.

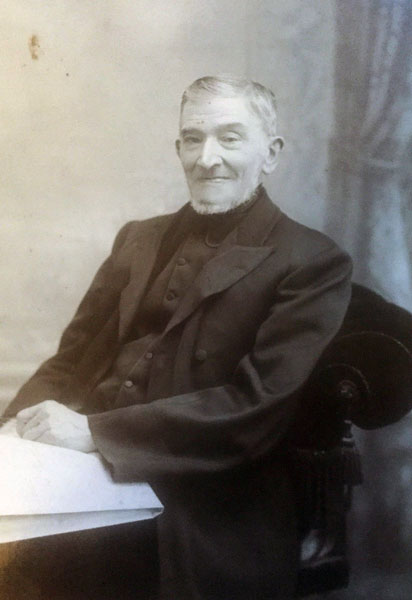

Richard was born on the 3rd of August 1817 at St. Thomas, Launceston to Mr and Mrs John Robbins. Richards education was at the National school in Launceston. On leaving school he left Launceston to gain business experience at Teignmouth and Dartmouth but in 1840 he married Mary Farthing and he returned to Launceston to set up business as a Shoemaker at Broad street, Launceston trading as Robbins Shoemaker which was carried out beneath the sign of ‘The Golden Boot’, which has been kept in a state of fine preservation and remained on the same building since 1840 until it was rescued and placed for safekeeping in Lawrence House Museum.

Together the and Mary had six children George Farthing Robbins 1841-1885, Caroline Robbins 1845, Sir Edmund Robbins 1847-1922, Fanny Robbins 1850, John Robbins 1853 and Sir Alfred F. Robbins 1856-1931. Richard was very keen on his history of the town and gave lectures in various places regarding this subject.

His wife Mary died on the 24th of November 1881 at Launceston.

Richard was a valued member of the borough town council being elected in 1877 and along with Richard Peter was one of the enlightened members who helped fight the demolition of the Southgate. In his lecture of 1884, he stated; “ Take, for instance, the demolition of Westgate and the destruction of Northgate, through the last-named of which I have passed thousands of times. What on earth could have induced the Corporation to destroy the Northgate when the traffic had been diverted from that part of the town I am at a loss to conjecture. Happily, the institution of which they were members ceased to exist the year after.

When we consider that, had their political decease taken place a year earlier, we should still have the Northgate with us, we cannot do otherwise than lament their longevity as a public calamity.”

Richard remained on the town council for ten years and was also a member of the local board of Health. He was a regular worshipper at the Congregational church, in whose welfare he took a keen interest and was a consistent contributor to its funds. He also took a prominent part in the formation of the Launceston volunteer fire brigade and was its first officer.

It was a fact that he was known to be quite a radical for the time and was a strong supporter of the Liberal party and through him, Richard Peter and Edward Pethybridge, the old Conservative guard that had held power for several years were swept away and Launceston was brought into a new age of enlightenment.

He was a great letter writer. Below is one such letter that was published and later used by the Liberal party for election purposes..

The Hungry Forties

Because of the way in which it kept up the price of bread. Parliament had just forbidden the importation of all foreign wheat when the price was below 80/- a quarter; and the labourers in my part of the country could scarcely have a wheaten loaf from one year’s end to the other, having to put up with barley bread. “ My home was the ancient borough of Launceston, in Cornwall, which at that time was an Assize town as well as a marketing centre for a large agricultural district, and the home of an old-established woollen industry. It was, therefore, a favourable specimen of a country place, and yet when William Cobbett visited it at the time I was four years old— and my recollections begin in that year, 1821, when George IV. was crowned, for I was present at the local rejoicings—he was told by a tradesman (and the statement is to be found in his “Rural Rides”) that the people in general there could not even afford to have a fire in ordinary, and that he himself had paid threepence for boiling a leg of mutton at another man’s fire ! “But if food and fuel were dear for a trades- man, how much dearer did they seem to the labourer and the artizan ! We are being told that if Protection is brought back to us wages will rise and the working man be better off. What was the case in my young days ? I will tell the working men of to-day, and let them judge for themselves, pledging myself not to make a single statement I cannot vouch for as having seen for myself the facts. “ The wages of shoemakers at the time of which I am speaking were from 9/6 to 10/6 a week ; and their hours of work were from six o’clock in the morning to eight at night from Lady Day to the first Monday after the 8th of September, and from eight in the morning to eight at night the rest of the year, with half an hour allowed for breakfast in the summer, an hour for dinner, and half an hour for tea—about twelve hours’ daily work for an average of 10/- a week, and bread at the price it then was. They were given one whole holiday in the year, and that was Christmas Day, for they had to work all Good Friday ; but they had half a day off on Easter Monday, Whit Monday and Tuesday, and Mayor-choos-ing day, and the evening off on St. Crispin’s Day. I myself knew a good workman at the leading boot-shop in the town whose average wage was never over 9/- weekly throughout his life, not even when bread was 2/- the quartern loaf.“ Carpenters and masons were paid a little better, their wages ranging from 11/- to 12/- a week, and their hours of work being from six in the morning to six in the evening for eight months in the year, and from seven to five the other four months. The wages of tailors were from 10/- to 12/-; and they worked from six a.m. to eight p.m., except in November, December, January, and February, when the hours were from eight to eight; and they were allowed an hour for dinner, but if they wanted tea it had to be brought to them as they sat on their shop boards. Woolstaplers and fell-mongers worked from six to six for from 9/- to 10/6 per week, while day labourers were paid from 7/6 to 8/6 in the town, and 7/- to 8/- in the country, the wages coming partly in the latter case out of the poor rate ! The custom when I was a boy was for able-bodied men to attend a vestry or parish meeting, and their services to be put up to the biggest bidder among the farmers present. Sometimes the price bid was no more than iod. a day, andthis would be made up to 1/2 or 1/3 by the parish. What was the result ? The men, who would have been free and independent under a better system, were compelled to be paupers. “ I do not say that there were no working men who were better paid than those I have mentioned. The curriers and hatters, for instance, were the aristocrats among the artisans of the town ; but they were the exceptions, and, though they earned good money, the ropers and the woolstaplers and the basket makers had no more than from 8/- to 9/- a week. ”

In 1884 he gave a lecture on the previous 60 years history of Launceston in aid of Launceston’s Fire Brigade. Due to his experience with various machines in the boot and shoe trade, Richard was called upon to repair the ancient fire engines of the town on several occasions.

It was in 1883 that he made the decision to take his son-in-law, Edward Bloxsome into a partnership, a decision that was to have such fateful consequences for the business. Edward a travelling draper, had married Richard’s daughter Fanny in 1878, had initially invested £400 into the business, but he soon withdrew £350 in cheques. He also had some considerable personal debt and soon drew another £250 from the business, a not too considerable figure at the time. The accumulative result was that the business soon ran into cash flow problems by October 1885 and although Richard tried to settle with the creditors, Edward Bloxsome insisted that his personal debts should be including which Richard refused. With an impasse, Richard was left with no other option but to file a petition for bankruptcy to dissolve the partnership.

Once the bankruptcy procedure had been passed Richard moved to London to be nearer his sons. Edward Bloxsome and Fanny’s marriage didn’t survive and he moved away returning to his previous profession. He later remarried and died in 1915 whilst living on the Isle of Wight. Richard meanwhile was given a grand farewell with the town raising a testimonial fund which was presented to him on Monday, September 27th 1886.

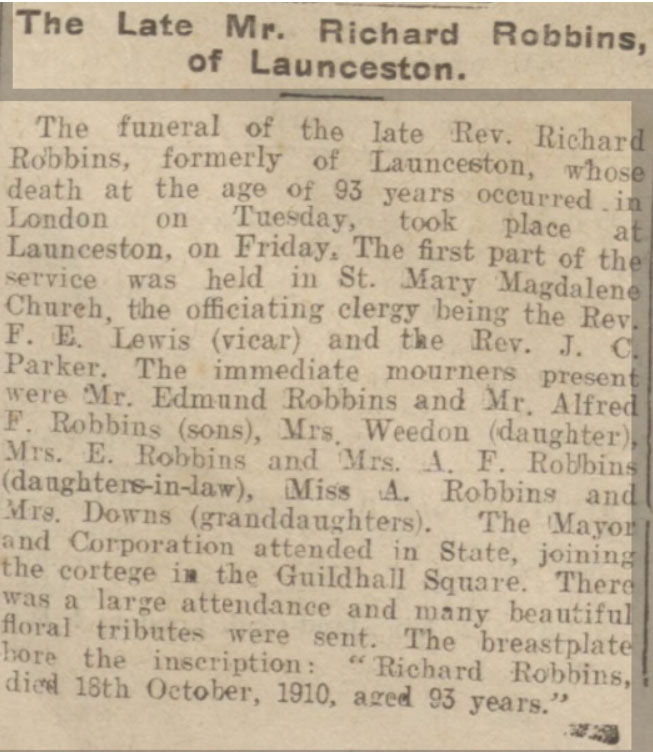

Richard spent the next 24 years living in London with his son Alfred passing the time away writing letters. He eventually passed away on the 18th of October 1910 at London at the age of 93 years having lived through six monarchs. His funeral service was held at St. Mary Magdalene being conducted by the Rev. F. E. Lewis (Vicar) and the Rev. J C Parker (Curate) and he was interred at Launceston.

Visits: 138