With thanks to Allan McInnes.

Thomas was born in 1812 to Thomas and Sarah (nee Prockter) Ching at Launceston. His father was a wine merchant and chemist and his brother, John, was to be a future mayor of Launceston. After his public school education Tom, as he was known, set out for a career at sea. At the age of 21 years he was diligently studying his way towards becoming a chief mate and, eventually, a master. It was at this time that he joined the crew of the 313 tons barque ‘Charles Eaton’ as a midshipman.

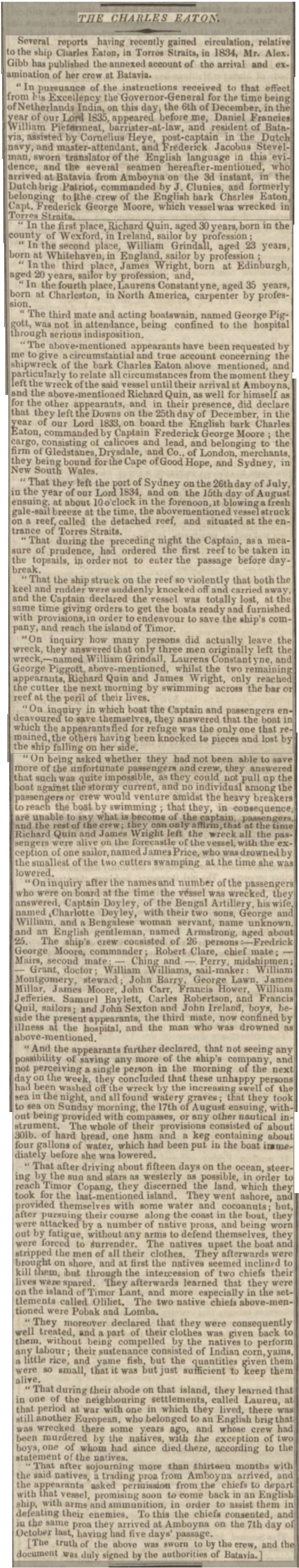

The ‘Charles Eaton,’ commanded by Frederick George Moore and owned by William Gladstone of London, left England on December 25th, 1833 carrying a cargo of calicoes and lead bound for Canton, China.The ships company of 26, as well as Captain Moore and Tom Ching, consisted of first, second and third mates, surgeon, carpenter, steward, two midshipmen, 13 seamen and two cabin boys, John Sexton and John Ireland.

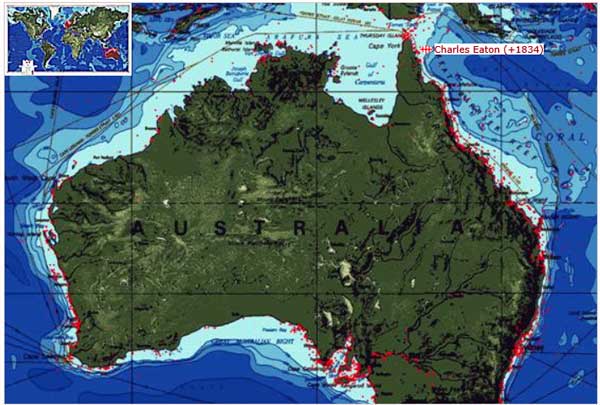

The ‘Charles Eaton’ made the port at Cape of Good Hope for fresh water and supplies and reached Hobart Town on June15th. She arrived at the port of Sydney, Australia on July 13th, 1834.

The ship then left Sydney on July 29th, along with the schooner ‘Jane and Henry’ commanded by Captain Cockburn, heading for Canton with six passengers. Her passengers were Captain D’Oyly of the Bengal Artillery, his wife Charlotte, their two youngest sons George and William aged seven and two, their Indian nurse and a Mr. Armstrong, a London barrister.

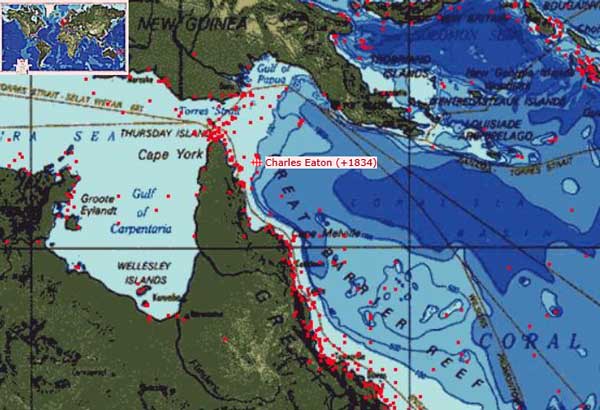

However on August 15th, the ships parted company when they were hit by a gale whilst in the ‘Torres Straits.’ The schooner managed to safely ride out the storm and on August 27th, it fell in with the ‘Augustus Caesar’ commanded by W. Wiseman outside the Barrier Reef. Both ships navigated through the reefs and anchored off ‘Double Island’ just a few miles from ‘Thursday Island.’ Three crew members of the Augustus landed and discovered wreckage of a ship including casks marked ‘Charles Eaton.’ The three men continued their search around the island but found no sign of the main wreckage, but they disturbed some natives who ran into the bush. A recent fire made from where the natives ran from was discovered, near where were human bones. The three crew men returned to the Augustus with a keg and other pieces of wreckage which convinced Captain Wiseman that the ‘Charles Eaton’ had been wrecked and possibly some distance to windward of ‘Double Island.’

When the ‘Jane and Henry’ and ‘Charles Eaton’ parted company in the confusion of the gale, the latter’s captain attempted to bring his ship into a favourable position within the straits, but the weather was so bad the visibilty so poor that it made it impossible to observe his latitude. As a matter of prudence and wishing to avoid entering the passage before daybreak, Captain Moore ordered the first reef to be taken in the topsails. On the next day the ‘Charles Eaton’ headed for the entrance and at about 10 o’clock in the morning of August 15th, with the breeze blowing strongly, the reef suddenly appeared ahead. An attempt was made to tack, but she would bot stay. The ship was immediately hove up in the wind, with both anchors let go and the cables paid out to full length but they found no hold on the ground. She struck the ‘Great Detached Reef’ (which is part of the outer Barrier Reef situated at the entrance of Torres Straits and approximately 40 miles east of the Sir Charles Hardy Islands). This impact was so severe with both the keel and rudder being torn off and carried away, and two of her boats were wrecked.

Captain Moore declared that the ship was lost and ordered that the lifeboats be launched, gathering as much provisions as was possible with the aim of reaching the island of ‘Timor’.

There were four lifeboats on the ‘Charles Eaton’; a long boat, a dinghy which were both smashed and two cutters. The smaller cutter was lowered but was immediately swamped and seaman James Price drowned. Soon after, three of the crew, third mate, G. Piggott, carpenter, L. Constantine and seaman W. Grindall put sails, provisions, water and all the carpenters tools in the last remaining and larger cutter and launched her. The three crewmen stayed near the wreck for the rest of that day and the following night, keeping their position by the use of their oars. The next morning two seamen, R. Quinn and J. Wright, swam out through the dangerous sea and joined the cutter.The crewmen were unable to pull up to the ‘Charles Eaton’ due to the strong current, and although when the two further seamen had left the ship, all aboard were still alive, no-one further would venture the heavy breakers to reach the lifeboat. By Sunday the 17th, as there was no sign of life aboard the ‘Charles Eaton,’ the men concluded that all had been washed off and had drowned during the night and so they set off for ‘Timor.’

Using the sun and the stars by which to navigate, they reached the eastern part of ‘Tenimber Islands’ in 15 days. They went ashore, replenished their water and collected coconuts. On resuming their course along the coast they were attacked by a number natives in their proas (a type of multihull sailing vessel). Exhausted and without any weapons, they were forced to surrender. Brought on shore and stripped of all their clothes, but for the intervention of two native chiefs, Pabrok and Lomba, they would have been killed. The captors took them to their nearby village of ‘Olilet’ where the prisoners were kept for over a year. During their imprisonment they were treated well with some of their clothes were returned and were fed on small quantities of corn, yams, rice and fish. The ‘Olilet’ natives were at war with a neighbouring tribe from ‘Laorau.’

In September 1835, a trading proa arrived from ‘Amboyan’ and the prisoners sought permission from the native chiefs for their freedom, promising that they would return with arms and ammunition to assist them in their war. They were granted their freedom on this promise and five days later they arrived in ‘Amboyna’ finally reaching ‘Batavia, where on October 7th, 1835 their sworn depositions were formally taken down.

However, their version of events were to be challenged the following year when the Colonial Schooner ‘Isabella’ was fitted out and prepared for a mission to locate the survivors that were rumoured to be still alive. A crew of five officers and 25 men were recruited for what was anticipated to be a four month search. Charles Morgan Lewis volunteered as Master with Phillip Parker King as his Captain. The information they were working on was quite sparse and conflicting. The Batavia depositions claimed there were no survivors, whilst that of William Carr, Commander of the Ship ‘Mangles,’ stated that there were further survivors, namely a little European boy, being held captive on ‘Murray’s Island’ in the ‘Torres Straits’. Another statement claimed the ‘Charles Eaton’ had been wrecked near ‘Sir Charles Hardy’s Island,’ which was close inshore and far from the outer reef’s. With fortuity as it turned out, the expedition began with ‘Murray Island.’

It was on June 19th, that ‘Isabella’ dropped anchor off the northern side of the Island. As she was anchoring, natives congregated on the sea shore and quite clearly among them was a naked white man. As the natives launched their canoes, discreet defensive precautions were taken on board the ‘Isabella’. With these concealed, the ‘Isabella’ outwardly displayed a friendly and disarming front. Four large 40ft canoes came out, each containing 16 men. They were fitted with outrigger and with a large platform amidship on which was a variety of goods for trade. On nearing the ‘Isabella’ they called out “poued, poed” meaning “peace, peace”. They held up the items of trade and asked for “toree and tooleck”, knives and axes. As many had already had contact and traded with the ‘Murray Islands’ natives, their language was not entirely unknown, but who through signs, made in the hope that the natives would bring out the white man to interpret for them. The ruse failed, so axes were displayed tantalisingly as baits. Then signs by Lewis asked for the white man to be brought out, again they declined. A stand off ensued until the natives realised that no trading was to be completed until the white man was brought aboard and so they sent a canoe to bring him aboard. Once he was near, Lewis saw that the white man was a youth of about 17. The youth looked both excited and fearful. Lewis ordered silence among everybody and not a word was then uttered by either seamen of the natives. Lewis then asked the dazed looking youth in what ship he had been wrecked, his reply – the ‘Charles Eaton!’ Lewis then asked just how many more survivors were there – one, a child of about four or five. Lewis asked the youth to step forward in the canoe, which he did, but the natives, wanting a ransom, held him back, refusing him to board the ‘Isabella’ until they received some recompense. Lewis allowed for some axes to be passed over so that the exchange could be made.

With the tense situation over for now, Lewis held back from making further enquiries, deciding to win the trust and friendship of the natives. Lewis gave permission to trade and a flurry of friendly bartering commenced. With the trading going on in the background, Lewis turned to the youth who was the cabin boy John Ireland. Ireland told Lewis that he had been treated well by the natives adding that one in particular was he indebted to for his life and he was called Duppar. Lewis realised that this was an opportunity to gain more trust from the natives and immediately invited Duppar on board and rewarded him for his deeds by showering him with linen and presents. Lewis then enquired about the other survivor, who it turned out to be young William D’Oyly. The natives informed him that he was on the other side of the island and could not be produced that afternoon, but they promised to bring him in the following morning. Lewis sensed that they were reluctant to part with D’Oyly, and fearing they might conceal him, ordered all bartering to cease until he was given up. On the arrival of the following morning, five canoes came back out to the ‘Isabella’ to what the natives thought would be a continuance of the previous days trading. However, they hadn’t kept their promise to bring along the child so again Lewis forbade any trading. There was a real reluctance on the part of the natives to give up the child, yet their yearning for the axes proved to Lewis that he could strike a deal without the need for force. But the standoff continued for some time and so Lewis decided to take a sterner stance. He ordered for the ports to be opened and the guns run out, Lewis then stated that force would be used. This show of strength cleared the minds of the natives, who now realised that Lewis meant business, so a canoe was sent off back to the shore and returned very soon with the message that they would exchange the child for ‘Toree.’ Although the natives prevaricated in wanting payment first, after Lewis again stated that no trading would continue, they soon relented. Shortly after a group of about 100 natives gathered on the shore with a young and naked William D’Oyly in their midst. They stayed on the shore for several hours in conversation and this continued until the late afternoon when eventually the child was brought out with a native called Oby, who like Dubbar had for Ireland, had taken care of William. Likewise, Lewis acknowledged Oby by showering him with gifts.

It was several days before Ireland was able to give an account of what had happened, for he had not use the English language for nearly two years and he mixed his speaking with the Murray Islanders with English. When he started to tell the story he immediately contradicted that of the other survivors. He stated that after Quinn and Wright joined the other three in the cutter they had refused to take any more; even though six of the crew had made their way over the reef that next morning and wished to join them. The cutter bore away and never returned. Captain Moore made a raft which took seven days to build, and during this time they managed to distill some sea water by the aid of the ship’s coppers, and a leaden pipe which they placed on the raft with some beer and pork. Whilst the raft was being made they were rationed to two glasses of distilled water a few pieces of biscuit per hear per day.

With the raft finished, they launched it but soon found that it didn’t have enough buoyancy to hold them all. In an attempt to balance the raft they threw out into the sea all the accumulated rations but to no avail, so they returned to the wreck leaving just Captain Moore, Mr. Grant the surgeon, the D’Oyly family, Mr. Armstrong and two seamen on the raft now moored up along side ‘Charles Eaton,’ and settled down for the night. The next morning, those that had rested upon the wreck found that the raft was gone after its tethering rope had been cut. The remaining survivors, including Tom Ching, set to in making a second raft which took a further seven days to complete by which time the ‘Charles Eaton’ was now being breached at high water and was very close to breaking up. Having boarded the raft made very little progress traveling, or drifting as it was in truth, at less than a mile an hour.

After several days of ‘drifting’ and with very little in food they passed by several islands, exhausted and with little strength left it the islands were out of their reach, but all of a sudden they noticed a canoe heading towards them containing about a dozen natives who as they approached held out their arms to show they had no weapons. On reaching the raft the natives acted very peacefully and invited the survivors in to their canoe. Being mis-trustful the crew were somewhat hesitant even though their situation was quite dire. It was Tom Ching who took the lead by saying “he would join the natives as he should then have a better chance of getting to England,” the rest of the crew followed his lead at in the late afternoon the natives rowed back to the shore, to a sandy bay that the natives called ‘Boydan.’ On landing the fatigued, starving survivors attempted to find food and water, but it was as much for them to crawl and so just fell to the ground in despair. It was then that the attitude of the natives changed, for now they just stood grinning and laughing to each other in what Ireland described as ‘in the most hideous manner’ and it soon became evident that they were exulting in the anticipation of their murder. Realising the situation, the first officer, Mr. Clear calmly read prayers to his fellow survivors and urged them to be resigned to their fate, after which commending themselves to the protection of the Almighty, they lay down, worn out, exhausted and unable to offer any resistance and fell asleep. Ireland was awoken by a loud shout and in looking up witnessed the beginning of the massacre with the natives attacking his fellow survivors with clubs and as he put it ‘dashing their brains out.’ Tom Ching was the first to die quickly followed by Perry and Mayer, the second officer. The last to meet his fate was Clear, who in an attempt to escape to the canoe was overtaken and killed by a blow to the head. It was now just Ireland and another boy called Sexton left and Ireland described his escape;

“An indian came to me with a carving knife to cut my throat, but as he was about to do it, having seized hold of me, I grasped the balde of the knife in my right hand and held it fast struggling for my life. The indian then threw me down, and placing his knee on my breast tried to wrench the knife from out of my hand, but I still retained it, although one of my fingers was cut through to the bone. At last I succeeded in getting uppermost, when I let go and ran into the sea, and swam out, but being much exhausted, and the only chance for my life was to return to the shore, I landed again fully expecting to be knocked on the head. The same indian then came up and with an infuriated gesture, and shot me in the right breast with an arrow, and then in a most unaccountable manner suddenly became quite calm and led or dragged me to a little distance and offered me some fish and water, which I was unable to partake of.

Whilst struggling with the indian I observed Sexton who was held by another, bite a piece of his arm out, but after that know nothing of him, until I found his life had been spared in a manner similar to my own. At a short distance off, making the most hideous yells, the other savages were dancing round a large fire before which were placed in a row the heads of their victims; whilst their decapitated bodies were washing in the surf on the beach, from which they soon disappeared,”

The next day, the natives collected together all the heads, and canoed to another island called ‘Pullan’ where the women lived. It was here that Ireland first saw the two D’Oyly children. George D’Oyly told him that the first raft had drifted onto ‘Boydan’ and that all but himself and his brother had been instantly murdered. Ireland could see the skulls of those from the first raft which were suspended by a rope to a pole that was struck up near the huts of the women. The natives would dance around these every night and morning, making furious gestures whilst screaming. As it transpired, this group of natives numbering around 60, made ‘Pullan’ their home during the fishing season, and after remaining there for about two months they separated, with one party taking Ireland and the infant D’Oyly with them. This party continued their channel hopping northwards for several weeks until they arrived at ‘Darnley Island.’ They stayed here for about two weeks before embarking again to an island near Aureed Island. This is when ‘Duppar’ of the Murray Islands came onto the scene. Duppar had heard of the two white boys being kept in captivity at Aureed, and so along with his wife, Pamoy, they embarked in a canoe for the purpose of obtaining them, taking fruit to trade. The eventual price for the two boys being a bunch of bananas each. Both boys were taken back to the Murray Islands and that is where they remained until the rescue.

With Ireland and the young D’Oyly duly rescued, the search then began for Sexton and the other D’Oyly boy. After Ireland informed Lewis that the natives of ‘Darnley Island’ often visited the island where the survivors were massacred, to which Lewis decided to visit. On arrival, the canoes came out to trade. Through Ireland they were informed that no trading would take place until the white men had been given up, but the natives denied that they were on the island. The ‘Isabella’ stayed anchored off ‘Darnley’ for several days replenishing its water supplies and also sending search parties onto the island. Part of one of the sails used on the first raft was found, and one of the chiefs was wearing the tattered remains of Tom Ching’s shirt with his name, T.P. Ching, clearly embroidered on the collar, but the natives continued their insistence that there were no white men being kept captive on the island. Through sheer persistence Lewis managed to find out from a group of natives that the heads of the white people who were murdered at ‘Boydan’ were preserved on ‘Aurees Island’ and that the natives danced around them every morning and night whilst expressing their delight by screaming, yelling and making horrid gestures. They also stated that there were no more captives alive, confirming that bot Sexton and the other D’Oyly boy had been murdered. This ‘Darnley’ group also gave the grisly details that the murderers had eaten the eyes and cheeks of their victims to excite them and forced their children to join them in this order to make them brave.

Lewis then sailed for ‘Aureed,’ calling and searching at islands as the ship made its way. At ‘Keats Island,’ Lewis became more aggressive after not being satisfied that the natives were telling the truth, but after ordering 18 men out of the boats armed with muskets, fixed bayonets and cutlasses, but the natives, although terrified, still insisted that there were no skulls or white captives on the island. However they did tell Lewis that the inhabitants of ‘Aureed’ had left their island on hearing that the ‘Isabella’ was on her way.

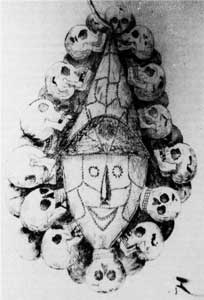

It wasn’t until July 25th, that the ‘Isabella’ anchored off ‘Aureed Island.’ But as the ‘Keats’ natives had stated, the inhabitants had made good their departure, for all that Lewis and the search party found were several dogs howling on the beach. The search of the area commenced and when they arrived at a group of trees they found an avenue lined on both sides by shells painted red lining to a dilapidated low thatched shed. On entering the shed, Lewis found the long searched for skulls, which had been systematically arranged around a large figure, the central piece of which was a tortoiseshell smeared in red. Being between four to five feet in length by about two and a half feet wide, the figure had a semi-circular projection standing out from the forehead which was also made of tortoise shell fancifully cut and ornamented with feathers. In the centre of the figure from the projection upwards was a small bundle of broken arrows bound together. The eyes of the figure were detached and made from a silvery shell like pearl shell. The face was surrounded by shells methodically arranged and stitched together with small cord of native manufacture but the skulls were tied to the outer perimeter of the figure by rope of a European origin. Again the skulls were arranged in symmetry. There were clear signs of violence upon the skulls with several being cracked or partially knocked in, whilst others bore deep incisions. Some even had hair driven into the indentations. The skulls of two females and two children stood out, and attached to one was long sandy hair. Ireland stated that the natives on ‘Murray Island; also had a similar figure which they brought out for feasting days and for general rejoicing.

The shed was unroofed so as not to damage the figure, which was taken out in its entirety and transported to the ‘Isabella.’ So incensed at what he found, Lewis ordered that everything should be destroyed on the island including the remnants of the skull house which was set alight along with everything else on the island. All the trees including the coconut trees were cut down and destroyed. The final act for Lewis was the renaming of the island to ‘Skull Island!’ One final search was made before their departure which uncovered two more scorched European skulls.

After a journey taking in other islands, the ‘Isabella’ arrived back in Sydney on October 12th, 19 weeks and 3 days after she had started the mission. Of the 45 skulls found on ‘Aureed Island,’ seventeen had been identified as European and under the direction of Governor Bourke they were given a Christian burial in the Sydney cemetery in Devonshire Street. A memorial stone commemorating the catastrophe was erected. In 1904 the cemetery was resumed for the construction of the Central Railway Station, the skulls and monument were removed to the Bunnering cemetery at Botany Bay.

Charles Lewis escorted the young William D’Oyly back to London where the boy was reunited with his family and taken in by his mothers sister Mrs. Bayley of Stockton-on-Tees. He was educated at Stockton and then went into the military and was serving in India when he contracted Cholera and died in 1852.

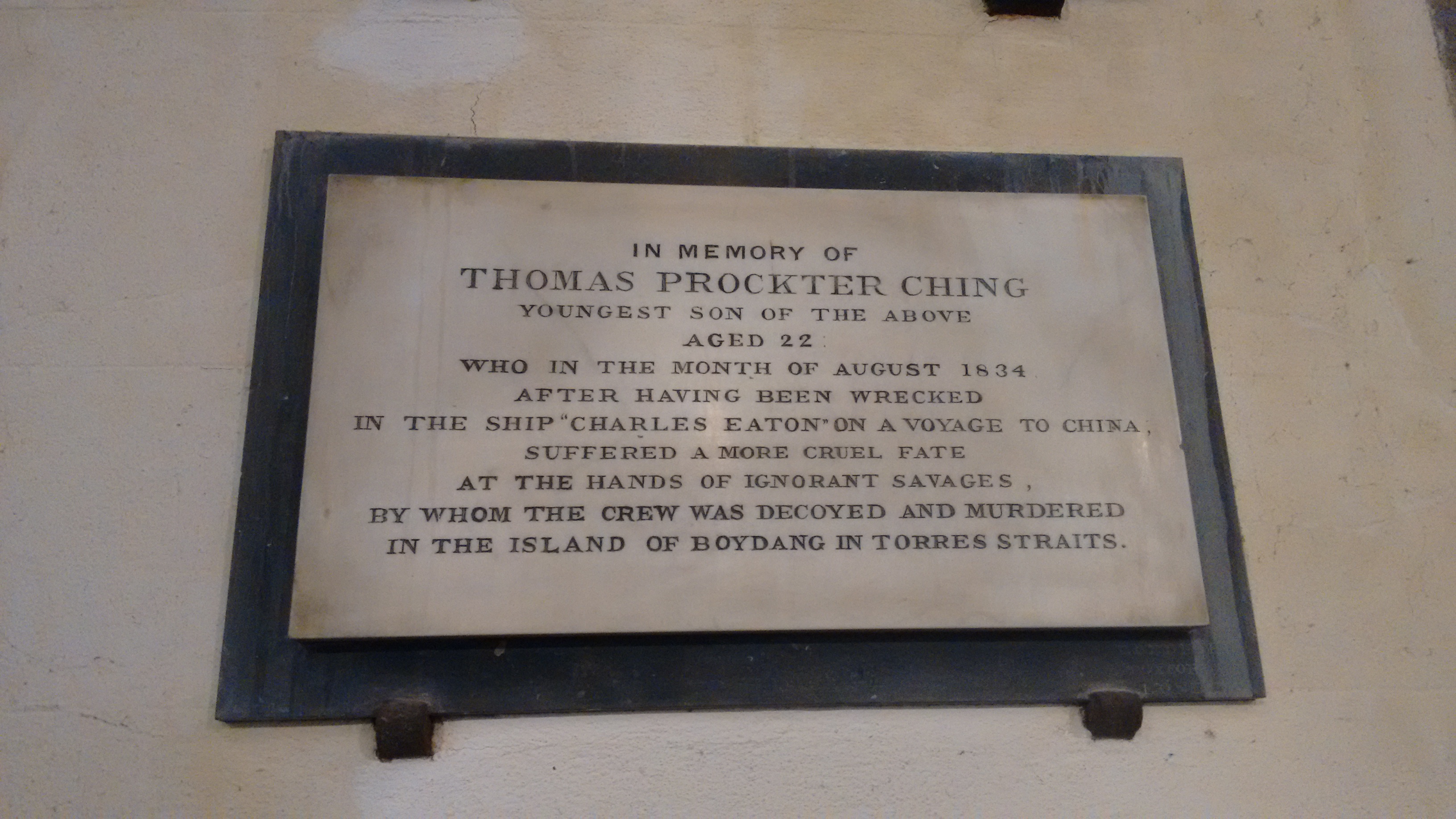

Back at to Launceston, John Ching, on hearing of his brothers fate had a commemoration plaque placed in St. Mary Magdalene Church in honour of Thomas. For years afterwards, oblivious possibly to the true meaning of their song, “Eton Eaton Eating Ching” was a song sang by many of the towns children.

A telling comment on the death of Thomas Ching appears on his parent’s monument just above his own. It read’s: “Watch and pray for ye know not when the time is.”

But for the natives among the islands of ‘Torres Straits’, in the long run, it is usually the Europeans who win and given added justification by such stories of inhumanity, a campaign of intermittent genocide was launched upon the Aborigines of the Torres Strait. The islands were claimed by Queensland and largely cleared of their native population. And so the sea lanes were cleared for the European cargo ships. On his return to England in 1837, John Ireland having worked his passage back, gave a disposition at a Court of Enquiry held in the Mansion House before the Alderman Pirie. After that he spent his life in quiet obscurity.

This is the full list of those that sailed aboard the ill fated ‘Charles Eaton’.

George Frederic MOORE, master C G ARMSTRONG, passenger F CLARE, chief mate Captain D’OYLY, passenger W MAYER, second mate Mrs D’OYLY, passenger- PYALL, THIRD MATE George D’OYLY, passenger G PIGOTT, bosun W T O D’OYLY, passenger J GRANT, surgeon one native Indian Mem servant L CONSTANTINE, carpenter W MONTGOMERY, steward W PERRY, midshipman Tommy CHING, midshipman S BAYLETT, seaman R QUIN, seaman A QUAIL, seaman W MOORE, seaman J CAEN, seaman Will HILL, seaman J BERRY, seaman G LOURNE, seaman W JEFFREY, seaman J WRIGHT, seaman W GUMBLE, seaman J MILLER, seaman W WILLIAMS, seaman C ROBINSON, seaman J PRICE, seaman J SEXTON, stewards boy J IRELAND, cabin boy.

Visits: 193