.

Interred at St. Stephen’s after her death at Kensey Cottage, St. Stephen’s on July 27th, 1906, is Harriet Maynard. She was born in Surinam, South America in 1851 to a Surinam slave and a white English father. Surinam (modern Suriname) was former Dutch Guiana, but changed hands with the British administration, ending up with Dutch oversight. Legal tradition throughout the Caribbean decreed that the status of children was dictated by the status of the mother. Thus this legitimated a culture of sexual exploitation of Black women by white men, for slaves were extremely valuable financial assets and more. For they also represented status for the owner. The more slaves, the more status. The slave owner and Harriet’s father was William Maynard a middle-class white Englishman and at the age of five, Harriet moved to England under the care of him. Whilst in Surinam, he attended the Moravian Church, so it is believed that he was of that faith. The Moravian Church is one of the oldest Protestant denominations in the world, with its heritage dating back to the Bohemian Reformation in the 15th century.

However, William would not have been positively received initially, as he had formed a relationship with a Moravian woman of some standing in the Moravian community in Ockbrook, Derbyshire, a 49-year-old spinster, called Rachel Spence, whom despite the revealed scandal, he subsequently married. This was the time that a white man such as William Maynard could not be married legally to a Black woman (regardless of whether she was a slave or not), and so had opted for the local tradition of a ‘Surinam marriage’, in which the mother and another person would escort the girl into the man’s bedroom, and then announce to the immediate locality the nature of the event. From Moravian records, it is known that Harriet’s mother was the personal slave of William Maynard, and was probably his ‘housekeeper’—the standard euphemism for such arrangements of concubinage. So, around 1854, Having almost certainly set both Harriet and her mother free, William brought his ‘daughter’ back to England with him and Harriet became part of the Moravian Sisters’ House, where she would have been looked after and cared for.

At the time of his marriage, William Maynard was about 59 and Rachel Spence 10 years his junior, so the likelihood of the marriage producing any children was very slim. Census records throughout Harriet’s life do suggest that this was a close family, given the close proximity of family members and one into which an illegitimate black girl would be received warmly, which is quite remarkable given the age. The one thing that is known, is that some member of the Spence family, were involved with the world of art, painting specifically and this possibly helped guide Harriet to later train as an artist.

In 1861, Harriet can be found at school at East Tytherton which had its own Moravian community. It is not known how long she stayed there, but her father died just two years later. William and Rachel Maynard were by then living in Adelaide Road, Kentish Town in London. By the 1871 census, Rachel and Harriet are shown as living in Rochester Road, in nearby Camden, with Harriet being listed as a daughter, presumably at home looking after Rachel, who was now 64 years old. More proof that Harriet had been accepted by the Spence family, came in that Rachel’s sister, the unmarried Eliza Spence was also staying with them. Rachel passed away in 1879, aged 72. By 1881, Harriet enrolled as an Art Student and more importantly is seen staying with her ‘aunt’ Ann Spence (née Benham) and her family at No. 6 Grove, St Pancras, which is further proof that she had been widely accepted by the Spence family. Also living here, was Ann’s son, Ernest who is shown as being a scholar here in 1881. Ernest would go on to become an established artist himself, and who was accepted by the Royal Academy at least nine times. We do know, however, that Ernest, and his Medical Student brother, Daniel, are very much part of an artistic family, both of the brothers marrying artists, and (in the 1891 census) living in the Isle of Wight.

Ten years later in the 1901 census, we find Harriet visiting a Hannah E. Short at 40, Lillieshall Road, Clapham, London, with the census describing her as living by her own means (birthplace given as Surinam). What proves a little difficult to find out more on Harriet’s career, is that there were two artist’s named Harriet Maynard, and little is known of her life between 1891 and 1901 but in 1895, a Harriett M. Maynard exhibited ‘A Cornish Fishing Village‘ (SWA), giving her address as 40, Lillieshall Road. Listed in the Falmouth (RCPS) catalogues under H. M. Maynard, she exhibited three titles in 1897: ‘The Watched Pot Never Boils‘, ‘Ready for Church‘ and ‘On the Edge of the Heath‘, and one in 1898, ‘Porthmeor Beach, St Ives‘. In 1902 she is listed under H. Maynard, when she entered just one title, her 1897 picture ‘The Watched Pot Never Boils‘ at a reduced asking price. In November 1898, she supported the Committee of the St Ives Arts Club by signing a letter about the artists’ concerns around proposed building development in St Ives. cornwallartists.org

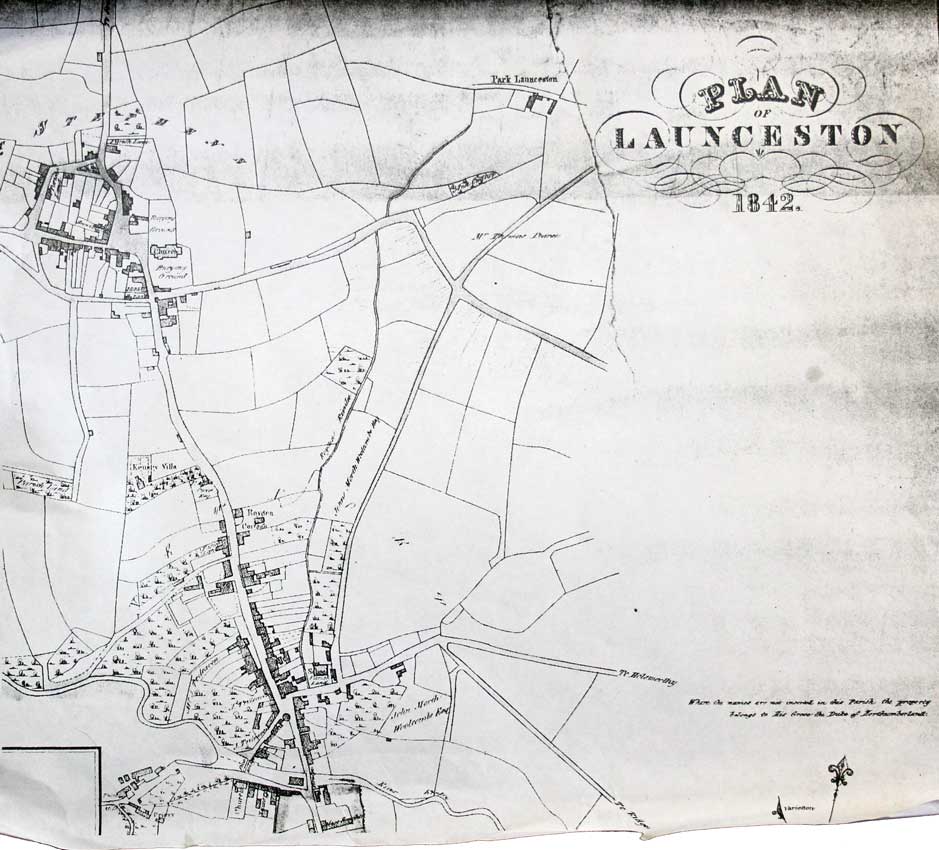

Soon after 1901, Harriet was the guest of the Reverend Charles Baskerville Langdon, a Roman Catholic priest who ran a bordering school and who had set up a mission at Launceston in 1886 at Kensey Villa (the present presbytery), St. Stephen’s Hill, Launceston. It is here that Harriet spent the rest of her life, possibly having converted to Catholicism, living in Kensey Cottage. She passed away on July 27th, 1906 at Kensey. In her will, dated August 17th, 1906, she left a total of £3,479 13s. 1d. which in today’s money is close to £250,000!

Much of the background information has been taken from the excellent piece from the Wiltshire OPC Project by Nigel Pocock.

Visits: 68