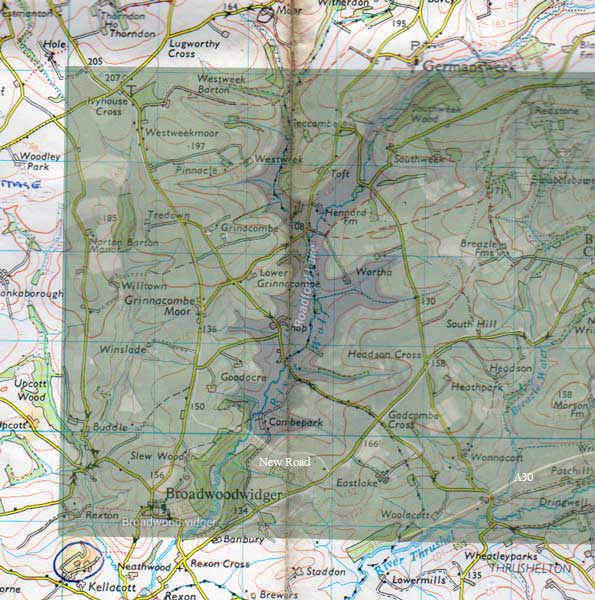

Roadford Lake is the centre-piece of a programme to almost double the region’s water storage capacity following the drought of 1976 which saw the last use of standpipes in the South West. The scheme was to impound the River Wolf (below) just to the north-east of Broadwoodwidger in West Devon, eight miles (13 km) east of Launceston and was selected as a site for the Reservoir in July 1975.

A public inquiry was held in March and April 1978, when local residents, the District Councils and the National Farmers’ Union were among the objectors. The inquiry was briefly re-opened in September of the same year to hear evidence about seismic activity, but the Inspector was subsequently satisfied that it posed no danger to Roadford. The story took another turn in April 1982 when a third reopening of the public inquiry was ordered – this time into the size of the reservoir. South West Water argued its case for the original proposal – a larger reservoir of 8,120 million gallons. After further delays Government approval was given in 1983 but for a smaller reservoir, only two-thirds the size of the original. However the drought of 1984 brought South West Water back to ask for the larger reservoir and dam, which was approved by the planning authorities in 1985. The area to be flooded took in the buildings and farms of Goatacre, Hennard Jefford, East and West Wortha, Pinch, and Shop Farm (below).

Above Mr. Moyse of Shop Farm in the 1930’s and a similar view of the farm in 1989

Shop had been farmed by several generation’s of the Moyse family (below), with George Moyse (seen sitting in the middle) being one of the last to farm the land in the Wolf valley. The family vacated the farm in 1984. The buildings were demolished after archaeological had completed. In the second picture Richard Yendell of Ashwater School seen interviewing George Moyse for Blue Peter in 1989.

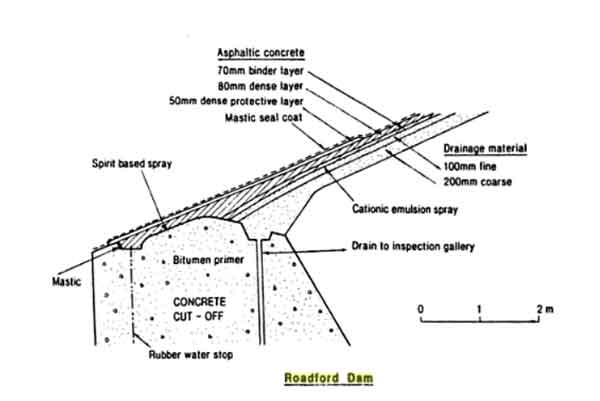

The access roads were the first part of the scheme, being started in January of 1985. Work on the damn, including the construction of hydroelectric generators to produce electricity, was begun in the spring of 1987 taking two years to complete with the impounding of the River Wolf starting in the autumn of 1989. The whole process was completed in 1990. The damn was constructed with asphaltic concrete membranes as the waterproofing element on the upstream face. The embankment is 40m high and 430m long, built of 1,000,00m3 of low grade rockfill which was quarried from the reservoir area upstream of the dam.

The creation of the reservoir permitted extensive archaeological research to be undertaken in the valley of the River Wolf led by Professor Mick Aston of Bristol University and documented by the Channel Four documentary series ‘Time Signs.’ Hennard Mill (below left), which in the 1980’s was an isolated farmstead, was found with documentary evidence to have

been a larger community just over a century previous, with a population of over 50 people.

Familiar local names such as Northey, Pengelly, and Smallacombe. As well as the farmers there were a potter, a miller and a Thomas Badcock who was a master shoemaker living with his wife, Ann, and their two children Catherine and William. Also living with them was his 74 year old mother-in-law Joanna Lucas listed as being a dependant. Over the next century the population began to move away and their homes and buildings began to fall into disrepair leaving by the time the archaeologist had arrived in 1989, nothing but a series of mounds and hollows. It is probably no coincidence that Hennard Mill’s depopulation began as the railways came to the area making travel far more accessible. That said however, in the 1861 census there is listed a John Hunkin manufacturer of bricks and tiles employing one person, a neighbour, Emanuel Avery, so people were adapting to the changing world and using the resources close to hand given that the area was made up of a heavy clay soil. (John Hunkin was born in Hatherleigh and his father, Samuel, was also a brick manufacturer, so John obviously moved to Hennard with the intention of setting up in the brick business).

Work was started on clearing the site, first with mechanical diggers to remove the sub-soil and vegetation. Then the painstaking and careful work of clearing the balance of debris took place to reveal the missing village of Hennard. The houses of the village were built on natural bedrock terraces surrounding a small green called ‘Town Place.’ This was crossed by distinct pathways with each building having just one downstairs room with a floor built of cobbles.

In some the buildings there were discovered a clear distinction of smooth cobbles and hearths for human habitation and rough cobbles with drains for livestock. The buildings were small and cramped where the people often shared the living space with their animals.

Along with the documentary evidence, the excavation soon discovered that Hennard Jefford was once a thriving hamlet with a heavy dependence on the cloth industry, milling its own corn and making its own clothes and shoes. The villages death followed along the lines of so many from that time with a gradual decline due to economic migration. (There are about 3,000 such villages/hamlets that have disappeared over time throughout the country)

During the excavation under the nineteenth century layer bits of medieval pottery were found which indicated the valley’s earlier life some 700 years prior to its flooding. Excavation of the mill pool uncovered the remains of an earlier mill wheel which were enough to be able to form an idea of how it looked in its entirety. Documentation from the seventeenth century showed that there was once a fulling mill (From the medieval period, the fulling of cloth often was undertaken in a water mill, known as a fulling mill, a walk mill, or a tuck mill) at Hennard mill and it also gave evidence to a medieval mill leat leading to the same site in the thirteenth century. This showed that a mill had been central to Hennard’s life for over 600 years. Further excavation on the site showed another mill further upstream which turned out to be the aforementioned fulling mill. This mill was thought to have been powered by an overshot waterwheel of about 9ft. In diameter.

Excavation commenced at Wortha (below) which reaped similar results as that at Hennard, of a small hamlet pre-dating the farmstead that then stood. Here evidence was found of a medieval village through bits of grain found at the site. The name ‘Wortha’ is derived from Anglo-Saxon and means enclosed homestead. Archaeologist’s found a ‘D’ shaped trench which showed a typical boundary created by farmers during the Saxon period over 1,000 years ago.

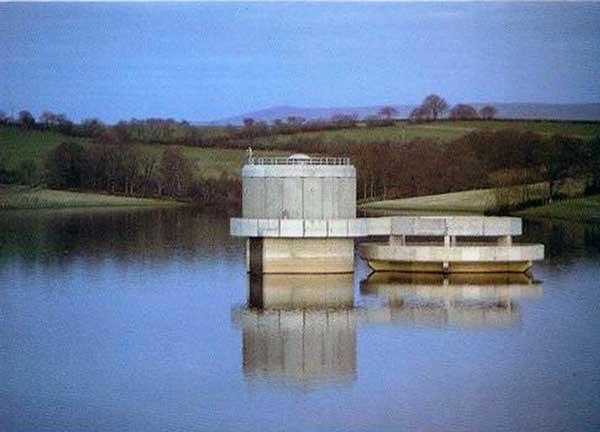

Roadford is now the largest area of fresh water in the southwest of England covering 730 acres of water (8,140 million gallons of Water). Operated by South West Water, it directly supplies water for North Devon. It also supplies Plymouth and South West Devon via releases into the River Tamar for abstraction at Gunnislake. It is also Local Nature Reserve and offers extensive leisure facilities such as watersports, trout angling, walks and cyclepaths.

Broadwood with Roadford Lake in the background. Copyright of Launceston Then.

Visits: 527