Rev. Michael Martin, who had been ordained by the Exeter Presbyterian Assembly on June 28th, 1694 and was financially assisted while in Launceston by an annual grant of £6 from the Presbyterian Fund in London. Within a few years the Congregation included 130 ‘hearers’ amongst whom were five county and fiver borough voters, while the actual membership of the church consisted of three gentlemen, fourteen tradesmen, five yeomen and ten labourers. Yet the life of the church could not have been easy, even though there were neighbouring churches at Tavistock, Okehampton and Holsworthy. The town was strongly Tory, and Nonconformists did not flourish in such an atmosphere. There was much to harden and coarsen the inhabitants of the town; criminals were still publicly hung on the Castle Green, only 100 yards from the church, while for lesser offences women as well as men were flogged through the streets behind a cart.

Martin, who later left for Lympstone, was succeeded by Rev. William Tucker. He, however, removed to St. Ives in 1728, and Martin then returned to Launceston, remaining there until his death in 1745. In his will he left £50 to the church, and a further £ 10 for a neighbouring church at Hatherleigh. But the cause was declining; no minister was appointed to succeed him, although a Mr. George Castle occasionally preached. Eventually the meeting-house was closed, and Richard Coffin-heir of Edward Bennett, sold the property to a local clothier. So it was that the early Presbyterian Church, whose roots are to be sought in the Puritanism active in Cornwall in the early 17th century, and which from this obscure beginning became a separate reality by the leadership of William Oliver after the events of 1662, found strength to survive the first hazards of its career, securing its own building, partly because of the help of the Bennett family with its Baptist sympathies. Yet, once the first perils had been passed, decline set in. Was Oliver, the founder, at fault, for having courage, yet not courage sufficient to go striving for reforms as others did? Or was the church too prone after all to follow the fashions of the day? Did some wooing voice succeed in undermining their dissent? Or were the church leaders led to conform by hope of their securing public office in this ancient borough, then the capital town of Cornwall? All we know is the church suffered the fate of others at this time, and its life seemed ingloriously to have ended.

But by now a fresh wind was blowing in the religious life of the land. In 1743, Wesley was evangelising in Cornwall and George Whitefield in Devon. Wesley’s first visit to Launceston was in 1747, and he paid a number of visits subsequently. By the time of his visit in 1789 a chapel had been built which on that particular day was too small to accommodate the congregation which came to hear him. Yet despite the astonishing growth of Methodism in Cornwall it did not completely take the place of the lapsed Presbyterian churches, and in Launceston itself the heritage of the earlier Dissenters was not to be lost to their more direct heirs. In 1777 Sir William Trelawney gave an address in Launceston and a certain William Derry was seriously impressed. Yet not in him alone was God’s Spirit at work. The preface to the Congregational Church Book, dated June 6th, 1790, begins:

“The Cause of Religion in this Town and Neighbourhood in the dissenting line had declined and ceased for a considerable number of years previous to the year 1775. About this period it pleased God to bless a Mr. John Saltren of this Town with a Religious Concern; very soon did he meet with a pious friend in the neighbouring borough of Newport, when they met together form time to time for the purpose of Social prayer and religious conversation. In a short space of time after this, a few others, being also under God wrought upon by means of the Spiritual instruction received by means of the persons mentioned, they formed themselves into a religious society, and appointed stated times for their devotions.”

So it was that the little group grew; “Then “Mr. Saltren began to excercise his talents more publicly and openly, by preaching the Word of God to all who chose to attend. Hearers at this time began to increase in number.” So a larger kitchen had to be used to accommodate them, and soon after they had to move again to “the Great House, situate at the foot of St. Thomas Hill.” John Saltren left Launceston for Taunton and then Bridport, but his brother William succeeded him. In 1788 the old meeting-house at Castle Street was purchased and “was entirely refitted, or rather rebuilt, as it had been planned out for a dwelling house….The expense of reconverting it, including the purchase money, amounted to the sum of £380. This house was opened for religious worship on Thursday 18th of September, 1788.”

Baptist Minority

At this period we find for the first time precise information about Baptists in Launceston. There is no doubt that the cottage meeting at Newport, from which the Independent Church had grown, had contained a minority if Baptists. They now decided that the time had come for them to form their own separate church. They were never numerous, and events proved the town was too small and Methodism was to become too strong to allow both the Baptist and Independent churches to thrive. Yet, although overshadowed by the sturdy growth of the Independent church, for twenty-one years a small Baptist Church met regularly for worship, a church which is not without its claim to fame. Its story can be partially reconstructed from it minute book.

The leading figure of the church was Thomas Eyre, in whose hand the entire minute book seems to have been written. He was engaged in the wool, skin, and combing trades, and was of sufficient local prominence to be one of eleven local householders who in January 1832 were active in seeking reform in local Parliamentary representation. His brother, John Eyre, became an Anglican priest, after graduating at Oxford, and then joined the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion. Robbins, in his book, states that John Eyre was at first associated with William Saltren; his influence within the Baptist Church is evident from the careful formulation of their confession of faith, set out in twenty-seven numbered paragraphs which faithfully reflect contemporary Calvinism.

Eleven signatories-eight men and three women, appear beneath the “Solemn Agreement entered into by all who join this Church commonly called Baptists.” On Thursday, March 24th, 1791, they had opened their meeting-house in Southgate Street. Alteration to the premises had cost nearly £49; there is no record that Thomas Eyre was ever repaid this sum. Then on the next day, Friday, at 8 p.m. six of the men were “put into a proper Church State by the Revd. Hugh Giles and gave each other the Right Hand of Fellowship. The following Sunday three more members were received on their behalf by Revd. Giles. who administered the Lord’s Supper.”

Chings Stores

So the Baptist Church in Launceston was born; a small yet sturdy infant, meeting in a large room at the back of what was then “Ching’s Stores,” for which their accounts show they paid £5 5s. a year rent, having a twenty-one year lease of the room. Their accounts also show that another minister was present on March 25th, a Revd. J. Wilkinson, whose expenses were 5s., compared with 7s. 6d. for Hugh Giles. Not lacking in zeal, at a church meeting on March 31st they “agreed to continue at every Thursday Month at Evening. And Stated Times of public worship by Sabbath Days-Eleven o’clock in the morning-Three o’clock afternoon-and Six o’clock in the Evening-and that all meetings be ended at Nine o’clock in the evening and not later.”The next month a member was added by baptism, the service being conducted by Rev. William Smith, when in addition a man from Tavistock was baptised. The Church Meeting which had authorised the baptism had also made Thomas Eyre their first, and only, deacon and elder.

At the close of April the Church Meeting passed a resolution concerning another of its members, Jacob Grigg “…we also believe that he is possessed of spiritual and natural gifts, as we have frequently heard him with pleasure and profit dispence the Word of God among us…We therefore call him to preach the Gospel here amongst us, or whenever a door may be opened in Providence for that purpose…”

Baptised in Mill Stream

In May 1792 Isaiah Birt of Plymouth and Robert Redding of Chacewater visited the church. Birt baptised Thomas Eyre together with William Lenn (another foundation member) and his wife “who desire to bless God for what they experienced of his prescence in that holy Institution.” The baptism took place in the Mill Stream at the foot of Ridgegrove Hill. Later in the month Richard Lenn was baptised by Birt – but at Plymouth. (It is interesting to note that these foundation members were only subsequently baptised).

A year later, in May, 1793, the church considered Jacob Grigg’s request “to go to the Academy at Bristol for a Term of one year for Instruction, and then to return for to reside among us again in preaching the Word as usual.” To this he was commended through the agency of Isaiah Birt. Already in January of this year Grigg had been registered as the teacher of the church, But at Bristol Grigg found his horizons widened, and in consequence did not returne to Launceston but, being accepted by the Baptist Missionary Society, sailed in 1795 for Sierra Leonne.

The church never recovered from the loss of Grigg. In 1796, in their letter to the Association, which met that year at Exeter, they describe themselves as “remaining obscure from our Brethren and Fathers in Christ.” The only remaining entry of consequence in the minutes is the copy of the letter to the Association dated 1797. After a florid introduction it continues:- “And we beseech you, that…you would have a kind remembrance of us, two or three poor members of Christ at Launceston; for the cause of Christ is very low with us as to our number, and we are almost weary of waiting the Lord’s Coming to make bare his Arm, as we have no addition to our Little Society, and are at a distance from the Ministers of Christ visiting us: Yet we bless God that we are kept together in the Love of the Lord Jesus, and that we frequently find His presence with us, which still encourages us to keep open the doors of the Lord’s House…”

So the handful of members struggled on. In 1811 the church was still listed in the Baptist Magazine, but the next year the lease at Southgate ended, and after this, the church ceased to exist as an organised body. One or two of its members of the Independent Church, where undoubtedly more continued to worship. Yet without a building, and without regular Baptist fellowship, a few remained loyal to their Baptist principles, so that a generation later another church was founded with greater success.

Castle Street Progress

In the meantime a very different story was being enacted at Castle Street, where the Independent Church was making great progress. After the Independent Church had been worshipping in the Castle Street meeting-house for a little less than two years, they felt themselves strong enough to draw up a constitution and a set of rules, which was adopted and signed by Twenty-seven foundation members. Three days later, on Wednesday, June 9th, 1790, William Saltren was ordained to the Christian ministry, with representatives present from Plymouth, Bideford, Kingsbridge, Appledore, Bridport, Honiton and London. The srvice began at 10:30 a.m. and continued until 2:30 p.m. A service the same evening was somewhat shorter. According to a manuscript of Robert Pearce, Junior, the charge to the minister was preached by Rev. Mr. Lavington, of Bideford. On the first day of the next month two deacons were chosen, and three new members admitted. The following Sunday the Lord’s Supper was observed, twenty-six people being present, and the collection for the poor amounted to 8s. 8d. which was immediately distributed to four members. For many years the practice continued of holding a Church Meeting on alternate months, and always the Lord’s Supper was celebrated the following Sunday.

During the five years of William Saltren’s ministry the membership grew from twenty-seven to forty-two. One of these members, June Hurden, was received on a recommendation from “Revd. Mr. Birt, minister of a Baptist Church at Plymouth Dock (modern day Devonport).” We are left to speculate why she joined the Independent Church, and not the Baptist, and wonder of on the day before this meeting approved of her she witnessed the local baptismal service which Birt conducted. It certainly suggests that as in the previous days of the Newport Meeting, there was still tolerance of the Baptist position among the Independents.

Saltren died on Saturday, April 18th, 1795, aged forty, and a bachelor. Soon after, three more deacons were chosen, and in August it was resolved “to engage the Revd. Jonas Lewis, late from Wincanton, Som. until Ladyday, 1796, at 20/- a week.” When this probationary period was ended he was called to the pastorate on a permanent basis, and although dissuaded by an anonymous letter, he accepted the call when it was unanimously repeated. The same year saw the first missionary interest, and a collection in June, 1796 raised £14 for this purpose. But Lewis pastorate was short. The Church Book has been mutilated, so that the record is deficient, but soon after May, 1798, Lewis left the church. It was suggested that there was a personal difficulty with the congregation. Although the church was soon to prosper, this was but the first time such an event was to take place.

Outstanding Pastor

The turn of the century saw the beginning of an outstanding pastorate. On June 29th, 1800, Richard Cope, then senior student at Hoxton Academy and afterwards a Doctor of Law, first preached at Launceston. His stay was prolonged for two months, then for a year, when he was invited to the pastorate at a stipend of £60 a year. This invitation he accepted, and was ordained on October 21st, 1801, remaining at Launceston until June 1820, when he left “to fill a more important situation in the church of God as tutor to an academy in Ireland.” Cope was a most enterprising man, a keen social reformer, and active in seeking the abolition of the Slave Trade. (He published a sermon on this theme in 1807 that he had preached on May Day). Due to his initiative a Sunday School was founded in 1800, during his first probationary year. It was one of the earliest in the county, although at Falmouth such work had begun earlier still. Within a generation the Sunday School had grown to a Union embracing seven other schools in the neighbouring country areas. The church grew so that it was necessary to erect another gallery within three years. But soon after the work was completed, on Christmas Day – a Sunday – while the church was at worship “a storm of wind seized the roof with such violence as to damage it very considerably” while a few weeks later another storm blew a chimney stack down, causing further damage so that “a great part of the timber work was broken…the rains that followed brought down a considerable portion of the plastering and rendered the Meeting almost unfit for worship. However, a subscription list was opened which attracted some sixty-six donors from all local parties and creeds. Nearly £100 was raised, which almost paid for the new gallery, as well as the roof.

Continued growth required further enlargement in 1809 – costing over £300 – and in 1815 another gallery was erected, this time behind the pulpit. When Dr. Cope left the church his stipend had been increased from the original £60 a year to £150; he had admitted 104 new members into the church, including two members of the Lenn family, two of the Eyre family, and a Grigg, all families with Baptist connections. He had been head-master pf a local school during part of his pastorate. Subsequently he ministered at Wakefiled and Penryn, where he died in 1856 at the age of eighty.

The following year Alexander Good began a new pastorate, during which the church building was again completely repaired, its last major alteration. In 1824 Revd. J. Barfitt succeeded Good; nothing is disclosed concerning the end of his ministry. Barfitt ministered for twelve years, during which time the system of pew rents was revised, the best seats costing 8s. per annum (or £3 3s. a pew) while others could be had for 6s. or 4s.

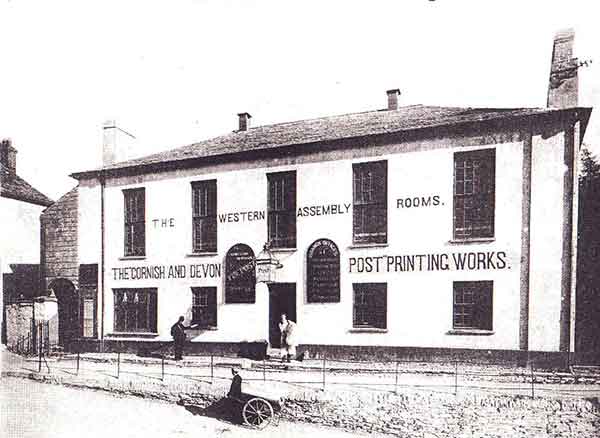

John Horsey, of Western College, almost immediately followed Barfitt in 1836 – another notable ministry which continued for thirty years. During his first year’s ministry an interesting minute is recorded:- “Persons offering satisfactory evidence of conversion to God shall be considered eligible to all privileges of Church Communion, not-withstanding any difference of opinion on the subject of baptism and other points now expected.” New members for that year included a Mr. and Mrs. Pattison. In August, 1830, Professor Pattison of the Northfield Bible Institute of America, on a visit to Launceston, stated that his grandfather had been a member of the early Southgate Baptist Church in Launceston, and subsequently moved to London, becoming a member and later a deacon at the Bloomsbury Baptist Church. Here again is evidence that the Independent Church continued to accept the members of the defunct Baptist Church into its fellowship and that the scanty records of the baptist Church do not show the complete extent of its life. Pattison seems to have been a man of some status in the town, for he was a solicitor who became the first president of the Mechanics and General Institute, founded in 1847. Probably in 1850, due to influence of the Castle Street Church, the village chapel at Greystone Bridge was opened. This was later adopted by the Baptists. Although Horsey’s ministry was of such duration, all was not well. There is no entry in the church book for the last ten years of it. In 1865 he resigned, but then withdrew his resignation. After the subsequent discussion in a Church Meeting which was far from happy, the greater part of the congregation split, and continued to worship in the Western Subscription Rooms (a public hall below), until after the end of Horsey’s ministry.

Horsey resigned the pastorate in 1866 “after passing through a severe trial in respect to himself and the church.” At the close of his ministry he was able to persuade the church to abandon the old Presbyterian custom which had prevailed until then of sitting in singing and standing in prayer.

T. E. M. Edwards began a short pastorate in 1867, which he resigned for health reasons two years later, but in which he had ministered to the reunited church, and seen the membership grow from 57 to 97, a growth which was reflected in the considerably larger, but unrecorded, number of “seat-holders,” and the publication of the first Church Manual in 1868. The church was sufficiently strong to entertain the Association for their two-day meetings in April, 1869. Also during this pastorate the old box pulpit was removed, and another pulpit installed, while the project for a new vestry was accepted.

Lifton Church

Thomas Jackson, B. A., from New College, became the pastor in 1870, and at his ordination the Baptist Minister from the church at Lifton was present. This Lifton Church, opened in 1850, partly fostered the revived Baptist Church in Launceston, founded in 1876, Jackson’s pastorate was unhappy; after two years he tendered his resignation stating he felt he had lost the confidence of some of the members, and his insecurity was made worse by the inadequate stipend (£140 per annum) and lack of a house, as well as by his own indifferent health. After a stormy meeting, when no less than 248 members of the congregation had petitioned him to remain, despite the deacons opposition, all seemed well. But by July of the following year Jackson brought the deacons continued opposition into the open. Six sermons which he had submitted to two distinguished arbitrators, Dr. Allen and Professor Charlton, were pronounced orthodox. When these findings were made public however, some of the deacons continued to remain hostile. Jackson thereupon not only resigned, but left the ministry, adopting medicine as a profession with good success. Within ten years of his settling in Croydon he was elected to the Town Council.

Jease Bamford succeeded him in 1874, and began a pastorate of nineteen years which marked the peak of the church’s life. The membership grew swiftly; in March 1877 no less than twenty names of prospective church members were proposed. The same year the organ was enlarged, and soon afterwards the fine block of Sunday School buildings which face the church was erected (below). It is of interest to note that this period was also one of general prosperity in the town, marked especially by the building of several new streets of substantially built houses.

Langore and Polyphant

In 1891 a Men’s Bible Class was started – the origin of the Launceston Brotherhood – while the Church Book records a discussion on means of improving both the attendance of young people at the church services and the general attendance at the weeknight meeting. But the little village at Langore, whose origin is unrecorded, so declined that this time of prosperity in the town the trustees were compelled to close and sell the property to pay off the accumulated debt on the church. In 1894, Bamford was followed by William Miles. His was another happy ministry often recalled by older members. At this time the manse was purchased, and better incandescwnt gas lighting was installed in the church. The long-hoped-for vestry was built and a new heating system installed. Some of this work was stimulated by the 20th Century Fund. In 1901, the village church at Polyphant was sold to Wesleyan Trustees for the sum of £10. At the turn of the century, therefore, we find the church apparently vigorous and strong, with an evening congregation which frequently filled the building which seated five hundred.

The re-established Baptists

With the Baptist Church at Southgate ceasing to exist as an organised body in 1812, its few stalwarts continued to be active in the district, and the Baptist witness was maintained by their preaching. In 1849, in the village of South Petherwin, a Baptist church was founded (below left). Very little is known of this church, and so far no trace of its records or minutes, if any were kept, has come to light. In the following year another church was formed, at Lifton, on the main road to Exeter.

This church had at least one immediate link with the former church at Launceston, since Dorothy Gould, who with her husband, John, were prominent in its life, was a daughter of the Lenn family. William Lenn had been a foundation member of the first Launceston Church with his son, Richard. A shoemaker by trade, Richard was well known as a preacher in the district, and would walk miles every Sunday to serve the village churches. He had some fame as a local poet, and wrote verses on topical events for the local newspaper, especially about feuds that then existed between the churches and the chapels. He did not die before 1874, and provides at least one certain link between the earlier church and the churches at South Petherwin and Lifton. Mr. Stanley Gould, who became secretary of Mutley Baptist Church, Plymouth, comes of this stock and having been president of the Association in 1943-44, gave sure proof that the family still keeps to its tradition.

Lifton, Polyphant, South Petherwin.

The church at Lifton decided to build a chapel which was completed in 1851 and seated 150. From the start the church had an open membership, but its trust emphatically stated that the minister must preach “Believers baptism, and no other.” The following year saw the visit of “Mr. Wheeler to Launceston, formerly a missionary in West Africa.” Was there any recollection then, we wonder, of Jacob Grigg who had left Launceston for West Africa fifty years earlier? “Mr. Wheeler” was in fact J. A. Wheeler who went out to the Cameroons under the Baptist Missionary Society in 1850, but returned in 1852. Wheeler remained at Lifton, becoming its first pastor.

The minutes of the Lifton Church show that W. D. Hanson was also active in its life. He was later the squire of Polyphant, and was instrumental in forming a Baptist cause in that village in 1872. This Church was again short-lived, and little information about it survives. Mr. W. R. Pattison was another leading personality, whose connection with the former Launceston Church has already been noticed. He provides another link between the two churches. Another active Baptist was a Mr. Peter, of South Petherwin, who was frequently associated with activities at Lifton. An interesting minute records that on Good Friday, 1893, a Baptismal Service was held, and one of the speakers at the evening meeting was R. Lenn, of Launceston. At the Church Anniversary in the same year the congregation exceeded 200. In 1855, there was some discussion about raising the pastor’s stipend, and a suggestion made that the Church at South Petherwin would help, but the idea fell through. In 1860, the membership had passed forty; the tenth Anniversary was celebrated, the visiting preacher being T. H. Pattison of Regent’s Park College – a son of W. R. Pattison. He was later to become Professor T. Harwood Pattison, D. D., of Rochester Seminary, U. S. A., who gave the Ridley lectures in his old college in 1900, a few years before his death.

Greystone and Sourton

The following year records, amongst other baptisms, one from Greystone Bridge – the first record of Baptists there in 1862, the Congregational Church at Launceston, which had hitherto been responsible for this small church, made an arrangement with the Lifton Church to share responsibility for it. The Church, now closed, held a service once every Sunday; its congregation was small – rarely exceeding a dozen, often half that number. But there was an atmosphere of sanctity in the small building so delightfully situated on the banks of the Tamar nestling under a wooded hillside. Its older members could recall still earlier years, and the baptisms in the river close by. From 1928 it was under Baptist Trustees.

In 1863, a preachers’ plan was drawn up to embrace Lifton, Greystone, Bulford (of which we have no knowledge) and South Petherwin. The following year a church was established at Sourton; this church standing on the borders of Dartmoor, looked however to the Baptist church at Okehampton for its main support. In the record of baptisms we find names of two Launceston ladies, both of whom were at the time in membership at the Independent Church at Castle Street. 1868 saw the baptism of Henry Fitze a member of a long standing Baptist family. Now there come some changes in the pastorate; the year 1869 sees Thomas Honyer inducted to the pastorate “after labouring as an evangelist in connection with the church for more than three years.” He left in 1872, and was succeeded for six months only, by John Hier. In 1874, George Parker became minister, and with his coming the church discovered new vitality. He came from Croscombe, Somerset, and was introduced to the church by William Haines, of Spurgeon’s College. The next year sees the first reference to services at Portgate, and amongst others baptised is the new pastor’s second son.

Portgate

The Portgate church trust was dated February, 1864 – ten years before this, and it was never legally enrolled. It was built by Mrs. Thomasine Smale largely for her own use, and by her will she left most of her estate for its benefit. The will was contested by her family, but the Devon Baptist Association proved the case, and then accepted a sum of £660 captital to provide “Smale’s Bequest,” the income from which was for the benefit of the Baptist Minister of Lifton or Launceston. The church itself has long ago ceased to exist, and the derelict building with its small graveyard was legally disposed of, not without difficulty, in 1930. Parker’s entry in the Lifton Minute book for March 26th, 1876 reads “Comd. preaching the Gospel in the Room for many years occupied by the ‘Bretheren’ in Duke Street, Launceston. We had nine in the morning and twenty-six in the evening….We hope to continue the service here, and to work it in connection with Lifton.” The services did in fact continue, and the church at South Petherwin moved to Launceston selling their building there for £75 in 1890. By May the cause at Launceston was sufficiently established for a permanent agreement to be drawn up with the owner of the hall in Duke’s Lane (between Northgate Street and Tower Street); it was made over the signatures of George Parker, Richard Peter, Henry Gardiner (two men outstanding in the early days of the reconstituted chruch), James Palmer, R. F. Bray and C. Vesey. The rent was £5 5s. a year, payable quarterly, for the use of the room on Sundays and one weeknight. In July there were nine baptisms at Lifton, with 300 present; Parker also records “Mr. Spurgeon has sent a young man, a Mr. J. Wilson, to preach at Launceston and try to establish a Baptist Church there. He has continued his work with great encouragement. Several souls have been saved and baptised on a profession of their faith at South Petherwin.”

John Wilson had first preached on Sunday, May 7th, and the following Tuesday his ministry was recognised when Rev. John Aldis, of George Street, Plymouth, was the special preacher. Presiding over the evening meeting was Squire Hanson. The church was formally constituted later in the year – on October 12th, 1876, John Wilson being unanimously elected as its first pastor, and Messrs. Pode and Gardiner the first deacons. The church consisted of thirty-two members. Soon afterwards, Richard Peter was also appointed as a deacon .

The next twelve months saw the church established, but later in the year, after fifteen months work, John Wilson (who had already spent a short period at Chiswick) left for Woolwich, where he was to spend the remainder of his life. 1877 also saw the Lifton church purchase a Manse.

Thorn Cross

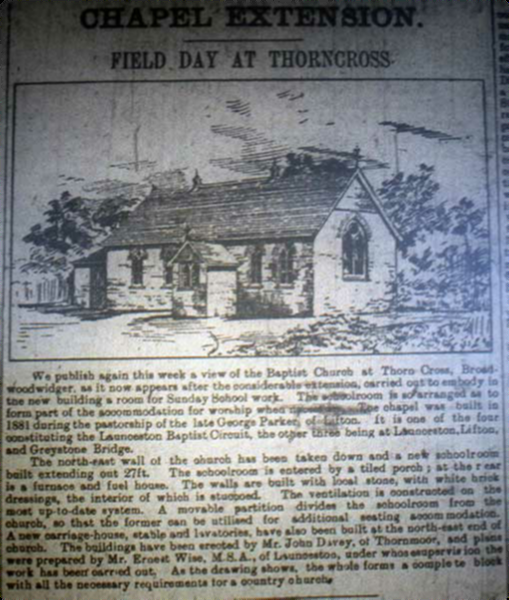

Wilson was followed at Launceston for a few months ny A. E. Johnson – another of Mr. Spurgeon’s early students, but after he had left, Parker, at Lifton, accepted the oversight of the church, and in December, 1878, thechurches at Lifton, Sourton, and Launceston, agreed formally to unite under the one pastor. Parker’s initiative was not yet spent. Having secured the formation of the new church at Launceston, he looked for other opportunities and found one at Thorn Cross, three miles from Lifton and five miles from Launceston, an area of scattered farmsteads and cottages that would not even comprise a hamlet, but yet together making a sizeable community. The first record of any work here comes in 1879, when Parker started a cottage meeting. Within two years land had been purchased for a Church building; in June, three months later, the first stone was laid of a building to be completed that same year – much of the work being done by voluntary labour and by farmers giving free carriage for building materials. In 1884 it was free from debt, the Association Chapel Case having contributed £100 towards it. At Sourton, too, the work was growing, and in 1882 a chapel was erected. This also was cleared from debt by 1884, so that Parker and the church at Lifton were responsible for two new buildings within two years, both of which were paid for by the end of the third.

After a ministry of eleven years, Parker left in 1885 to go to Buckinghamshire. When he left, the Sourton church turned to Okehampton for oversight, but Lifton and Launceston continued to work together with the smaller churches at Thorn Cross and Greystone Bridge.

Western Road

In Sir Alfred Robbins‘ book on Launceston it is stated in respect of the Launceston Baptist Church that “for some years up to a recent date there were no regular services” Robbins wrote in 1883. If he meant that services were irregular between 1876 and 1883, this incorrect for Mrs. John Fitze, a foundation member, was able to assert categorically that there was no such break. He may instead have meant that some services were held periodically btween the closing of the Southgate church in 1812 and the opening of the new church in 1876, and if so (and we have no other proof of it) it means again that the Baptists were more active in Launceston than their records suggest.

The pastorate at Lifton was filled again in the following year, 1886, by the Revd. Franklyn Owen, who came from Bristol College. He resigned a year later and was succeeded by George Keen, a colporteur engaged in the district, who undertook the pastoral oversight of the group of churches. In 1891, the ministry of the Revd. H. Smart began – with the minister no longer resident at Lifton, but at Launceston.

The following year the Launceston church left the rented hall they had used hitherto and moved to the new church they had built in Western Road (below). This seated 130, with a basement Sunday School hall. Here the church worshipped during thirty-six years of steady growth until this building was out-grown, and they were established as a spiritual force in the life of the twon. Smart left in 1897, to be followed by C. J. Leal from 1898-1906. A. E. Knight succeeded him in the same year, and in 1908, D. Dighton Bennett B.A., began a ten-year pastorate.

While the work at Launceston was growing, the Lifton church fell on bad days. The village also had its strong Parish Church and a strong Methodist church; the Baptist church found as well that their daughter church at Thorn Cross was drawing considerably from their strength; the congregations declined to a handful, and it was at last decided to close the church. The final service was held on Whitsunday, 1916, and in 1920, the building and its furniture was sold for about £400.

Bennett had been succeeded in 1919 by William Bonser and in turn he was followed by E. P. Thorn in 1922. This pastorate proved to be a short one, and Bonser returned for a second pastorate from 1924-1927, before he finally retired. The church by now was seeking better accommodation than the small church building in Western Road offered, and at the time that they called H. W. Hughes (then a student at Spurgeon’s College) to the pastorate in 1927, they also embarked on an ambitious extension programme. The old church building was sold, and subsequently converted into showrooms for the local Electricity Authority.

Madford House

A large old house – Madford House, standing in its own grounds in the centre of the town – was purchased, and its newer wing was converted into a church by rebuilding an outside wall to enclose a large area. The rest of the building was used for various church rooms, and as a Manse. The scheme cost about £4,000 but a portion of this was realised by the sale of the old church and by the subsequent sale of part of the gardens of Madford House.

The project was a splendid venture, although the church did not at the time realise how expensive maintenance of the property would become. Most of the house had been built early in the 17th century, and it was said to be the first house built outside the old, town wall, and to have accommodated Charles II when he was resident in Cornwall in 1645, being then Prince of Wales. When H. W. Hughes was succeeded by H. J. Harcup, most of the debt had been liquidated. He remained until 1945, being towards the end of his pastorate simultaneously pastor of the Congregational Church, with whom union was subsequently effected.

Returning to that church, in 1904, E. B. Rawcliffe began a ministry, but it lasted only two and a half years. Soon afterwards a new organ was installed, built by Wadsworth brothers at a cost of £458, and hydraulically blown. The Carnegie Trust contributed £125 towards the instrument. It was considered the best two-manual instrument in the district. In 1907, Thomas Bowen began a ministry which continued till 1911. The first signs of the gathering clouds are now seen. The church faced a serious financial deficit in 1909, and at the annual church meeting the following year, Bowen “made reference of the evidence of the lack of spirituality in the church.” Revision brought the church roll from 111 to 77, and when Bowen left he spoke of his ministry as being “exceptionally brief and quiet as exceptionally barren in visible results.”

Theological Differences

1912 saw the church celebrate its bi-centenary (from the Presbyterian foundation in 1712), and in the following year, F. J. Sloper began a ministry which would have been briefer had he been physically fit enough to have joined the Army when war was declared. There were theological differences between him and part of the congregation; not a few of the champions of orthodoxy not only revolted against the “New Theology,” but forsook Free Church principles and turned to the Anglican Church (if to any) for spiritual succour. When F. J. Sloper left in 1919, he returned to the teaching profession and wrote “I have had much happiness and many dissapointments. The fact that the district is not Congregational has made it difficult to replace those that have gone. On the part of some members there is a marked slackness in regard to attendance and enthusiasm; on the other hand, some have been outstanding in their faithfulness and devotion.”

In 1920 began the pastorate of C. Sheppard Gibbs. The church membership now stood at about seventy and finances were proving difficult. In 1923 he stated his intention of leaving. That year sees also the end of the old ‘Church Book’ and the minute book which follows it is the entire work of James Treleaven junior, for long the secretary of the church and an outstanding counsellor and philanthropist, whose gracious influence in the town was as beautiful and characteristic as the clear copper-plate of his writing.

In 1924 A. F. Davies began a new pastorate, and soon afterwards the legacy of Hadrian Evans was upheld in court, and the ‘May Evans Trust’ of which £300 invested in 4 per cent. consols, began to benefit the church. F. Bowden followed in the pastorate in 1930, but two years later resigned, having met with considerable criticism for his methods. He returned to London broken in health, and not long afterwards died, leaving a wife and a small child. Augustus Julian, a retired minister succeeded him for a period, but in 1935, in view of the continued decline in membership – now only thrity seven – it was resolved to seek union with the Baptist Church. A scheme for outright union was rejected by both churches in 1936, and A. L. Trudgeon came to the pastorate until 1940. It was then agreed that the church should continue to exist separately, but worship with the Baptists. The agreement was reached after full discussion, and by the decision of an overwheming majority of both churches. On the first Sunday of June, 1940, the congregations united in worship under the ministry of the Baptist minister, H. J. Harcup.

Full Union

The two churches continued to worship in both their buildings using each on alternate Sundays. At the end of the war, in 1945, when H. J. Harcup left for Long Sutton, Lincs., it was agreed to seek full union, and to concentrate the work in the Congregational premises. These, while in a less convenient site in the town, were more commodious than the Baptist church, which lacked any large hall. After a short, temporary, pastorate under W. P. Hodge, K. E. Hyde was called to the pastorate of the uniting churches, and the decisions were implemented. The Madford Church building was leased to the Ministry of Works for office accommodation. The small Walker organ, given by Mutley Baptist Church, Plymouth, was re-erected in Emmanuel Baptist Church, Plymouth, while the pews went to Hele Baptist Church, Torquay. The income derived from the lease of the property was entirely absorbed by the extensive programme of building repairs at Madford and the long-needed renovation at Castle Street.

Subsequently, F. R. Jewry, another Baptist, accepted the pastorate. He was a native of Launceston who married Miss Margaret Gardiner, a daughter of Mr. H. Gardiner, a former Deacon and lay preacher. After ministries in various parts, he returned to Launceston and began his ministry there in 1949, remaining until November, 1953. He was followed in December of that year by the Revd. W. Howard Smith, a Congregational minister whose ministry was greatly appreciated and richly blessed. He remained until failing health and eyesight compelled him to resign at the end of March, 1956. In November, 1956, Revd. R. W. Carr commenced a brief ministry, which terminated the following August, and, owing to the lack of support, it was then decided to close the church in 1957. The Devon and Cornwall Baptist Association and the Devon Congregational Union disposed of the two churches and devoted the money to the establishment of new churches elsewhere. The Greystone Baptist Church closed in 1963 also through the lack of support and the Thorn Cross Baptist church, which had been taken under the supervision of the Halwill group of Baptist Churches at the same time, also later closed.

Why the Decline? (writing in 1964 Revd. Kenneth Hyde attempted to answer this question).

The question will doubtlessly be asked why a church with so fine a tradition as that which formerly worshipped at Castle Street should so seriously decline; although there has been a decline od church life in the nation as a whole, here it is entirely abnormal. While there is no simple answer, several factors can be seen to have been at work. The area is strongly Methodist, and the local parish church is strong. The wide-spread initial success and subsequent failure of the earlier Presbyterian church points the way; so does the remarkable success of the Methodist Revival in Cornwall, which was no doubt helped by the ‘vacuum’ which the lapsed Presbyterian churches had left. The Launceston Church grew under a strong evangelical ministry. A similar ministry saw the growth of the Baptist church; the Congregational church declined most seriously when the ministry was not fully evangelical. But most of all the problem seemed to relate to the fellowship of the church. Out of thirteen pastorates in a hundred years, six ended unhappily, including that of Horsey, who had been minister for thirty years. Edwards, who followed, seemed gald to leave after a short while, and Jackson, the next minister, left in such disgust that he went right out of the ministry. A better period followed with Bamford and Miles, but a generation later the same story was repeated. Soon the decline had set in, short pastorates became the order of the day, the youth work of the church declined – as it always will when the spiritual life of the church is at fault – and the membership was not replenished.

Downinney Foursquare Gospel Party

The former Congregational Chapel and Sunday School were acquired from the Congregational and Baptist Union in 1959 by the Downinney Foursquare Gospel Party. With a major renovation and modernisation of the chapel building needed, the Trustees engaged the firm of Norman Weight Ltd., of Plymouth to carry out the work. The old Sunday School over the higher section of the chapel was removed, whilst completely re-felting and re-nailing slates on the existing roof and re-roofing the higher end of the building were carried out. At the same time the old vestry, which stood under a portion of the old Sunday School, was demolished. The exterior of the building was re-plastered and given a Tyrolean finish. New windows were fitted throughout and the interior walls were all re-plastered and painted. Also a oil-fired central heating system was installed. The pulpit was removed and a speakers platform fitted in its place. A small vestry under the balcony to the left of the platform was also fitted. The tiled baptistry, which was installed to the right of the pulpit when the Baptist and Congregational members united, was retained, as the Foursquare Gospel preached and practised total immersion as the only Scriptural form of Baptism.

The departure from traditional style in the lay-out was expressive of the views of the Trustees, who pointed out that the re-opening of the church was a venture of faith consistent with their conviction that a spiritual revival was imminent. History has proved, they said, that too often the traditional church had been slow to recognise and accept revival when it comes.

For that reason, the church was run on the Free Church lines with directions from no ecclesiastical body, the view being expressed that the Scriptural meaning of ‘the church’ is the body of believers united in a common faith, subject only to the Head of the Church, Christ himself. The venure was motivated by the firm conviction that the Gospel of Jesus Christ was still the power of God unto Salvation and that a personal experience of conversion would replace the present traditional approach. They believed the behaviour of young people, which at that time was causing much public concern, was regarded as an expression of the aching void in the human breast which God alone could satisfy.

While not affiliated in any way, the Foursquare Gospel were supporters of the T. L. Osborn ministry at Plymouth, and believed with him that every believer should be a personal soul-winner. Speaking in 1964, Mr. F. Bate, of Trew Farm, Tresmeer, the then secretary of the the Downinney Foursquare Gospel Mission, said “the beliefs of the Foursquare Gospel are not far removed from those of Primitive Methodism and the early Bible Christians. Emphasis is laid on the need of a personal salvation and on the privilege of Divine healing for the believer.”

They began using the former Congregational Chapel the following year, 1965, and continued to use it until the early 1980’s. The building had proved unsuitable for the groups needs and the congregation began meeting elsewhere in the town, latterly in a classroom at the St Joseph’s School in St Stephen’s Hill. The building was put up for sale by the Trustees, but having lain unused and empty for 30 years its condition deteriorated and in November 2013 it part collapsed. With it being unsafe it was completely demolished and the site is currently up for sale with planning for development.

Visits: 199