.

For many people, the Southgate Arch is as much a part of Launceston as is the Castle but without the former, it obviously wouldn’t exist. The Southgate, however, was only one of three gates to the old town with a Northgate and a Westgate giving access to the outside world and date from the time when Launceston was the only walled town in Cornwall. There was no need for an Eastgate due to the steep incline leading up from the Kensey Valley. There was one further entrance through the South Keep gate. It was essential that the gatehouse should be strong enough to ward off any attacks from outside and to this end, it had a portcullis, drawbridge and moat. Two Keepers were employed and they were responsible for the raising and lowering of the drawbridge at the necessary times, and for keeping the mechanism in working order.

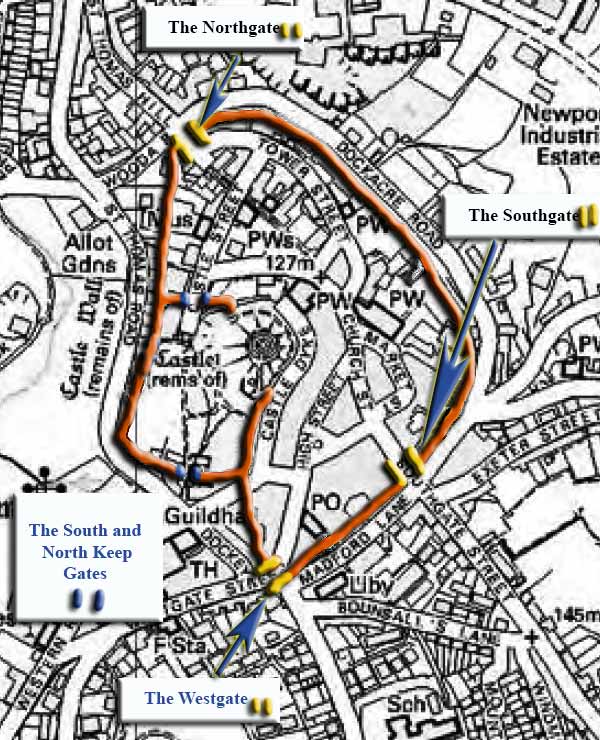

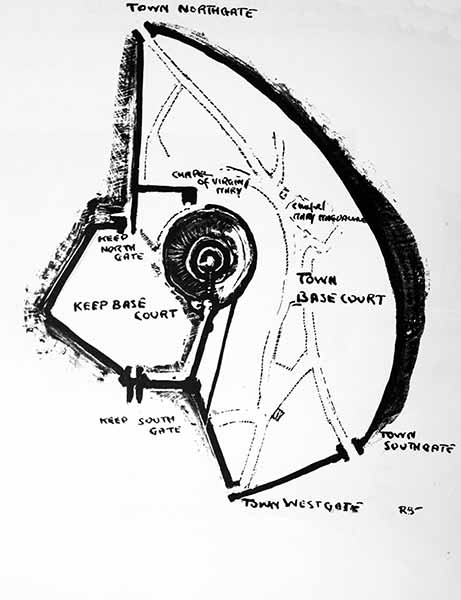

The Town Wall

The above map gives a rough idea of the town walls travel and the positioning of the Gates. It’s useful to bear in mind that the road network is somewhat different to what we have today. For a starter St. Thomas and Western roads never existed until the mid-nineteenth century, so access through the town from the west would be via Chapple (Called this after St. Johns Chapel which was situated there) then onto a small stretch of what is now Western road and in through the Broad and High street joining Church street then Northgate street through the Northgate and then there was a choice of either going down the steep St. Thomas hill or turning left into Wooda road. The left turn was very sharp due to the narrow road and the Northgate’s position at the junction. The Wooda road route would have taken the traveller right along Wooda road into what is now Wooda lane (the road by the National school came straight up at that time but with quite a steep incline.) Coming from the south the route would have taken in Whyte lane (now Race hill) through the Southgate and then Church Street, Northgate street ending with the same options as the western route. Much of today’s road are at different heights from what they once were, mainly to take the worst out of the many inclines which would have proven to be treacherous for horse and cart.

The wall itself had an average thickness of 6 feet and its entire length including the Keep Courts boundary exceeded 6 furlongs. In 1883 Otho Peter described it as thus; “ On the north, the junction was certainly near the Doomsdale prison, and descended thence, in a slightly curved line, behind the ‘Eagle House,’ now the property of John Dingley, Esq., to the Northgate. From the Northgate, the wall continued over sites occupied today by the Bible Christian Chapel, by Northernhaye the residence of the writer, by the Lower Walk along the front of the present Town Clerk’s (His father Richard Peter) ‘Cottage,’ thence through Mount Pleasant, on by the eastern boundary of the Vicarage Garden to Blindhole and the existing Southgate. From the Southgate, in an almost straight line by modern Madford Lane, to the Westgate; and from the Westgate, over the sites of Mr Vivian’s dwelling-house, and the Livery Stables below it, too (as we think) the Watch Tower, and there joining the Keep Court wall.” He added “Between the North and South Gates the ground outside the wall sloped rapidly downward; between the South and West Gates the ground as rapidly ascended ‘Dunheved hylle.’ From the Westgate, by the ‘Dockey,’ to the Watch Tower the site was almost level. A protecting fosse or dyke from the Southgate to the Westgate was continued along the ‘Dockey’ to the Watch Tower. The open space now occupied by the streets of the town formed originally a Base Court to the Castle. In that Court, by the wall between the North-east Gateway and the Guard Tower, ran the Castle dyke, or Castle ditch, which is frequently mentioned in our town accounts. This dyke was connected by a sluice with the dyke in the ‘Dockey.’”

Above Launceston Town Wall at Angel Cottage which backs onto the Blindhole . Photo courtesy of Emma Smith.

As we are fully aware today we have just the one Gatehouse left, the Southgate, so what happened to the Westgate and Northgate. The Borough accounts for 1381 the Westgate is shown to be in charge of a single keeper. In 1384-5 and subsequent years, to 1403, two keepers held it. On the 25th April 1646, immediately after Fairfax took possession of the town, it was repaired. With the Westgate guarding only the direction of Bodmin and West Cornwall and was protecting this side of the town in conjunction with the stronger built South West Castle Gate and the Watch Tower (the Barbigan, or Barbican), it was of comparatively less importance than the South and North gates and as such, its maintenance was never given precedence. It seems that the Westgate was in quite a ruinous state by about 1709 so what remained was pulled down at around this date. Immediately outside the Westgate was the famous ‘West Well’. It has been suggested that its abundant flow of water might well have supplied the adjacent moat and the ordinary needs of the Castle. Folklore has hinted of an underground passage from Higher Madford (Bounsalls Lane) to the base of the Castle Keep, and thence to the site of the Priory at St. Thomas, and Richard and Otho Peter in their 1883 publication ‘ Histories of Launceston and Dunheved,’ suggested this may have derived from either in provision actually for conveying water from the higher level, or from the fact that at some time period an assaulting army had driven a mine under the wall from the southern side.

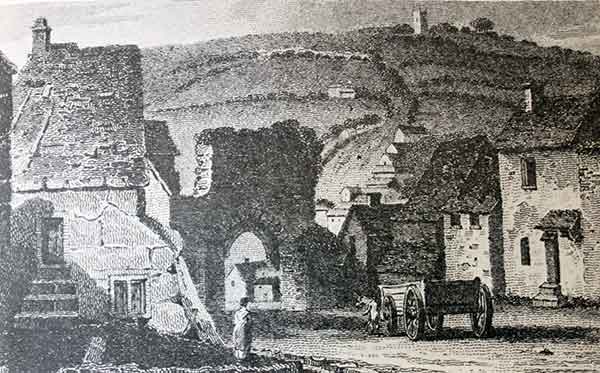

The Northgate

Launceston’s Northgate.

The Northgate protected the town at its only approach from Stratton, Holsworthy, and the North Coast. It stood midway across the slope of the steep hill ascending from Launceston Priory and Newport, through what was then Bast Street (St. Thomas Hill), and (within the gate) through the Northgate Street and Castle Street to the tower of St. Mary Magdalene. The type of the arch was the same as the Southgate, but of less depth. It was apparently not more than 10 or 12 feet through. The upper part of the wall on each side of and over the arch in 1808 was said to be in a dilapidated condition. The North Gate was in charge of Walter Tolla and

William Horn in 1381; of John Choke and Walter Tolla in 1384; and in 1385 of John Choke and William Coulyng. In 145 1 timber was bought and wages were paid for “repairing the North Gate,” and for making “ pitts ” there. In 1587 “the east syde of the North Gate” was alleged to be greatly in decay. In the mayor’s account for 1809-10 are these entries: “Paid for 303 feet of worked stone from Alternon moors for the Northgate battlement, at 14d. per foot;” and, “Paid for a new vane for the gate £3 5s.” With its position at the bottom of Northgate Street and the junction with Horse lane (Dockacre road), St. Thomas Hill and Wooda Road it was proving to be of a considerable nuisance, particularly for those wishing to turn from or into Wooda road as the turning was so sharp many a wagon struggled. And so with the building being in a poor state of repair the decision was made to demolish the Northgate in 1832 even though that by this time the construction of the new King William Road (St. Thomas Road) had somewhat alleviated the need for traffic to negotiate the junction.

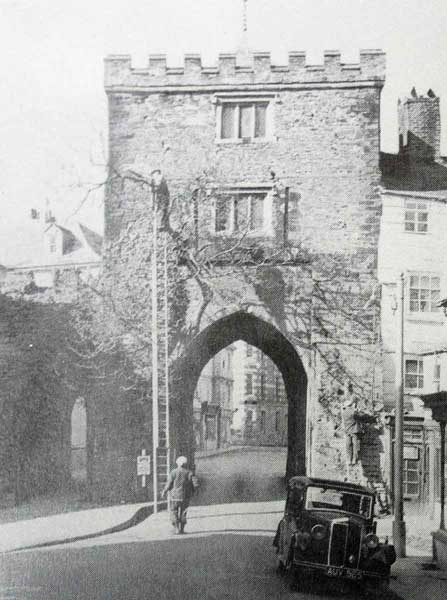

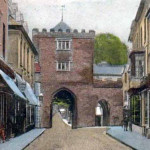

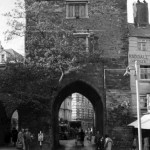

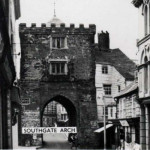

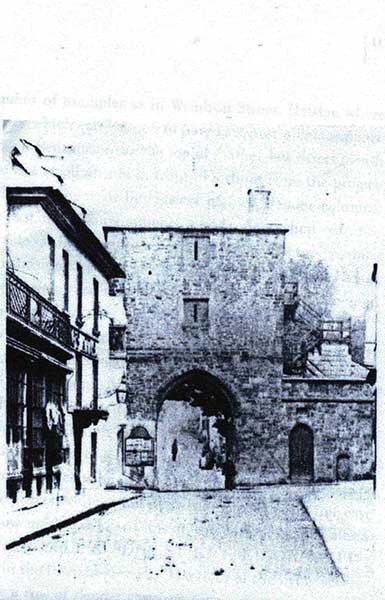

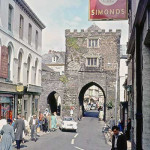

Above two views of The Southgate before its refurbishment and the adding of the battlements and pedestrian arch in 1880s.

And so the Southgate is left as the last remaining medieval gateway into Launceston. The gate faces what was Whyte Lane (Race Hill) and the direction of the most likely attack with the approaches of Tavistock, Plymouth, and Exeter. It was therefore essential that the defence should be strong and the Southgate was most certainly constructed with this in mind. Outside it was the moat and drawbridge. The arch of the gateway measures at its external base 24 feet, inclusive of the opening. The archway itself is of the depth of 27 feet 6 inches. Its elevation averages 18 feet. The exterior of the wall is supported by two massive buttresses. The arch is ribbed within by cut stone. Between two of these ribs is a vertical aperture of 6 feet 4 inches through the whole breadth of the arch. This aperture creates the appearance of a divided or double arch, one within the other; and, indeed, there are reasons for supposing that the outer portion of the arch is more ancient than the portion next to the town. Besides the ponderous portcullis which occupied part of the aperture, there were other important uses to which it was applied. Among these was the suspension of a strong door by which the passage could suddenly be closed. The portcullis, it will be remembered, was a strong framework of timber, united in the form of a harrow, and pointed with iron at the bottom. It was raised and lowered by machinery in the keeper’s chambers over the arch. There were two such chambers above this arch, each approached by a staircase, which led also to the promenade on the wall. The highest point of the whole building was about 38 feet above the ground. Near the middle of the sixteenth century, the two chambers were displaced from the purpose solely of fortification.

In 1446 the Town spent £3.8s.01/2d in cleaning and repairing the Arch which may have helped it remain in good repair compared to the Westgate. The early eighteen hundreds saw it as a house of detention – a gaol for petty offenders and a prison for debtors. The top storey was for debtors but this was rarely used because of the scandalous conditions; rather than confine them in such a dungeon many local tradesmen let their debtors go free. The lower room was for criminals and, like the room above, was in a filthy and dilapidated state. No fire was allowed, sanitary conveniences were unknown and water had to be brought in by the jailer when it suited him to do so.

In 1827 matters came to a head when five suspected burglars were refused bail and had to remain in the dark house – as it was known – with only one bed between them and without ventilation or comfort of any kind. The Home Secretary was notified of their plight and an order was issued for their immediate release on bail and that the prison be refurbished. However, ten years after the demise of the Northgate, moves were being made for the Southgate to experience the same fate. Mr Hughes a Barrister and the town mayor at the time was asking fellow members of the borough council, at the prompting of the town clerk Mr C. Gurney, to sign a memorandum for the removal of the Southgate. Fortunately, Mr Richard Peter was at hand and he refused to sign the memorial pointing out its historical importance. Mr Gurney at that time owned and inhabited Madford House, which was just around the corner where the Castle rise dentist and the old Tax office are now located. Richard Peter started a campaign to save the Southgate by calling Public meetings as well as pleading with the Duchy of Cornwall and as he put it ‘countered the vandalism’. He fortunately succeeded.

With the closure of the prison in 1884 the Town Council resolved that it should become a Museum and duly voted funds for its repair and improvements. A bakery, run by the Poad family beside the Arch, was purchased by Richard Peter who had it demolished and to a design by his son Otho Peter and built a smaller Arch with pedestrian footpath for easier access to Southgate Street. Extensive improvements were made inside with battlements around the top of the Gateway and a plaque on the side of the building commemorating Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee completed the refurbishment. With the work completed in 1888, the Museum duly opened in January 1889.

It was the Town’s Museum until the 1950s, then an antique shop for a number of years, followed by being used as a Gallery for the Arts and most recently a Photographic Studio. Today the building is vacant. (Taken from Launceston Town Council Southgate Arch page).

As previously mentioned until the construction of Western and St. Thomas road’s in the early 19th century, the main route towards Bude and Holsworthy was straight down Race Hill, through the Arch and down over Northgate Street and St. Thomas Hill. In more modern times when Southgate street was two way the traffic was directed by point duty on Treleaven’s corner and for many years this was undertaken by the reliable gentleman Tom Sandercock (below left). No one batted an eyelid back then to see the cattle lorries trundle underneath the Arch with barely daylight to be seen with the Arch bearing the scars of the decades of traffic that has driven through. But it still stands much to the testament of Richard Peter, but also as a reminder Launceston’s importance as the county town of Cornwall as commemorated by the bronze plaque placed in the pedestrian way by the Town Council (below right).

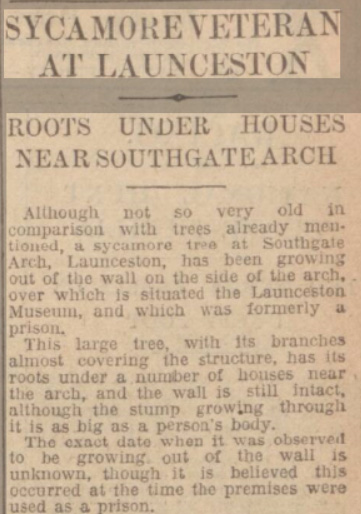

For many years a sycamore tree was synonymous with the Arch growing as it did from out of its masonry. It is thought that the tree dated back to when it was still in use as a prison so by the time it was cut down, with some outcry in 1953 (below), it was at least 70 years old.

Its roots were well established and were damaging the structure of the Arch as well as nearby buildings so there was no alternative but to remove the sycamore.

The Southgate Gallery featuring 60 images from the late 19th century upwards.

Visits: 483