.

The Battle of France began on May 10th 1940, with the Wehrmacht launching an invasion of Belgium, the Netherlands and France. By May 20th, German forces had reached the English Channel, and on May 28th, the Belgian Army surrendered. The combination of the large-scale combined operations mounted by the Wehrmacht during the invasion of Norway in April and the prospect that much of the English Channel coast would soon be occupied made the prospect of a German invasion of the British Isles alarmingly real. Fears of an invasion grew rapidly, spurred on by reports in both the press and from official government bodies, of a fifth column operating in Britain that would aid an invasion by German airborne forces.

The government soon found itself under increasing pressure to extend the internment of suspect aliens to prevent the formation of a fifth column and to allow the population to take up arms to defend themselves against an invasion. Calls for some form of home defence force soon began to be heard from the press and from private individuals. The press baron Lord Kemsley privately proposed to the War Office that rifle clubs form the nucleus of a home defence force, and Josiah Wedgwood, a Labour MP, wrote to the prime minister asking that the entire adult population be trained in the use of arms and given weapons to defend themselves. Similar calls appeared in newspaper columns; in the May 12th issue of the Sunday Express, a brigadier called on the government to issue free arms licences and permits to buy ammunition to men possessing small arms, and the same day, the Sunday Pictorial asked if the government had considered training golfers in rifle shooting to eliminate stray parachutists. The calls alarmed government and senior military officials, who worried about the prospect of the population forming private defence forces that the army would not be able to control, and in mid-May, the Home Office issued a press release on the matter. It was the task of the army to deal with enemy parachutists, as any civilians who carried weapons and fired on German troops were likely to be executed if captured. Moreover, any lone parachutist descending from the skies in the summer of 1940 was far more likely to be a downed RAF airman than a German Fallschirmjäger.

Nevertheless, private defence forces soon began to be formed throughout the country, often sponsored by employers seeking to bolster the defence of their factories, and placed the government in an awkward position. The private forces, which the army might not be able to control, could well inhibit efforts of the army during an invasion, but to ignore the calls for a home defence force to be set up would be politically problematic. An officially-sponsored home defence force would allow the government greater control and also allow for greater security around vulnerable areas such as munitions factories and airfields, but there was some confusion over who would form and control the force, with separate plans drawn up by the War Office and General Headquarters Home Forces under General Kirke.

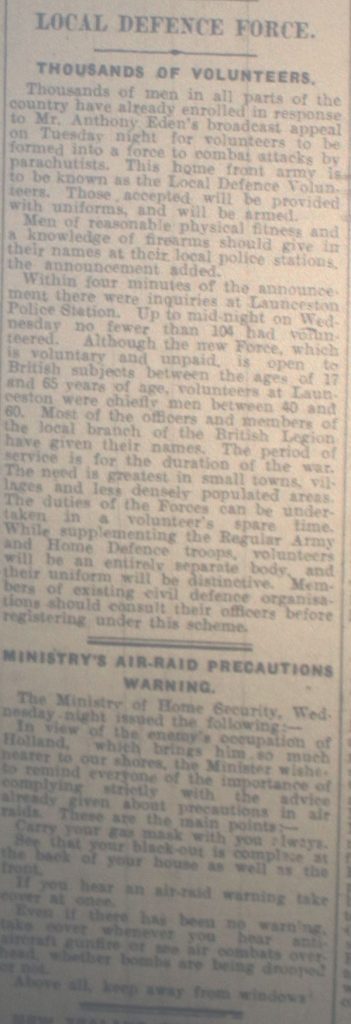

The government and senior military officials rapidly compared plans and, by May 13th, worked out an improvised plan for a home defence force, to be called the Local Defence Volunteers. The rush to complete a plan and announce it to the public had led to a number of administrative and logistical problems, such as how the volunteers in the new force would be armed, which caused problems as the force evolved. On the evening of May 14th 1940, Secretary of State for War Anthony Eden gave a radio broadcast announcing the formation of the Local Defence Volunteers and calling for volunteers to join the force: “You will not be paid, but you will receive a uniform and will be armed“.

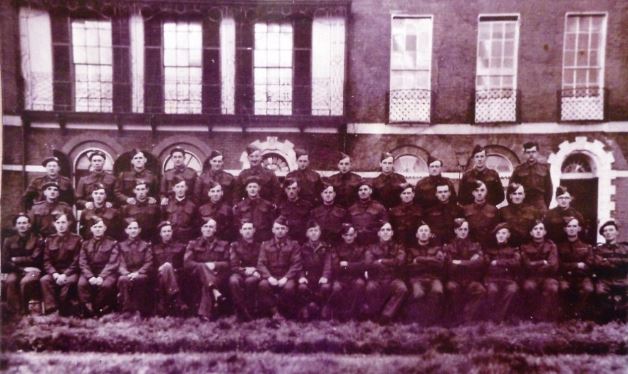

In the radio announcement, Eden called on men between the ages of 17 and 65 in Britain who were not in military service but wished to defend their country against an invasion to enrol in the LDV at their local police station. It was anticipated that up to 500,000 men might volunteer, a number that conformed generally with the Army’s expectation of the total numbers required to fulfil the functions expected for the new force. However, the announcement was met with a great deal of enthusiasm on the part of the population, with 250,000 volunteers attempting to sign up in the first seven days, and by July this number increased to 1.5 million. (source Wikipedia) Within four minutes of the announcement, there were inquiries at Launceston Police Station and up to the midnight on May 15th, no fewer than 104 men had volunteered. Most of the men that volunteered were aged between forty and sixty with the officers and members of the Launceston British Legion being the first to give their names.

Within weeks of the call for Local Defence Volunteers, over 500,000 men had come forward. Under the regulation, the volunteers became part of the Armed Forces of the Crown, ranking as soldiers, with soldiers rights, and a soldiers obligations. Rifles were issued but not in large enough numbers, so it was envisaged that 12-bore shotguns would be more than efficient and serviceable for much of the duties. A plea for owners of 12-bore shotguns to come forward and lend their weapons to the L.D.V. was made on June 22nd whilst at the same time, the LDV was officially renamed the Home Guard. Armlets would now bear the initials ‘H.G.’ The response to the appeal for recruits had been so good that the strength of the force exceeded 1,300,000 men. Due to this, it had been decided to temporarily suspend recruitment, except in districts where the strength had not met immediate requirements. The reasoning for this was to enable the provision of equipment to be pushed forward and allow commanders time to assess their requirements and remedy any defects that came to light.

The Home Guard had a number of secret roles. That included sabotage units who would disable factories and petrol installations following the invasion. Members with outdoor survival skills and experience (especially as gamekeepers or poachers) could be recruited into the Auxiliary Units, an extremely secretive force of more highly trained guerrilla units with the task of hiding behind enemy lines after an invasion, emerging to attack and destroy supply dumps, disabling tanks and trucks, assassinating collaborators, and killing sentries and senior German officers with sniper rifles. They would operate from pre-prepared secret underground bases, excavated at night with no official records, in woods, in caves, or otherwise concealed in all sorts of interesting ways.

They concealed bases, upwards of 600 in number, were able to support units ranging in size from squads to companies. In the event of an invasion, all Auxiliary Units would disappear into their operational bases and would not maintain contact with local Home Guard commanders, who should indeed be wholly unaware of their existence. Hence, although the Auxiliaries were Home Guard volunteers and wore Home Guard uniforms, they would not participate in the conventional phase of their town’s defence but would be activated once the local Home Guard defence had ended to inflict maximum mayhem and disruption over a further necessarily-brief but violent period.

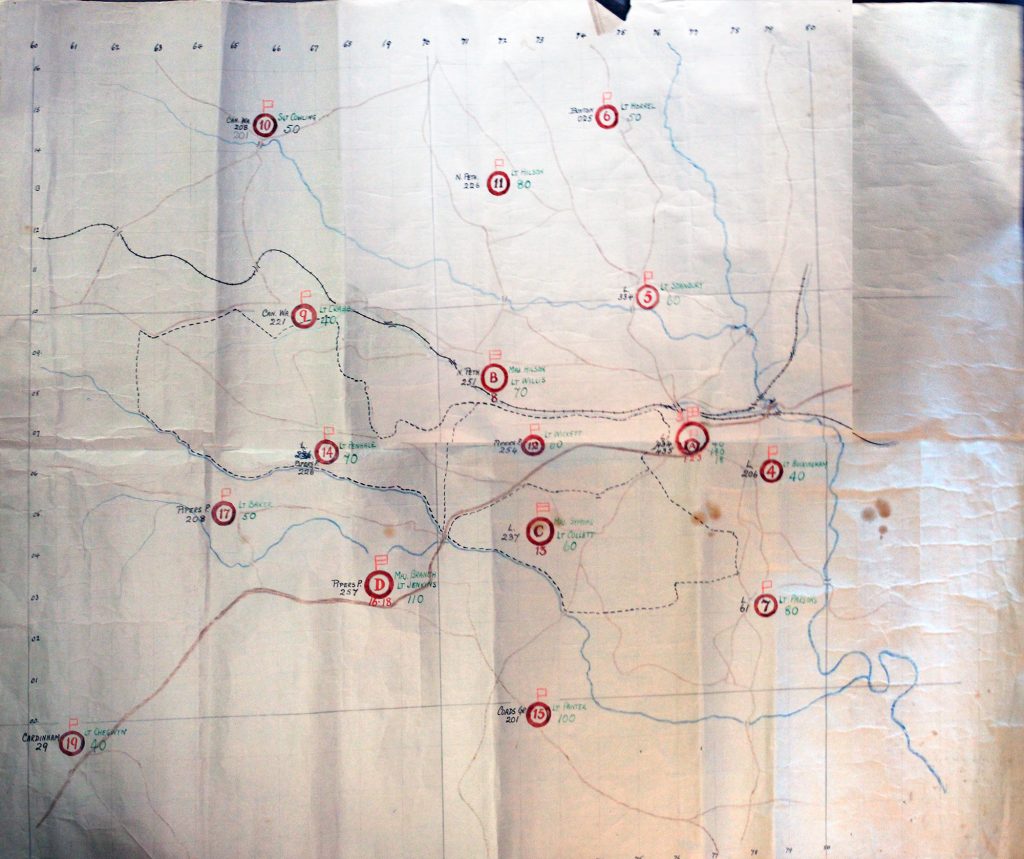

After 1941 a “grouping” system was developed where some patrols within a demographic area would train together under more local command. Launceston and Coads Green was part of group 6 along with Morval (Looe), Liskeard, St Germans, Pelynt, Lansallos, Menheniot, St Keyne and Bridgerule (now in Devon). They were under the group command of Captain G. H. Sergeant from Liskeard along with Lieutenant W. Crichton (discharged May 1944 due to ill health) and 2nd Lieutenant J. F. William Mewton. (Source British Resistance Archive)

Launceston Auxiliary

Sergeant George H. Sanders

Corporal Alfred C. Mounce and his older brother

Reginald R. Mounce

Sydney Hill

Albert E. Pauling

Richard H. Wearing

Thomas H. Trewin

Coads Green Auxiliary

Sergeant Walter Tucker

A. Douglas Murray

S. Jack Gribble

W. Leonard Brent

S. Jack Creber joined H.M. Forces in April 1943

F. Alan Gillbard

Arthur F. Harris

and possibly Sydney T. Palmer

Even once the threat of invasion in 1940 had passed, the Home Guard remained in existence manning guard posts and performing other duties to free up regular troops for duties overseas, especially taking over the operation of coastal artillery batteries and anti-aircraft batteries (especially rocket batteries for the protection of key industrial sites). In 1942, the National Service Act allowed for compulsory enrolment in the Home Guard of men aged 42 to 51 where units were below strength. Meanwhile, the lowest rank within the Home Guard, ‘volunteer’, was renamed to ‘private’ to match the regular army usage.

Eldred Broad of Dutson Farm remembers the men being armed with their twelve bores and an L.DV. armband grouped together in each parish, soon after they were issued with uniforms and rifles etc and then renamed the Home Guard. Three or four members were stationed in a small hut at Tipple Cross (just above Netherbridge) each night to stop and check whoever was passing. As time went on anyone young enough who had not volunteered was conscripted. They trained on evenings and Sundays.

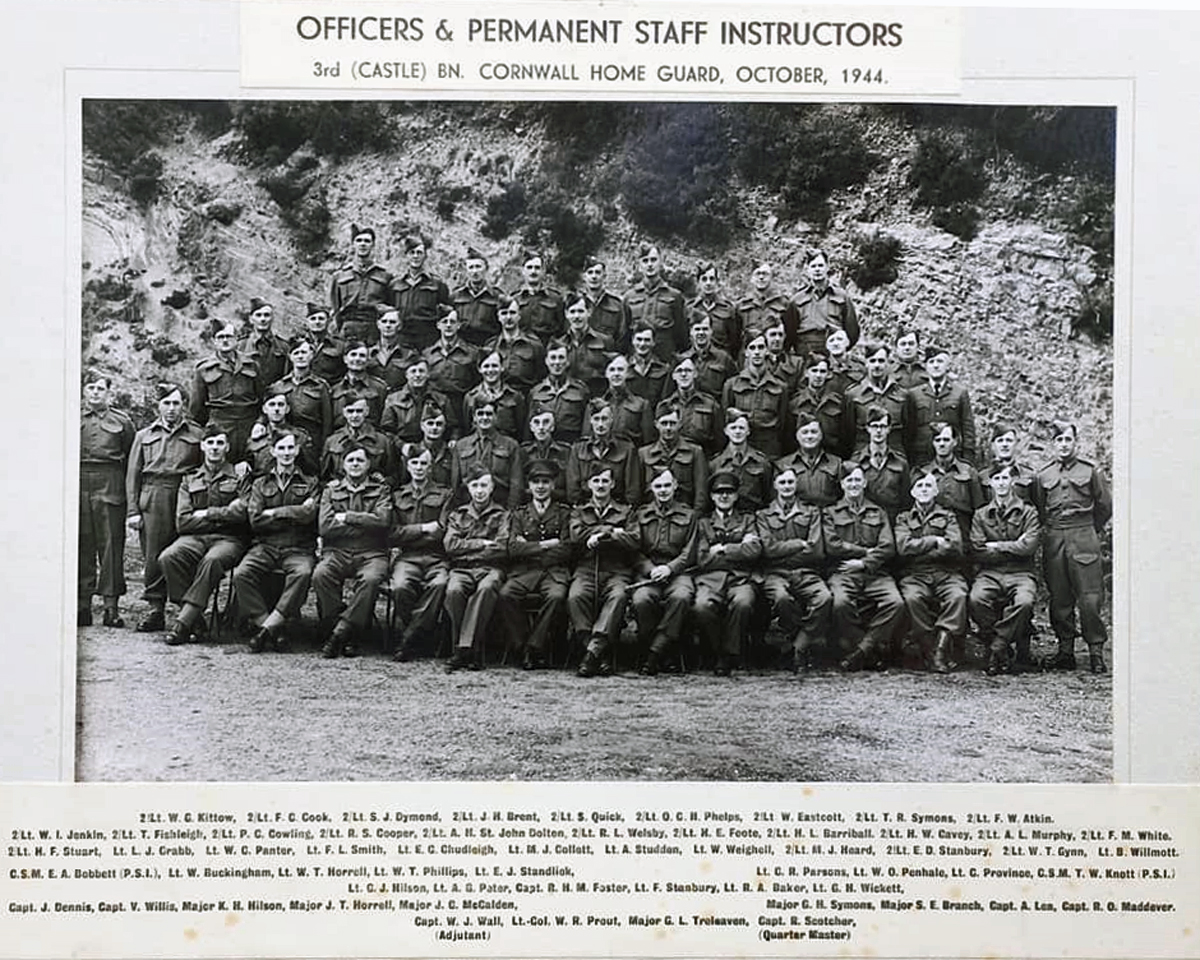

The officer in charge at Tresmeer was Lt. Tamblyn, the headmaster of the school. Each village had a platoon and the overall command lay with Major Treleaven who lived at Moor View, Egloskerry.

Jim Cory who enlisted with the Tresmeer Homeguard once he was sixteen, was on duty the night that the Germans bombed the oil depot at Torpoint and can remember the light from the fires was so bright that the watch could read a newspaper outside their watch hut.

One weekend it was decided to hold a night-day exercise at Bolesbridge in North Petherwin. The object of the exercise was to capture Launceston Castle which was being guarded by the regular army. There were some 150 Home Guard members on the bridge talking etc. when there was a commotion. Some of the NCOs had been taken upstream to Bodgate Farm and they had followed the river down to the bridge. They were armed with thunder flashes and threw them out into the group of men standing around. It was very frightening but certainly showed us what would have happened if it had been Germans with hand grenades.

At the beginning of March 1943, an exercise took place whereby the Home Guard in Launceston came under ‘attack’ by a detachment of Commando troops who landed at a South-West port in Cornwall. The Commando’s who had spilt into small groups made their way to Launceston with the intention of destroying their objectives before a fixed set time. Having destroyed their objectives they were to endeavour to withdraw as quickly as possible to their re-assembly points. The task of the Home Guard was to completely destroy the enemy troops before they reached their objectives, and further, in the event of any reaching their objectives, to destroy them before they were able to reach their re-assembly point. Co-operating with the Castle Battalion Home Guard under Major W. R. Prout were units of the Lifton H.G., Post Office and Railway H.G., and the Police. The Commando troops moved so quickly towards their objectives that it was necessary to call out the H.G. many hours before it was anticipated they would be required to cope with the ‘invader.’ This unexpected call-out of the H.G. proved to be a very successful test, and a large percentage were on duty at the new zero hour. Information was received of the movements of the ‘enemy’ practically during the whole of their journey from their starting point, by the Police. As the Commandos entered the Battalion area many prisoners were captured, and the whole objectives were carefully guarded and patrols sent out to round up the enemy and generally made conditions as difficult as possible for them. At a late hour on the first night of the operations, the H.G. were called off for the remainder of the night, and the district next day had the unusual spectacle of seeing many H.G.’s at work in their uniform, standing by ready at a moment’s notice to at once proceed to their allotted points. Due to this being an exercise, it was not possible for the H.G. to engage for the whole of the day-light hours, with the consequence that some of the objectives were ‘destroyed’ by the enemy.

Towards the evening of the second day, the Home Guard were once again fully engaged with the raiders, and this second night were mainly engaged with the Commandos, who commenced their attack from the North-West, and who had come through from a port in Somerset. During the second afternoon, information came in freely from Home Guards in the country areas as well as from the Police and enabled the Battalion Commander to take the necessary measures to cope with the situations. Many districts were combed and swept in their search for the raiders, who were harried and harassed on every hand, and during the night hours, a steady flow of prisoners were brought in to be questioned by the Intelligence Officer. The operations were continued into the small hours of the next day until only a small number of commandos were not taken free. The exercise was mainly for the benefit of the Commando Troops, who in this particular case were not allowed to use any transport, and who had orders not to use roads and villages. One of the points to come out of the exercise was the amount of information that was provided by the general public. In the debrief that followed one of the captured Commandos commented when brought in, “heaven help Jerry if he comes to Cornwall; you can’t move or breathe without there is a Home Guard waiting to finish you off.” The Brigadier Commander of the Cornwall Coastal Area said of the exercise, “I would like to send a word of congratulations to the Group in general and to the Castle Battalion. In particular on the excellent work done in the recent Commando exercise. It was quite first-rate and all ranks showed splendid keenness.”

“In the years when our Country was in mortal danger, (name) who served (dates) gave generously of his time and powers to make himself ready for her defence by force of arms and with his life if need be.“

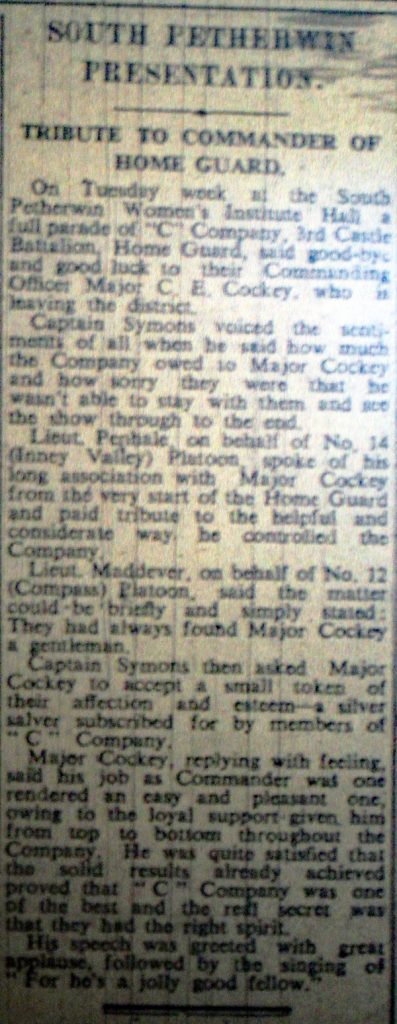

The various units around the district then began to disband, holding their respective ‘stand-down’ ceremonies.

Roy Olver’s Homeguard experience.

Tresmeer Homeguard member Frank Bate

Visits: 164