George Fox was born in September 1624 to Christopher and Mary (nee Lago) Fox at Drayton-le-Clay, Leicestershire. He was the eldest of four children who’s father, Christopher Fox, a successful weaver, called “Righteous Christer” by his neighbours, and his wife, Mary. Christopher Fox was a churchwarden and was relatively wealthy; when he died in the late 1650s he left his son a substantial legacy. From childhood George was of a serious, religious disposition. There is no record of any formal schooling but he learned to read and write. “When I came to eleven years of age”, he said, “I knew pureness and righteousness; for, while I was a child, I was taught how to walk to be kept pure. The Lord taught me to be faithful, in all things, and to act faithfully two ways; inwardly to God, and outwardly to man.”Known as an honest person, he also proclaimed, “The Lord taught me to be faithful in all things…and to keep to Yea and Nay in all things.” As he grew up, his relatives “thought to have made me a priest” but he was instead apprenticed to a local shoemaker and grazier, George Gee of Mancetter. A constant obsession for Fox was the pursuit of “simplicity” in life, meaning humility and the abandonment of luxury, and the short time he spent as a shepherd was important to the formation of this view.

George Fox knew people who were “professors” (followers of the standard religion), but by the age of 19 he had begun to look down on their behaviour, in particular drinking alcohol. He records that, in prayer one night after leaving two acquaintances at a drinking session, he heard an inner voice saying, “Thou seest how young people go together into vanity, and old people into the earth; thou must forsake all, young and old, keep out of all, and be as a stranger unto all.”

Driven by his “inner voice”, Fox left Drayton-in-the-Clay in September 1643, moving toward London in a state of mental torment and confusion. The English Civil War had begun and troops were stationed in many towns through which he passed. In Barnet, he was torn by depression (perhaps from the temptations of the resort town near London). He alternately shut himself in his room for days at a time or went out alone into the countryside. After almost a year he returned to Drayton, where he engaged Nathaniel Stephens, the clergyman of his hometown, in long discussions on religious matters. Stephens considered Fox a gifted young man but the two disagreed on so many issues that he later called Fox mad and spoke against him. Over the next few years Fox continued to travel around the country as his particular religious beliefs took shape. At times he actively sought the company of clergy but found no comfort from them as they seemed unable to help with the matters troubling him.

In 1647 Fox began to preach publicly: in market-places, fields, appointed meetings of various kinds or even sometimes “steeple-houses” after the service. His powerful preaching began to attract a small following. It is not clear at what point the Society of Friends was formed but there was certainly a group of people who often travelled together. At first, they called themselves “Children of the Light” or “Friends of the Truth”, and later simply “Friends”. Fox seems to have had no desire to found a sect but only to proclaim what he saw as the pure and genuine principles of Christianity in their original simplicity, though he afterward showed great prowess as a religious legislator in the organization he gave to the new society.

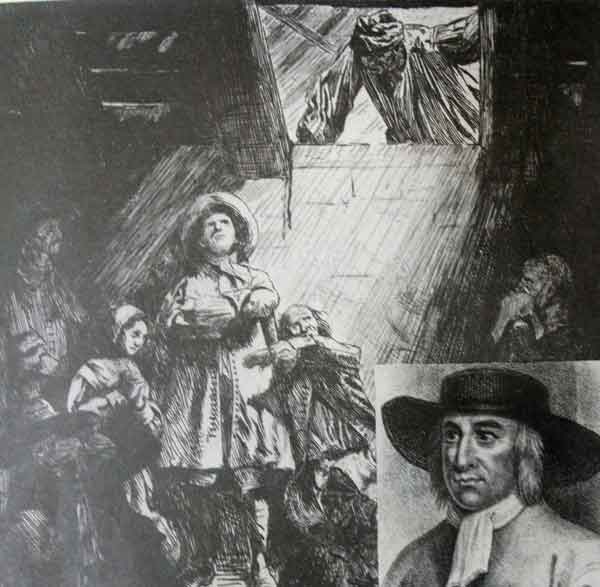

Fox was imprisoned several times, the first at Nottingham in 1649. At Derby in 1650 he was imprisoned for blasphemy; a judge mocked Fox’s exhortation to “tremble at the word of the Lord”, calling him and his followers “Quakers”. Following his refusal to fight against the return of the monarchy (or to take up arms for any reason), his sentence was doubled. In the summer of 1653 he was again arrested at Carlisle for blasphemy.It was even proposed to put him to death but Parliament requested his release rather than have “a young man … die for religion”. Further imprisonment came at London in 1654 and the following year is where his story is taken up with his journey to Cornwall and his subsequent arrest and imprisonment at the infamous ‘Doomsdale’ Gaol (below left) in Launceston Castle.

Fox was arrested at St. Ives with two of his companions, by a Major Ceely, who, as justice of the peace, committed them ‘to the keeper of his higness’s gaol at Launceston, or his lawful deputy in that behalf.’ The first impression of the in habitants of the town evidently did not prepossess Fox, who describes them in his ‘journal’ as ‘dark and hardened.’ For nine weeks the ‘Friends lay in ‘Doomsdale’ awaiting trial, ‘and though many were greatly enraged against them, and expected that these prisoners, who thou’d and thee’d all, and did not put off their hats to any man, should at the assizes be condemned to be hanged if they did not pay that respect to the bench; yet there were many friendly people, out of several parts of the country, that came to visit them; (and) many were convinced of the truth of the doctrine held forth by them. At the time of the assizes, abundance of people came from far and near, to hear the trial of the ‘Quakers;’ who being guarded by the soldiers and the sheriff’s men to the court, had much ado to get through the multitude that filled the streets: besides the doors and windows were filled with people looking out upon them.’

The trial resolved itself into a prolonged wrangle between the Chief Justice of England, Glyn, and the accused. Commanded to take off their hats, the prisoners refused, and Fox pleaded not only the Bible but English law to prove that no necessity existed for them to do so. The judge, exasperated at this cried “Take him away, prevaricator! I’ll ferk him,” and the prisoners were accordingly ‘taken away, and put among the thieves. But presently after the judge called to the gaoler, “Bring them up again,” to which they subsequently were returned to face the judge. “Come,” he said, “where had they hats from Moses to Daniel? Come, answer me; I have you fast now.” Fox replied, “Thou mayest read in the third of Daniel, that the three children were cast into the fiery furnace, by Nebuchadnezzar’s command, with their coats, their hose, and their hats on.” This infuriated Judge Glyn, and having no reply to Fox, he cried again, ‘Take them away, gaoler.’ Accordingly they were taken away to spend the rest of the morning suffering amongst the thieves. In the afternoon they were again brought before the judge and the wrangle was renewed, beginning with the lawfulness of taking an oath, and ending with a demand from Fox, which the judge refused, that their commitment should read. Fox thereupon asked one of his fellow-prisoners to read it, as he had a copy; but the judge refused stating “it shall not be read, gaoler, take him away; I will see whether he or I shall be master.” For a third time Fox was removed, and for the third time he was recalled, when he managed once more to defeat the Chief Justice. Fox insisted to have the mittimus read; and the people being eager to hear it, he bid his fellow-prisoner to read it up, which he did according to the copy already mentioned. Major Ceely, having signally broken down in his attempt to prove the charge of treason he had originally brought against the three Quakers, now accused Fox of having in the Castle Green struck him such a blow as he had never had in his life. Fox demanded corroborative evidence of a charge which evidently astounded him, but this was not forthcoming, Ceely afterwards explaining that the ‘blow’ was simply a rebuff in theological argument; yet the judge once more cried “Take him away, gaoler,” Judge Glyn also fined the three prisoners twenty marks apiece, for not putting of their hats, and to be kept in prison till they paid the fine.

The three refused to pay the gaoler seven shillings a week each for themselves and as much for their horses and as a consequence the gaoler as was put at the time, ‘grew so very wicked, that he turned them onto a nasty stinking place, where they used to put persons condemned for witchcraft and murder.

The place was so noisome that it was observed few that went in did ever come out again in health. There was no house of office in it; and the excrement of the prisoners that from time to time had been put there had not been carried out (as we were told) for many years. So that it was all like mire, and in some places to the tops of the shoes in water and urine; and he would not let us cleanse it, nor suffer us to have beds or straw to lie on.

At night some friendly people of the town brought us a candle and a little straw; and we burned a little of our straw to take away the stink. The thieves lay over our heads, and the head jailer in a room by them, over our heads also. It seems the smoke went up into the room where the jailer lay; which put him into such a rage that he took the pots of excrement from the thieves and poured them through a hole upon our heads in Doomsdale, till we were so bespattered that we could not touch ourselves nor one another. And the stink increased upon us; so that what with stink, and what with smoke, we were almost choked and smothered. We had the stink under our feet before, but now we had it on our heads and backs also; and he having quenched our straw with the filth he poured down, had made a great smother in the place. Moreover, he railed at us most hideously, calling us hatchet-faced dogs, and such strange names as we had never heard of. In this manner we were obliged to stand all night, for we could not sit down, the place was so full of filthy excrement.’

Fox relates how his imprisonment helped spread the light of God into Cornwall. ‘And indeed my imprisonment there was of the Lord, and for His service in those parts; for after the assizes were over, and it was known that we were likely to continue prisoners, several Friends from most parts of the nation came in to the country to visit us. Those parts of the west were very dark countries at that time but the Lord’s light and truth broke forth, shone over all, and many were turned from darkness to light, and from Satan’s power unto God. Many were moved to go to the steeple-houses; and several were sent to prison to us; and a great convincement began in the country. For now we had liberty to come out, and to walk in the Castle-Green; and many came to us on First-days, to whom we declared the Word of life.’

What was the more amazing considering their treatment was that the Colonel Bennett who had purchased the goal and lands belonging to the Castle and had placed the the head gaoler, was a Baptist teacher and a deeply religious man. However, the suffering Quakers petitioned the Quarter Sessions at Bodmin to improve their conditions, and the justices ordered that the door of ‘Doomsdale’ should be opened, and that they should have liberty to cleanse it, and to buy meat in the town. They also sent word to Oliver Cromwell detailing their sufferings who thereupon sent an order to the governor of Pendennis Castle to examine the matter. At about the same time one of Fox’s friends ‘went to Oliver Cromwell, and offered himself body for body, to lie in Doomsdale prison in his stead, if he would take him, and let George Fox go at liberty. But Cromwell said he could not do it, for it was contrary to law; and turning to those of his council, “which of you, would do so much for me if I were in the same condition.”’

Thus, the three Quakers continued in prison, but under less severe restrictions and were allowed the liberty to walk in the Castle Green, where on Sundays they would preach and hold disputations with professors of other forms of Christianity. Fox mentions that he was often in personal danger because of his preaching, and narrates how once a soldier drew his sword upon him, and how at another time his gaoler allowed into his cell a man who purposed to slay him with a knife. With this new found liberty ‘the Friends’ were much alarmed by the light-heartedness of the dwellers in Launceston. They protested, but fruitlessly, against Major–General Desborough (who had been sent down by Cromwell to offer them liberty if they would promise to go home and preach no more) playing bowls in the Castle Green with the justices and others (below left). Fox subsequently drew up an address ‘To the Bowlers in the Green,’ ‘to all you vain and idle–minded people, who are lovers of sports, pleasure, foolish exercises, and recreations, as you call them,’ warning them to consider of their ways and repent. Furthermore, observing ‘how much,’ to use his own words, ‘the people (especially they who are called the gentry) were addicted to pleasures and vain recreations,’ he was moved before he left the place to issue a solemn warning to then not to misspend their time.

The following year ‘the wicked gaoler received some recompense for his past deeds; for he was turned out of his place, and for some criminal act was cast into gaol himself and being so unruly, that he was by the succeeding gaoler placed into ‘Doomsdale’….. And died in prison. Retribution is not, however, recorded for the perjured Ceely nor for the then Mayor of Launceston, who was a fierce persecutor, casting in prison all he could get; and he did not stick to search substantial grave women, for letters, as supposed. Fox, however, took a somewhat ingenious revenge upon him. “A young man having come to see us, who came not through the town,” he says, “I drew up all the gross, inhuman, and unchristian acts of the Mayor, to him I gave it, and bid him seal it up, and go out again the back way; and then come into the town through the gates. He did so; and the watch took him up, and carried him before the mayor, who presently searched his pockets and found the letter, wherein he saw all his actions characterised. This shamed him so, that from that time meddled little with the servants of the Lord.”

After remaining in gaol for six months, the three ‘Friends’ were released on July 13th, 1656. Fox left Launceston, but returned sometime soon after his liberation to visit ‘Friends.’ He twice more came into Cornwall — in 1659 and again in 1663 — but he does not appear to have again set foot in Launceston again.

In the last years of his life, Fox continued to make representations to Parliament about the sufferings of Friends. The new King, James II, pardoned religious dissenters jailed for failure to attend the established church, leading to the release of about 1500 Friends. Though the Quakers lost influence after the Glorious Revolution, which deposed James II, the Act of Toleration 1689 put an end to the uniformity laws under which Quakers had been persecuted, permitting them to assemble freely.

Two days after preaching, as usual, at the Gracechurch Street Meeting House in London, George Fox died between 9 and 10 p.m. on 13 January 1691. He was interred in the Quaker Burying Ground, Bunhill Fields, three days later in the presence of thousands of mourners

Visits: 195