.

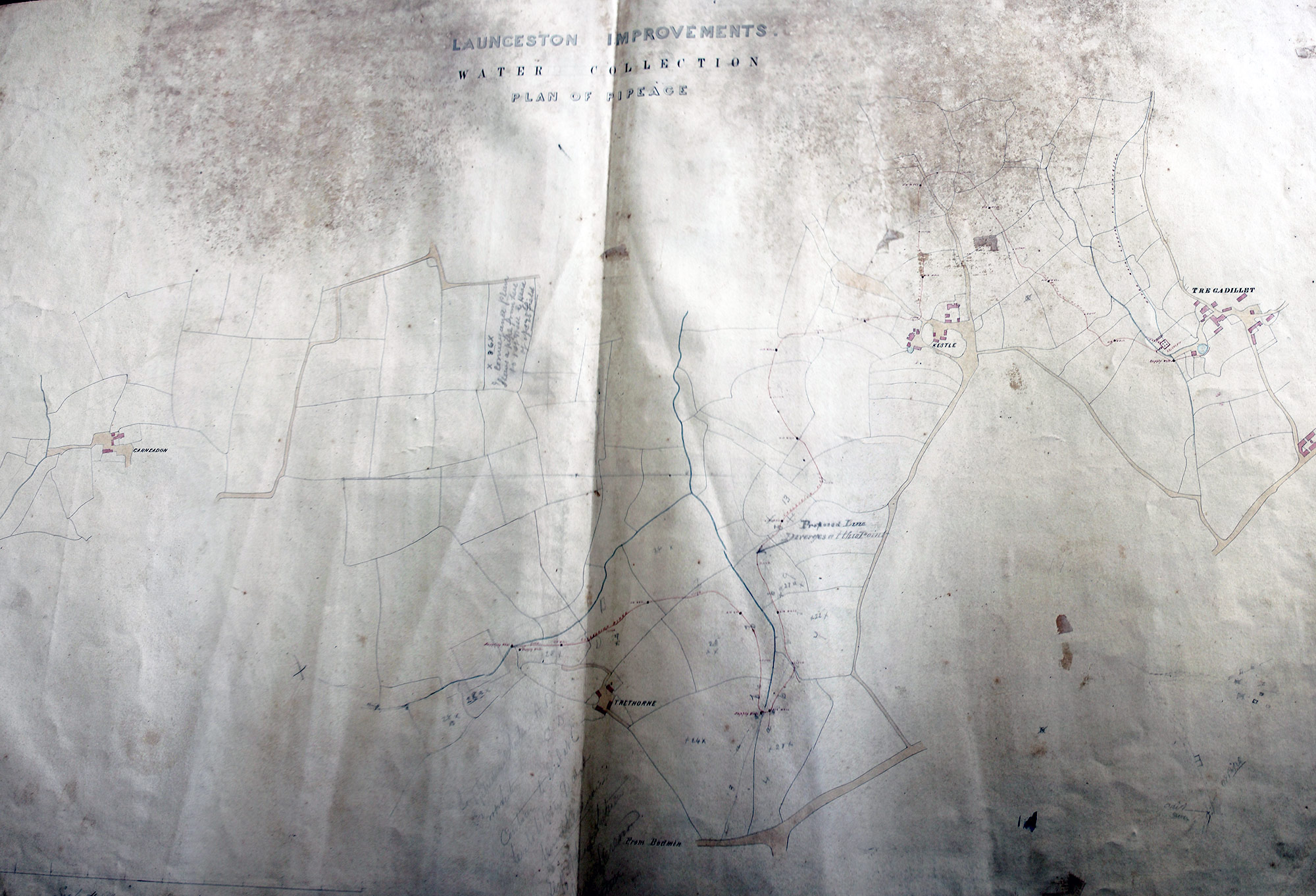

The following is a transcription of Stuart Peter’s research into Launceston’s water supply:

The building of the Windmill reservoir started in 1894 and it was opened during the mayoralty of Mr. John Kittow. It was financed by loan and by coincidence his son, Mr. Horace Kittow, was mayor of Launceston when that loan was finally paid off in the 1920’s.

The Windmill gravity scheme, fed by by pipeline from Bray Down near Altarnun, was not Launceston’s first water supply, of course: earlier in the Nineteenth Century there was a reservoir at what is now the junction of Dunheved road and

Windmill Hill (outside the College), from which pipes ran into the town. The site of that reservoir was Lanivet Green, a name now vanished from memory, and in view of the name of the parish near Bodmin, one wonders from what ancient Cornish word-root this derived. This Lanivet Green source supplied taps at Westgate, Southgate and near the old Jubilee Inn at the top of Northgate street (demolished in 1964), and the scheme was largely financed by a gift of money from the Duke of Northumberland, who then had a country seat at Werrington Park and who was a considerable benefactor in the town in the early years of the century – in return, it might be added, for the considerable political patronage which control of the four Parliamentary seats afforded him (in those days Launceston returned two M.P.s and there were also two elected by the neighbouring Borough of Newport).

BEACON HILL

Also preceding the Windmill reservoir was the Trethorne source ( above, later adapted to assist the supply in the South Petherwin district, and there was a reservoir at Trebursye, which supplied the lower reaches of Launceston and subsequently was used for the Diamond Jubilee swimming baths in Underlane). This supply proved inadequate, however, and was replaced by the Windmill project, as a by-product of which the Windmill pleasure grounds were laid out. Taking its name from the fact that many years ago there must have been a windmill upon it (no evidence exists to prove this though), it was also once known as Beacon Hill, on of the chain of heights on which beacon-fires were lit to convey messages of great tidings the length and breadth of the county.

In addition to the piped supplies, Launceston of course had much earlier supplies of water from wells and streams. One was Harper’s lake, the stream now running along the valley from Chapple through Willow Gardens (the steep slope that abounds St. Thomas road which at the time of Stuart’s piece was still in use as allotment gardens). There is a thought that this stream was at one time diverted to run on a higher course along Western road and thence around the base of the Castle to provide a water supply for the Northgate area. Originally, the supply for the medieval town was by wells and water-carriers, one of whom was chosen by the Prior at the Priory (in Newport) and who “should sleep in a certain chamber of the convent church and, if necessary, rouse the curate.” This water carrier was paid 20s. A year for his wages, and also had to take care of the clock for the year.

A record of 1512 shows that Nicholas Adam entered into a contract with the Mayor and aldermen of that time to make conduits for water, to find lead and solder, and to cast, lay and sand the pipes. Later, reference is made to a little “perle of water which serveth the high parts of Launceston.”

PERSONAL MEMORIES

Fascinating information about Launceston’s water supply before the Lanivet Green scheme in 1825 comes from an unpublished manuscript written by Richard Robbins, one-time proprietor of “The Golden Boot” in Broad street and father of Sir Alfred and Sir Edmund Robbins. Looking back over his long life, he committed to paper his memories of the better part of a century and thus provided invaluable material for the historians. He recounts that in those days:

“ The town was supplied by pumps and conduits, one on the top of Race Hill, Shepherd’s Well, Madford Well Westgate, Westgate street, Bounsalls lane, and Broad street. There were three conduits, viz., Race Hill, which was supplied by a small reservoir, under Madford by the side of the hill, one at the London Inn and at the Jubilee in Fore street (Northgate street); the two latter were supplied from an adit in Bounsalls lane.

“In the summer there was but little water to be had: the pumps and conduits, after 6 p.m. Would be all padlocked until the following morning at 6 a.m.. Pitchers would be placed at the pumps and conduits as early as 3 a.m. And when unlocked there would be a general scrimmage as to whose turn first, often ending with a fight among the women. “In the summer, water was fetched from Northgate Quarry Well, the river and from the Shute at Newport (the latter was the favourite place for the publicans to brew with). Quarry Well was owned by Charles Ruse, who lived in Quarry lane, and who demanded from each of the inhabitants of the hamlet of St. Thomas street, the area between Newport Borough and Launceston Borough) one penny for each household, which was readily forthcoming. “When the Lanivet Green water works were completed in 1825, in the summer the supply was very little better, for the old sources were or had been neglected. The constant supply of water from a shute at Northgate, from Chapple (see reference to Harper’s lake above) was neglected and some time afterwards diverted into another channel.”

THE FLOGGING PUMP

Richard Robbins added that the pump in Broad street was known as “the Flogging Pump,” doubtless due to the fact that miscreants were publicly punished there at one time. There was also a pump on the Walk. He wrote that there were two other conduits, one near the London Inn and the other in Fore street (Northgate street), near the Jubilee Inn, both with slate tanks. In addition to the reservoir in Race hill, there was also one in Broad street (under the square, which still exists today, seen below) which was supplied from the adit in Bounsalls lane.

Richard Robbins also makes further reference to the “good stream of water” from Chapple to the Northgate, which ran in earthenware pipes (“through Miss Pearce’s garden” presumably in Castle street) and then through a shute into a large granite trough near the old Northgate. But, he added, the principle supply for this area was from Quarry Well, mentioned above, which Charles Ruse cleaned out every year and which he kept locked and superintended. His charge for its use by the householders around was met by an annual subscription.

St. Thomas apparently derived no benefit from the Lanivet scheme, but it did provide five public taps in the town. One was at Southgate, where still to be seen carved in granite are the initials of the mayor at the time and the date. Another was in Castle Dyke, near Western road; one “at the old butcher’s shambles facing the church;” another at the bottom of Fore street (Northgate street), by the Congregational Chapel. In the summer though, these taps went dry, and the mayor had to revert to the old custom of padlocking them every night. Women would come as early as 3 a.m. In their nightdresses, to leave their pitchers, and when the town sergeants arrived at 6 a.m. To take the padlock off, there would always be a queue of women and girls. Wrote Richard Robbins; “The cry would be ‘whose turn first?’ And seldom did they part in peace but what there was a squabble with broken pitchers and a trial of strength as to who had the strongest hair.” And he adds drily, “It was a very old saying that when everyone had to take their baking to the common oven and fetch their water in pitchers, that the conduits and bakehouse’s were the two schools for gossip and scandal.”

Visits: 150