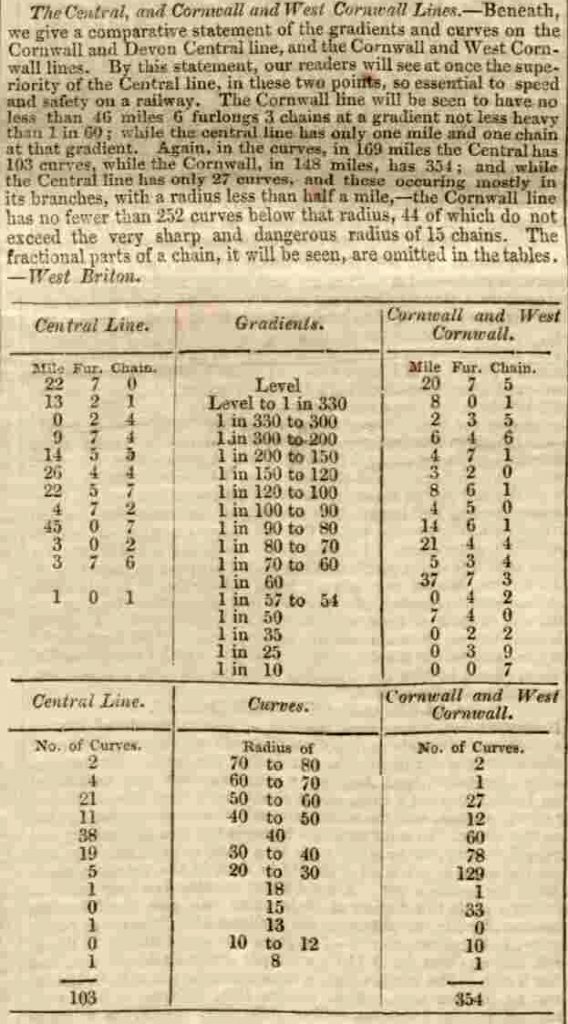

.

For centuries passage over Bodmin Moor was extremely difficult with nothing more than just a basic packhorse track dating from the time of the Normans. It wasn’t until the late 18th century that a turnpike road of any extent was cut across the barren land that lay between Launceston and Bodmin. It is with this knowledge that we bare witness to the imagination, dreams and sometimes outright absurdity of the Victorian railway pioneers and their plans to tame the moors for a railway line to cut across the bogs and granite strewn plains. Many schemes were thought of, from the ‘Railway Madness’ of the 1840’s, to more watered down schemes later in the century. One can only wonder just how the railway network would have survived in Cornwall had any of the projected schemes have been built. A central line would certainly have been helpful when the climate challenges the only line now coming out of Cornwall, at Dawlish seafront. But as it turned out, Dr. Beecham didn’t have any of this to consider as none of the schemes were successful, and today we are left with no railway in the North-East of Cornwall. Here we look at some of those failed central Cornwall schemes.

The first scheme.

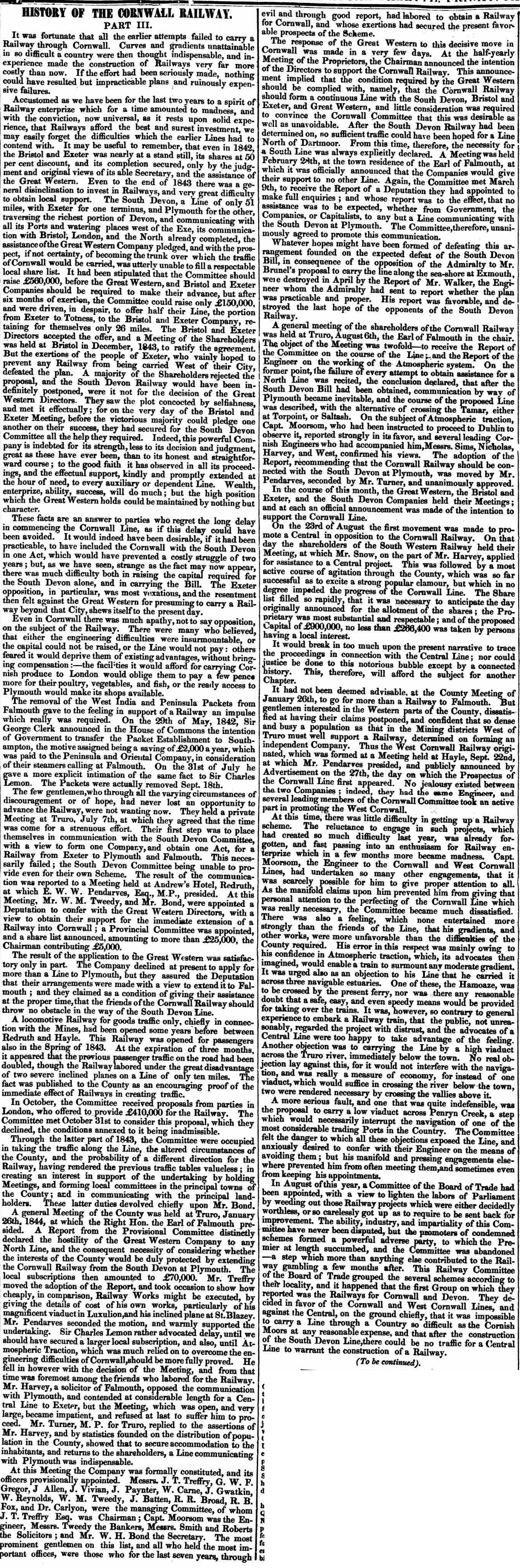

It was the construction of the London to Southampton railway in 1840 that had attracted the attention that had spurred on the Central Cornwall railway proposal with many especially in Falmouth becoming very concerned to losing the packet trade to the south coast town. Falmouth had for many years had nearly all of the packet trade: dispatches from the Colonies and overseas territories arrived by ship and were conveyed to London by road coach. The primitive roads of those days made this a slow business and Southampton was developing in importance. The completion of the London and Southampton Railway meant that dispatches could be taken on to London swiftly by train and those original fears inevitably proved correct when the Government removed the bulk of the packet traffic to Southampton by 1850.

Although as early as 1838 a scheme to build a railway from Falmouth to London via Exeter had been proposed this had been fixed upon a coastal route. The Cornwall central line proposal was an idea that had been formulating for some time but a series of meetings throughout the Cornwall led to the first publicised mention coming in August 1844 when Falmouth solicitor Mr. Harvey, attended the half-yearly meeting of the London and Southampton Railway. His attendance was in the capacity of solicitor to the projected Cornwall central line and he addressed the meeting as so; “There was one point to which he wished to draw the attention of the meeting for a moment. The portion of the report to which he alluded was, where mention was made of a line in the direction of Shaftesbury, Sherborne and Yeovil, to the Great Western line at Taunton or Exeter. He did not wish to influence the Directors or Proprietors in that which they now had in hand, but he felt incumbent that he should, as a west of England man, and well acquainted with that part of the country, and the state of feeling existing there in reference to railway extension, that he should put the Proprietors in possession of his sentiments on the subject, and give some reasons for going with the line, not to Taunton, but to Exeter. If there was one mistake more than another, which the Great Western Company had committed, it was in reference to the South Devon line, in making the line by the coast instead of a central one. It should be recollected that Devonshire extended about 75 miles across from one side to the other. Such a line therefore could be of no use to the inhabitants of the northern districts of the county. In fact, with exception of the inhabitants of Plymouth, Devonport and other places situated near the coast, the people of Cornwall were very desirous that a central line should be made, but the people both of Cornwall and Devon waited till a line was carried down to Exeter. Independent pf all this popular feeling in favor of a line, we were sure that Government would be delighted with such a project. They had Capt. Moorsom’s estimate, since which the line was surveyed by Capt. Thomas, and the returns were calculated at from 7 to 7 1/2 per cent. His (Mr. Snow’s) object now was to show not only the possibility but the expediency of extended the Salisbury line to Exeter. Such an extension would occasion a saving of at least 24 miles over the route by Bristol to Exeter. Various meetings had recently been held in towns situated in the part of the country to which he alluded; all of which had declared strongly in favor of this line!!! A gentleman from Falmouth, Mr. Harvey, solicitor for this projected central line, was now present, and was fully prepared to give the meeting every information on the subject. The whole line from Exeter to Falmouth, he (Mr. Snow) was of opinion would cost less than one from Exeter to Plymouth.”

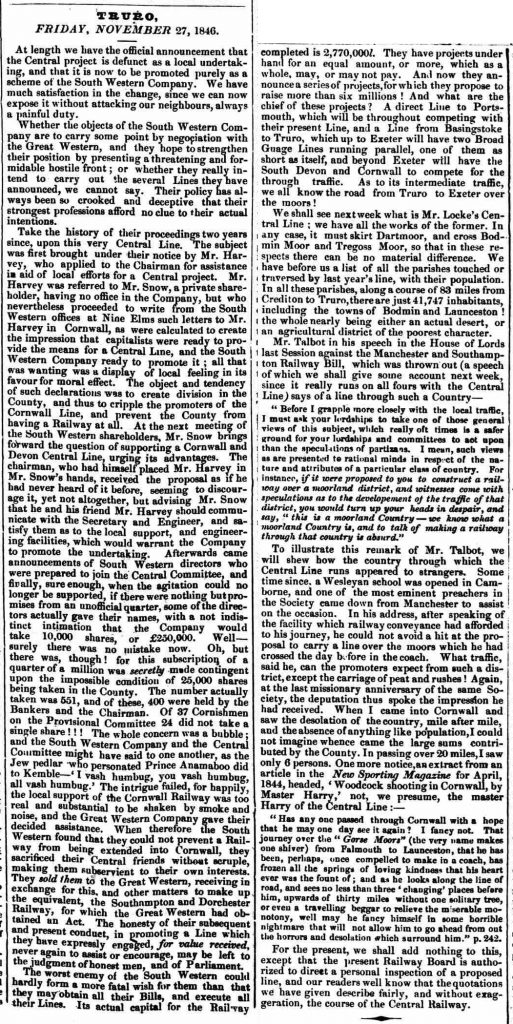

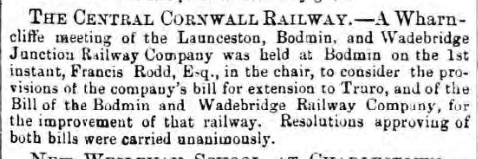

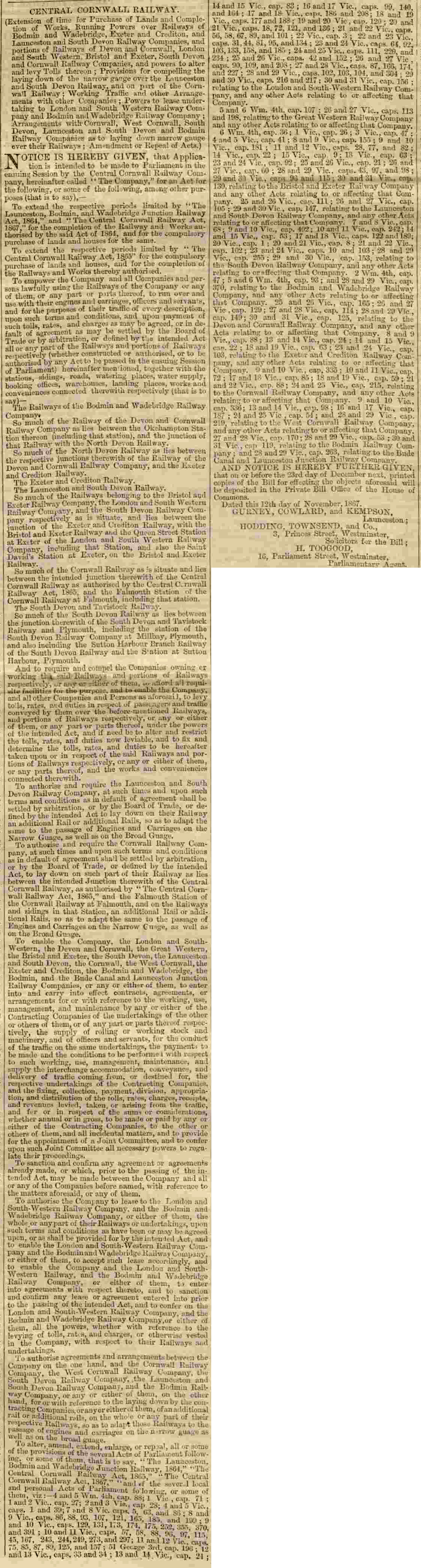

The Chairman replied that he was gratified with the statement of Mr. Harvey, but he did not see “how they could grapple with the subject at present.” He thought the best plan would be to communicate with Mr. Locke on the subject, and in conjunction write to the Secretary, showing what probability there was of raising the requisite capital. The following month further meetings (below left and right) were held with positive results.

The biggest problem to the scheme would be the rivalry between the two major railway companies in the area, the GWR and LSWR. The former had brought its broad gauge line as far as Plymouth by 1848 thus meaning their interest would lie solely along the coastal route. The Central line protagonists would use the difficulty of crossing the Hamoaze as one reason for their route, even though Brunel himself had stated as early as 1844 that he saw no difficulty in bridging the crossing. Another reason in support for the coastal option was the connection of Cornwall with Plymouth and Exeter giving the population strength advantage of 46,000 over the central line option although this was countered with the claim that the central line was of less mileage. Further problems for the central line came from the perceived reluctance of some members of the LSWR to place their names in support of the central scheme.

With strong arguments from both sets of proponents it fell to the Board of Trade to decide which scheme it would allow and in early January 1845 it gave its decision coming down on the side of the coastal route laying down in its argument that ‘central line left the coast defenceless, so that an enemy might at any time have landed and ravaged our territory with impunity.’ The Duke of Wellington himself had addressed the Board in regard to the military need not to extend coast lines further than ten miles inland. The Board also sighted the fact that permission had already been granted for the South Devon line from Exeter to Plymouth, by which a large proportion of the central lines envisaged traffic would actually travel. This agreed line would entail just another 66 miles of new railway as compared to one 100 1/2 by the central line. The report also brought into question the cost to construct the central line stating that ‘Throughout the whole length it has hardly a mile running at or near the natural surface of the ground. It has nine tunnels whose united lengths amounts to 4,820 yards, eight miles of cutting at depths exceeding 50 feet; nine miles of embankment of height exceeding 70 feet, and 1,076 yards of viaduct, at heights of 83 and 45 feet.’ The report went on; ‘The difficulty and expense of such immense works are greatly enhanced by the geological character of the district through which they would have to be constructed. It appears from statements submitted to us (the Board of Trade), that one tunnel of 700 yards, at a depth of 146 feet below the surface, is through granite; a cutting of 1 3/4 mile, as deep in parts as 70 feet, is through granite and hard greenstone; and, generally speaking, a great part of the line runs through granite, greenstone, silicious slate, and other rocks of a hard description.’ ‘The general experience of railway construction’ the report continued ‘the gradients of the proposed central line are very severe. At the Falmouth end there is a gradient of two miles ten chains in length, at an inclination of 1 in 60, terminating in a curve of twenty chains radius. In the central portion of the line there is a continued ascent to the summit on one side of eleven miles, at an average inclination of 1 in 92; and on the other side, of ten miles, at an average inclination of nearly 1 in 100.‘ The conclusion of the Board was that there was considerable doubt that the works would come in on budget; ‘Considering, therefore, the unusually expensive nature of the works upon the central line, the severity of its gradients, implying additional cost in working, and the comparatively small amount of traffic that could be expected to pass over it, we have had no hesitation in arriving at the opinion that it must be considered, under present circumstances, as altogether impracticable as a commercial undertaking.’ The Board of Trade had taken into consideration another central line proposal that had not gained much support called the Great Western and Cornwall Junction, the plans of which has been deposited with the department. The report stated ‘we have thought it right to investigate its engineering circumstances, in order to ascertain whether there was any probability of an easier line that that of the Cornwall and Devon Central being found in a different direction. The result of this investigation has been, however, to satisfy us that the project in question was even more objectionable that that already described. Although the plans and sections deposited with us are in such an imperfect stated that the necessary information is not always to be obtained, the extreme height and depth of the embankments and cuttings being, for instance, frequently omitted, enough appears upon them to show that the line is one continued succession of cuttings and embankments, many of which are enormous dimensions. There are 31 cuttings, whose depths exceeds 50 feet, some of them reaching the depth of 90 and 100 feet; 11 embankments exceeding 70 feet in height; 4,380 yards of tunnels, and 9 viaducts, of the length of 3,980 yards.’ The Board of Trade report concluded we, therefore; ‘are compelled to abandon the idea of a central line as altogether impracticable, and to continue ourselves to the sole question of the coast line from Plymouth to Falmouth. This line is only 66 miles in length, and the works are not on the whole, of a very heavy character. On the whole, the Board are of the opinion that the coastal line from Plymouth to Falmouth is a good commercial speculation, and the only practicable railway communication between Devon and Cornwall. The passage of the Hamoaze no very important objection; the proposed crossing is sheltered from the sea; and the Torpoint Steam Ferry has crossed near the same spot every quarter of an hour for ten years, without interruption, and getting over in six or seven minutes.’ And with that they agreed to allow the passing of the coastal line scheme.

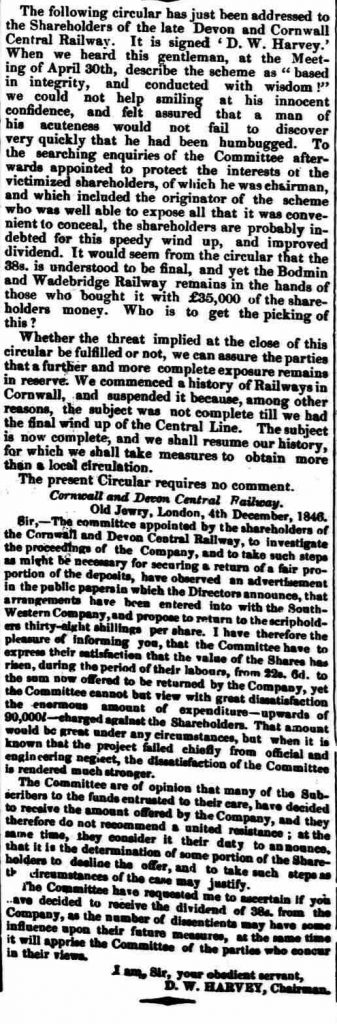

The Cornwall and Devon Central Railway shareholders met at the end of April and after agreeing to exchange shares in the Coastal Line Company for dropping their opposition to the coastal scheme, the company was liquidated. This though didn’t stop the clamour for a central line through the county, and after the coastal line received a ‘postponement’ in the House of Lords, a meeting was convened at Bodmin in August 1845, to support another attempt at pursuing a central line. This was attended by most of the landed gentry, and tradespeople of the county, including the High Sheriff of Cornwall, Francis Rodd of Trebartha.

The second scheme.

Faced with renewed opposition as the above and preceeding article show, in November 1845, the Cornwall Central Line board agreed to amalgamate with the ‘Salisbury and Yeovil’ and ‘Dorchester and Southampton’ companies respectively. By now there were two schemes vying against each other with the new ‘Central Line’ proposed to take a route skirting around the north of Bodmin Moor from Bodmin to Camelford before passing Roughtor and then taking a southerly passage to Launceston before heading to Exeter via Hatherleigh and Crediton. The new ‘southerly route’ was to follow a line from Truro to St. Austell before travelling to Lostwithiel and up the Fowey Valley to Bodmin. From here the line was to continue to follow the Fowey River till about three miles west of Liskeard, it was to run north east to Launceston before it too would head towards Hatherleigh, Crediton and Exeter.

This second scheme however, fell at its first hurdle, when at the Committee of Standing Orders in the House of Lords, the reading of the Bill was halted part of the way through when it became very apparent that serious errors had been made in the plans. The alternative coastal plan did make its way through the House of Lords but itself went no further.

Third scheme (an alternative).

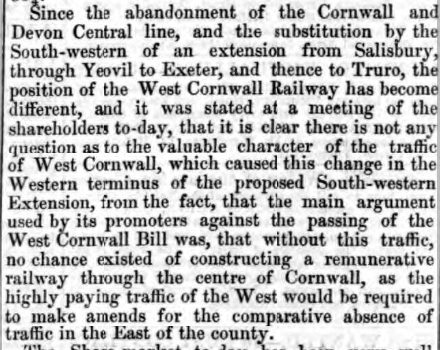

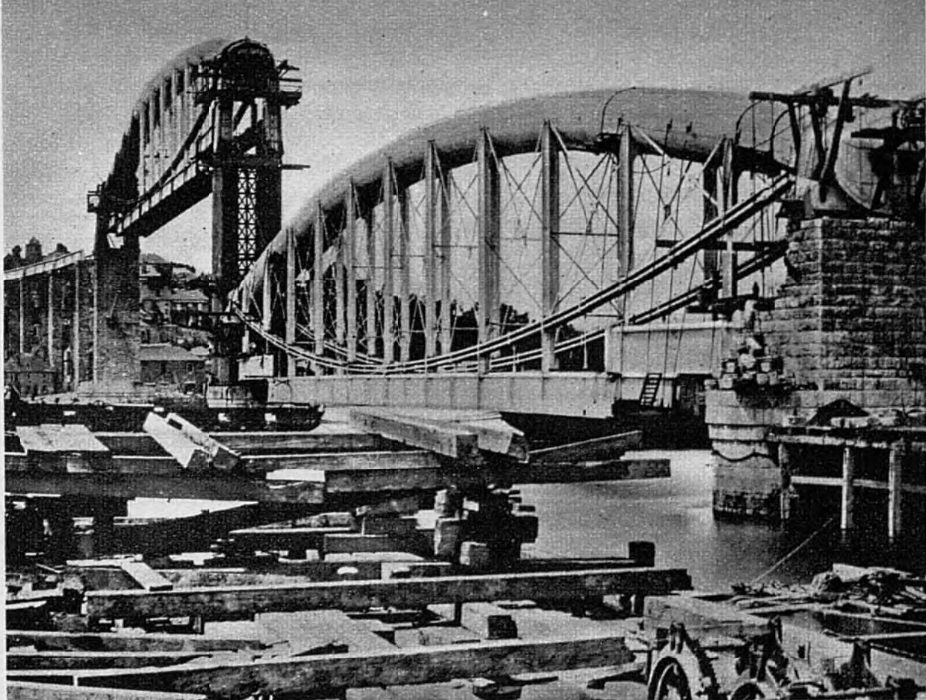

Over the following years various mentions were made of a central scheme, but more in the hope of connecting Launceston and North Devon to the national railway network using part of the earlier abandoned proposals. Although a meeting was held by group from around the Launceston area in December 1852 (above) to discuss a wider central rail scheme connecting with the West of Cornwall, this came to nothing, not even a line from Plymouth to Launceston, which would take another thirteen years to bring to fruition. It would be another nine years before the subject of a central line would again be discussed, however, by this time the coastal line had been constructed with the Truro to Penzance being opened in 1852 and after an Act of August 3rd, 1846, the Truro to Plymouth in 1859 with the problematic crossing of the Tamar being made with Brunel’s iconic ‘Royal Albert Bridge’ (below). Surveys of the site were begun in 1848, but it would be another 6 years before construction took place, which in turn took another 5 years to complete with the bridge being opened by Prince Albert on May 2nd, 1859.

In 1861 an attempt was made on another central line scheme but this soon fell and it wasn’t until late 1863, just as the construction of the Launceston and South Devon Railway from Tavistock had begun, that meetings were held to discuss an extension of this line being onwards to Bodmin. This, the ‘Launceston, Bodmin and Wadebridge Railway Junction’, was proposed to follow the Kensey valley for 4 to 5 miles and then through a short tunnel to Pipers Pool then to pass North of Brown Willey to Camelford. From here it was proposed to follow the Camel valley to Wenford Bridge where it would join the Northern part of the ‘Bodmin and Wadebridge Railway’. It was the suggested that an 8 mile extension from Ruthern Bridge to Burngallow could be added, thus connecting the main coastal line to Truro and Falmouth.

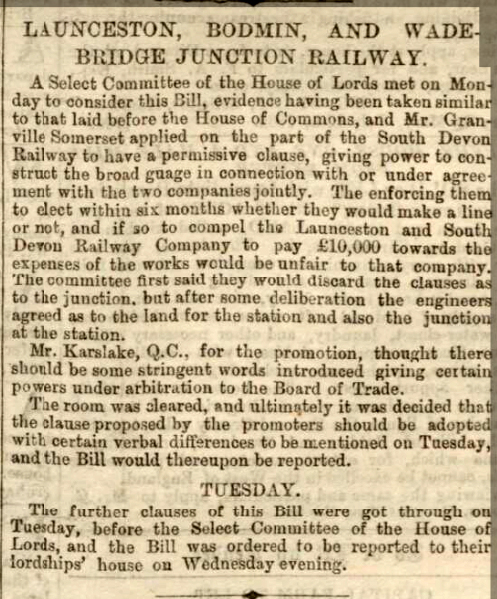

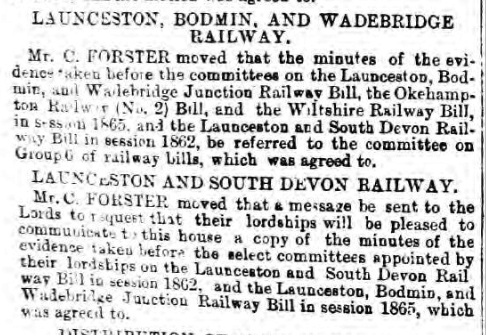

By the beginning of the following year the scheme passed standing orders on its way to an Act of Parliament and on the 16th February, 1864, it had its second reading. However, the fledgling committee face stern opposition not least than from Launceston and South Devon Railway who argued against the line being narrow gauged compared to their prospective line into Launceston being broad gauge.

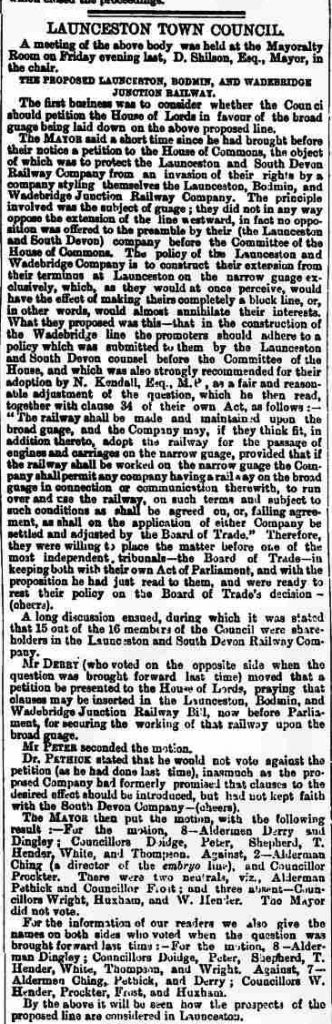

With increasing support from the respective town councils from Bodmin and St. Columb, the bill passed through committee on April 19th, and the return showed that the project had an estimated cost of £335,00 covering a distance of 23 miles and 2 chains. The bill finally passed its final hurdle on June 14th, when a Select Committee of the House of Lords assembled to consider the bill. They heard that there was just the one opponent, Lord Vivian of Glynn House near Bodmin, who’s objection was in regard to an embankment of ornamental tree’s which had been built to his insistence by the Cornwall Railway, to which he feared being partially destroyed by the new line. The committee having weighed up all sides finally passed the resolution that the preamble of the Bill had been proved, but they added the proviso that there should not be a second passenger or goods station or lengthen that of the Cornwall Company. Also that they should continue the embankment so as to screen the new line as far as possible from Lord Vivian’s house. Two days later the Bill was successfully read for the third time in the House of Commons. However, at the meeting of Launceston Town Council on June 23rd, a motion to apply a change in the gauge from narrow to broad was passed 8 votes to two. This didn’t effect the passing of the Bill which received its royal assent on July 30th. Part of the scheme entailed the South Devon Railway being compelled to lay down a mixed gauge line between Lydford and Launceston.

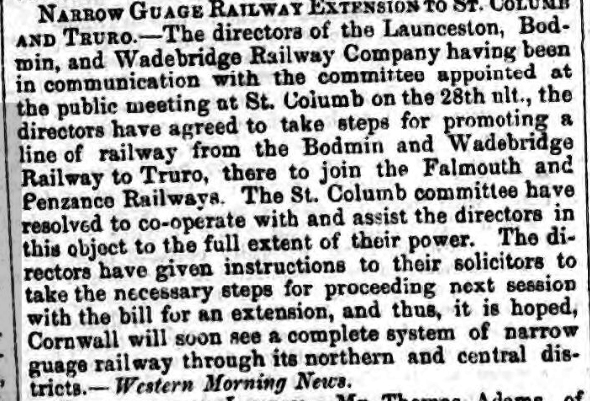

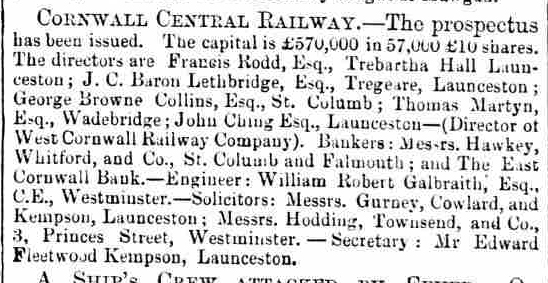

However, with the granting of permission there was very little progress in beginning the process of building the railway. Such was the wild eyed ambitions for railways, and a wide clamour for a railway link from the parishes and towns that an ambitious plan was put forward by Launceston solicitor Mr. Charles Gurney before even any prospect of the original scheme being built. The new proposal was to extend via the aforementioned Ruther Bridge junction and terminating by a junction with the then Cornwall Railway at Truro. This in effect postponed the start of any planning or granting of contracts as the companies board decided to await the result of this new application. However, this did not stop the company from appointing the well renowned civil engineer William Galbraith to overlook the prospected scheme and offer his weight to the argument of which he gave a positive outlook at a meeting held at St. Columb on March 2nd, 1865, where he stated that “not a year should be let slip.” Such was his personal conviction for the scheme, Galbraith sent down a team of engineers to look at the prospected route of 22 miles and 6 furlongs, and gave a qualifying seal of approval on it. This would increase to 23 miles with a branch. The cuttings, the deepest of which would be about 8 miles from the commencement of the line, would be about 48 feet deep, and the highest embankment would be 53 feet, there being a drop or short valley; that valley was near Truro, over which there would be a viaduct of 15 arches, running parallel with the viaduct of the Truro line. The steepest curve would be 3 furlongs 30 chains, and the gradient 1 in 60, which was quite normal on railways.

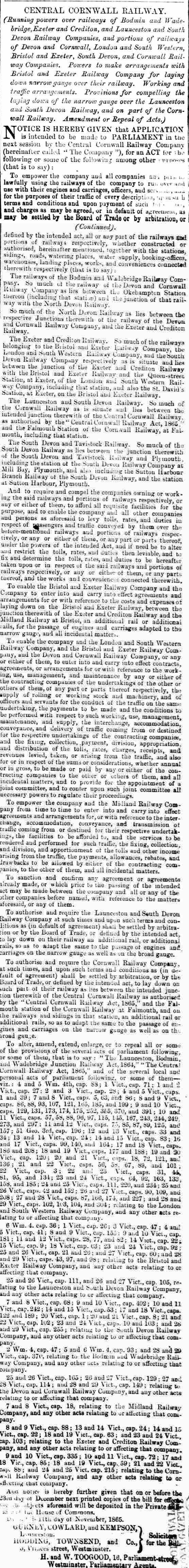

On March 15th, over a two day hearing, the extension Bill went before the House of Lords Select Committee with Mr. Phinn, Q.C., Mr. Field, Q.C., and Mr. Wilkinson being retained for the promoters and Mr. Burke, Q.C., and Mr. Somerset for the petitioners against. After many representations in favour, amongst who were Mr. John Tremayne, J.P., of St. Austell, and Charles Gurney who gave a forceful two hour speech, the Committee heard from the objectors which included the traffic superintendent and deputy chairman of the Cornwall Railway, Mr. Cockshott, and Mr. T. Woolcombe respectively. Mr. Woolcombe argued that in his opinion, the Cornwall line was sufficient for the traffic available and “if a line were made at half the cost of their own, and saving 33 miles in the journey to London, it might enable cheaper rates to be effected,” any competition, he felt,would be prejudicial to both companies. Mr. Burke, Q.C., in his address stated that “by the Cornwall line every town of importance had been accommodated, whereas the proposed line would avoid the principle towns, and run through barren wastes.” After hearing all representations the room was then cleared, and after an absence of a few minutes, their lordships declared the preamble proved and the bill passed. When the news of the decision reached Launceston by telegram, the bells of St. Mary’s Church rang several peals, and one of the bands struck up a parade through the town.

The bill was read and passed for the third time before the House of Lords on Friday, April 7th, being passed across to the House of Commons for its first reading, being then referred to examiners of petitions for private bills. The Cornwall Railway Company continued their objections, posting their petition to Parliament on April 29th. The bill received further backing at the beginning of May, when the Truro City Council gave it its backing and sending a memorial to parliament. The bill then got its second reading in the Commons on May 16th, being then committed. The bill was duly passed and was given its royal ascent on July 6th. This proved, however, to be the hiatus for the scheme as it struggled to raise the necessary funds and no work followed for the preceding three years, with extensions to the time period being sought each November. Under the Abandonment of Railways Act of 1850, a Warrant of the Board of Trade authorized the abandonment of the Central Cornwall Railway on March 16th, 1870.

Visits: 112