.

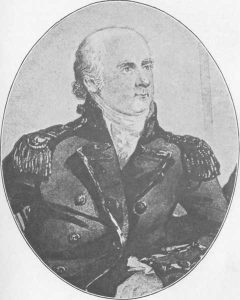

Philip was born on the 23rd of April 1758 to Philip and Utricia (nee Gidley) King at No. 5 Southgate Street, Launceston. His father was a Draper but died in 1764 with Philip junior just 6 years old. He joined the Royal Navy at the age of 12 as captain’s servant and was commissioned as a lieutenant in 1778. King served under Arthur Phillip who chose him as second lieutenant on HMS Sirius for the expedition to establish a convict settlement in New South Wales. On arrival, in January 1788, King was selected to lead a

small party of convicts and guards to set up a settlement at Norfolk Island, leaving Sydney on 14 February 1788 onboard HMS Sirius. On 6 March 1788, King and his party landed with difficulty, owing to the lack of a suitable harbour, and set about building huts, clearing the land, planting crops, and resisting the ravages of grubs, salt air and hurricanes. More convicts were sent, and these proved occasionally troublesome. Early in 1789, he prevented a mutiny when some of the convicts planned to take him and other officers prisoner, and escape on the next boat to arrive.

Whilst commandant on Norfolk Island, King formed a relationship with the female convict Ann Inett – their first son, born on 8 January 1789, was named Norfolk. (He went on to become the first Australian-born officer in the Royal Navy and the captain of the schooner Ballahoo.) Another son was born in 1790 and named Sydney.

Following the wreck of Sirius at Norfolk Island in March 1790, King left and returned to England to report on the difficulties of the settlements at New South Wales. Ann Inett was left in Sydney with the boys; she later married another man in 1792 and went on to lead a comfortable and respected life in the colony.

King, who had probably arranged the marriage, also arranged for their two sons to be educated in England, where they became officers in the navy. Whilst in England King married Anna Josepha Coombe (his first cousin) on 11 March 1791 and returned shortly after on HMS Gorgon to take up his post as Lieutenant-Governor of Norfolk Island, at an annual salary of £250. King’s first legitimate offspring, Phillip Parker King, was born there in December 1791, and four daughters followed.

During his twenty months absence, the island had been under the command of Lieutenant-Governor Robert Ross but Ross was not an easy commandant and convicts, settlers, soldiers and officials had become discontented under his rule. King found ‘discord and strife on every person’s countenance’ and was ‘pestered with complaints, bitter revilings, back-biting’. Tools and skilled labour were both very short. Thefts were common and there was still no criminal court on the island, despite the representations he had made in London on the need for better judicial arrangements. However, King’s able and enthusiastic guidance helped to improve conditions. The regulations he issued in 1792 encouraged the settlers, who were drawn from ex-marines and ex-convicts, and he was willing to listen to their advice on fixing wages and prices and other things. By 1794, the island was self-sufficient in grain and had a surplus of swine that it could send to Sydney. The numbers ‘off the store’ were high and few of the settlers wanted to leave, but unfortunately, King had had no success with the growing of flax that so interested the British government. In February 1794, King was faced with unfounded allegations by members of the NSW Corps on the island that he was punishing them too severely and ex-convicts too lightly when disputes arose. As their conduct became for mutinous, he sent twenty of them to Sydney for trial by court-martial. There Lieutenant-Governor Francis Grose censured King’s actions in going to New Zealand without first informing him, something with which Portland the new secretary of state in London later concurred and issued orders that gave the military illegal authority over the civilian population. Grose later apologised, but conflict with the military continued to plague King.

Suffering from gout, King returned to England in October 1796, and after regaining his health, he resumed his naval career. Phillip had wanted King to be appointed the governor of New South Wales in 1792 and had continued to advocate King’s cause after Hunter had been preferred in 1794. In January 1798, it was decided that he should return to New South Wales with a dormant commission as Governor-General to succeed Hunter in the event of the latter’s death or absence from the colony, though at that time there was no question of Hunter being recalled. The commission was issued on 1 May. However, King was delayed in England for a further year and when he finally sailed in a whaler, the Speedy on 26 November 1799 the situation had changed and he carried the dispatch recalling Hunter. King became Governor on 28 September 1800. He set about changing the system of administration and appointed Major Joseph Foveaux as Lieutenant-Governor of Norfolk Island. His first task was to attack the misconduct of officers of the New South Wales Corps in their illicit trading in liquor, notably rum. He tried to discourage the importation of liquor and began to construct a brewery. However, he found the refusal of convicts to work in their own time for other forms of payment, and the continued illicit local distillation, increasingly difficult to control. He continued to face military arrogance and disobedience from the New South Wales Corps. He failed to receive support in England when he sent an accused officer John Macarthur back to face a court-martial.

King had some successes. His regulations for prices, wages, hours of work, financial deals, and the employment of convicts brought some relief to smallholder’s, and reduced the numbers ‘on the stores’. He encouraged the construction of barracks, wharves, bridges, houses, etc. Government flocks and herds greatly increased, and he encouraged experiments with vines, tobacco, cotton, hemp, and indigo. Whaling and sealing became important sources of oil and skins, and coal mining began. He took an interest in education, establishing schools to teach convict boys to become skilled tradesmen. He encouraged smallpox vaccinations, was sympathetic to missionaries, strove to keep peace with the indigenous inhabitants, ordered the printing of Australia’s first book, New South Wales General Standing Orders, and encouraged the first newspaper, the Sydney Gazette. Exploration led to the survey of the Bass Strait and Western Port, and the discovery of Port Phillip and settlements were established at Hobart and Port Dalrymple in Van Diemen’s Land.

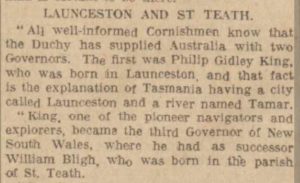

While still aware that Sydney was a convict colony, he gave opportunities to emancipists, considering that ex-convicts should not remain in disgrace forever. He appointed emancipists to positions of responsibility, regulated the position of assigned servants, and laid the foundation of the ‘ticket of leave’ system for deserving prisoners. Although he directly profited from a number of commercial deals, cattle sales, and land grants, he was modest in his dealings compared with most of his subordinates. The increased animosity between King and the New South Wales Corps led to his resignation and replacement by another Cornishman the infamous William ‘Captain’ Bligh in 1806, and he returned to England. Here his health failed and he died on the 3rd of September 1808. He was buried in the churchyard of St Nicholas, Lower Tooting, London.

Although he worked hard for the good of New South Wales and left it very much better than he found it, the abuse from the officers harmed his reputation, and illness and the hard conditions of his service eventually wore him down. Of all the members of the First Fleet, Philip Gidley King perhaps made the greatest contribution to the early years of the colony.

He is best remembered today for the naming of Launceston’s sister town (City) in Tasmania which was initially was called Patersonia, however, Lt. Col. William Paterson, the commandant of the British garrison there later changed the name to Launceston in honour of Philip, as the new New South Wales Governor. There still survives a tiny hamlet of Patersonia which is just 8 miles north-west of Launceston.

Visits: 86