In 1931 a grand pageant was organised for the town, with a full scale enactment of Launceston’s history. The pageant written by Mary Kelly, the daughter of the Revd. Maitland Kelly and his second wife Elfreda Blanche Carey, Mary Kelly wasn’t born in Kelly, but moved there as a young girl from her birthplace at Salcombe. Her father had become Squire of Kelly in 1900 as well as Rector; he was there for 37 years. Her mother had died when she was about three and after that she was looked after by an aunt and educated by a governess before going off to Surrey to school at the age of 16. Mary had founded the Kelly Dramatic Society (Kelly Players) and the Village Drama Society in Kelly, in 1919. Each year she wrote a religious play, at Ascension tide, developing its plot and characterisation around the personalities of local villagers. A stage was built in the tithe barn and gradually the dramas began to acquire a reputation for their directness and sincerity.

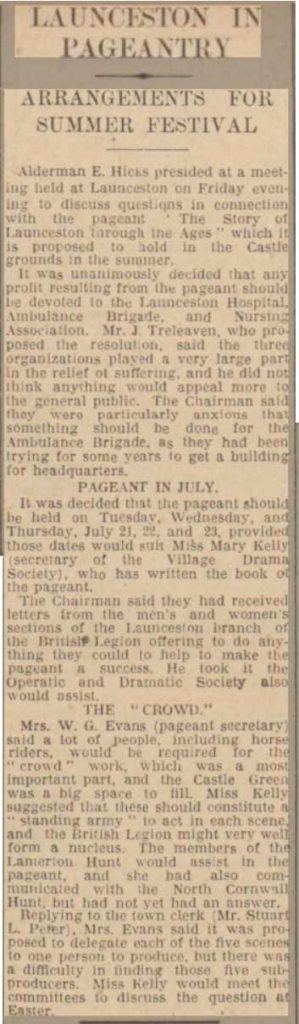

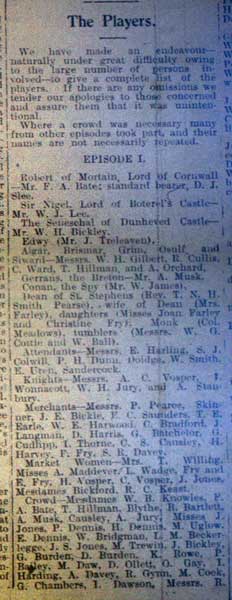

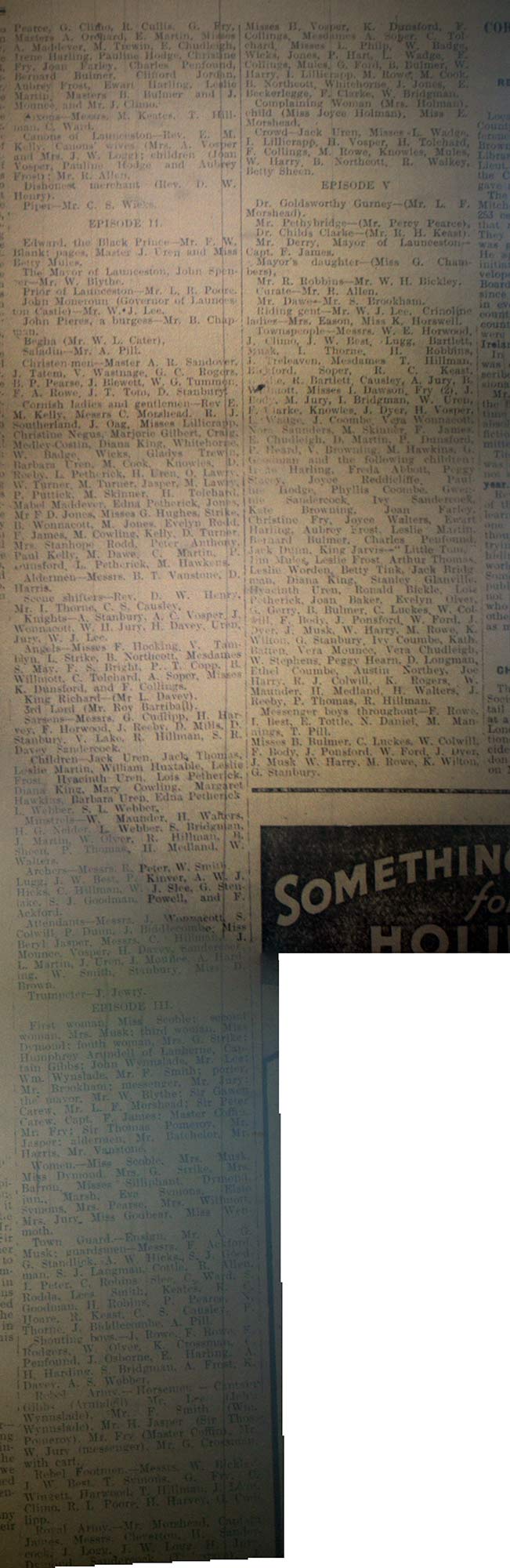

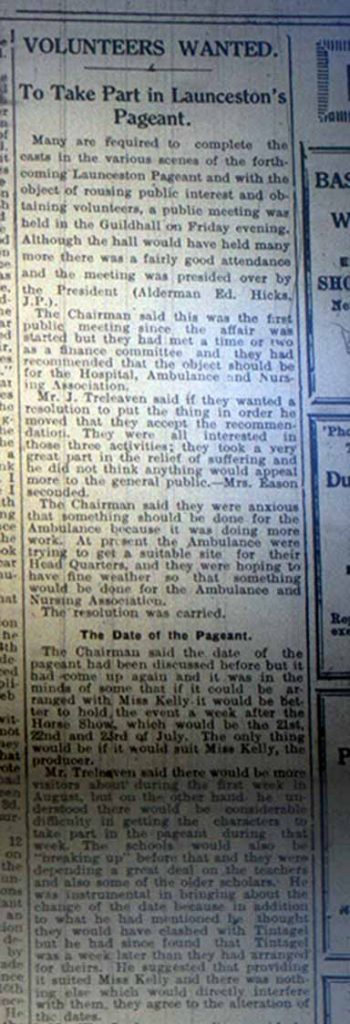

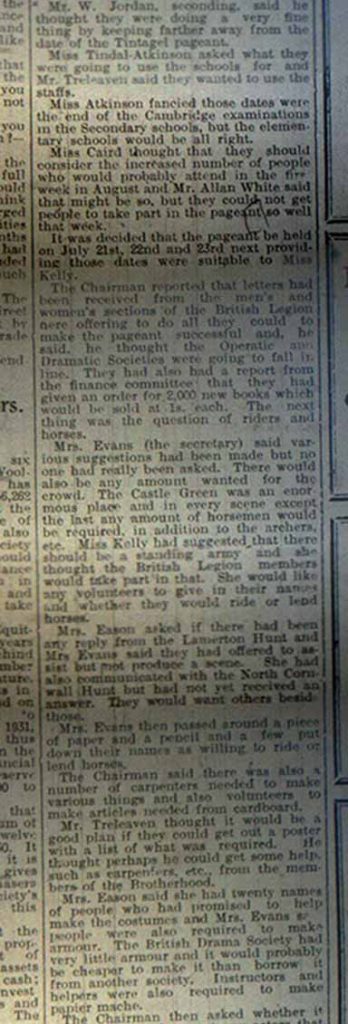

The Launceston pageant was in 5 episodes and depicted the historical events in the town between 1089 and 1862 and was produced by Mrs. W. G. Evans and performances took place on the Castle Green on July 21st, 22nd, and 23rd. It involved a cast of some 400 people. This is how ‘the Cornish and Devon Post’ reported the pageant on July 25th 1931 by Sydney D. Brimmell.

Once again, after an interval of but a few weeks – a short period in the passage of time, but one which seemed longer – I am given the opportunity and also the privilege of speaking to the people of my native town. Accustomed as I have been to doing this for so many years – with what measure of success is for others than myself to judge – it can readily be appreciated and realised with what pleasure I should seize such an opportunity, be the task grave or gay, sombre or coloured, for it brings me once more into that close and intimate touch with readers and friends whose name is legion which has been my happy experience for so many years.

The First Pageant — Why?

So, though the skies as I write are grey, and the sun so far has failed to break through the curtain of the mists of the morning, I start out in lightsome mood, with a feeling that, however much Statesmen may wrangle and pessimists may croak, all’s still well with the world, and that the best is yet to be. And that is just the spirit, just the mood, that I want to catch — any other would be inappropriate, and would strike a jarring note — for the story, the telling of which has been committed to my care, is that of Launceston’s first pageant. Launceston’s first pageant; I wonder why it should have been the first? That is the question I have been asking myself ever since Tuesday afternoon, when for two hours by the clock I sat and witnessed that wonderful revival of scenes dug up from the depths of Dunheved’s hoary and historic past, a revival that was as wonderful in its colour as in its realism. So thus it is that I have been wondering why in this age when the pomp and panoply of pageantry are seen throughout the length and breadth of the land, it is not until this year that Launceston should have drawn upon its rich and probably inexhaustible store of history to present such a series of living pictures as have been seen this week. It would be profitless to go on wondering for one might never probe sufficiently deep to find the reason; one can only feel glad that at last the thing has been done, and done moreover in such, a manner that the pride of Dunheved’s citizens in the achievement should have combined with it feelings of gratitude for those who have been mainly responsible for the production.

Bloody Slaughtering’s and Maidens’ Laughter.

This much by way of introduction and preface, foreword o, prologue; call it what you will, it is immaterial, for so convenient is our language in its synonyms that the meaning remains the same throughout. Let us return to the Castle Green, where so many generations of Launceston children have played their games, as so many generations yet unborn are destined still to play, and let us there see what Dunheved has to tell us through eight hundred years of its history. Eight hundred years. Yes a period approaching the threshold of ten centuries, for the roots of Dunheved are thrust far down into the soil of time. And therein probably lay the main difficulty which at the outset faced Miss Mary Kelly, to whom — and events have proved how wise was the decision — was entrusted the task of writing the Book of the Pageant, and of making herself responsible for its production. From the very outset Miss Kelly must have found it not a case of what to put in as of what to leave out; and therein lay the difficulty. She had — and it is certain that she did it with a twinge of regret — to omit the record of many stirring events, events which have left their impress for all time on the life of the town, but sorry as one must feel that this had to be done, one must at the same time congratulate her upon the selection she finally decided upon, a selection in which tragedy alternated with comedy, the clash of arms and bloody slaughtering’s with the lilt of maiden’s laughter and the guffaws of the men of the period. Yes, the Book of the Pageant was happily conceived, and the information which Miss Kelly gleaned from the borough’s local histories — with which the names of Peter and Robbins are so indelibly associated — was skilfully interwoven into a story which never flagged either in interest, education, or charm. And what a beautiful setting was provided for the story — the Green, the scene, as I have said of the frolics and games of Launceston boys and girls, as equally of happenings grim and sinister in times of old, and possessing a natural charm with, towering above it, the grey old ruin of which the borough is so justifiably proud. In such a setting where Nature so bounteously lent her aid, it was not difficult to stage a pageant, with the performers emerging from the grounds of the Castle on to the green sward that formed the stage, or through the two fine gateways north and south of the Green. Everything was appropriate in its antiquity, but modernity was brought to the aid of mediaevalism in the control of the entrances of the performers by means of a centrally situated microphone with relays to the various points of assembly. This, with these facilities at Miss Kelly’s disposal in her seat in front of the grand stand, there was never any perceptible halt or limp in the story, never any of those awkward pauses which tend to break the thread of the tale.

Above Spearmen from episode I. Above Roundhead army enter Launceston Castle.

The Opening Ceremony.

The time for the opening of the pageant draws near. The grand stand is rapidly filling, among those present being many a well known lovers pageantry, including Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch and Mr. Charles Henderson. It was a splendid representative attendance, and must have given much encouragement to the promoters of the pageant as well as to the performers, serving as some recompense for the many months of hard self-sacrificing work which they have put in. Golden sunshine bathed the scene in genial warmth, there was pleasing preliminary music from the radio orchestra, effectively concealed in the shelter, which had been transformed into an old-time castle entrance, and the auspices seemed to be — and were — of the happiest possible description when the opening ceremony was performed by Lord Vivian, who was accompanied by Lady Vivian, the Mayor and Mayoress of Launceston (Mr. And Mrs. J. Harvey), and members and officials of the Town Council.

The ceremony was commendably brief. There were just a few appropriate words from his Worship of Dunheved, who, in extending a welcome to Lord Vivian, said: “The Royal and Loyal Borough of Launceston is justly proud of its place in history. The walls of this ancient Castle which for a thousand years have watched over beloved town will today see again in pageant scenes which they witnessed hundreds of years ago. With our history is linked the history of many of the ancient Cornish families, and I have, therefore the greatest of pleasure asking your Lordship to open this pageant.”

I a happily expressed reply, Lord Vivian said they were gathered together to view some of the most interesting events in the history of the ancient borough of Launceston, formerly known as Dunheved. The pageant, he went on to say, was organised to raise funds for the Hospital, the Nursing Association, and St. John Ambulance Brigade, which he thought they would agree with him, were most worthy objects. He sincerely trusted that they might find that St. Swithan would not act up to his principles, and that they would be favoured with fine weather during the week. The organisation and hard work necessary for a pageant was very strenuous. And he was certain all the spectators and the parties interested would be very grateful to all those who had worked so hard to ensure success for the pageant. He would especially like to mention the name of Miss Mary Kelly, who was the founder of the Village Drama Society, and others who had worked so hard, but whose names it would be impossible to mention. Partly why he accepted their kind invitation to come there, of which he was very proud, was because they had a very active branch there of the British Legion, and he was glad to hear that they were responsible for one of the episodes in pageant. He thought the Mayor would be interested to see how his predecessors acted under certain critical times, and he would be able to form an opinion as to whether he would have acted the same as they did. “Also, I would like to say,” continued Lord Vivian, “that amongst us there are some who have to learn this history, and others who have got to refresh their memories. I am one of those of the first category and I shall be very interested in it. I feel that I ought to get on with my lesson, an I have, therefore, great pleasure in declaring the pageant open and in wishing it success.”

There remained to read a letter from Sir Donald Maclean, M.P. For North Cornwall, who wrote to the Mayor as follows: “I had looked forward with great pleasure to having the opportunity if being present at the Launceston Pageant. The international and financial situation is, however, so serious that I shall not be able to be absent from the House of Commons next week. I hope that fine weather will obtain throughout each day, but whatever the weather may be the pageant cannot fail to be a success, as there is no town in the country which, by virtue of its natural beauty and historic past, provides more opportunities for a memorable display.”

“CASTLE TERRIBLE.”

And so to the pageant itself, and the first scene of the five episodes in which it was divided. Dated 1089, this scene had as its theme the possession of the land, being shown in the pet sons of Conan, who comes of the ancient race of Cornwall, in Edwy, the representative of the conquering race of the English, and in the final possessors, the Normans. The descendant of all these races, Miss Kelly points out, may be seen in Launceston toady, and traces of the old bitterness are still to be felt in the district. The scene also shows the birth of Launceston as we know it, in the holding of the first market in Dunheved. The market was originally held at the old Launceston, on the opposite hill, St. Stephens, by Canons there, but the Conqueror decreed that all markets should be held in fortified places, and it was accordingly removed to Dunheved. The scene opens with the Seneschal, with a company of Norman soldiers, coming down from the Castle. Having drawn up his men on the Castle Green, in stentorian tones, he orders the opening of the gates, so that the merchants may enter for the market. “Be ready and prompt to deal with any disorder,” he commands, “for we are here set in the midst of two foes, the English and the Welsh.” The gates are flung open, and the merchants and people pour in. In garbs of varied hue and design they come running on to the Green, some with horses bearing packs of merchandise, one with a laden donkey. Their wares are unpacked, there is a babble of tongues as the buyers crowd around the stalls, and acrobatic tumblers lend added interest to the scene. Conan, a character represented with wonderful realism, understands the Welsh and the English tongues, and as he sells his fish, he is commanded by the Seneschal to move about among the people, “spark all that passes; come and tell me again that you hear; my Lord the Count will reward you if you are faithful.” With a smile of triumphant hatred on his face. Conan takes up his fish basket to return to the fair. Meanwhile, in the middle of the bustle of the market the Canons of Launceston with their wives and families, headed by their aged Dean, enter, and look around at the market sadly as they think of their lost privileges. Suddenly there is another blast on the horn and there is a sudden hush as the Seneschal proclaims that the Count Robert of Mortain will hold his Court of Pie Powder in the fair. Almost immediately the Count on horseback enters a proud, arrogant figure, clad in chain armour, accompanied by his knights, and takes his seat at the dias where her hears petitions and dispenses the rough and unmerciful justice — if justice it can be called – of the times, when men could scarce call their souls their own and when the bodies of their women were the sport and perquisite of the overlords. There was only one petition — that from the Dean touching the market which had been removed from St. Stephens. It was summarily and rudely dismissed, and the Dean leads his little flock away. A chapman struggling and shouting is then brought before the Count, accused of the offence of selling by short weight. A few words of evidence from a soldier and the sentence follows swiftly, “take him to the Castle and lop of the hand that cheats the King’s leiges.” Conan then comes forward, telling of how he has heard speech of a rising among the English, who are to make tryst at Druxton for a rising (below).

The little group of English are brought forward, there again the farce of a trial. Edwy of Polyphant denounces Conan, scourges the Normans in scathing terms, and calls down the curse of God upon King William and his Normans, as “land thieves and robbers, foul murderers, and profaners of Holy Church.” There is a terrified silence, the knights are about to rush upon Edwy, when they are stayed by Count Robert, who, quivering with rage, commands them to put up their swords: “You shall not foul them with the blood of a serf.” Turning to Edwy, he says, “You have spoken and by the Mass you shall speak no more.” He commands the soldiers to “take these men and hang them forthwith in the Castle Yard. So perish all the enemies of King William and of Count Robert of Mortain: and let all men know, that thus does Castle Terrible rule the land of Cornwall.” Up this note of tragedy the scene ends, and the market is brought to a close.

VISIT OF THE BLACK PRINCE.

The visit of the Black Prince, the first Duke of Cornwall to Launceston, on August 13th, 1353, forms the subject of the second episode, and provided one of the most spectacular scenes of the pageant. On this visit the Prince is “on leave” and out to enjoy himself, so the people of Launceston provide him with a show similar to those found in Froissart. Prior to the Royal arrival, the citizens arrange the scene and the items meanwhile the Mayor, a fat, fussy little man, bustles about form one place to another, giving contradictory orders and getting very much in the way. It was an excellent and well sustained piece of acting, and the scene throughout provided a touch of humour which came as welcome relief to the tragedy which had preceded it. One of the items is to be a carol by twelve angels of Heaven, in the Heavenly Jerusalem — a bevy of delightful maidens — but alas Begha, another fine character, who has been hurrying about for some time like a man distracted, tells the Mayor that though the angels are there, there is no heaven. “…I have made it with my own hands, and spangled it over with stars in the most seemly fashion… I know not where it is become. I laid it in the great chamber of the castle with my own hands,” In due course there follows the arrival of the Prince attended by the Prior of Launceston and John Moneroun, and accompanied by a large number of Cornish gentlemen with their families. This was a imposing and picturesque cavalcade, headed by the Prince, fair of hair and courtly of mien. The ladies were dressed in the rich attire of the period, one of them leading one of the greyhounds so favoured in those times. Children and pages completed and imposing spectacle, grouped to the right and left of the Prince, who had taken his seat after receiving the keys of the city of Dunheved, which he returned to the Mayor, “that you may keep it in trust for the King, as you have done heretofore. The “conceits and pastimes” that the burgesses have devised in honour of the Prince commence, the Royal Duke laughing heartily at the idea of angels without a heaven. Nevertheless, the angels sing and dance, and at the end their leader hands to him a jewelled chaplet, which he places on his head. He kisses the leader, and, seeing the rest edge up to him, kisses them all — having quite a good time, in fact — and the angels return to their “pageant” thoroughly pleased with them selves and doubtless with hearts all of a flutter — that is, if angels have hearts to flutter.

Led by King Richard, the Christian-men and then the Sarsens assemble for the next item — a mock fight. The latter are led by a very fat actor, almost completely wrapped in a blue drapery painted with stars. The mystery of the disappearance of Begha’s heaven is then solved. Begha falls upon the man who wearing his heaven. Pieres interposes, Begha calls the minstrels of St. Mary Maudlin to his aid, the Christian-men and Sarsens (below) rush into the fray from the other side, and for a few minutes there is a most strenuous conflict, in which blows are exchanged without restraint or reserve. Ultimately the combatants are paned, the cause of the unrehearsed uproar is explained to the Prince, who through it has seen the humorous side of the situation, and invites one and all to go to Paradise, within his castle, where there will be feasting and dancing all the day and all the night. Peace is restored, and there is an effective exit with the minstrels playing the company into Paradise.

THE CORNISH REBELLION.

The pageant goes on to 1549, to tell of the Cornish rebellion, a story of grim and stark tragedy, in which, though the leaders were mostly gentlemen, it was essentially a rising of the peasantry of Cornwall, ending as tragically as all other peasants rebellions. Humfrey Arundell, a member of the greatest family in Cornwall, was, almost against his will, obliged to join them, and after some desperate battles in Devonshire, he fled to Launceston, where, in a battle in the streets, he was overcome and taken prisoner by the men of Launceston. The Carews, arriving soon after, took him and the other leaders to Exeter, and they were subsequently taken to London, tried, and hanged at Tyburn. The scene opens with companies of women struggling in, one of them carrying a dear little infant. They demand from the Mayor news of their men in Arundell’s army, but he tells them “but few remain, and those will be here anon, for Master Arundell rides here in all haste,” Launceston, he says, cannot countenance rebellion, and if they will not go hence their sorrows may be increased. Boys rush in shouting that the army is approaching, the Mayor orders out the town guard, and through the gate the tattered weary remnant of the Cornish rebel army appears. The Mayor informs Arundell that Launceston will not have part or lot in the wickedness of rebellion, Arundell threatens to take the city, but the town guard rush upon the rebels and overcome them after a fierce struggle. There follows the arrival of the Royal Army, led by Sir Gawen and Sir Peter Carew, they are welcomed by the Mayor. Arundell and his men are led off prisoners, the Mayor counsels the women to return to their homes and nurture their children in the fear of God and in loyalty to the King. “Ees fay,” retorts one of the women — one of this flotsam and jetsam of sad and crushed humanity — “us must go home now, and rare up the chillun in hunger, and cold, and nakedness, that they may garnish gallowstrees when they’m grown to be men.”

SIR RICHARD GRENVILLE AND THE PRINCE.

This episode, dated 1646, provided another spectacular scene, with much of the richness of the uniforms and dresses of Royalty, army leaders, and people of high estate. The young Charles, Prince of Wales, is expected at Launceston, where he is to be met by Sir Richard Grenville, whose tyranny has roused some of the women to fury. The main incident of the episode is, of course, the coming of the Prince, who arrives at a time when the situation between Lord Goring’s men and a company of Grenville’s men has become strained. Goring’s men pull a man off a cart bearing a barrel of cider — a delightfully humorous character this — they briach the barrel and begin drinking at once, while others rob the market women of their baskets, kissing the girls and throwing the whole company into confusion. Grenville and Goring are at loggerheads when the Prince arrives, a regal young figure, with long dark curls and cape of royal purple blowing in the breeze. He is attended by a richly caparisoned entourage, the women tell him of the tyranny of Sir Richard, who refuses the Prince’s command to serve under Lord Hopton, whereupon the Prince commits him to prison, and cashiers him from the army. But this is too much even for the women, this sentence of imprisonment on Dick Grenville, and there seems likely to be a riot between Grenville’s men and Goring’s men. Even John Grenville, nephew of Sir Richard, who had come with the Prince, half draws his sword, but though the atmosphere still remains charged with tragic possibilities, Sir Richard quells the riot, and rides off with the Governor of the gaol. The people resume their lawful occupations, and on their dispersal, the Prince and John Grenville, friends once more, discuss a coming race between Piper’s grey mare and the Prince’s Sultan, and off to see the field where the race is to be run.

THE COMING OF THE RAILWAY.

In one stride the pageant passes over a period of 200 years to 1862, for the closing episode, the rejoicing at Launceston when the news was heard that the preamble of the Bill which was to give the borough its first railway had been passed, rejoicing which, Miss Kelly says, caused more emotion in Launceston than any other event of the last century. In this episode the “giants” of those days “came to life” once more. Mr. Richard Robbins, who fought so strenuously for the coming of the iron horse; Mr. Derry, the Mayor; the Rev. S. Childs Clarke, Headmaster of the Grammar School; the Rev. G. B. Gibbons, Perpetual Curate of Launceston; Mr. Dingley, Mr. Pethybridge, Dr. Goldsworthy Gurney, and others. There they were, with groups of the towns-people and their families — in one case a couple of toddling twins — with Mr. Robbins reading the good news in the paper of those days. All seem to be of one accord, but there is a fly in the ointment in the person of a Mr. Dawe, of Callington, who doesn’t believe in “this yer railway,” remarking, “if twas to go by Callington now, I wouldn’t have nort to say against en, but —.” And then he summarily closured by Mr. Robbins, who, impatient at the thought of opposition, to his pet scheme, and speaking with some heat, declares, “we have waited for nineteen years to get a railway, and if we listened to Mr. Dawe we should wait another nineteen years.” He tells of the prosperity of Launceston thirty years before, “and now the grass is almost growing there; and what can be done to remedy the decline?” “The railway; us must have the railway.” Shouts the crowd. Mr. Dawe subsides, and a messenger rides on with a telegram, telling that the Government have accepted the Bill. The crowd goes wild with excitement. Mr. Robbins and Dr. Goldsworthy deliver speeches, the Church bells start a-ringing, two different bands march on playing two different tunes as loudly as possible, Mr. Clarke promises his boys a holiday on the morrow, children dance and sing, ladies weep and chatter, and one and all are more or less beside themselves with joy. Such was the scene, and it was portrayed with remarkable attention to dress. There were the children running out from school, to the strains of “Boys and girls come out to play,” the youngsters wearing the quaint garb of the period. The gentlemen wore a variety of headgear which was the admiration of all beholders, while the ladies; God bless them — prinked and preened in the crinolines, with their frills, furbelows, and flounces of those discreet and proper Victorian days. There was, too, that little chap, Tom, so interested in his telescope, which he had saved up to buy so that he might see the stars. Finally, there was the last little episode of all, the cheers which were spontaneously given for Miss Kelly, who, it may be mentioned, in her Book of the Pageant, expressed her thanks to Mr. Charles Henderson and the Hon. Sir John Fortescue, who had helped her with information and criticism; also to Mr. J. A. Fuller-Maitland, who composed the tune of the Cavalier litany in the forth episode. She also mentions that the late Sir Alfred Robbins showed himself deeply sympathetic with the pageant, and was indeed engaged in writing the foreword at the time of his death.

Visits: 215