.

For this story we have to go back to the year of 1864, when the Percy family sold the Werrington Park estate to Mr. Alexander Henry Campbell, a Manchester cotton merchant, who speedily intimated his intention of standing for the borough pf Launceston, and, though a Mr. John Cooke issued an address to the electors in the Liberal interest, no real opposition took place at the dissolution of 1865, and the new owner of Werrington was duly returned. Campbell, however, was a victim of the American Civil War and its effects of the cotton trade, and with serious finacial problems sold the estate to Mr. William Wentworth Fitz Dick, of Hume Wood, Baltinglass, Wicklow, for which county he was already representing in Parliament. As he was already in a safe seat, he had no need to represent Launceston, and so, on the resignation of Campbell in April, 1868, he put forward Mr. Henry Charles Lopes for the vacancy.

Lopes had won the confidence of William Dick (then Mr. Hume) in 1864 as counsel for him in a case of some delicacy. Lopes’s name was originally Franco, as he was the third son of Mr. Ralph Franco, who unsuccessfully contested Newport as a Whig in 1818, and who changed his name when he succeeded to the baronetcy of Lopes in 1831 on the death of his maternal uncle, the first baronet, Sir Manasseh (he was subsequently convicted at Launceston Assizes in 1818 for bribery at Grampound, and was sentenced to a heavy fine and a term of imprisonment). Henry Lopes (who was born in 1827, and was educated at Winchester and at Balliol College, Oxford) was called to the bar at the Inner Temple, in 1852, and travelled the Western Circuit, being appointed Recorder of Exeter in May, 1867. At the general election of November, 1868, he was for the second time returned for Launceston, and in the next June was raised to the dignity of a Queens Counsel.

In August, 1871, Mr. James Henry Deakin, of Manchester, purchased the Werrington Park estate from Mr. Dick, who had never liked Werrington. Deakin was an honoury lieutenant-colonel in the Lancashire volunteer, who, some twelve months later, communicated to Lopes, that he intended at the next election to represent Launceston, “either by myself or my nominee.” Lopes so resented the notice to quit that he subsequently published the whole correspondence in the ‘Standard.’ However, he was to take up the Conservative candidacy for Frome, for whom he was elected at the 1874 dissolution, and in November, 1876, he was appointed a Judge of the High Court of Justice.

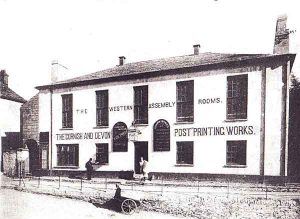

In September, 1873, Colonel Deakin issued an address to the electors of Launceston announcing his intention of contesting the borough when a vacancy should arise, and the dissolution of the next January gave him the opportunity he sought. The fact that Parliament was to be dissolved was made known on Saturday, January 24, and for a day or two it seemed as if the first election for Launceston under the Ballot Act would pass as quietly as had all its open-voting predecessors since 1835. But a change was soon apparent: on the Tuesday, Mr. William Derry, of Plymouth, intimated his willingness to come forward if the Liberals wished, while Mr. Henry Clark, Recorder of Tiverton, and brother-in-law of Mr. Lopes, also stated his interest. On the Wednesday it was seen that a contest was inevitable, for three would-be Liberal candidates had officially put their names forward. Mr. Herbert Charles Drinkwater, of Manchester, Mr. John Freeman Norris, barrister, of Bristol, and Mr. John William Batten, barrister, of London, who was professionally connected with the South Western Railway. They agreed to a public meeting to decide upon their claims which was held the same afternoon in the Western Subscription room (below left) with Herbert Drinkwater being the successful nominee.

A vigorous contest immediately got under way with Colonel Deakin quickly travelling from Manchester, where he had been assisting the Conservatives campaign within his own city, and when he reached Launceston on the Thursday he found that the extensive preservation of rabbits on his estate was being used as a political weapon to weaken his hold on his tenants. On the Friday the nomination took place, and the same evening, at a meeting at the Northumberland Arms (above right), the Colonel announced that each tenant was at liberty to destroy the rabbits on his farm. Herbert Drinkwater immediately denounced this as an act of bribery, and on Monday, February 2, when the polling was held, he served on every voting a formal notice that, if defeated, he should claim the seat on that ground. The eventual result was that 453 supported Deakin and 216 for Drinkwater. Within the statutory month, Drinkwater filed a petition against the return.

The trial took place in the Western Subscription room on May 5th and 6th, before Sir John Mellor, then Justice of the Court of the Queen’s Bench, Mr. Leresche and Mr. Bompass appearing for the petitioner, and Serjeant Parry and Mr. Edwards for the respondent; and on the afternoon of the second day the judge unseated Colonel Deakin, holding that the rabbit concession under circumstances was an act of personal bribery, but reserving the question of Drinkwater’s claim to the seat. This was argued the next month in the Common Pleas, before Lord Chief Justice Coleridge, Mr, Justice Brett, and Mr. Justice Denman, and judgement, at first reserved, was given against the petitioner and declaring the seat vacant.

The trial took place in the Western Subscription room on May 5th and 6th, before Sir John Mellor, then Justice of the Court of the Queen’s Bench, Mr. Leresche and Mr. Bompass appearing for the petitioner, and Serjeant Parry and Mr. Edwards for the respondent; and on the afternoon of the second day the judge unseated Colonel Deakin, holding that the rabbit concession under circumstances was an act of personal bribery, but reserving the question of Drinkwater’s claim to the seat. This was argued the next month in the Common Pleas, before Lord Chief Justice Coleridge, Mr, Justice Brett, and Mr. Justice Denman, and judgement, at first reserved, was given against the petitioner and declaring the seat vacant.

The Launceston Conservatives. In addition to presenting an address of sympathy to Colonel Deakin, took a practical method of showing their appreciation of him by signing a requisition to his eldest son, Mr. James Henry Deakin, junior, asking him to come forward. The Liberals immediately brought forward Mr. John Dingley, but at the same time nominated Mr. Hardinge Stanley Giffard, a prominent Conservative barrister who was then seeking a seat, and offered to allow him to be returned unopposed if the other side would withdraw Mr Deakin. The Conservatives declined and Mr. Giffard, having visited the town and learnt of the affairs, issued a statement asking all Conservatives to support their chosen candidate. This apparently they did not do, for at the poll on July 3rd, thirty-six fewer voted for him than had for his father in the February poll and seventeen more for Mr. John Dingley, while one solitary elector recorded his suffrage for Mr. Deakin.

From that time rumours were frequent that Deakin intended to resign, and Launceston electoral matters were kept before the public by the abortive attempt of Mr. Wykeham Martin, Liberal member for Rochester, to carry a bill in the session of 1875 for the remission of the disabilities entailed upon Colonel Deakin by the decision of the judge. In February, 1877, Deakin did resign, Sir Hardinge Giffard (as by this time he had become) immediately issued an address, and Mr. Robert Collier (a young barrister, and eldest son of Sir Robert Collier, who has embarked on a similarly hopeless contest thirty-six years previous) entered the lists on behalf of the Liberals. The polling took place on Saturday. March 3rd, when the Conservative majority, which had dwindled from 237 in February 1874, to 184 in the following July, was now lowered to 118, Sir Hardinge Giffard securing 392 and Mr. Collier 274. Sir Hardinge Giffard had Pendruccombe House built as his place of residence in Launceston. But the Deakin affair was the last time that Werrington was to have such a hold upon the Launceston electorate, and although the Williams family would offer themselves in future elections, democracy had truly taken hold.

CONTROVERTED ELECTIONS—LAUNCESTON—PETERSFIELD—BOSTON, 1874.

Visits: 260