.D

From a transcription by Cecil T. Collacott in 1957.

During the 1850s a North Devon farmer bought a little leather-covered pocketbook. For two years he used it as an all-purpose note-book – a sort of intermittent diary, sales and purchase record, whilst a number of its pages contain memoranda varying fro a shopping list to an agreement with a new horseman.

It is remarkable that the little book has survived all these years. To-day the faded entries (often in pencil and hardly legible at times) throw quite a vivid light on the life of a Westcountry farmer in the mid-19th century. Several pages at the beginning of the book are ruled for an account of day labour employed. Three men were paid 10d. per day and younger men received 6d. per day. A number of accounts are in respect of stone-drawing for road repairs. In those days farmers frequently tendered for stone haulage, as they did in fact up to comparatively recent years, to augment their incomes. Farmer Braddon, as we will call him, was paid at the rate of 3s. 6d. per day for the hire of his horse, butt and man. A man loading stones was better off than one home on the farm, for he received 1s. 2d. per day. Drawing stone was very wearing for the butts, and a note was made of the purchase of a butt, at a sale, for £1. At the same time, a set of harrows was bought for 5s. 6d. and a couple of hay-rakes for 1s. 6d. Among other lots were some horse brasses, for those were the days when a special pride was taken in farm horses and their tackle. A keenly competitive spirit existed between horsemen of neighbouring farms as to which should turn out the finest team of horses. Burnished brasses on well-oiled harness flashed in the sun, as brightly-painted waggons, drawn by sleek horses, rolled to and from the market towns with their loads of grain and wool, coal and manure.

SHOPPING LIST.

Farmer Braddon’s shopping lists, when he travelled by pony and to his own market town, make interesting reading, both as to the goods purchased and the prices paid. On one of his visits, he bought 2 lbs. of sugar at 41/2d. per lb., 6 lbs. of rice at 2d. per lb., 1 lb. of figs at 5d. 2 drams of saffron at 4d. per dram, 3 lbs. of candles at 51/2d. per lb., 1 oz. of tobacco for 3d.. We find a cheesecloth, I yard wide, at 6d. on the list, for they made their own cheeses on the farm. They also brewed beer and made their own barm (yeast), so we find hops on his shopping list and a few dozen corks for his bottles. On one occasion he made a note to buy “some cloam for the table.” Cloam was the good old Devonshire for kitchen crockery. He also bought for the local saddler a “half hide for harness (not a thick one), two balls of twine and one ball of tarcord.” Freestone appears on one list, This was used in nearly all the old farmhouses and cottages for whitening the surrounds of the hearths and sometimes the entrances.

EGGS 6d. A DOZEN.

The farmer also had a variety of things to sell when he went to town. He made a note of selling four hares for 6s., a price which indicates that hares were quite a luxury. There is not, by the way, a single reference to rabbits throughout the book. He sold eggs at 6d. per dozen, goose fat at 7d. per lb., a couple of fowls for 2s. 9d., and ducks for 3s. and 3s. 3d. per couple. His customers paid him 11d. per lb. for butter. He had a regular customer for pigeons, which he sent by the “Torrington carrier” to a well-known gentleman of that day, but he does not record the price.

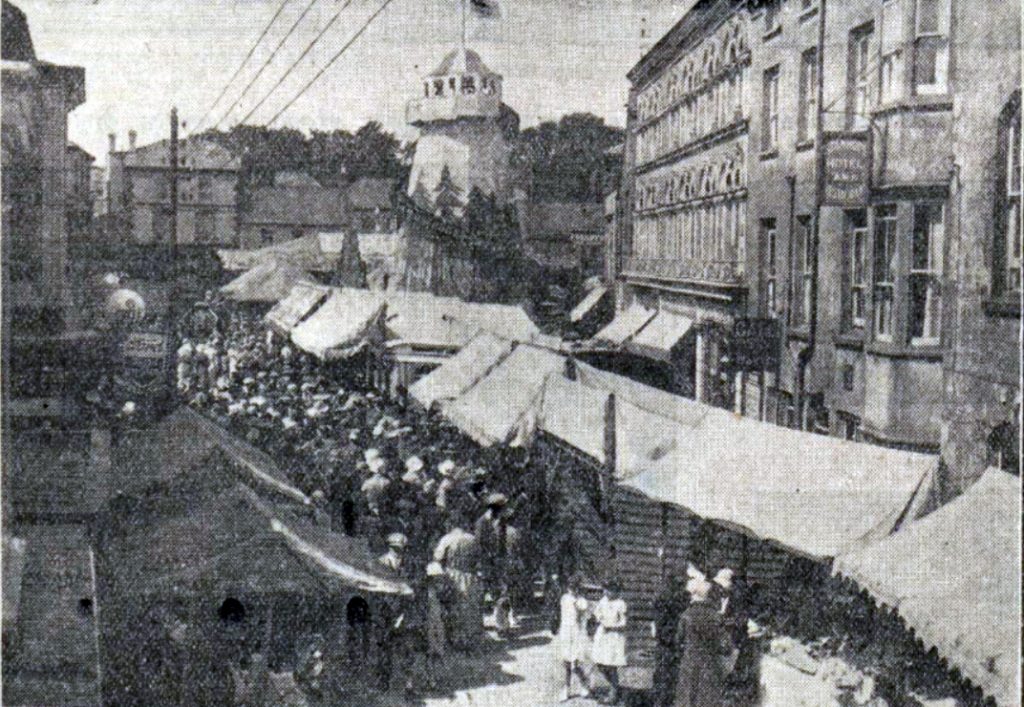

There were no monthly markets as we know today in the mid 19th century, but fairs flourished in several villages. Farmer Braddon sold stock at Bradworthy, Sutcombe, Stratton, and Kilkhampton fairs as well as Holsworthy St. Peter’s Fair (below in 1933), which still survives. Some prices taken at random include: cow and calf, £7 12s. 6d.; four fat steers, £48; fat cow, £11 10s.; fat sheep at 38s. each; calf, 10s.; 4 sheep at £1 15s. 6d. each and 14 at £1 10s. each.

When a new servant was engaged an agreement was drawn up in the little pocketbook. The man or woman signed or made a cross, which was witnessed by a third person. So we find that on the 28th May 1851, the farmer “Agreed with Mary Rudgman to live with us as a head servant from the 31st instant to Lady-day, 1852, for the sum of Three pounds and Ten Shillings for the remainder of the year. She also agrees that if she should be ill any time in the year to allow reasonable charges for the same. The first month on trial on both sides.” On yet another page we read: “Agreed with Samuel Chapple to live with me and drive my horses the remainder part of the year for the sum of Four Pounds and Four Shillings. And he also agrees that if he should be ill any time in the year to allow reasonable charges for the same.”

PARISH RATES.

Our Mr Braddon was evidently one of those responsible for making the parish rate, as there are a few brief notes relating to this. On one page is written: “Rated to poor £98 18s.” and another entry,” Rates not settled.” Amounts due ranged from 111/2d. to 4s 21/2d. There was one amount as low as 51/2d. (part period), whilst in one instance a farmer owed as much as £1 10s. 9d., which must have included a lot of arrears. At that time the village seems to have had a Poor Club, for an account relating to this appears in the book. Names of the more affluent parishioners were recorded, and against them are donations ranging from 7s. 6d. down to 1s.

Only a lifetime and half away are those days in which Farmer Braddon jotted down his notes in the little pocketbook. Yet as we turn over the pages it seems as though ages separate his time from ours, so sweeping has been the changes in our way of life since then. The farmer’s old homestead is still there. Structurally, it has not changed a great deal, but how amazed he would be to see the labour-saving devices and mechanical aids which have replaced the indoor and outdoor staff he used to employ. One tractor now does more work in a day than all his fine horses could achieve in the time. Part of the great stable is a deep litter house for poultry, a couple of stalls only being retained for a hunter and a child’s pony. The old carriage house now garages a modern motor car. Yes, there have been many changes and the contents of the old leather-covered pocketbook indeed appear to be – in the words of Farmer Braddon’s grandson – “ancient history.”

Cecil T. Collacott, 1957.

Visits: 246