with thanks to Jim Edwards and Geoff Provis.

The First priory built at ‘Launceston’ was the Saxon one at St. Stephen’s, possibly somewhere across from the church. There was also a collegiate church and a Royal Mint, all built nearby. Circa 910 +.

Because the St. Stephen’s Priory was run as a cathedral and occupied by the same staff as a cathedral, it is stated that because William Warelwast, Bishop of Exeter under the Normans, did not fancy the trip into Cornwall, he requested that the old community be replaced by Augustinian friars. Jim Edwards, however, begs to differ with most history books. He points out that far from William Warelwast being responsible for the altering of the community and the re-siting of the priory, he points out that Leofric, who died in 1072, was the main cause of the change in the fraternity as he had bypassed the king and directly petitioned the Pope for the St Stephens canons to be replaced with Augustinian monks, and Warelwast, or Warlewast, was not a bishop until 1107, appointed by Henry 1, and died 1136. Osbern was bishop from 1072 died 1103; William Warelwast from 1107 to September 1137. William was succeeded by another Warelwast, Robert, from 1138 to 1155, who was, in turn, followed by Robert II from 1155 to 1160. Robert was succeeded by Bartholomew of Exeter, a local born boy.This was done, re-populating the priory with monks from Aldgate Priory in London, and around 1125 , a new priory was started around in the valley, beside the Kensey. This new priory was dedicated by Robert Warelwast on his triennial visit in 1150, and was opened on 7th February 1155 by one of the two Roberts. The new priory owned lands from the northern border of Cornwall all the way to Looe, and in Devon, becoming the richest priory in all Cornwall.

Now, back in 1140, William, Earl Warrenne, second son of Stephen of Blois, began an insurrection against the king, his father, and was joined by Reginald de Dunstanville, Earl of Cornwall, and his father-in-law William Fitz Richard (son of Ricardo Fitz Turoldi), who are said to have destroyed a church tower. (It is not known which one was responsible). Reginald and William were excommunicated and had to pay reparations to the priory and church.

It appears Reginald and others took to heart their lesson and many more lands were granted to the new priory as well as several charters giving the Prior many privileges and more power over local tithes and rents. “ The then Earl of Cornwall, who was a great benefactor to the collegiate church of St Stephen near Launceston, used his interest with King Stephen to bring back the bishopric to Cornwall, and fix the bishop’s see at St Stephen’s, in 1150. Robert Warlewast, Bishop of Exeter, opposed him, and in his first triennial visitation of his Cornish dioscese came and visited the collegiate church of St Stephen’s and suppressed the Order of secular priests and brought in, to supply their places, black monks and converted the church and college into the abbey, or priory, of St Stephen’s. The priory went from strength to strength, finally becoming the most powerful and richest in all Cornwall, and owning a great deal of property in Devon, as well. It is said that every parish from Kilkhampton to Looe paid rent to the Priory, and some in Devon.

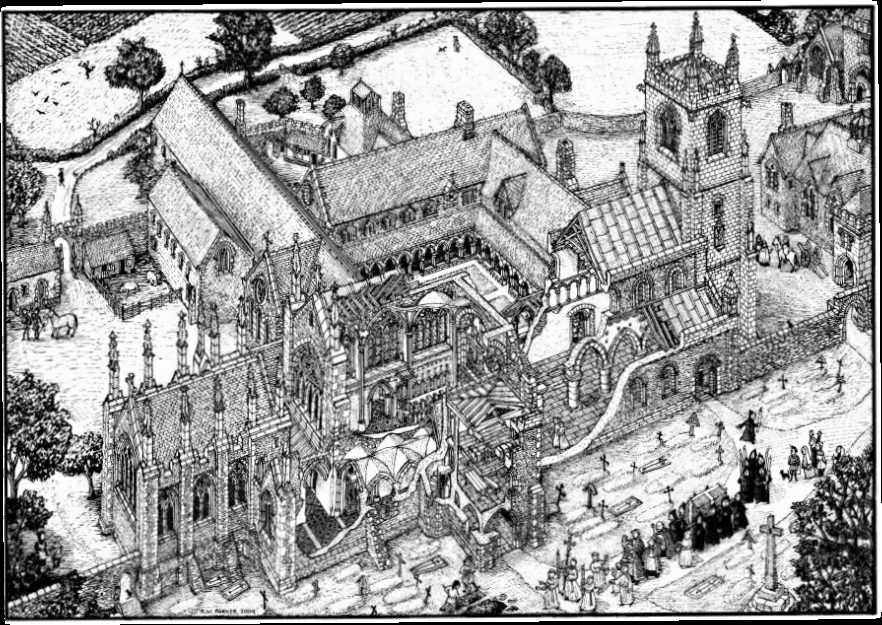

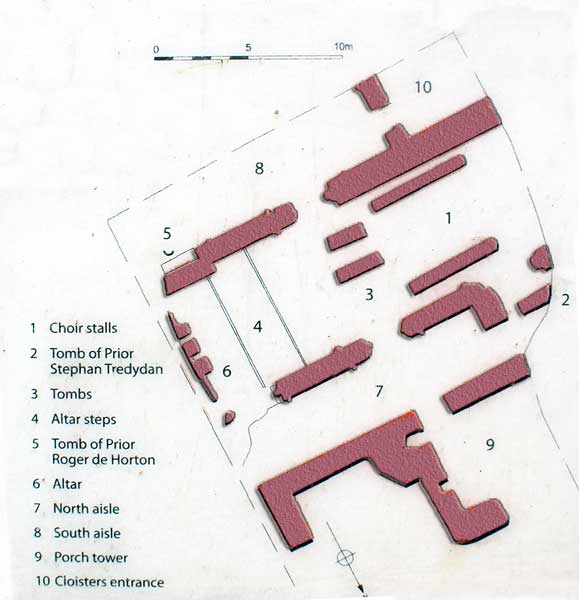

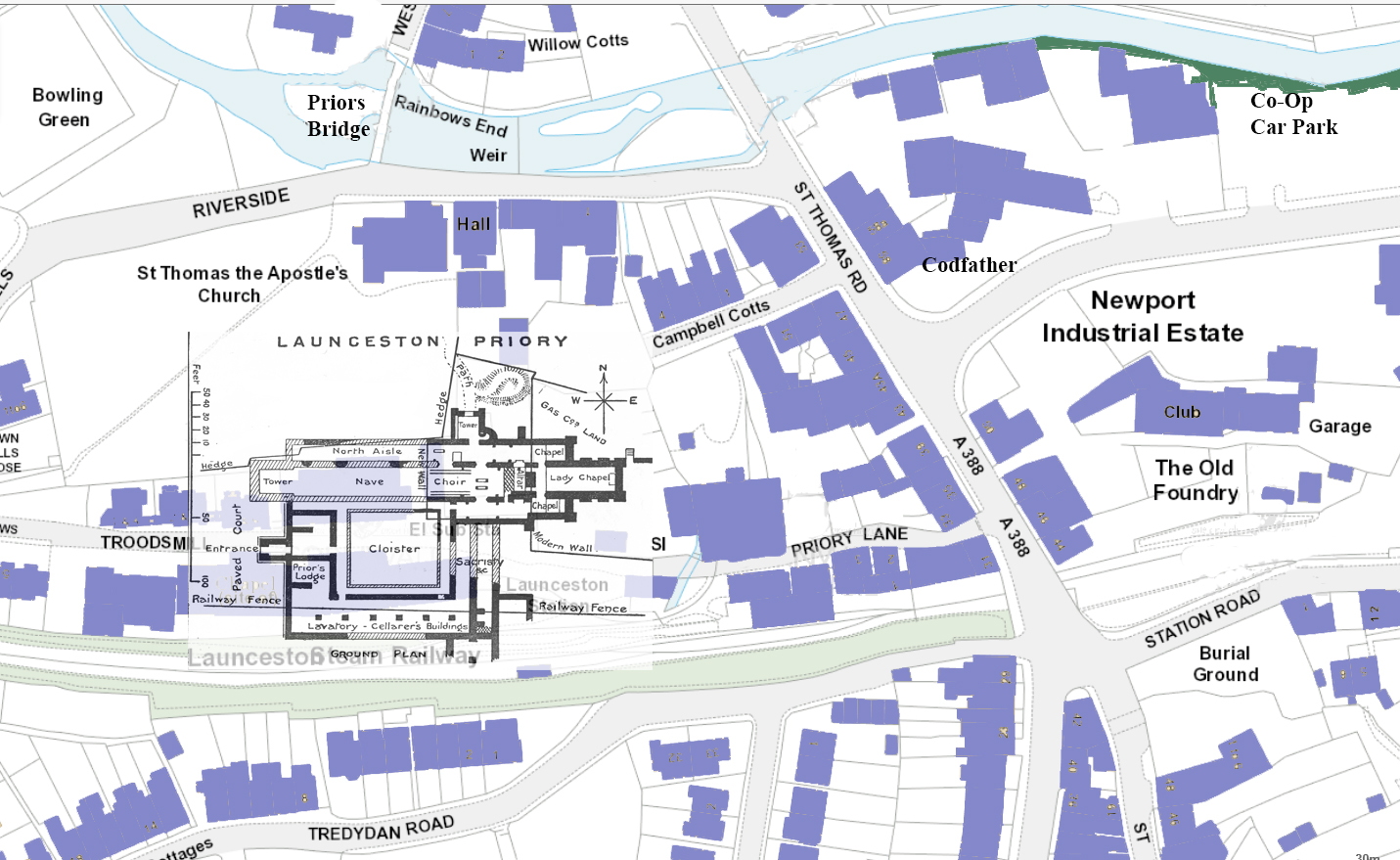

The new priory consisted of a conventional church, refectory, dormitory and chantry chapels with dedications to St Margaret, St James, St Gabriel, St Thomas, St Catherine, and, later, St John of Bridlington.

The first priory was open for about 220 years, the second, from 7 February, 1155 to 24 Feb 1539, 354 years. A grand total of priory rule of 574 years.

About 122 Mayors of Launceston must have seen the priory in all its glory, and would have dealt with the prior and his fraternity.

______________________________________________________

The Daily Life of Medieval Monks

The daily life of Medieval monks in the Middle Ages were based on the three main vows:

The Vow of Poverty

The Vow of Chastity

The Vow of Obedience

Medieval Monks chose to renounce all worldly life and goods and spend their lives working under the strict routine and discipline of life in a Medieval Monastery. The reasons for becoming a monk, their clothes and the different orders are detailed in Medieval Monks. This section specifically applies to the daily life of the monks.

The Daily Life of Medieval MonksThe daily life of Medieval monks was dedicated to worship, reading, and manual labor. In addition to their attendance at church, the monks spent several hours in reading from the Bible, private prayer, and meditation. During the day the Medieval monks worked hard in the Monastery and on its lands. The life of medieval monks were filled with the following work and chores:

Washing and cooking for the monastery

Raising the necessary supplies of vegetables and grain

Reaping, Sowing, Ploughing, Binding and Thatching, Haymaking and Threshing

Producing wine, ale and honey

Providing medical care for the community

Providing education for boys and novices

Copying the manuscripts of classical authors

Providing hospitality for pilgrims

The Daily Life of Medieval Monks – Monastic Jobs and OccupationsThe daily life of Medieval monks included many different jobs and occupations. The names and descriptions of many of these positions are detailed below:

Abbot – the head of an abbey

Almoner – an almoner was an officer of a monastery who dispensed alms to the poor and sick

Barber Surgeon – the monk who shaved the faces and tonsures of the monks and performed light surgery

Cantor – the cantor was the monk whose liturgical function is to lead the choir

Cellarer – the cellarer was the monk who supervised the general provisioning of the monastery

Infirmarian – the monk in charge of the infirmary

Lector – a lector was a monk entrusted with reading the lessons in church or in the refectory.

Sacrist – the sacrist was the monk responsible for the safekeeping of books, vestments and vessels, and for the maintenance of the monastery’s buildings

Prior – in an abbey the deputy of the abbot or the superior of a monastery that did not have the status of an abbey

Daily Life of a Monk in the Middle Ages – the Daily RoutineThe daily life of a Medieval monk during the Middle Ages centred around the hours. The Book of Hours was the main prayer book and was divided into eight sections, or hours, that were meant to be read at specific times of the day. Each section contained prayers, psalms, hymns, and other readings intended to help the monks secure salvation for himself. Each day was divided into these eight sacred offices, beginning and ending with prayer services in the monastery church. These were the times specified for the recitation of divine office which was the term used to describe the cycle of daily devotions. The times of these prayers were called by the following names – Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, Nones, Vespers and Compline:

Lauds : the early morning service of divine office approx 5am

Matins : the night office; the service recited at 2 am in the divine office

Prime : The 6am service

Sext : the third of the Little Hours of divine office, recited at the sixth hour (noon)

Nones : the fourth of the Little Hours of the divine office, recited at the ninth hour (3 pm)

Terce : the second of the Little Hours of divine office, recited at the third hour (9 am)

Vespers : the evening service of divine office, recited before dark (4 – 5pm)

Compline : the last of the day services of divine office, recited before retiring (6pm)

Any work was immediately ceased at these times of daily prayer. The monks were required to stop what they were doing and attend the services. The food of the monks was generally basic and the mainstay of which was bread and meat. The beds they slept on were pallets filled with straw.

___________________________________________________________________

The Cartulary of the Priory, or the Priory Records, copies of which are held in the local library, make very interesting reading for anyone interested in history, detailing many deeds and gifts, and law suits regarding the rights and uses of the rights, of the tithes and the rents and gifts of land and property until it was surrendered in 1539. In 1539, under Henry VIII. it suffered the same fate as all the other priories and was closed on 24th. February, 1539, by a Cornishman, John Tregonnell. By this time the Priory had grown to be the wealthiest and largest religious hose in Cornwall wit a net income of £354 per year and owning 250 lands around Launceston and to distant parishes such as Kilkhampton, St. Gennys, Stoke Climsland, Looe Island, Pyworthy and Bradford.

The site, and much more, was handed, in fee, to Gawen Carew (later knighted) in March, 1540, who destroyed the church and used some of the buildings as stables, bakeries and pigsties, and selling off the fabric to build houses in the locality. The site was later sold to Richard Connocke, son of a Liskeard solicitor, who next sold it to Sir Francis Drake, Bart., of Buckland Monachorum, (nephew of the sailor).

The Priory served as a point for acquiring building materials and much of the building was dismantled and carried away until there was very little left. It was often said that of all the stone pilfered from the priory were suddenly to be returned, half the town would fall down!

Time gradually buried the site until the 19th century when all traces of the building had totally disappeared under 10 to 12 feet of soil. Then in 1886 with the construction of a new siding into the Troods buildings, parts of the site were uncovered, this was followed in 1888 when the construction of a new Gas holder uncovered further parts of the building.

Post & News, 1st September 1906. Old Priory Skeletons. Launceston, August 25th.

Whilst excavating at the old Launceston Gas Works Company’s gas works on Tuesday for the purpose of providing a pit for the spent liquor from the manufacture of sulphate of ammonia, William Hoskins and William Gimblett unearthed two human skeletons. The grave was about six feet deep. Many parts of the bodies, which were laid side by side, were quite discernable, and the teeth which the workmen extracted were like ivory. On account of the decomposition of the bodies, the ground underneath was quite black, and underneath this again was a layer of clay which showed signs of wonderful durability.

When first discovered the skeletons were intact but on removal the various positions became disarranged , and it was in this state that our representative saw them. The jaw bones and the bones of the knee and hips were plainly to be seen, and the skulls were about a quarter of an inch thick. Comments by Mr Otho B. Peter:- Mr O. B. Peter, the greatest living authority on all that pertains to the ruins of the old Priory of Launceston, ahs favoured us with the following interesting comments on the human skeletons unearthed at the Launceston gas works on August 21st, an account of which appeared exclusively in our Thursday edition last week.

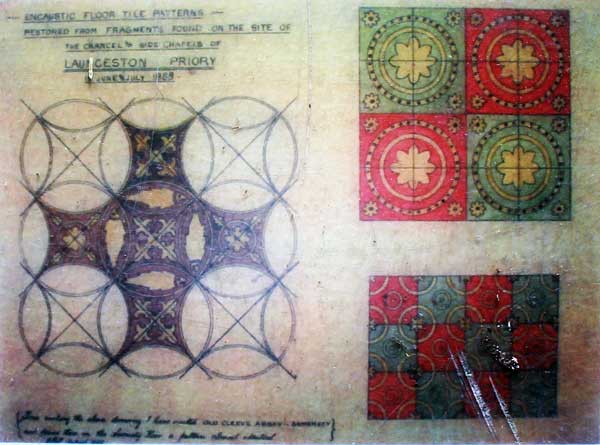

“In August 1888, when the deep excavation was made to receive the gasometer which is nearest the preserved portion of the Priory site, the whole of the foundation of the chancel of this church, with its two side chapels were uncovered and destroyed.

On behalf of the Launceston Scientific and Historical Society, I was allowed to take measurements and make drawings of the relics found. These included numerous graves, both outside and inside the old wall (see my illustrated book on Launceston Priory, published January 1889). The skeletons unearthed last week were in that portion of the Priory churchyard which was just outside the south wall of the chancel. The remains lay seven feet below the present surface of the ground, in a horizontal position, with the feet towards the east, and rested on a bed of clay. A few rough stones set vertically, formed the sides and feet of the graves, and stones, laid flat, were under the skulls. No coffins were used, not were there any covering stones. This was one of the most primitive modes of burial known to archaeologists and tallies with other graves found in 1888. The bones disturbed will be interred in the churchyard of St Thomas adjoining the site.

It was in 1888 that Mr. Otho Bathurst Peter became involved and through his encouragement, excavations took place to re-discover the site. This is what Otho had to say in 1909:

“Some years ago while reading certain ancient writings I noticed several references to a large monastic establishment which was described as having existed on the eastern boundary of the parish of St. Thomas-the Apostle, next Launceston. As after diligent inquiries I could gain no assistance from the folks of the neighbourhood in regard to any traditional site of this building, I determined to personally explore the district, and aided by notes from the above mentioned writings, and by excavations that happened to be making at the time for a local railway cutting, the foundations of its walls were eventually discovered some eight or twelve feet below the surface of the ground. I then managed to so arouse the curiosity of the public by suggestions as to what might be under the sod that the owners of the land willingly gave me permission to dig, and other people liberally subscribed towards the cost of excavating and removing the top soil. I was this enabled to uncover and trace out the lines of what must once have been a magnificent square planned group of buildings standing on a level plot of ground and measuring about 230 feet in length and in width”.

Unfortunately the site was left again and over the coming years fell into disrepair once more, however, in 1976 the ruins were tidied up by members of St. Thomas Youth Club and shorthly afterwards a service, the first for over 400 years, was held on the site. In 2001 the first candlemas service was held for almost 500 years, and was attended by over 200 people.

In 2008 a more extensive clean up was performed, with important conservation work undertaken by North Cornwall District Council, the Environment Service, local volunteers and other organisations funded by a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

With the site now consolidated, it is now cared for by the Friends of Launceston Priory in partnership with Launceston Town Council.

Above 13th-14th Century Floor Tile found at Launceston Priory.

Launceston Priory Gallery

Visits: 244