.

Much of what follows is from a piece in the Cornish and Devon Post in 1968 written by Robert J. King.

How many of us, as we go about our daily business in that shadow with our eye recording but not remarking the gaunt outline of that “giant stone wedding-cake” as Charles Causley once described it, stop to think of its origins and the wealth of history, of happiness and heartbreak, its walls have witnessed?

In the year following his successful conquest of England in 1066, William Duke of Normandy returned to his native land for a short while, Bishop Odo of Bayeaux and William fitz Osbern being appointed as regents to preside over the uneasy peace which he left behind. The harsh ways in which the Normans treated the newly subjected Anglo Saxon population were starting to sow the seeds of discontent. Throughout the land the conquerors built many castles which symbolised their dominance, and which they often constructed using forced labour. Ill feeling spread among the Saxons, and signs of revolt began to appear in many places. On December 7th 1067, William returned to Britain to find that the first indications of rebellion were starting to manifest themselves. The immediate problem which he faced, though it was to be no means the most important, lay in the South-West, where the City of Exeter had rebelled against the new rulers. Mustering an army, William headed westwards. In the country there was little trouble, but Exeter itself resisted siege for eighteen days, before agreeing to a conditional surrender. A castle was built there before William pursued his successful expedition on into Cornwall.

Once acquired, Cornwall and West Devon were given to Brient de Bretangne, a Count of Brittany, who is believed to have been the first Earl of Cornwall. He held the position until about 1075 or 1076, when he was probably dispossessed after the rebellion of Ralph de Gael. His place was taken by Robert of Mortain, a much more significant figure, who was to have considerable influence on the history of the County.

ROBERT OF MORTAIN’S CASTLE AT DUNHEVED

Robert, Count of Mortain, was a half-brother to William, and was one of the Conqueror’s closest supporters in the invasion of England. His services were rewarded with the Earldom of Cornwall, and it is most probable that he was installed there by 1076. Robert was to become one of the most powerful of contemporary lords. His estates extended into 20 counties, though his greatest strength lay in Cornwall, where either by direct or some 247 manors, a number vastly in excess of that held by the King himself. As a ruler, Robert’s ruthlessness was typical of that of his countrymen. Many of his estates were obtained by simply dispossessing their weaker owners, and it was not surprising that he came to be noted “more for his might than his beneficence.”

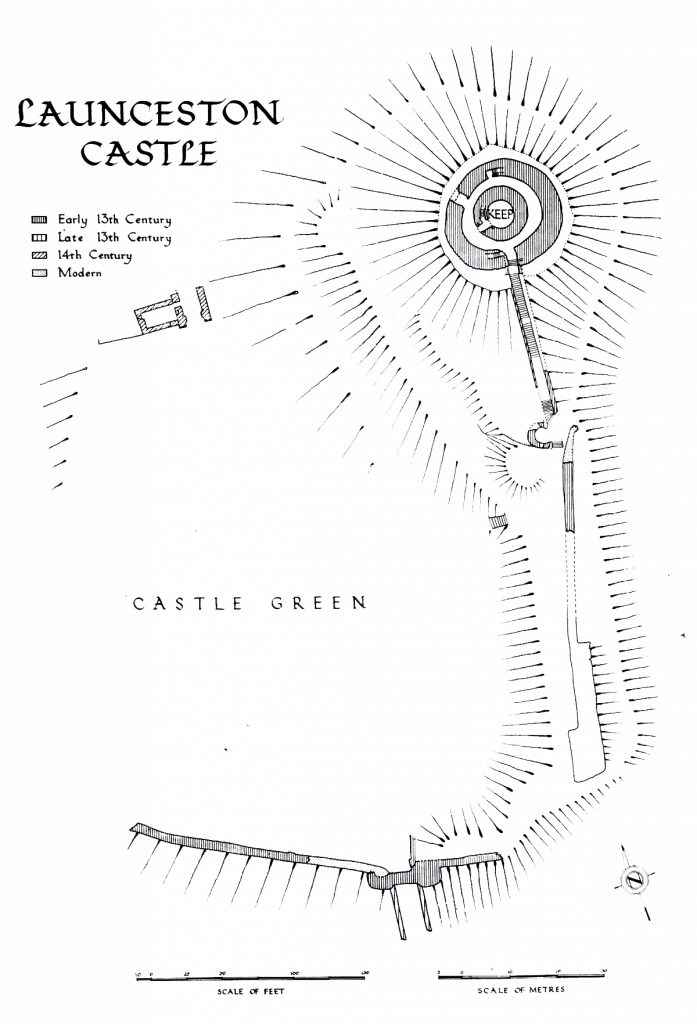

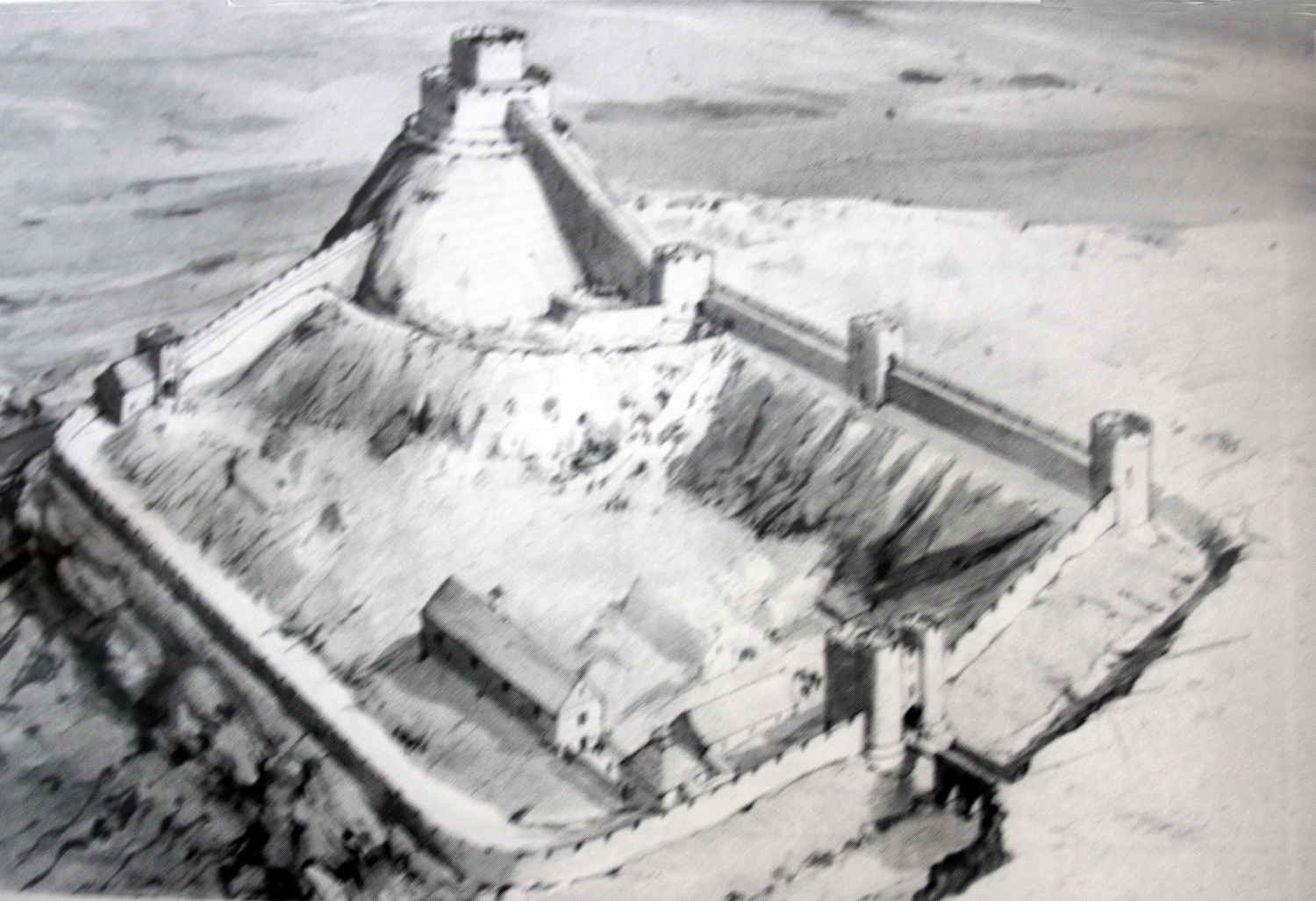

He chose to establish his court and the administrative centre of his domain at Launceston or Dunheved, where a thriving settlement already existed. His decision was to have a great influence upon the later history of the town. From this time onwards it became the centre of Cornish government; the county assizes were held there, and the county gaol situated there, an arrangement which was to continue on into the 19th Century, when the role of assize town was transferred to Bodmin. Within the town, Robert built a castle for his home and the centre of his administrations. Domesday records: “The Earl himself holds Dunheved……The castle of the Earl is there.” The site of Robert’s castle was obtained from the Bishop of Exeter in exchange for Halveth and Botinine, two manors in Devon. As a strategic position its potential was enormous. It was easily defensible. In its compass it included a natural hill dominating a largely flat area, which was itself defended by a precipitous slope to the west. The site was in a sufficiently elevated position not only to overlook the approaches to the Tamar, but to command a view stretching from Bodmin Moor to Dartmoor. The Domesday Survey of 1086 makes the first reference to the castle, but the lack of documentary evidence relating to its early history leaves much in obscurity. Exactly when it was built and what precise form it took are unknown, but from what remains today it resembles a pattern adopted by the Normans, known as motte and bailey. There was a keep or tower on the motte, which was reached by steps scaling the steep slope. At the bottom of the steps was a causeway, the connecting link between the motte and bailey, otherwise divided by a deep moat. Excavations on the site revealed that the bailey rampart was formed by three successive increases in the height of the bank with earth and stones, and the addition of timber ramparts. This seems to indicate that the castle developed along fairly typical Norman lines, of being firstly a timber and earthwork structure, the timber of which was at a latter date replaced by stone.

An alternative theory, however, suggests that it was stone from the first and not timber, though the only evidence provided to justify this is the local scarcity of timber opposed to the relative abundance of good building stone. In fact, most Norman castles developed as timber and earthwork structures at first. This pattern is not however without exception; a very small number were stone from the first, the Tower of London being one instance of this. Such a variance from the standard though came only in response to some basic irregularity in conditions or the need to meet some particular requirement. At Launceston, one can see little justification for this unusual approach.

On the death of Robert in 1090, his son William became Earl in his place. In 1106, William revolted against the reigning monarch, Henry I, and was subsequently imprisoned, his properties becoming forfeit to the Crown.

THE STONE CASTLE

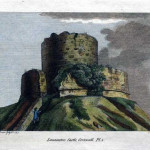

The next Earl of any significance was Reginald de Dunstanville, one of Henry I’s fourteen illegitimate children. He held the title from 1141 until his death in 1175. The age of the stonework of Launceston Castle has become shrouded by time, with no documents to testify to its origins, but the first masonry constructions are generally attributed to Reginald, the work believed to have been executed soon after the middle of the 12th century. This consisted of the erection of the shell keep upon the motte, the stairway linking it to the bailey, and the enclosure of the bailey by a curtain wall. The shell keep upon the motte was a massive structure, its walls being some twelve feet thick. From its battered plinth beneath a string course with a bold torus moulding, it rose up to a wall walk at the top about twenty feet above its floor level. It was not quite circular in plan, but was nearer to an oval with axes of 50 feet 4 inches, and 50 feet. Lean-to buildings were grouped against the wall within the contained space, leaving a clear area in the centre. This arrangement would appear similar to that of Restormel Castle at Lostwithiel, though in this case, the diameter of the shell is about twice that of Launceston. In thickness of the wall are two mural stairways leading up from the ground level to the wall walk. One is reached to the south, opening from the flanking wall of the gateway forming the entrance to the keep, whilst the other opens from an alcove in the north side of the shell. Visible above the alcove are remains of a large rectangular machicolation defending the entrance to the stairway from the wall walk overhead. The complete absence of all masonry above the entrance to the south stairway leaves no clues as to whether or not a similar arrangement existed there, though this is a very real possibility. Such a defensive feature at this point would also have fulfilled the important task of commanding the entrance portal to the shell. In the thickness of the shell to the west is a small chamber about eight feet square, the only opening to it other than the door being a small duct eight inches square, which rises almost vertically from one corner to open at the wall walk. Whatever other functions this performed, it must certainly have acted as a drain in wet weather.

Access to the keep from the bailey was obtained by a staircase running up the south side of the motte. Excavations on this part of the site revealed the foundations of a 13th Century stairway which was 4 feet, 9 inches wide, though a later one was some 7 feet wide. The stairway included in its length two or three narrow landings, and was flanked by walls 3 feet 6 inches in thickness, pierced with arrow loops. The whole was roofed over and covered with lead. At the top, the passage communicated with the keep by a gateway and a port cullis. Part of the groove in which this ran is still visible on the east side of the opening in a piece of dressed stonework which also included a fragment of the jamb with the springers of the gate arch. The gateway itself has now vanished, along with the room above it from which the port cullis was operated. Whilst no evidence is available, it has been suggested that this room was made of timber. In the same way that the gateway is now gone, so also is the passageway, and all that remains to show where it linked up with the shell are some holes where its masonry bonded in with that of the keep wall.

THE BAILEY

At the base of the motte, the bailey spread out to the south and west. At about the same time that the keep was being built, the bailey was enclosed by a curtain wall, of which some portions, principally to the east and south, are still standing. On both of these sides it was defended by a deep moat, whilst to the west an extremely steep natural slope eliminated the need for similar excavations. The moat outside the curtain to the east is now gone. It was filled in and built over much later as the town grew up to the castle.

A small postern opened in the curtain wall a short distance south of its junction with the guard tower at the base of the motte. This postern, which is now destroyed, served as a means of access to the bailey for the inhabitants of the town in the event of a sudden attack. Access to it was by means of a sliding drawbridge crossing the moat. A little further south in the curtain wall was a square tower. Beyond this at the south-east corner of the bailey, where the line of the curtain

changed direction to the west, a round tower was situated. Known as the Witches Tower (left), it fell in 1834, during the construction of Western road, which running beside the south wall of the bailey, came very close to the base of the tower. At the same item, this road destroyed the moat along this side of the bailey. In a curtain wall to the south lay the south gateway, the principal means of access from the town. It was built about 1160 at the same time as the curtain, and it closely resembles the work on the keep. With its battered plinth, and string course of Polyphant stone, the gateway consists of two large drum towers, solid up to their present height. They flanked a central passage which was guarded by a port cullis, and entered by a pointed opening to the south. Part of the groove in which the port cullis ran can be seen on the east side of the passage. There were apparently no other doorways. The typical contemporary port cullis was of oak, shod with iron, and moved up and down in stone grooves by chains and pulleys or sometimes a winding drum. In this case the port cullis was operated from a room above the gate with a window opening to the south. All the masonry of the inside of this gateway has vanished. There was probably a warden’s lodge flanking the opening.

West of the south gateway the curtain wall continued, changing direction in a gentle curve to run northwards. This section of it no longer stands. In the north wall of the bailey lies the second major entrance to the enclosure, the north gate, which is of later construction than the curtain wall. Beyond the north gate to the east, the line traced by the curtain is not certain. It probably ran up to the base of the mound, which it then followed northwards. This is in fact the arrangement illustrated in Norden’s survey. It is also believed that a second wall followed the base of the motte to the south, thus rendering it completely separate from the bailey.

Access to the south gateway was by means of a bridge across the moat. The original bridge had decayed sufficiently to need rebuilding in the later 14th century, and its masonry, instead of bonding in in with that of the gateway, simply butts up against it. The carriageway was 12 feet wide, and flanked by two tall walls which projected forward of the gateway forming a barbican. Offsets in these walls supported the timber floor of the bridge. It was carried across the moat on low arches, and with the barbican was originally about 120 feet long. These features were also largely destroyed by the construction of Western road. The barbican formerly included five arrow loops on each side, but in the sections left standing, only two of these can still be seen. Of the bridge, all that remains is a small section including two blocked arches of those which once carried it over the moat.

THE TOWER

It is not until the 13th century, and the time of Earl Richard of Cornwall, that any more major constructions emerge. Richard, who was the younger brother of the reigning monarch Henry III, held office from 1227-72. In addition to some slightly lesser works, it is most probable that his lifetime saw the erection of the other two major structures upon the motte: a high tower within the original keep, and a low mantelet wall outside it.

Excavations carried out in 1968 revealed that a certain amount of energy was devoted to improving the ailing defences of the motte, which by this time were beginning to need attention, the lower end of the staircase giving access to the keep terminated slightly above the general level of the bailey on a terrace, where a guard tower was now built. There was also a wall on the terrace, for which further support came to be provided by the addition of a retaining wall. It has also been shown that the original ditch dividing the motte and bailey had begun to fill up, and at this time a second moat was dug. It passed in front of the guard tower, to which access was gained by means of a drawbridge.

The terrace and well can still be seen, but all that remains of the guard tower is one single “D” shaped flank. On the ground floor are the battered remnants of a single round headed window, which has long since been deprived of its dressed stonework, whilst inside there is evidence of a small staircase which led up to a first floor over the gate arch. This would then very probably have linked up with the wall walk of the north end of the bailey curtain, which in Norden’s illustration of 1584 is seen to join the guard tower at this point.

The new tower which came to be constructed within the original keep had walls which were 10 feet thick, and which rose to their summit some 30 feet above the wall walk of the shell. It was almost circular in plan, and separating it from the earlier keep was a space varying in width from 6 feet to 10 feet 6 inches. This space was then roofed over at the level of the top of the shell, thus extending the wall walk and widening the fighting platform. Though this has now disappeared, the holes which contained the timbers supporting it can still be seen in a circle around the wall of the tower. The tower contained two rooms, one above the other and 18 feet 6 inches in diameter. The lower room, which may have been either a store or a dungeon, has one opening, a doorway, to the west can still be seen with all its dressed stonework completely intact. From within the door opening, a mural stairway gives access to the upper chamber, before continuing up to the summit. This chamber constituted some sort of living room. Its floor, no longer remaining, rested upon timber joists spanning the width of the tower, and in the north side of its wall are the remnants of an old fire place. The low mantelet wall, of contemporary construction, was a relatively small structure, being about 3 feet thick and 6 feet high.

The motte at its summit therefore now bore three concentric lines of defence, which must have presented a very formidable sight, due tribute to which was paid by Leland, who, on his visit to the castle in 1540, wrote: “…and the moles that keep stondith on ys large and of a terrible highth, and the arx of it, having three several wardes, is strongest, but not the biggest that I ever saw in any ancient work in England.” The north gate to the bailey suggests by its mouldings that it was built probably in the mid to later 13th Century, and inserted into a curtain wall. It is in a much better state of repair than the south gate, though its outer arch was restored in the 1960’s. It is rectangular in plan, and has a pointed ribbed vault over the passage. The inner arch , which is original, features two square buttresses flanking its pointed opening. It was defended by two port cullises, one at each end. To the west of the gateway, and opening from it, is a small chamber known as Doomsdale. Its sparse interior reveals a small cupboard at the east end in the wall, two small square headed windows, and the remains of a third. Two of them are blocked up, the one in the west wall alone remaining open.

In 1337, Cornwall, previously an Earldom, became a Duchy, and Edward III, then King of England, became the first Duke. His surveyors investigating the castle found many defects. “There is a castle whose walls are ruinous. And they ought to be maintained by those holding knights fees belonging to the honour of the same castle. And there are in the same castle a certain hall with two cellars which needs re-roofing, a sufficient kitchen attached to the same hall, a small upstairs hall called the Earl’s chamber, with a chamber and a little chapel, whose walls are of timber and plaster, and the timber therof almost disjointed. And two chambers above the two gates, covered with lead, one old and decayed little hall for the constable with a chamber and a cellar and a small kitchen attached. There is also a chapel in good order apart from the windows, which are decayed, two stables for ten horses in good order, a gaol badly and inadequately covered with lead and another prison called ‘the larder’ weak and almost useless. And one passage leading up from the castle to the high tower newly covered with lead, but the steps of which are defective. And there are in the same tower two chambers whose doors and windows are of no value. And the aforesaid tower has two mantelet walls of stone, of which one portion containing by estimation three perches has fallen to the ground……”

FEUDAL TENURE

This survey presents the first documentary evidence of what buildings existed in the bailey. The reference to the fact that repairs should have been carried out by the “holders of knights’ fees” points towards the conditions of feudal tenure from the castle, and the fact that these conditions could not have been very strictly adhered to in the preceding years. It appears that there were three halls, a chapel, the gaols and the stables. The first hall was probably the main hall, and the one later referred to by Leland as being for “syses and sessions,” whilst the third one was the Constable’s dwelling. It is significant to notice that the Earl’s hall was in a bad state of decay. This is probably the result of a tendency among later Earls to be absent from Launceston over long periods, the hall consequently deteriorating through neglect. Some of the Earls were reigning monarchs, while others had more distant interests. Richard of Cornwall for example became King of the Romans in 1257, and much of the remainder of his life was spent abroad seeking acclaim for his disputed heritage.

Following the survey, which records the bad conditions into which the castle had lapsed, repairs were put in hand to arrest the decay. By 1345, most of the work which the survey had indicated a need for had been carried out. The main hall was re-roofed with slate, and repairs were made to the curtain wall and the mantelet wall, the cost for the two amounting to some £40. The accounts for the work survive in the Black Prince’s Register, and throughout his period of office, necessary maintenance work was carried out. The bridge to the south gate of the bailey was rebuilt in 1382/3 for a cost of £70 8s. 8d.

More restoration work was carried out in the years 1406/09. Accounts for this work survive and contain many references to the materials and methods used and the labour involved. Their value lies in the fact that no records of this type from an earlier date survive in existence, and there is a possibility that the material employed and their sources of supply many be the same as those in the original building. Landron, possibly modern day Landrends, or Landrean, is listed as being the source of supply of the rough stones used in the walls. For quoins and jambs, the dressed stone came from Polyphant, while the lime used in the mortar came from Halton on the Tamar. Treculdru Bridge, which cannot be definitely traced, but which probably lay on the Tamar, was the source of most of the sand, though six mysterious loads were for some reason brought from the sea. Although sand from the sea, owing to its high salt content, is not completely satisfactory for building, its use was not altogether unknown. Records indicate that it was used on a fairly large scale in 1266 in the construction of Dover Castle, and in considerable quantities on Pevensey Castle.

The work necessitated the employment of masons, tilers, plumbers, carpenters, quarrymen and labourers, the numbers being determined by the current volume of work and the time of year. As many as eighteen men were employed at any one time, whilst in mid winter there was only one mason, for whom it is recorded, a purchase pf 3 lbs. of candles was made whilst he worked at night in the winter months. The wages earned by the men varied. The masons got 4d. Per day with the exception of one who got 5d., this in fact being the greatest amount paid.

FIGHTING THE IVY

Sundry purchases made in connection with these repairs include timber and stone, and “lathnails,” “leadnails” and “boardnails.” The most significant piece of information concerning how the tops of the walls were finished lies in the record the purchase of 78 feet of cresting, though it is not known upon which wall this was used. Other entries record the purchase of glazing bars and staples in 1409 for use on the “rekil,”possibly corner windows of the chamber, and a new key to the room over the south gate, though it was in this and other instances referred to as the east gate. The next year some metal hooks were bought to pull down the ivy growing on the castle walls.

More work was carried out in 1460-64. In 1460 a payment was made for “shaping and making the timber for le medell fiore of the tower called le Gayle.” A further record of 1461 indicates the use of “mereston” or moor stone for “24 large corbelles designed to carry the ends of the timbers of a floor in the tower.” Linking these together, it seems that the floor of the tower on the motte was completely renewed at this time. Next year, what constituted a complete kitchen range was constructed. Payments were made for “a great fire place (camini) called mantel, and two ovens within the said fire place in the castle kitchen called constabills ketchyn,” “mereston” being worked for the “corbelles,” “clavelles,” “dorestones,” “coynstones” and “vaultyngstones” for it. It was probably installed in the kitchen recorded in the Black Prince’s survey as being attached to the main hall. 1464 saw the purchase of 360 feet of “raggeston,” which was employed on “le copyng de le courtewall.”

In spite of all the repair work which had been carried out, the condition of the castle was still one of gradual deterioration. John Leland on his visit of 1540 observed that “much of the castle yet stondith……” which indicates that by this time some of it has already fallen down. In 1602, another antiquarian, Richard Carew, visited Launceston, and from his survey of Cornwall we can see which buildings of the bailey were standing at this time. He makes reference to both the halls for the shire assizes and the hall for the constable, and observed the county gaol in the bailey. The chapel is mentioned, though its condition is recorded as being “decayed.” A significant omission is any reference to the Earl’s hall, which we may assume to have long since vanished, considering the parlous state it had been in when the Black Prince became Duke of Cornwall.

Throughout the history of the construction and gradual decay of the castle, the town had been steadily increasing in size around it. Its rate of growth owed much to the presence of the castle, which through its administrative importance had made Launceston the principal town in the county. By the end of the 13th Century it had become encompassed by a wall with gates, a feature seen in no other town of Cornwall. In the neighbouring county of Devon, town walls were more frequently seen, and had been in evidence in particular at both Exeter and Barnstaple from very early times. By the time of Leland, it appears that the town wall was in a similar state of decay as much of the castle. “Dunhevet, otherwise Lawnston, is a walled towne, ny in cumpas a myle but now ruinous ….. Part of the castle standing north-west is parcel of the walle of the towne.” The wall was some 6 feet thick, and its top was apparently used as a promenade by the townsfolk. There were three gates in the circuit giving access to the town. The north and west gates have now vanished, and only the south gate remains, carrying with it a small fragment of the wall. It is basically a square tower with a central opening under a pointed arch. Above a passageway, which is partly barrel vaulted and partly flat roofed in timber are two rooms, above each other. The gateway, having at one time served as a prison.

THRICE BESIEGED

By the end of the 17th Century, the history of the castle as both a military and residential centre had ceased (although it was to play its role in the two world wars particularly in the second). During the Civil War when Launceston had supported the Royalists, the castle was three times besieged. Twice, in 1642 and 1644, it was captured by the Parliamentarians, only to be retaken shortly afterwards by the Royalists. The Crown finally lost it on February 25th 1646, when it was captured by an army under Thomas Fairfax. At the end of the war its condition was sufficiently bad for there to be no need to implement the standard Parliamentarian practice of slighting or dismantling it. A parliamentary survey of the time observed that the assize hall and chapel were ‘quite level with the ground’ and made reference to several habitations in the ditch outside the bailey. To replace the old assize hall, a new one was erected in the town, from which business of the county was conducted until being transferred to Bodmin in 1840. By virtue of its concentric defences on the motte, Launceston Castle represents a rather specialised version of the shell keep, but its basic development seems to be typical of a pattern which was occurring throughout England at the time. One can see parallels in Cornwall at Trematon and Restormel, both motte and bailey castles with 12th Century keeps. Only in detail do they differ. The fate of Launceston, as other Westcountry castles, rested largely in the hands of the reigning monarch, who was often also the Duke of Cornwall. As has been seen, in the times of Edward III and Richard I, the castle was maintained in reasonable condition, but later sovereigns did not show the same interest, and decay became inevitable.

In the time of Henry VIII, two coastal forts were constructed in Cornwall on the opposite sides of the Fal estuary at Pendennis and St. Mawes they were built high at the corner on a completely different principle to the old Norman strongholds. They acknowledged the inventions of gunpowder, and featured batteries from which cannon were fired. Considered in terms of this defensive strategy, Launceston Castle was obsolete. It had nothing more to offer.

As has already been mentioned previously, in 1834 after the construction of Western Road (which took much of the outer wall of the Castle), the ‘Witches Tower’ with its foundations weakened fell into the road after a severe storm one night. The town had requested that the Tower, which stood fifty to sixty feet high at the corner of Castle Dyke facing the White Hart, to be kept.

In 1838 the assizes and the seat of county government were moved from Launceston to Bodmin. With the removal of the assizes there came not only the destruction of the Guildhall but of the old Gaol as well. The latter building stood near the western gate of the Green and very close to the present day lodge.

Extract from Peter’s ‘History of Launceston 1895.

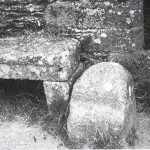

“ In August, 1764, a Mr Leach surveyed and made a plan of Launceston Castle and Park. A copy of this plan has lately been presented by C.L. Cowlard, Esq., to the Scientific and Historical Society. It is a poor work of art, but is very interesting as a key to the old town as it appeared one hundred and twenty years ago. On it is marked the prison house to which we have referred; and the surveyor has also noted what he calls ‘a remarkable stone, where ye Constable of ye Castle always delivers ye prisoners under sentence of death to ye Sheriff for execution. This stone was fixed in the road, which he names “a passage from the town to ye Castle”, but which we know as Castle Street, in front of the railings outside Mr. Dingley’s ‘Eagle House’, exactly on the line of the outer edge of the ancient ditch. Tradition asserts that the piece of granite now at the end of the seat within the Castle Green, by the Doomsdale wall, is the historical stone mentioned by Mr. Leach”.

“This gaol though built in the large green belonging to the old ruinous castle, is very small, house and court measuring only 52 feet by 44 feet, and the house not covering half that ground. The prison is a room or passage 23 ½ feet by 7 ½ feet, with only one window 2 feet by 1 ½ feet, and three dungeons or cages on the side opposite the window; these are about 6 ½ feet deep, one 9 feet long, one about 8, one not 5; this last for women. They were all very offensive. No chimney, no water, no sewers, damp earth floors, no infirmary. The court not secure, and prisoners seldom permitted to go out to it. The court not secure, and prisoners seldom permitted to go out to it. Indeed the whole prison is out of repair, and yet the gaoler lives distant. I once found the prisoners chained two or three together. Their provision was put down to them through a hole (9 inches by 8) in the floor of the room above [used as a chapel], and those who served them there often caught the fatal fever. At my first visit I found the keeper, his assistant, and all the prisoners but one (an old soldier) sick of it, and heard that a few years before many prisoners had died of it, and the keeper and his wife in one night. I learned that a woman who was discharged just before my first visit by the grand jury making a collection for her fees (13s 4d were required for a discharge) had been confined three years by the Ecclesiastical Court, and had three children in the gaol. There is no table of fees.”

“In 1779 five hundred pounds of the King’s Bounty was appropriated to this gaol. In a passage 5 ½ feet wide there were for men four new cells (8 ft by 6 ½, and 8 ft 4 ins high), a dayroom and a court. Over these rooms are the gaoler’s apartments. Adjoining is the old gaol, which is for women , and the court is made secure; no water. The mayor sends the prisoners weekly one shilling’s worth of bread; no memorial of the legacy in the the gaol.”

“The BOROUGH prison was for several centuries over the South Gate.”

A. F. Robbins:- The condition of Launceston Gaol deservedly occupied the attention of Parliament in 1778, early in which a petition, adopted at the Quarter Sessions held at Bodmin on the previous October 9th, was presented “setting forth, that the Common Gaol of the said County, for Criminals, is within the Castle of Launceston, and is at present in a very bad condition, – – – and that the said Gaol, and the town of Launceston, being situated near the Eastern Extremity of the said County, the Ease and Convenience of the Public would be best suited by an additional Gaol for Criminals being provided nearer the Centre of the said County,” and suggesting that such prison should be built at Bodmin. The Bill passed the Commons without opposition, and was equally successful in the Lords, the King’s assent to the measure, as far as it affected the Duchy of Cornwall, being signified during its progress. Up to that time the Duchy had had to bear the cost of repairing the prison, it not being the property of the County but really “the King’s Gaol at Launceston”, as it was termed as far back as 1524 in a “Testimonial of the Town of Bodmin against the Press;” and George the Third now gave two thousand pounds towards the building of the prison at Bodmin and five hundred pounds towards the enlarging of that at Launceston, on condition that the Duchy should be absolved from future liability for either.

In the year afterwards, out of the five hundred pounds of the King’s Bounty appropriated to Launceston, four new cells for men were built, while the older portion of the prison was reserved for women; but although the physical comfort of the inmates was now more attended by the erection of a pump in the men’s court and the better looking after of the drains, divine services on Sundays was dispensed with.

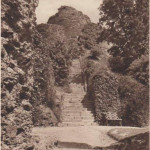

In 1838 the assizes and the seat of county government were moved from Launceston to Bodmin. With the removal of the assizes there came not only the destruction of the Guildhall but of the old Gaol as well. The latter building stood near the western gate of the Green and very close to the present day lodge. The widow of Christopher Mules was in possession of the old buildings until the end, and, as the Castle and its belongings were extra-parochial, the difficulty which had always been found in securing the payment of the rates from this property, extended to the process of evicting the last occupier. This eventually was achieved and in 1842 the Gaol was demolished. However by this time the Castle had been allowed to fall into a very bad state of repair and was stated to be a disgrace to all who had its management. Pigsties were abundant on its slopes, cabbage gardens occupied the space between ‘Sting-nettle Lane’ (which bounded the bottom of the mount) and the Castle Green, and a skittle-alley, appropriated to the customers of the ‘Exeter Inn, stood within the boundaries. Cock fighting was common on the second ring, this amusement being varied by pitch-and-toss and such like games. No steps led to the Keep. Which was inaccessible to any but speculative builders in want of good corner stones, and these were accustomed, crow-bar in hand, to use the Castle as their quarry, one result of which is especially obvious at the Green’s western gate, where the whole of the Polyphant stone forming the inner portion of the arch has been stripped away. It is said that the Queen of Portugal, travelling incognito, was passing through Launceston on her way to London shortly after Queen Victoria had ascended the throne, and while in the town she visited the Castle ruins. She was astounded at the state of disrepair and she informed the proprietor of the White Hart Hotel, Mr. James Eckley Prockter, that she should report the matter to Queen Victoria when she reached London. The Portuguese monarch was as good as her word, and Queen Victoria called the attention of the Duke of Northumberland, as Constable of the Castle, to the matter. The result was that the Duke had the entire area enclosed with the grounds being laid out as a pleasure garden from 1840 to 1842, at a cost to himself of £3,000.

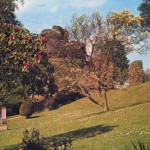

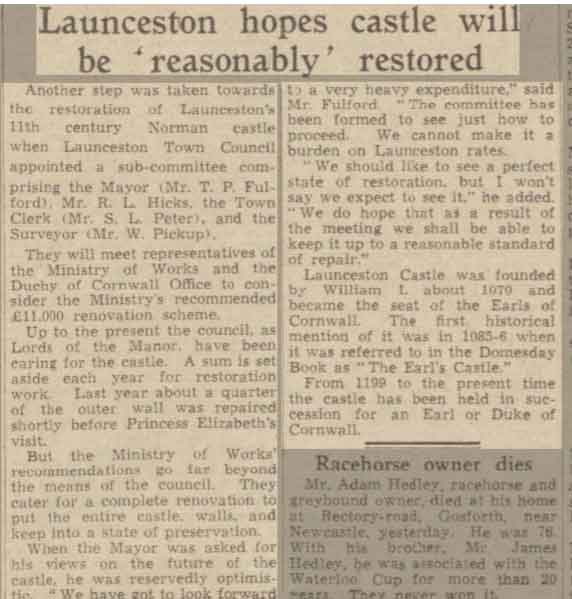

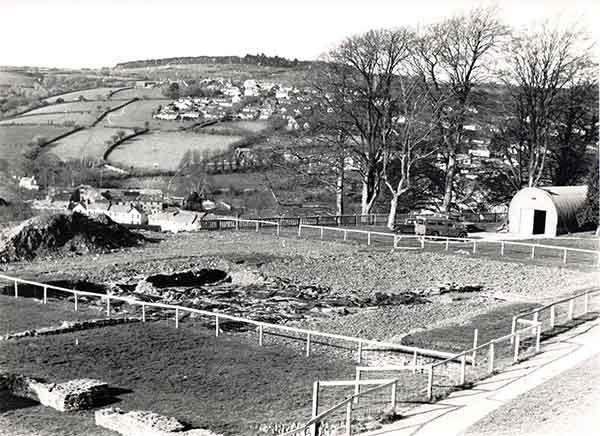

The grounds matured over the years providing a picturesque backdrop to the town as can be seen in the two photos above taken in 1894. The green having been flattened in the 1840 relaying, was used for social events with such things as Bazaars and fetes often being held. In 1901 the Town Council took out a thirty year lease from the Duchy of Cornwall and for the next 40 or so years the Castle Green laid open to numerous social events, none less than three separate Royal visits the last in November 1937 when King George VI came to collect the feudal dues. However, this all changed with the arrival of the Second World War, and the green was taken over by the US army who built a series of Nissen huts (below left and right) as a military hospital. After the war, the huts were taken over by the Air Ministry who obtained a 10 year lease on the buildings in 1945.

In 1951 the Ministry of Works took over the running and maintenance of the Castle and grounds from the Borough Council, thus alleviating the rising cost burden on Launceston’s rate payers. The Ministry of Works were keen for the removal of the Nissen huts, but with the Air Ministry not being able to find alternative premises the sub-lease was extended for a further twelve months. The site was evacuated in March 1956 and the green was returned to its formal glory. In 1957, the Ministry of Works let out for contract to E. Dennis and Son, of Camelford, the job of reconstructing 150 feet of the Castle’s boundary wall along St. Thomas road (New Road). They rebuilt this part of the wall to its original 12 feet in height and 2 foot 6 inches in depth. At the same time work was carried out on the foundations, or rather a lack of, where the reconstruction was built upon a 2 foot deep by 4 foot wide concrete footings.

Today the Castle and grounds are administered by English Heritage. Prince Charles was officially proclaimed Duke of Cornwall at Launceston Castle in 1973 (below). As part of his feudal dues there was a pair of white gloves, gilt spurs and greyhounds, a pound of pepper and cumin, a bow, one hundred silver shillings, wood for his fires, and a salmon spear.

Launceston Castle Gallery.

Visits: 252