.

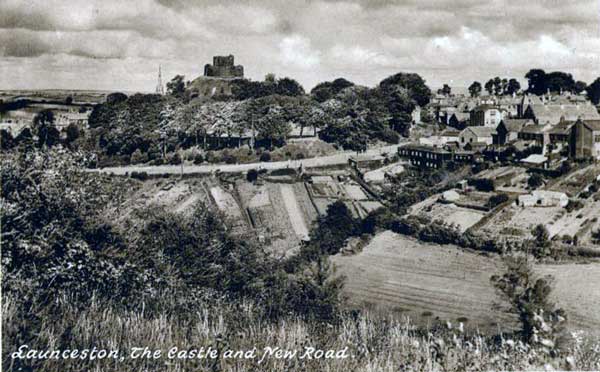

Until 1834 the only way into Launceston from the north was the very steep hill with gradient 1 in 5 1/2, from Newport to North Gate, and thence straight up the further hill or by way of Tower Street, then called Back Lane. The North Gate was smaller than the South Gate, and, following complaints from farmers about the difficulty of getting carts through it, it was demolished in 1832. This is the date given by Peter in his ‘Histories of Launceston and Dunheved’ and the one which is generally accepted, though Robbins says it was 1834. The removal of this ancient monument made the entrance to the town somewhat wider, but did not alter the inclination. It was decided therefore, to build an entirely new road with a more gradual slope, nowhere exceeding 1 in 11, on the other side of the castle. This was not opened for traffic until 1834, but preliminary matters were being discussed in 1831 and negotiations were proceeding during the following months.

The land through which the road was to run was largely the property of the Duchy of Cornwall, which had the reverted to the King owing to the lack of a Duke. It was suggested that perhaps a gift of the freehold of the land might be made for such a public purpose. The first communication with the Duchy Office took place when Thomas Pearse, a Launceton attorney, called on Abbott one of the officials, at Somerset House and made the request in person in January, 1832. Abbott replied that they would need a “Plan and Specification of the present and intended New Lines, and said the Duchy could not give the ground without and Act of Parliament.” On Pearse’s return to Launceston, the required documents were sent on by Charles Gurney. Nothing happened for a few weeks, and then Sir William Molesworth, who had originally proposed that subscriptions should be collected to defray the cost of the work, thought that a decision might be hastened if he could use some of his influence in the right quarter. So he wrote to Edward William Pendarves, who was one of the two mMembers for the County, and asked him to see Sir George Harrison, the Duchy Auditor. This interview resulted in a survey of the ground by Brent, the Surveyor-General of the Duchy, who sent his report to the Duchy Council early in July. In it he stated that the value of the land was £227 16s. 3d. of which £34 7s. 6d. was due to the Duchy and £143 8s. 9d. to the leesee. On July 5, Harrison wrote to Pendarves to this effect and added that “I have no doubt that the consent of the Crown will very shortly be given to the measure.” On July 13, Sir Henry Hardinge took up the question with Harrison. Nine days later the Duchy Auditor wrote to Pendarves as follows:

“With reference to my letter to you communicating the purport of our Surveyor-General’s Report on the subject of the land required for the New Road near Launceston, in which I informed you that, with a view to the legal interest of his successors, His Majesty would be bound to receive the sum of £84 7s. 6d. (being the share of the King in right of His Majesty’s Duchy) and to invest it in the three per cent Consols, I have now the pleasing task of informing you (which I am enabled to do by a letter I have received from Sir Herbert Taylor) that, with that gracious consideration which the King has ever evinced, to extend his royal beneficence towards those objects which may so materially benefit His Majesty’s good subjects in Cornwall, and so essentially contribute to their comfort, as the completion of this New Line of Road near Launceston, it is His Majesty’s intention to grant of His Majesty’s Duchy Revenues a present donation of £200 and, if it should be required, His Majesty will next year be pleased to grant a further donation of £100 towards this object.” Sir Henry Hardinge, Launceston’s M.P., also received a letter on the same lines.

A public meeting was held in the borough on Monday, July 30, at which it was agreed to ask the Secretary of State to present an address of thanks to the King for his donation. This was forwarded through the Mayor, Parr Cunningham Hockin, who received the following reply from Whitehall, dated August 4: “The Mayor of Launceston. Sir, I am directed by Viscount Melbourne to inform you that he has not failed to lay before the King the address from the inhabitants of Launceston, expressing their grateful sense of his Royal Munificence in having subscribed £200 towards the improvement of the road from Newport to Launceston, and that His Majesty was pleased to receive this address very graciously. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your Obedient Servant, S. M. Phillipps.”

The facts above are undisputed, but the usual vituperative wrangle arose at the meeting when the question was raised whether Pendarves or Hardinge had brought the greater influence to bear to obtain the King’s gift. This quarrel continued for weeks; it assumed county proportions and was the subject of correspondence in ‘The West Briton’ from August 3 onwards. A long letter from Thomas Pearse, which appeared in that paper in the issue dated August 24. The details of this wrangle are not of interest today, but, when the bitterness had died down and the construction had been completed, the King’s generosity was acknowledged by calling the road from the present Guildhall Square to the present National School ‘King William Street,’ and is so named on old maps (below in an 1842 map of the town). To this day many still know it as ‘New Road,’ although it now forms part of and is know as St. Thomas Road.

Visits: 112