.

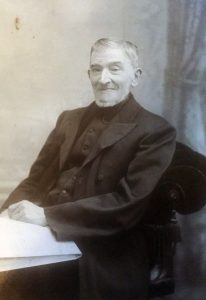

These are the reminiscences of Launceston from 1820 to 1830 kept by Richard Robbins in a journal which he passed on to his son Sir Alfred Robbins in May 1895.

I was born in 1817. My first impressions was the funeral of Mr. John Hender, husband of Mrs. Wilmot Hender, of St. Thomas hamlet, in 1820, my parents lived two houses above them.

My next impression was the coronation of George the fourth in 1821, when with my parents and sisters we took luncheon in the Middle Walk. The Mayor, Corporation, gentry, tradespeople and the working classes of the town were all present. I, who has a good recollection of the orchard that was turned into a Wesleyan cemetery in 1822, when the apple trees were cut down. A boy like myself went in and jumped over the trunks of the trees. The first funeral that took place there, was in 1823, and my impression it was Mrs. Dingley, wife of Mr. Richard Dingley, of Broad Street, grocer and watchmaker.

This was a period that when few or if any improvements took place. For centuries men had lived and also passed away without seeing any sign of improvements, and if there should be a chance to leave home if it was for a long period, there was not a house built, no, not even a cattle shed, and the place and the people were pretty much the same as when they left it. This was a period of great trial to the industrious classes, a four pound loaf was 10d, sugar one shilling the pound, raisins and currants about the same price as the latter, salt 4/- per pound, soap about the same price as the latter. Outside garments were very expensive. The principle or most of the labouring people had to fall back on second hand clothing, and at the same time work was scarce and wages low, so low indeed were the wages at this time, not only of agricultural labourers but artisans as well, that the great bulk of the working classes were in a state of some pauperism. To the agricultural and working classes the conditions of life was so hard that it is a wonder they managed to live at all. Most artisans and labourers in the town kept a pig in order when fat, to sell it to the butcher. The money would fund the payment of their yearly rent and in the spring of the year, they would take from a neighbouring farmer 20 or 30 yards of potato ground, for their winter supply, and generally two would club together and buy a bag of wheat on the market day and sent it to the grist miller, to be ground and the husk only taken from it, so the bread they had to eat was of a very course kind. The agricultural labourer similarly kept a pig, to feed for his yearly family consumption, for the year, his wages averaging eight shillings a week, and in some parishes so low as seven shillings a week, these scanty earnings, they seldom or ever could buy fresh meat from the market (except at Christmas, or at Whitsuntide) and his employer compelled him to take his corn and barley from him. The price all the year round he had to pay for it was 16 shillings per bag for wheat, and 6 shillings per bag for barley, whatever the market price was.

The dwellings of the working classes was deplorable in many cases, in the town they were huddled together like pigs, it was not very many of them that had got more than one room to live in, with no closet to the houses and to fetch their water from the pump or conduit, and of a dry season to fetch the water from the river or the quarry well. Their dwellings almost with exception were in a wretched condition, with most of them having been much out of repair. On the ground floor you would find most of them with broken slates and the next floor above could be seen through, not a scrap of matting, much more a bit of carpet to be seen in any of these homes and if they ever heard of paper hangings they would not know what it meant. The wood work was never painted, occasionally a little white wash. White lime had to be fetched from Morwellham, it cost 2shillings a bag and seldom could you get it at that price and if brought from Plymouth it would cost in carriage 1/6 per hundred weight.

Coals were very dear, they had to be brought from Bude and Boscastle, before they could be had at Druxton. There is an entry in the corporations books of 1824; paid £.4..12.. for a ton of coals, very few had grates in their chimneys. Faggot wood was the principle fuel. Coal was sold by the peck or gallon, 10d. for the former and 2 ½d. for the latter.

(Druxton wharf, near Werrington, was the Launceston end of the Bude canal, completed in 1823.)

I well recollect the political scare from 1827 to 1829. There was then a great agitation to allow the Roman Catholics to Parliament, that if the Bill passed, Protestants would never be safe in their beds, and a risk to us all of being burnt to the stake as our forefathers had suffered, and this bogey was readily believed in by the lower classes. There was not then any newspapers for them to read and no board schools. It was spread by the Orange Party and their satellites. (The Catholic Relief Act was passed in 1829).

During this period there was a great gulf between the higher classes, and the lower classes, the former was ‘rich people’ the tradesman was ‘common people,’ the workers ‘poor people,’ and if a few collected together that would be called a mob. Parish apprenticeship was then in full swing, and in its most demoralizing form. (Parish Apprenticeship; a scheme originating under Elizabethan Poor Law provide training for pauper children. An Act of 1767 aimed to correct the worst abuses of the system. The abuses actually got worse as the factory system developed in the late 18th century and early 19th century. Conditions for apprentices imporved only with the effective factory and mines acts of the 1930’s and 1840’s.)

I shall first take the corporation, their officials and appointments.

Rowe, Coryndon, Dockacre Doctor of Medicine

Roe, John Blindhole Retired Tallow Chandler

Roe, Phillip Blindhole Solicitor, brother of the above

Ching, John Broad Street Chemist and Wine Merchant

Penwarden, Richard Star Cross Saddler and Currier

Cook, John Scarne Retired Captain of the Royal Navy

Hockin, Parr Cuninham St. Thomas Solicitor

Green, James Broad Street Gamekeeper, for the Duke of Northumberland

His Grace the Duke of Northumberland Recorder

John King Lethbridge Madford Deputy Recorder, Solicitor, Agent to the Duke of Northumberland

Christopher Lethbridge Madford Town Clerk

Rev. John Rowe (Chaplain at Werrington)

Robert. Martin Organist

(Robert Martin was buried in St. Marys Church under the organ in 1830)

John Rowe Tailor and Auctioneer

(John Rowe committed suicide in the Exeter Inn hay loft, on Giglets Market in 1835. There was no appointment to fill his place. He was Leading town sergeant. Giglets Market was a fair held in Launceston on the first Saturday after Christmas. It was a wife market, a giglet being a giddy young woman.)

Town Sergeants

John Burt Shoe Maker

John Burt was taken prisoner on board the Swift Shore by the French in 1815. He was the Collector of the Dukes Tolls at the St. Stephens Fairs.

John Ralph Tailor

The Town Sergeants also acted as Constables, when required. John Rowe lead the Corporation, with a Long White Rod, The two others followed, with their Maces on the shoulder and had new cloaks and hats at every Mayor choosing.

Constables

Joshua Farthing Tailor

William Tapson Carpenter

William Grylls Roper

William Rogers Shoe Maker

Joshua Farthing was present when Jory was killed in the Execution of his duty at Bamham in 1814. He was the leader of the Cornish Militia Band and served in Ireland with them in 1812. He was a teacher of music, and the first to introduce the piano to the town.

Sexton

John Frayn Carpenter

Scavenger

Thomas Congdon Labourer

Thomas Congdon was the appointed whipper of malefactors to the carts tail and the pump, Broad Street.

(flogging at the cart’s tail was a punishment for the larceny; the procession started at Star Cross, went down the High Street, past the old Butcher’s Market, now Church Street, and back by Broad Street. The pump was close to the old assize courts in Broad Street. Flogging ceased to be applied in Launceston about 1834.)

Inspector of market Skins

William Bray Shoe Maker

William Bray had to examine all the skins in the market, if cut there was a two pence fine, all further cuts were one penny extra.

Parish Clerk

William Spevin Schoolmaster

Bell Ringers

John Frayn Tenor, Sexton

William Frayn Hatter

Robert Hodge Huntsman for the Duke of Northumberland

John King Carpenter

John Moyse Farmer

When Robert Hodge was buried in 1827, Rev. John Rowe wept in reading the service like a child. In fact he sobbed aloud. Hodge was the Dukes huntsman. Rev. Rowe was a constant follower of the hounds. His dress was top boots, white breeches (I believe buckskin), scarlet coat, and velvet cap. The Dukes hounds were kept at Newport at the bottom of Dutson Hill. The pack was broken up in 1834.

We ring the quick to Church, the dead to grave

Good is our use, such usage let us have.

Who swears or curse or in a furious mood

Quarrels or strikes altho he draws no blood

Who wears a hat or spurs or turns a bell

Or by unskillful handling mars a peal

Let him pay sixpence for each single crime

Twill make him cautious gainst another time.

The above was in large coloured letter on the wall of the belfry on the second floor where the ringers stood. Vandalism came in here why I don’t know, but this has occurred in several cases connected with what was Church property, the graves have been stripped of their head stones, to make pigs houses, the floor stones of the memoires of the dead that rested in the Church were used for footpaths, the monuments some of them when taken down when the Church was restored in 1850, were not all replaced. There was one of a lady that lay in the North Church yard for many years unbroken, the inscription on it was her four husbands, three of them were Devonshire Knights. In 1884 Mr. Powell, the editor of the Cornish and Devon Post, and myself went into the Church yard to look up this stone but after some time turning over a rubbish heap against the wall, we found it broken in three pieces when the Council room was rebuilt in 1850. Charles the First letter of thanks to Cornishmen, the letter was removed from in the open of the Blindhole, and placed up against the wall of the butchers market. The woodworm, rotting and the letters disfigured. I read a paper before the Launceston Mechanics Institute, Launceston past, present and future, and called attention to this neglect and scandal of the public property by the corporation. The Mayor on the following morning ordered it to be taken to Mr. Lines and repaired at his expense. When I was a young man there were nine fine chestnut trees in the Church yard, but where are they now? They are destroyed and by the hand that should have been their protectors.

New Shambles

The markets were not under the sole control of the corporation. The butchers market was most of it in the hands of private owners, viz the old shambles on the site of Mr. Haymans Toy Shop (what later became the orange tea rooms at No. 22 Church Street), the new shambles was at the London Inn yard (No.26/28 Church Street). The former was entered by three steps facing the Church, the entrance in Church Street at the higher end by four steps. The third entrance in High Street was at the upper end, level with the road. The new shambles had its entrance in Church Street at the upper end by a wide passage, it extended in the High Street with stalls on each side permanently erected on each side, and several of the butchers had stalls outside tradesmen’s shops, rented from the occupiers of High Street and Church Street, where the town could not levy tolls. The corn market was held in the old town hall, Broad Street. The cattle on four days were sold in the centre of the town, extending on Leonards Fair day (St. Leonards Fair, held on November 17th, was a major event in Launceston) to as far as the Ring of Bells (Northgate Street, closed in the 1930’s). The horses in season were sold through the streets.

Markets

The fish market in Broad Street was held on the left hand side, commencing from the corner of Southgate Street to Mr. Chings, chemist (No. 9, Broad Street). The vegetable stalls were in Southgate Street. Shoemakers were in Broad Street outside Mr. Rogers shop abutting the Town Hall and Mr. Richard Dingley’s shop (Mr. Rogers and Mr. Dingley’s premises were attached to the old Town Hall and assizes building in the town centre). The basket makers extended from Mr. Chings shop to the first door of the White Hart Hotel. The cow and calf market was held under Madford wall, cheap jacks were opposite the White Hart. The pig market was held at Star Cross at the Gable end of the Town Hall (Star Cross was the junction of Westgate Street and Broad Street).

The tolls of the market were let by public auction every Ladyday. The price would vary from £95 to £130. The town was much congested. There was no Exeter Road, Western Road and North Road. The former was made in 1824, the two latter in 1834. The butter and poultry market was held in High Street outside Harvey’s Bank (on the corner of High Street and Broad Street at what was known as Kneebone’s Corner). The butchers stood in the market at the following places with their names and their place of residence.

1 Benjamin Vosper New Shambles Ridgegrove

2 Richard Isbell New Shambles Ridgegrove

3 William Randle Newport Private House, High Street

4 Richard Randle Newport Old Shambles

5 Thomas Randle Southgate Old Shambles

6 John Parnell Fore Street Stall lease of market

7 William Tapson Church Street Old Shambles

8 Robert Cotton Westgate Old Shambles

9 John Sutton Northgate Old Shambles

10 William Essery Badash Old Shambles

11 John Box Tetcot Old Shambles

12 Thomas Hender Church Street Old Shambles

13 William Spear Milton Abbot Old Shambles

14 Richard Hain Broadwood New Shambles

15 Richard Chubb Lifton New Shambles

16 Digory Colwill Race Hill New Shambles

17 Henry Short Trevallet New Shambles

18 Thomas Bickle Milton Abbot New Shambles

19 John Vickery Broadwood Private Stall, Church Street

20 Thomas Stacey Dutson Private Stall, High Street

21 Richard Hain St. Thomas Private Stall, Church Street

22 William Pearse South Petherwin High Street

23 Richard Dingle North Hill High Street

24 William Ridgeman Tregadillet High Street

25 John Fitze Milton Abbot Church Street

26 William Stacey Dutson Church Street

27 John Reed Lewannick High Street

28 Mrs. Davey High Street New Shambles

29 John Reardon Egloskerry Lease of Market

30 John Kittow North Petherwin Lease of Market outside the Church

31 John Husband Lezant Old Butchers Market

32 William Kittow North Petherwin Lease of Market

33 Thomas Honey Occupied his own house Church Street

34 John Bear Tetcot Church Street

There was on average seven bullocks killed weekly. Mr. Benjamin Vosper slaughtered his at Ridgegrove, Mr. Richard Isbell at the Jubilee Inn stables. The others at the Bell Inn slaughter house, Back Lane (Tower Street). Mr. Vosper and Mr. Isbell were the only butchers in the market that sold a bullock to themselves, all the other butchers had only half a bullock between two. These were styled by the trade as beef butchers, to those that sold mutton, mutton butchers, and to those that sold pigs, pig butchers. Mr. Richard Randle, emigrated to America in 1830, left his wife and family at home in Newport. It was seen by the Conservative party of 1832 that every voter would be wanted. A special message was sent off for him and within a few days, before the poll was open, Mr. Randle returned and voted for the Duke’s nominee. He then remained at home and followed his trade in the market to the close of his life.

(The fiercely disputed Great Reform Bill, introduced by the Whigs, reforming the electoral system, was passed in 1832. Richard Randle was tenant to a property which had the right to a vote in Newport – hence the summons for the particularly bitter election in 1832).

Mr. Essery suppled the Duke’s house at Werrington, when the family were there. Mr William Atkins, the proprietor of the New Shambles entered an action against Mr. Chubb, his tenant, for using a crook that the former contended did not belong to him. It was tried at the Launceston assize and the Judge had it referred to arbitration. The decision by them was for each to pay their own costs. Mr. Amos Randle and his son John are the third and fourth generation that have constantly followed the butchers market during this century. Mr. Charles Vosper is the third generation who has constantly followed the butchers market during this period.

For the lighting of the markets a penny tallow candle was struck up to the joint of meat by a thin bit of scragging meat around it and a skiver run through it. The butcher’s custom was to dine at a public house, take a huge steak with them to be cooked. I have heard of an anecdote of the landlord of the London Inn (who was a very near and saving man) when a steak was frying for a customer, he said “Mr…. would you kindly allow me to dip my tattey (potato) in your gravy, it will do my tattey good, and your steak no harm.”

The butchers seldom cleared out from the market before eleven at night, and it would be often midnight before the doors would be closed on them. During this time very many robberies took place on their leaving the town. (The town had only 16 oil lamps burning.) Their carts would be robbed of their meats and other goods. That they had after those things had been so repeatedly done, one guarded the cart behind with a horn lantern to protect it. After this the corporation appointed six men to watch the town by night, two of a night. They had to give a call every half hour, “All is well,” and change their call twelve o’clock, “No row yet,” but this did not last long, for it was assumed that some of those men were in league with the marauders, for robberies continued and some of them on a huge scale. Mr. William Pearse of Newport House (now St. Josephs School) was broken into of a Sunday night and ransacked, and not long after, Mr. Charles Lethbridge’s house at St. Stephens shared the same fate. Then followed the Exeter Inn burglary in the early hours of a Sunday morning. My father told me that in his young days the fairs commenced at four the clock in the morning when the cattle in the winter was most sold by a lantern with a tallow candle by daylight, and that there was but two stalls in the market at that time. This must have been about the year of 1795, he was born in 1767, therefore he could very well remember this period.

There was room for the whole of the butchers to be accommodated in the two meat markets. The old shambles, inside and outside, was capable of accommodating twenty persons, and the new shambles about sixteen. The former would be closed of a Saturday night and not opened for cleaning until the Saturday following. It was very dilapidated and dirty. I don’t believe it had a coat of paint from the time it was erected to the time of its pulling down in 1840. The new shambles was kept much better, the landlord living on the spot. It’s not surprising that the butchers took stalls outside tradesmen’s houses. They rented their stalls from the latter from £5 to £6 per annum. In again referring to the old shambles it was built entirely of wood and to the best of my recollection there never had been any lime wash used for the interior. There was a Mr. Reardon of St. Stephens who kept a stall in the market, Broad Street, who sold hot teas and cakes. The water boiled by faggot wood and there the customers had to stand in the open to drink it. In the winter Mr. MacCollif supplied mutton pies by carrying through the market, having with him a two gallon kettle with a hot liquid, place a pie in a saucer and fill it from the kettle all for a penny. His cry was, “all hot, mutton pies, all hot, all hot, hot with the pepper and sweet with the salt.” These were the only places that the market people could get supplied, except when they went into an Inn and had hot gravy or toddy. There was no ordinary get up then by any of the innkeepers. I have seen many farmers and their wives buy a penny pie, cut it and dunk the soup, in the street on the market day.

It will be seen that the yearne market fell into disuse. The building was taken down in the jubilee year of 1810 and a public house was erected on the site (The Jubilee Inn which was constructed on the golden jubilee of George III (1740-1820)). If the old corporation had built a butchers market instead in this part of the town where the trade was then done and being the main thoroughfare of North Cornwall, what great improvements they could have effected in the place. The tolls that the market would have made then, but they slept and slept on as they had done in the centuries past, little thinking or caring for the wants of the greatest number, but allowed the butchers market to slide into private hands and also dispersed town lands, Scarne, Windmill, and Hay Common which has made a little return in its place. I leave the historian to deal with their public policy of the property which was placed in their hands at this time. When the present butchers market was built, the old butchers shambles, standing on the site of Mr. Hayman’s toy shop, it was first offered to the town council but they refused to buy it although one third of the price £300 was tendered by Mr. T. S. Eyre, Mr. Henry Greenaway and Mr. John George to be removed for the improvement of the two streets. I was not surprised at their refusal. For the council had not been purged of the old leaven, who had always shut their eyes to improvements. (The borough corporation before the Municipal Reform Act 1835 was a self-perpetuating group of aldermen and councillors who existed more for self-aggrandizement rather than for the good of the town, At elections they sold their votes to the highest bidder, usually to the lord of Werrington).

Bankers

Harvey’s Bank Broad Street Suspended payment in 1826

North Cornwall Bank Broad Street Suspended payment in 1822

There were three Banks in Launceston in the early part of this century, all of them in Broad Street, one to each corner of the Street. The Tamar Bank, the North Cornwall Bank, where now stands the East Cornwall Bank, and Harvey’s Bank, to the higher corner abutting High Street. (The Tamar Bank crashed in 1825).

Solicitors

Lethbridge, Son (John King) and Gurney Madford House

Mr. Parr Cunningham Hocken Westgate

Mr. John Darke Castle Street

Mr. Edward Spettigue Castle Street

Messrs Pearse and Lawrence Castle Street

Philip Row Blindhole

Mr. Charles Lethbridge had a nickname of ‘Turkey Legs,’ he was a tall slight man and small calf’s to his legs. He was commonly called by most of the lower people ‘Turkey Legs.’ A case came before him of calling names. He told the plaintiff that the boys called him out by his name ‘Turkey Legs,’ but he never took notice of it. He dismissed the case. Charles died at Madford in 1830.

Mr. Darke was engaged in the case of the men who broke into Robert Mule’s ‘New Inn,’ (Church Street) during the early hours of a Sunday morning, and drank and let the liquor run away. The case was tried at the Law Court, Town Hall. Mr. H. P. Lawrence joined Mr. Thomas Pearse’s firm in Castle Street in 1822 and lodged with Mr. J. B. Geake, a draper in High Street.

Ministers

Rev. John Rowe Minister of St. Mary Magdalene

Rev. Charles Lethbridge Minister of St. Thomas and St. Stephens

Rev. Mr. Cope Castle Street, Chapel

Mr. Cope left the town and Mr. John Bright succeeded him

Mr. Johnathon Eyre Baptist, Back Lane

Rev. John Rowe preached twice of a Sunday, morning and afternoon, seldom a service in the week. He had not many followers there as most of those that went to Church in the morning went to the Wesleyan Chapel or the Castle Street Chapel (erected in 1712) in the evening. Mr. Cope kept a grammar school in Castle Street (in what is now Lawrence House) and also constantly wnet week nights preaching in the villages. The Wesleyans were also well received, not only in the town but also in the villages. Mr. Johnathon Eyre preached Sunday evenings in the large room, Tapsons Court, Back Lane. There was an Act of Parliament to compel a man to marry a woman that got in to trouble through him, if he refused he was summoned before a magistrate and if he still refused, there would be a day appointed by the latter to be married and he was kept in custody until the Banns were called in the Church. He would then take there handcuffed and married. One of these cases occurred in Launceston in 1829, the other case at St. Stephens in 1833.

Doctors of Medicine

Messrs Pethwick and Pearse Westgate Street

Messrs Anderson and Brendon The Walk

Messrs Brendon and Patch The Walk

Messrs Brendon and Good High Street

These firms changed three times from 1825 to 1832

Dr. John Whittaker Westgate Street

Dr. Cory Rowe Dockacre

Mr. Pethwick served his apprenticeship with Mr. Ching, Broad Street. Dr. Anderson left the town in 1825. Mr. Peter Brendon was joined by Dr. Patch of Exeter. That gentleman when analyzing the contents of a stomach supposed to have been poisoned pricked his finger and died of blood poisoning in 1830. Dr. Good then joined Mr. Brendon. Dr. Whittaker painted a picture of the Castle, now in the museum. Dr. Rowe was a brother to the Rev. John Rowe and father of Sir William Rowe and Mrs Gurney, wife of Mr. Charles Gurney of the Madford offices.

Druggists

Thomas Ching and Son Broad Street

Thomas Symes Eyre High Street

William Hocken Behind the Town Hall

John Hurdon Church Street

Ching and Son were also wine and spirit merchants. Mr. Thomas Ching was very highly respected in the town and neighbourhood in the straight forward way that he conducted his business and also for his public duties, and also being kind and liberal to the poor and outcast. Mr. Hocken died in 1830. He was a Church and Sunday school teacher. Mr. Eyre commenced business in the town in 1826. Mr. Hurdon commenced business in the town in 1826, but left the town and went into business at Camelford in 1828.

Vetenary Surgeons

Walter Venner Castle Street

Charles Parsons Exeter Road

Mr. Bull Blindhole

Mr. Warne Raddall of South Petherwin served his apprenticeship with Mr. Venner .

Auctioneers

John Rowe Castle Street

Thomas Eyre Church Street

John Nottle St. Thomas Hill

Mr. John Rowe was one of the town sergeants. He was also a tailor by trade. Mr. Thomas Eyre emigrated to America in 1833. Mr. John Nottle was for some time a clerk at Madford.

Schoolmasters

William May Horwell School Newport

John Rogers St. Stephens Hill Newport

William Poulton Newport

Carried on his school in Back Lane, (Tower Street) in the old Wesleyan Chapel.

John Sleep Back Lane

Willliam Spear Old Town Hall Broad Street

Horwell School House was built in 1824. Mr. May was shortly after appointed master. He witnessed my indentures in 1827 to Thomas Eyre and Son, High Street. I was bound to them by my father to be a fellmonger. He had been in their employ for thirty four years. My apprenticeship commenced at ten years of age and did not expire before 21 years of age. The first year I was to receive 1s 6d. a week and to advance 1s each year, so at sixteen I should receive 6s a week and that would be stationary up to 21 years of age. My father died in 1829 and the business was given up. I then went into T.S. Eyre’s drug shop, remaining there for three years. I was then apprenticed by my mother to Robert Burt, shoemaker of Newport. Mr. Poulton’s school was carried on in the old Wesleyan Chapel in Back Lane (Tower Street). Mr. Spear was clerk at St. Mary’s Church, Launceston including the time when I was married, February 24th, 1840.

Wool Staplers or Fellmongers

Messrs John James and Thomas Langdon St. Stephens

Messrs William and Thomas Pearse Newport

Messrs Thomas and Arron Eyre High Street

Messrs Edward and John Marshall Newport

Mr. John Geake Southgate

Mr Jonathon High Street, removed to St. Thomas Bridge

The Messrs Langdon’s spinned their own sorted wool and also Mr. William and Thomas Pearse. Messrs Langdon’s wool stapling business was carried on in St. Stephens, their factories being at New Mills and Ridgegrove Mills. Mr. William Pearse and Son’s wool stapling was carried out at Newport; also the combing factories were at Wooda and Town Mills. Messrs Eyre and Son, Messrs Marshall and Son, Mr. Jonathon Eyre were wool staplers, as well as fellmongers. The latter trade was sheep skin pulling (or plucking) from the pelt or skin and then sorted in three heads, first, second and third. There was a custom in the trade, that apprentices should have sufficient lamb’s wool to make themselves three pairs of stockings , when knitted, a year during their apprenticeship. There were two women who regularly came to Launceston on a market day from North Petherwin and take home with them small buckets of wool and return it made into yarn fit for knitting stockings on the following Saturday. This was a custom that my parents adopted. My father was foreman to Messrs Thomas Eyre and Son for thirty four years and died in their service in 1829.

Spinning Factories

Messrs James, John and Thomas Langdon Factories at New Mills and Ridgegrove Mills

Mr. William and Thomas Pearse Factories at Town Mills and Wooda Lane

Mr. Richard Frost Factories at Town Mills and the Island at St. Thomas Bridge

Messrs Langdon’s business failed in 1826 so that their establishments were broken up. James with his family and John emigrated to America, Thomas not long after died at Newport. They were large employers. Mr. William and Thomas Pearse gave up the whole of their business in or about 1834. They were very large employers of labour, as their factories employed nearly two hundred hands. Mr. Frost employed a large number of hands at his two factories. He gave up business in 1825.

Tucking Mill or Serge Factory

Messrs Searle or Searle Brothers Town Mills

Searle brothers ceased working the serge mill in 1826, serge having been made at Newport for over 200 years.

Tanners

Treleaven and Son Newport

Thomas Honey Newport

James Snell Newport

Jonathon Eyre St. Thomas Bridge

John Close Near St. Thomas Bridge

Thomas Pode St. Stephens Hill

Thomas Harvey Westbridge

Marshall and Son St. Thomas Bridge

John Clare St. Stephens Hill

Walter Close St. Thomas

Mr. Treleaven’s sole leather, was kept in the pitts and for two years it was tanned from pure bark, the tanning for so long, closed up the pores of the skin so that it resisted the wet going through and it was made up article weather for boots and harness work. Mr. Thomas Pode tanned horse hide for making things and constantly followed Launceston’s markets to sell them. There was then a large sale for that type of article.

Tallow Chandlers

John Dymond Church Street

John George Broad Street

William Saunders Church Street

There was made for the use to meet the pocket of the working class at this time, a long eighteen, the latter number to the pound, and a candle of the same number to the pound, the rushlight, which gave little light but burnt for a long time. The latter was mostly used at the bedside of the sick by night.

Dairy Men

Samuel Holman Newport

John Pridham Westgate Street

William Thorn Behind the Town Hall

John Hill Back Lane (Tower Street)

Joseph Langdon Castle Street

John Holman Exeter Road

Shoe Makers

William Rogers Broad Street no child

Joseph Littlejohn Broad Street two sons

John Burt Fore Street three sons

John Heath Westgate two sons

Robert Welsh St. Thomas no child

John Bray St. Thomas three sons

William Short Fore Street three sons

William Bray Westgate no son

Harry Bray Castle Street one son

Richard Dingle Westgate one son

Thomas Harvey Harveys Lane three sons

Richard Cuper Back lane no son

Josh Martin St. Thomas four sons

Joseph Langdon Church Street no child

George Nevill Samford Timewells Lane two sons

John Williams Fore Street no son

John Cudlipp Back Lane two sons

John Martin St. Thomas Hill three sons

Joseph Goodman Newport one son

Thomas Yeon St. Stephens one son

(Harvey’s lane was one of the alleyways between Northgate Street and Tower Street)

It was the custom for tradesmen to bring their sons to their own trade. There are nineteen on the other side, five of them with no son. The other eleven had thirty three sons brought to the trade and there were several journeymen in the town that did likewise. John Burt was a town sergeant. Robert Welsh was caretaker at the Wesleyan Chapel; he died at an old age in 1825. His wife died on the same day. They were buried in the same grave in the Wesleyan cemetery. John William was nicknamed Jocky Williams. He was full of jokes and up to a lark, He borrowed a great coat of Mr. Perkin, draper, but not returning it, he saw him pass his shop, and called to him to remind him that he had not returned the coat. John put up a long face, saying that he was sorry he had not done so, but when he borrowed the coat, he was unaware that he had the itch. Mr. Perkin at once replied, “don’t you bring the coat to me!” William Short resided in one part of the old Workhouse in the Workhouse Road rent free (The old Workhouse is now Kensey Place, Dockacre Road). He was housed here due to having a large family. He carried on business as a shoe maker and attended the markets. There was also five other families who lived under the same condition, up to the time of the New Poor Law Act 1835, carrying on the business as a shoe maker for over half century. I have heard him state (William Short) that he never spent a penny to buy blacking in his life in which to clean the boots, but instead used as a substitute the back of the frying pan, which was then a common practice with the poor people. On another occasion he was walking down High Street, a country labourer he followed down the Street, he picked up an unmentionable, coming up to the man, he looked him sideways in the face and gaped. The man gaped also, he thrust it into his mouth and had to run to save a good thrashing.

There was an old saying ‘shoe makers Sunday.’ The men had seldom any work at their shop to do on that day. Working by piece, their work to begin was seldom ready before the Tuesday morning. This custom frequently had not only led to an idle day, but to a drunken one. Crispin day, the 24th of October, was the general custom to keep it up, in having a drinking bout in the evening that consequently led to a day or two’s fuddle for them. With not being able to get to work early in the week, and with these habits, the men had formed by this custom, they had to work late at the end of each week, and it often happened that it led into Sunday morning they would send out their work to the customer’s, whether in the town or country. I remember well a pair of boots sent to Mr. Gill’s wife on a Saturday morning that he sent them back again. Mr. Joseph Goodman was taken and sent to Bodmin Prison by Mr. Terleven, tanner, for debt. As soon has he was released, he emigrated to America with his family, but did not land in New York. But returned back on the same vessel (no steam then) and again established a business in Newport. Mr. Goodman and Mr. Thomas Yeon, although only one son each, did not bring them into their trade. I have omitted John Gregg, Church Street, from the list. He had an order to make a pair of ‘Hessian Boots’, he knew not how to cut them out, so he rode horseback to Plymouth to get instruction. The ‘Hessian Boot’ took its name from Hessie, the Blucher, worn in the Peninsular War by Bluchers army, the ‘Wellington Boot’, worn by Wellington at the same time, is why the name is given to the different boot.

(Hessian Boots took their name from Hesse in Germany and were knee high military boots with tassels, low heels, and pointed toes,)

Pig Dealers

Mr Lane Castle Street

Mr. William Symons and Son Northgate

Mr. James Lawrence Boyton

The above were the largest dealers in the trade. The first two were scouring the country, the first four days of the week to but for the Tavistock and Launceston market. Lawrence was sexton of Boyton and when attending the service in that Church one Sunday morning, he took a sleep and during the sermon he called out with a loud voice, “I say Raff Symons, you have not paid me for those Pig!” Symonds had the nickname of Raff.

Curriers

Penwarden and Son Star Cross

Mr. William Davey Back Lane

Mr. Richard Dingley Castle Dyke

Mr. Nicholas Burt Newport

Mr. Vaughan Ridgeman Newport

Mr. Burt and Mr. Ridgeman were the active agents in the Newport election in 1826.

Saddlers

Penwarden and Son Star Cross

Thomas Robbins High Street

James Deacon Behind the Town Hall

Thomas Honey Newport

Mr. Richard Penwarden was an Alderman and was very witty and a good comic. Mr. James Deacon was also a Sheriff’s officer.

Woolen Drapers

William Retallack Church Street

William Curgenven Church Street

John Perkyn Southgate Street

William Derry and Son Broad Street

John and Joseph Beard Geake High Street

Mr. Perkyn sold his business to Mr. John Nicholls in 1834. It is now carried on by his Thomas Nicholl, in the same place (5, Southgate Street).

Fruiters

Loveday Farthing Church Street

Mary Robbins Broad Street

Joanna Clark Southgate

Sophia Sleep Race Hill

Elizabeth Ball Fore Street

The above were all widows and most of them were left with large families of young children, and through their industry, brought up their families and were able to place their children out into the world in good positions.

Tailors

Joshua Farthing Church Street

John Perkyn Southgate Street

John Vascoe Angel Hill

William Medland Angel Hill

Richard Aunger senior Fore Street

Richard Aunger junior Westgate Street

John Ralph Southgate

John Packey Broad Street

John Dennis Behind the Town Hall

John Rowe Castle Street

John May Church

These men brought nearly all their sons to their trade. John Ralph and John Rowe were Town Sergeants. Joshua Farthing was a Constable. He was also a leader of the Cornish Militia and served with them in Ireland from 1811 to the summer of 1814. He was also a teacher of music and the first to own a piano in his house in Launceston.

Barbers

John Higgs Broad Street

He was the only barber in the town and had been from so for a very many years. He had five sons. He brought four of them to his trade.

Builders

William Burt Newport

Richard Wise Westgate Street

Ebsworthy Tapson Back Lane

William Tapson Southgate

John Holman Southgate

John Browning Castle Street

Thomas Hutchings St. Thomas Hill

William Matters St. Thomas Hill

Christopher Bounsall Newport

Mr. William Burt was the principle builder in the town. Most of the others were engaged in the town and country jobbing. William was a large employer in the area, and he built Tregeare House, and also Trelaske, the latter in 1823. He also built Mr. Ching’s house in Broad Street in 1829, the Horwell school house in 1824 and the construction of the Lanivet Water Works for the town. He was employed by most of the landowners in the district, his work being considered to be of the very best quality, and as for men, he had the pick of West of England, men such as Henry Burt, William Penharrel, John Stripling, Thomas Martin, William Martin and others equally good in the carpenters shop. For masonry, Thomas Thorn, Thomas Shilson, Henry Orell, Charles Browning, John Duckson, John Body, and others, but the wages were very low. The carpenters were not more than fourteen or fifteen shillings a week. The masons were about thirteen or fourteen shillings a week. The labourer received nine shillings a week.

Grocers

Mr Richard Dingley Broad Street

Mr. Edward Harvey Broad Street

Mr. William Nicholls Broad Street

Mr. Thomas Honey Southgate Street

Mr. John Doidge Broad Street

Mrs. Wilmot Hender St. Thomas

Mr. Dingley was the first appointed agent of the Tavistock Bank. He also carried on the business of watch making (the writer has seen him at work in his front shop window repairing watches). He also carried on the currying business. His workshops were in Castle Dyke and also the coal trade at Druxton Wharf. Mr. William Nicholl also ran a watch making business but gave it up after his father’s death. Mr. Dingley served his apprenticeship with the latter. Mr. John Doidge first went in to business in Broad Street, the house verified by the late Alderman Shearm, wine and spirit merchant.

Licensed Victuallers

Thomas Ching and Son, wine and spirit merchants Broad Street

Henry Greenaway, wine and spirit merchant High Street

Samuel Rowles Patterson, White Hart Broad Street

William Smith, Kings Arms Southgate Street

John Dyer, Launceston Arms Exeter Road

William Tapson, Dock Inn Race Hill and Exeter Road

Edward Pearce, Pack Horse Southgate

Jonas Copp, Westgate Inn Westgate

Samuel Symons, Cornish Inn Westgate Street

Harry Blake, Dolphin Westgate Street

Robert Acres, Exeter Inn High Street

John Philp, Little White Hart Star Cross

William Atkins, London Inn Church Street

John Tapson, Turks Head Church Street

Joseph Dunn, Bell Inn Tower Street

Charles Atkins, Ring O Bells Fore Street

William Masters, Jubilee Inn Fore Street

John Jory, New Inn (1850 Market House Inn) Church Street

William Burt, White Horse Newport

Robert Burt, Northumberland Arms St. Stephens

John Burt, Fifteen Balls (13 Duke Street) St. Stephens

Ching and Son were Aldermen of the town and served as Mayor on two or three occasions. Their house in Broad Street was where the Judges lodged during the assizes. John Dyer’s only son, John, 21, was thrown from his horse and killed in Exeter Road in 1829. William Tapson was a Constable present when Jory was shot and killed at Bamham in 1814. Henry Blake or Harry Blake was the driver of the night mail to Falmouth. Robert Acres was one of the biggest men in the town, he weighed over 25 stone. His coffin had to be turned on one side to bring him through the Exeter Inn passage. The Exeter Inn was the most popular of any house in the town, it was the resort of the old Corporation and the tradesmen of the place. Mr. John Philp was thrown from his horse and killed. Mr. Dunn was a large local brewer and had the nickname of ‘Whitbread’ due to this. Charles Atkins was one of those that captured the two men, John Joice and John Williams, who had broken into the Post Office in 1805 and who were executed at Bodmin. Mr. William Burt had two brothers killed, John in the falling in of the arch of the reservoir at Lanivet Green, and Nicholls in repairing the well head at Werrington Park, a flat stone fell on him and he was crushed to death.

Beer House Keepers

Thomas Yeon St. Stephens

William Coombe Westgate

William Bray Chapel

John Higgs High Street

Thomas Colwill Race Hill

William Dymond Angel Hill

George Scown Fore Street

Thomas Pote Back Lane

Richard Cuper Back Lane

William Matters St. Thomas Hill

George Clark Castle Street

William Clark Southgate

William Scown Bowling Green, now the cemetery

Cuper, Clark, Clark, and Scown were licensed to sell tin cider only.

Bakers

John White (1784-1853) Southgate Street

Mr. John White was the first to establish the baking and confectionary business in the town. Nearly every housekeeper made their own bread and sent it to the common oven to be baked. There were but few houses that had stoves in them, so the joints of meat and all heavy baking had to be taken to the common bake house. It was uncommon for the working classes to have a grate in their houses let alone a stove. Their fire was on the heath and faggot wood was their principle fuel for burning. The common oven was lit with furze.

Common Bake Houses

William Dingle Northgate

John Prout Castle Dyke

Charles Body Westgate

Joshua Whitham Madford Wall

Elizabeth Uren Southgate

William Short Fore Street

Richard Dingle Northgate Street

Bake Houses

Hugh Green St. Thomas

Thomas Phillips Newport and two common bake houses in the village of St. Stephens

Distress in Agriculture

I well remember that farmers were constantly sending petitions to Parliament to enquire in to agricultural distress, and also what remedy could be suggested for the employment of their superfluous labour population. I have heard from Mr. John Lang, uncle of the Messrs Lobb’s of Lawhitton, whom his father and himself rented the Barton in that parish, say that at a vestry meeting the labourer would be put up for auction and would be knocked down to the highest bidder, commencing at seven pence a day, advancing a penny a bid, seldom a bid wnet higher than eleven pence. He was then knocked down to the buyer, the parish making up the deficiency for his wages to sixteen pence a day.

Corn Market

The corn market was held in the crown court of the Guild Hall (in the Town Centre). Very few of the large or better to do farmers brought their corn to the Launceston market, instead taking their produce to Tavistock market where there was found to be a better price achieved. It was the small farmer who brought his grain into the Launceston market. Seldom would one bring more than two bags into the market, often just the one. This he would bring in on horseback, himself riding on it. The buyers were Grist Millers, Mechanics and the labourer. Two of the latter would club together and purchase a bag of wheat and handed it over to the Grist Miller to be ground with only the bran taken out.

Watch Makers

Nathaniel Spry Southgate Street

William Reynolds Westgate Street

Richard Dingley Broad Street

William Nicholls Broad Street

John Box Broad Street

James Uglow St. Thomas

Mr. Dingley also carried out on the business of a grocer and currier, the latter in Castle Dyke. He was appointed agent to the Tavistock Bank in 1829. Mr. William Nicholls also carried on the business of a grocer as did Mr. John Box.

Printers and Stationers

Thomas Eyre Church Street

Theodore and William Roe Bray Westgate Street

Haberdashers

Thomas Eyre High Street

William Martin Church Street

Mr. Thomas Eyre was also an auctioneer. He emigrated to America in April 833, taking out with him two of Mr. Benjamin Vosper’s sons. The latter made good positions out there with one of them, Thomas Holman, becoming a tradesman in New York. Mr Eyre sold his business to Mr. Cater of Huntingdon, the son, William Cater, who now runs the business.

Painters

William Gregory Southgate Street

George Vivian Westgate Street

Painters were but very little in demand at this time. For on an average there were not five per cent of the houses painted in thirty years and some of them had never been painted at all. From the time that they were built, 200 years ago, not even up to this time. Take some of them in Angel Hill, the alleys in Fore Street (Northgate Street) and other places. A little lime wash was applied here and there at Lady Day (the feast of the annunciation, 25th March), before the summer assizes.

Coopers and Panner Makers

John Ashton Northgate

Peter Westlake Southgate

John Congdon Newport

I well remember Mr. Ashton’s shop. He was the owner of the property between the Northgate Inn and the Northgate. He had of a Saturday a large show of panners laid outside his shop as well as dung butts. Dressing was carried on horseback on the farm as the parish and farm roads were so bad that carts in some places could not be used.

Pattern Makers

John Rowe and Son Fore Street

William Castine (1770-1839) Church Street

Patterns were worn by all the females in town and country, and in the winter to Church and Chapel. On the North entrance and West entrance to St. Mary’s Church were painted in gold letters on the door of the Church ‘be pleased to take of your patterns.’ The latter remained on the doors up to the restoration of the Church in 1857. John Rowe and Son attended the North Cornwall fairs, and did a large trade in patterns and clogs.

Dyers

William Bounsall St. Thomas

Robert Holman Southgate

Glaziers and Tin Men

William Thorn Behind the Town Hall

John Edgcombe The Walk

Harry Jewell Castle Street

John Bolt Fore Street

Ironmongers

Prockter and Son Southgate Street

Castine and Son Church Street

Westlake and Son St. Thomas Hill

Thorn and Son Behind the Town Hall

Dymond and Son Near the Tower

Mr. Castine was also a pattern maker.

Wire Workers

Robert Watling Westgate

Robert Watling was elected Mayor of the pig market in 1827.

Hatters

James Treleaven and Son Fore Street, removed to Broad Street

Mr. Thomas Rice Fore Street, removed to Broad Street

Smale and Rowe Church Street

Abraham Sheppard Broad Street

George Farthing Wood Road

George Farthing was an uncle to my wife, Mary Farthing, who now lies in the cemetery under the Walk. The hatting industry was one of the most important in the town. There were over thirty men and also several apprentices employed in this branch of industry, with Treleaven and Son by far the largest employer. The hatters supplied to most of the towns North and South of Launceston, with Treleaven and Son also going East so far as Okehampton, and most of them attended all the fairs in the district. For the men there was a trades union, and the hatters wages were better than any other trade, but they freely indulged in drink with the Bell Inn was the headquarters. This was due to having to work over a steam furnace.

Blacksmiths

Thomas Stapleton St. Stephens

William Langdon St. Thomas

John Gilbert Castle Dyke

Angwin and Son Westgate Street

John Jennings Back Lane

Thomas Prout and Son Back Lane

Thomas Saltern Bottom of Angel Hill

Samuel Poulton Back Lane

The old fashioned way was for blacksmiths to take a measurement was by way of a piece of string. William Angwin and Son were also White and Lock Smiths. Their principle business was in the making of kitchen ranges. Stoves were but little in use, for nearly all householders sent their baking to the common oven, and the upper class had an oven in the house. It was earthenware one, heated with wood or furze.

Letting Horse, to hire

William Fry and Son Race Hill

William Dyer Exeter Road

John Palmer Blindhole

James Shilson Westgate

Mr. Fry junior (only son) was thrown from his horse at Pages Cross on his way home from Tavistock market and killed in 1831. William Dyer’s son (only son) was thrown from his horse in Exeter Road and broke his neck in 1829.

Ropers

Valentine Pose (Pode) Westgate Street

William Grylls Back Lane

Richard Heath Westgate Street

The roping trade paid very low wages. The men were paid nine shillings a week. The youths were paid two shillings a week. The ropers attended all fairs in the district and Launceston market. Two (of the above) had seven sons, one had none, and they were all brought up to the trade.

Basket Makers

William Coombe St. Thomas Bridge

Richard Ham St. Thomas Hill

James Shilson Westgate Street

George Timewell Church Street

Thomas Dawe Workshop at St. Thomas, resident in Back Lane

Millers

William Madgwick Bamham Mills

John Jury Yeolmbridge Mills

William Bailey Ridgegrove Mills

Abel Uglow Town Mills

Wilmot Hender Town Mills

Launceston was a great centre for the farmers in North Cornwall to sell their wheat for they could always meet with a ready sale. All the named (above) did a large trade. The first four men sent large quantities of flour to Plymouth. Wilmot Hender supplied nearly all the flour shops in the town. Mr. John Phillips of St. Thomas was her manager. It was currently reported that Mrs. Hender bought 150 bags of wheat. I have heard Mr. Phillips say that North Cornwall red wheat was not to be surpassed for its quality. This was a very important industry in the neighbourhood, for it brought to the market a large number of farmers.

Malsters

George King Mann Race Hill Malthouse

Daniel Shilson Angel Hill Malthouse

John Gard Bounsalls Lane Malthouse

Henry Greenaway Castle Dyke and Wood Lane

William Perkyn Castle Dyke Malthouse

William Hooper St. Stephens

Samson Bennet Yeolmbridge

Malsters were as large buyers of barley as the millers were of wheat. Large quantities of barley was malted and sent to Plymouth and at this time every publican brewed his own beer as also did many private persons. When the latter gave you a glass of ale they would tell you, this is our own brewing, it is the pure malt and hop.

Weavers

William O’Brien St. Stephens Hill

Thomas Dawe Fore Street, Ram Alley

The looms worked by Mr. O’Brien and Mr. Dawe were, so well as I can remember, six feet long and also that in height. The latter was worked by Mrs. Dawe. These were the last machines of the sort in the town. Mr. O’Brien came from the North of England and settled at St. Stephens when a young man. He continued in this work up to a few weeks of his death at an old age in 1834.

Worsted and Yarn Spinners

Two women from North Petherwin followed Launceston market weekly to take back wool to spin for knitting stockings. I have had stockings knitted for the wool they have spun. Mr father was in the wool trade and I have heard him say that there was scarcely a country cottage without a machine for this purpose. When an apprentice to Mr. Spettigue in the latter part of the last century, he has taken horses laden with wool to Chapmans Well for the cottagers there to spin. For his master, the yarn market and a number of villagers from the country brought their yarn to the weekly market. I have no idea when the first introduction of spinning factories were first introduced to the town, but on a pane of glass in the Bone Mill on the second floor (formerly a spinning factory) is cut out the date that the factory was worked in 1803. After the latter’s introduction the yarn market declined and on the jubilee of George III in 1810 it was pulled down and the Jubilee buildings were erected in its place.

Nursery and Seedsmen

William Spry Southgate

Mr. Spry had two nurseries, one at Clampits (near the hospital), and the other at St. John running up to the Pennygillam Gate. He employed a large number of men and his principle culture was to grow shrubs and trees.

Buff Breeches, Gaiter, Overall Maker

Samford Timewell Church Street

In Mr. Timewell’s day buff breeches were worn by the Squire, Yeoman and well to do farmers and also in the hunting field. Gaiter’s and overalls were made to match and buff gloves were generally worn.

Turners in Ivory, bone and Wood

John Maunder Church Street

Mr. Maunder was a dealer in old curiosities. He regularly followed the markets and the fairs of the North and West of the town.

Cabinet Workers

Thomas Geake High Street

John Jenkin Broad Street, removed to Church Street

Mr. Thomas Geake’s cabinet work was assumed to be the best in the county. He carried on a successful trade for many years and was held in high esteem by his fellow men. I have in my possession a mahogany chest of drawers made by him for my father-in-law, Joshua Farthing, in 1805. They are as trim and good as when they came out of the maker’s hands.

Wheelwrights

William Edgecombe Southgate

John Dew St. Stephens

There was but few if any carriages kept by anyone in the town. I can only remember but one gig kept in the town. Anyone that had any distance from home had to ride on horseback as no vehicles could travel on the parish roads for they were seldom or even repaired. When Mr. Bucknel came to Tredidon he was unable to drive to Launceston. Deep ruts made in the roads by dung butts, meant that any gig or carriage went down to their axles. Mr. Bucknel then tried the ‘Way Warden,’ Mr. Abel Uglow, of St. Thomas with an action. The latter called a vestry meeting and persuaded them to put the roads in good condition. At this time the horse traffic had to go through the river from St. Thomas bridge to the Church and then through the leat to Town Mills. All parish roads were then no better. Horses had to take the dressing for the fields in butts, one each side, and when the farmer and his wife went to market or Church, they rode on horseback.

It must be noticed that what had been the staple trade for centuries of the town up to 1830 had all but disappeared, and in a very few years after there was scarcely a remnant of it left. Fell mongering, wool stapling, serge making, weaving, yarn spinning and with many other trades of local manufacture such as hatting, candle making, dyeing, thong making, coopering, pattern making, and panner making, not one of these trades remain. Then take ropers, blacksmiths, and shoemakers when there is but one of each now, back then six were employed during this period. The assizes were held here annually and the town was on the High Road from London to Falmouth where all goods and despatches from the continent came in and passed through. The manganese mines were also in full work.

Carriers

Russell’s wagons for goods, rested in the town on their way from London every Saturday at noon, on their way to Falmouth. If a parcel or package came by them, a letter would have to be posted the Wednesday week before. Their wagons were due in Launceston Sunday’s midday and when one of their wagons was loaded with gold bars, there were eight horses, two drivers, and two guards, one each side, dressed in white smocks with each carrying a fire arm. The bullion was taken to the Bank of England. Their offices and stabling was at Westgate, with Mr. Lake their manager. Mr. William Davies’s four horse wagon started from the top of Fore Street (Northgate Street) at 6 a.m. for goods and passengers for Exeter each Monday, resting the night at Sticklepath (Cornish Arms), arriving at Exeter the following day at 2 p.m.. It left Exeter on the following day at noon, again resting for the night at Sticklepath, returning to Launceston on the Thursday at or about 3 p.m.. He had also a light one horse wagon that left the town with goods and passengers, at 9 a.m. Wednesday, resting the night at Sticklepath, arriving at Exeter at 1 p.m. on the Thursday, leaving the latter place on the Friday at noon, resting again for the night in Sticklepath, arriving back in Launceston at 2 p.m. on Saturday. The fares for passengers were 3/6. Mr. Athanansus Broad, a wagoner, went to Plymouth three times a week. Heavy goods were charged 1/6 for a hundred weight. Mr. Anthony Carwithen and Mr. John Painter’s light wagons for Plymouth, with goods and passengers, leaving Southgate at 8 A.M., arriving in Plymouth at 7 p.m. It returned on the following day at 7 p.m.. The passengers fare was 2/6. They also took letters with them. There charge was two pence, there was abit of string tied around each letter, so that it should appear to be a light parcel. The reason for this was to defeat the Revenue Officer. If any letters from the town was conveyed over to another carrier, say Dartmouth carrier, there would be an extra two pence, which made four pence. This is the way I received my letters when in Dartmouth in the winter of 1839. The charge for a Post letter to there was nine pence, so it was a saving of five pence, but I seldom got my letter until four or five days after it had been sent. John Pengelly came once a week from Truro to Launceston with one horse spring-loaded cart, leaving Truro Mondays, resting the night at Bodmin, arriving in Launceston at 4 p.m., Tuesday. Leaving again on the following morning at 11 a.m. and resting again for the night at Bodmin, finally arriving back in Truro on the Thursday afternoon. Fares for passengers 2/- to Bodmin and 3/6 to Truro. There was Mr. Oliver Davey’s and Mr. Avery’s wagons, from Bude and Boscastle but they were principally used for conveying coals to the town in the winter, and in the summer for bringing heavy goods to the town, which had been landed at these ports from Bristol.

Coaches

There were two Royal Mail coaches with four horses and a guard. The down mail arrived at the White Hart at 11 p.m. The up mail from Falmouth at 3 a.m. They were licensed to carry ten passengers, four inside and six outside. The guard wore a scarlet livery and carried a blunderbuss. There were two day coaches from Falmouth and Exeter, the latter arriving at the town at 1 p.m. with the Falmouth coach about half an hour later. Both these coaches were again driven by four horses. The fare through was 16/- from Launceston to Exeter, 12/- from Exter to Launceston, and 14/- from Launceston to Falmouth. There was no coach to Plymouth although a run was set up in 1833 driven by three horses but it proved to be uneconomical and the service was soon withdrawn. I have frequently seen it come down Race Hill with but one or two passengers in the top. The Tamar Terrace Road had not been cut at this time. (Tavistock Road as we know it today, was only cut in 1835). It was the custom of noblemen and gentlemen in the county to drive their own coaches when they went to London, driven from the box seat if posted, with two post boys riding dressed in white breeches and scarlet coats. (Pots horses were kept in inns on the major coach roads for use by the mail coaches or rented to travelers.) I was with Mr, Thomas Eyre, the chemist, in 1830, and his brother Arron, who came from Werrington, wrote to him from Plymouth saying that he wanted to pay a visit to Launceston to see his brother, but was unable to due to there being no conveyance from Plymouth to Launceston, but a three horse coach ran to Tavistock enabling him to get that far. I was sent on horseback to Tavistock to fetch him and I rode back on the same horse behind him.

Post Office

There was not then any country post men. If a letter for the country district arrived it was placed in the post office window and if a neighbour should chance to see it, he or she was allowed to take it by payment of the postage. Postage for a letter from Launceston to Liverpool was 1/3, to London 11d., Tavistock 6d., Plymouth 7d., Exeter 6d., Dartmouth 9d., Bodmin 6d. Letters could be sent through the post office with or without payment, if the latter preferred to be paid for at the point of delivery. The Lifton and Lewdown mail bags were taken by hand and all their post came via Launceston post office. The postman started with the mail bags at half past five in the morning arriving at Lewdown at eight a.m. He returned to Launceston at six p.m. When I was an apprentice I took the Sunday post there for several years. The north Devon mail was brought here from Holsworthy on horseback, arriving in the town at ten ‘o’clock in the evening. The Plymouth mail was brought to Launceston by mail cart also arriving at ten o’clock in the evening. The mail cart returned to Plymouth after the arrival of the Falmouth mail cart at three o’clock in the morning. I have seen all the post delivery of a morning, taken by the postman, Hugh Isaacs, grandfather of Thomas Cavey, the old Laneast postman, bringing out the letters and holding all of them in his left hand. There was just the one delivery each day. The practice of commercial travelers was to post just the one letter to one of his customers informing them when he should be calling on them and he would then ask that the customer inform the other customers of this date.

Water Supply before the Lanivet Green Supply in 1825

For the water supply there were eight town pumps; one at the top of Race Hill, Shepherds Well, Madford Wall Well, Westgate Well, Westgate Street, Bounsalls Lane, Broad Street (this was called the flogging well) and in the Walk. There were three conduits; Race Hill, which was supplied by a small reservoir under Madford by the side of the hill, one abutting the London Inn in Church Street, and another in Fore Street close to the Jubilee Inn, both with slate tanks. The former was supplied from the reservoir in Race Hill, the latter from the Broad Street reservoir which was supplied from an adit in Bounsalls Lane. In the summer there was but little water to be had. Water was in the summer fetched from Northgate Quarry Well, the River and Shute at Newport. The latter was the favorite place for the publicans to brew with. There was a good stream of water from Chapel to the Northgate, running through Miss Pearse’s garden in earthenware pipes and passing through a shute in a large granite trough close to the old Northgate. The principle supply for the Northgate area was from the Quarry Well. Charles Ruse of Quarry Lane cleaned out this well every summer and also superintended, keeping it under lock and key. He charged each inhabitant of the area a penny per householder.

The Lanivet Green Water was brought in to the town, but the hamlet received no benefit from it whatever. When the works were completed in 1825, the supply of water was little better in the summer months than before it had been completed, for the old sources had been neglected. The constant supply of water from the shute feeding in from Chapel had been allowed to fall into disrepair with some being diverted into another channel. There were five water taps, fixed in different parts of the town for the distribution of the water from Lanivet Green. One on the Southgate, where carved into the granite are the initials of the Mayor at that time Parr Cunningham Hocken, and the date. The others were on the Castle Wall, Castle Dyke, North Road, the Old Butchers Shambles facing the Church, another in Back Lane (Tower Street) near the Bell Inn, and another at the bottom of Fore Street (Northgate Street) by the Congregational Chapel. But as has been previously stated, this water supply was not enough to feed the town during the dry summer months, so the Mayor had to continue the annual custom of padlocking all the pumps and water taps from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. Many women would take their pitchers to the pumps and water taps in their night dresses at 3 a.m. and leave them. The rule was, first come, first served and when the Town Sergeant arrived to unlock the pumps and taps, there would be a large crowd of women and girls waiting, and the cry would go up as to who was first and seldom did they part in peace with squabble’s breaking out with broken pitchers and a trial of strength of who had the strongest hair. It was a very old saying, when everyone had to take their baking at the common oven and fetch their water pitchers, that the conduits and the bake house were the two schools for gossip and scandal.

Sanitation

Sanitation at this time was in a deplorable condition especially for a borough town which could boast of nearly 600 inhabitants. In Fore Street (Northgate Street) there was a gutter of over three feet wide in the middle of the street carrying the town sewage into a sewer that conveyed it to the Northgate shute where it joined stream that ran into the large pond in the Deer Park, now Miss Pearse’s garden. It then flowed into the open and crossing Wooda Lane in an open gutter emptying itself onto the Priory Meadow. The inhabitants of Fore Street threw all their night soil, slops and refuse into this open sewer.

At the top of Fore Street in front of the Jubilee Inn, there the street sweepings of that part of the town were kept, and again all the nearby residents would empty their night soil, slops and refuse unto this heap which included around not more than thirty families that resided in the housing where the Wesleyan Chapel now sits. In Broad Street, the sweepings were kept close to the Town Hall near the clock, and again all the night soil, slops and refuse were thrown on this heap. The town dung was taken away twice a week, Mondays and Fridays. In Blindhole there was a large pond, or catch pit for town sewage. It emptied into an Orchard just below Dockacre, it having passed through an open gutter in Ridgegrove Hill close to Dockacre House. In Castle Dyke there was an open privy with an open catch pit adjoining where the area’s residents threw all their waste. The Castle Dyke was a place where every kind of dirt and filth was thrown and it was left to the residents, who had back entrances, to clean it. But this was seldom carried out, unless there were plenty of scrapings about and the place became almost impassable as nearly every building had a dung heap at their back door, claiming their right to the soil. The town scavenger never interfered with them and never put his broom over it. Before the Castle’s retaining was built, there were stables and pig sties on that side of the road.

Angel Hill and Race Hill were no better, nearly all of them had to throw their night soil out into the open street. Samford Timwell’s Lane was made a public urinal, where not only male but female passers-by would relieve themselves. In the alleyway, there was scarcely room for two to walk abreast and along there lived several families, with also some back entrances for those that lived in Church Street, and of a Saturday, a market day, the sight of females and children passing there was not only objectionable, but disgraceful! Tapsons Court, in the middle of the Court, was another kept another dung heap where all the residents threw their night soil, slops and refuse, and I am led to believe that the landlord at that time made his claim for it and removed it when he thought a fit time to do so. There was an open privy at the bottom of the Walk, over an open sewer that emptied itself into the Orchard below Horse Lane (Dockacre Road), and another open privy in the corner on the Walk of the old grammar school, close to the cottage. There was also an open privy in Blindhole over the town sewer. The pond that the latter ran into and the privy were not more than fifty feet from the entrance of the alderman John Roe’s principle entrance to his house, and not thirty feet from the entrance of Mr. Bull’s house, part of the site of the butchers market. There was also an open privy over the town sewer in the Dockey, but this was out of the way of all town dwellers. In Church Street, many of the residents had no back entrances so they emptied all their waste to the grating opposite the water tap of the London Inn. Many of the houses of the better class had privvy’s with a catch pit. This was cleaned out once every six months after those residents had gone to bed and many of those privvy’s were in houses that had no backlet (rear court) or not so large as a man’s hand. I have been informed that the privy at the old Ring O Bells was so deep that it was never cleaned out.

Recovery of Small Debts

For the recovery of small debts there were two courts held annually in Cornwall on an alternate six month basis, one at Truro and the other at Penzance. The limit of debt I believe (but I cannot state accurately the sum), was five pounds and under. You had to apply to the Registrar of the respective court and he would grant a summons through the Sheriffs Officer to where the plaintiff and defendant would have to appear, so the plaintiff would have to go to either Truro or Penzance as the case might be. The plaintiff, to recover a debt of a few shillings, would have to travel to at least Truro, and if the coach was used the fare was 14 shillings to get there with another 14 shillings to return. If he went by the Truro carrier the fare was 3s. 6d. but he or she would have to sleep the night in Bodmin and do the same on the return journey. The only other option was to walk.

Sports

Cock Fighting

Cock-fighting was a very popular with all classes, with the upper classes having a Cockpit at Badash Farm, whilst the working classes held theirs at either a Public house, the Castle Green (where there was a ring), or up on the Windmill. The first and last Cock fight I attended was in the spring of 1834 at the Lent assizes. I had saved a little pocket money to spend at the assizes and was induced by others to see the Cock fight. I went and lost all my savings! I became a wiser but sadder youth and I never attended another cock fight, and soon after it went out of fashion.

Badger Baiting

Badger baiting was a sport that took place at Christmas, Easter, and Whitsuntide on the Castle Green, the Windmill and at St. Thomas Church yard before that part near the river was consecrated.

Skittle playing

Skittles took place all year round but more frequently in the summer months. This game was principally played at a public house and most of them had a skittle alley and those that didn’t a temporary alley would be made up in the public road. This was the case with the Packhorse Inn (on the corner of Southgate Place and Madford Lane once the Hardware Centre) at Whitsuntide. The skittles would be built between the three roads, Exeter Road, Race Hill and Southgate Street. This game was also played on the club day, Whit Monday, at the White Horse Inn. Card playing was another popular pass time in the public houses with many games being played throughout the night, at this time public houses could stay open all night.

Pugilism

Fighting was a very popular pastime with the blistered hands, unshorn chins and fustian jackets. There was scarcely a summer evening that passed without a match being organized on either the Windmill or the Castle Green, with the latter being the most popular. The originators of these sports were blacksmiths, shoe-makers, and tailors, and principally those engaged in indoor pursuits. There was seldom a Saturday night that passed without a fight between the country men and the town’s men. There was also great rivalry between Launceston men and St. Stephens men with the latter often throwing their lot in with the country men, and these fights often originated from a public house brawl. At the Conformation (held every seven years to enter new entrants into the ministry by the Bishop of Exeter) a large number of people would gather in the town from between twenty and thirty parishes. At the Conformation in the summer of 1827 a squabble broke out outside St. Mary’s Church between two men. The cry was to go to the Castle Green to fight it out, which they did and whilst their fight was taking place, two further battles broke out, with three fights going on at the same time. Prize matches would often be organized taking place on the Windmill or in the old Priory Field. If the former was chosen, the fight would be held on the Market day to make it more popular, but if the Priory field was chosen, it would start at 6 a.m.

Wrestling

Wrestling was a popular past time especially with the miners in the West of Cornwall, but after the great wrestling match between Cornwall and Devon at Plymouth in 1826, it also became quite popular in Devon. In the spring of 1826 a challenge was made by Devon to the Cornish for their respective champions to meet with a prize of 200 sovereigns going to the winner. The Devonshire champion was Abraham Cann and the Cornish champion was William Polkinhorne of St. Columb. The match took place in July 1826 at Plymouth and one of the rules drawn up was that the champion should be led off the ground by his second. Polkinhorne threw his man amidst great excitement and the Cornishmen rushed and screamed from their seats and carried away their champion in great triumph. The rules had been broken and the stakes were never paid over to the winner. This match caused quite a lot of excitement throughout Cornwall, and also not least in Launceston. There was a print displayed in Mr. William Dymond of Southgate Stationers window announcing the details of the match. Such was the excitement that some of the towns men decided to form their own club with the aim of a tournament taking place the following summer. This took place in a hooded ring erected in a field on the left hand side of Park Gate at St. Stephens, but the subscriptions fell short and the whole affair turned into a fiasco, resulting in a heavy loss for the promoters. This was the first and last wrestling Guild in the town.

Horse Racing