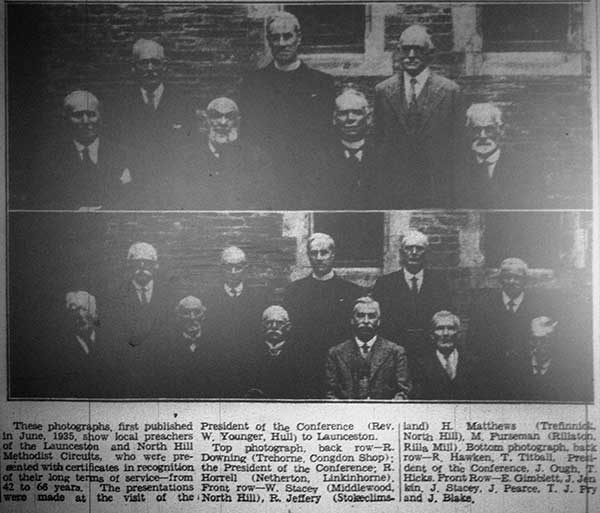

.

John Wesley visited Launceston on no fewer than 32 occasions, with his first visit on the 22nd October, 1743, when he rode direct from Sticklepath in one day. He remarked on this visit “one stopped me in the street and asked abruptly ‘Is not thy name John Wesley?’ Immediately two or three more came up and told me I must stop there. I did so, and before we had spoken many words our souls took acquaintance with each other. I found they were called Quakers, but that hurt not me, seeing the love of God was in their hearts.” On this occasion, he appears to have passed through without preaching. His first sermons in the borough being preached in an open-air service on St. Stephens Downs on 29th August 1747 having preached the previous Sunday at Week St. Mary, St. Gennys, Tamerton, Tresmeer and Laneast. He again preached on St. Stephens Down in August 1750, but it was the following year that he first preached in the town was in a room of a house that stood on the site of Symons Jewellers shop in Church street by Sandford Timewell’s Lane, the adjoining passage leading to Castle Dyke.

For this meeting, Wesley had ridden with his wife from Tamerton, and he was met in the town by what was described an unruly mob, it being a market day, and was severely hustled on his way to the room, and even had missiles thrown at him. On the following day (Sunday) he preached in the main street to what he afterwards spoke of as “a large concourse of persons.” He again faced hostility and was attacked by a mob of boys and gentlemen on the other side of the street, and, finding discretion the better part of valour, Wesley finished his service back in the preaching room, hastening afterwards to Tresmeer, where he was friendly with the incumbent vicar, the Rev. Charles Beresford.

Methodism did not take root easily in the town, for when in July 1753 Wesley met with the stewards of the newly formed society, they remarked that ‘things did not seem so hopeful as they might have been.’ Undaunted, Wesley addressed “a wild yet civil congregation” in the Town Hall. However, in 1755 he wrote that he had found things very much more encouraging, where Wesley entered in his journal that on 18th September 1755 that he preached in a gentleman’s dining room, capable of containing some hundreds of people.” This implied that it was within the town but it was likely to have been outside possibly Tregeare.

One of the oldest Methodist class tickets known to exist originated from Launceston. It was presented by John Wesley himself to Mary Bounsall in 1760 and is now preserved in the Methodist Archives in London.

He was very dismissive of ‘culpable apathy’ of the clergy of the Church of England. So much so that when on a visit to Launceston in 1758, in a letter to a friend, he described the clergymen of Launceston and Plymouth Dock as men who ‘neither know, live, nor teach the Gospel.’

Before a chapel or even a room was opened, it seems John Wesley, as noted, preached in the house which stood in Church street (this house was destroyed by fire in 1845). Between Wesley’s visits to Launceston in 1775 and 1789 a piece of ground was bought in Back Lane (now Tower Street which was situated between the old Tower street chapel and the Passmore Edwards Library, but on the opposite side of the road.), upon which was erected what was then called ‘a new meeting room,’ ‘meetingers’ being the opprobrious term, besides ‘Methodists,’ which was hurled at the new sect. The trustees of this early church were James Palmer, John Bray, Henry Essery, John Clode Hender, Richard Williams, William Pearce, and John Paul. Wesley preached at this ‘new’ meeting room on September 28th, 1790 where he found a strong congregation. In 1795 Launceston became the head of the circuit with its limits reaching from Launceston to North Hill, Kilkhampton, Holsworthy, Okehampton, Callington, Tavistock, Gunnislake and Looe.

By 1797 the cause in Launceston had increased in its popularity the small meeting room had to be enlarged by the purchase of a piece of ground adjoining, and two new trustees were added, Jerimiah Davey and Nicolas Burt. At this time the number of resident ministers was three; at the formation of the circuit, there were only two. In 1809 the various stations became so large that the number was increased to four. It was not long before Tavistock, including Okehampton and Liskeard, including Callington and Looe, formed their own circuits, and in 1815 Holsworthy and Kilkhampton followed suit.

In 1838 several of the members, dissatisfied with the attitude of their ministers on matters of church government, broke away and started a new cause for themselves, worshipping for some time in the Western Subscription Rooms (now the Cornish and Devon Post offices) and after their numbers increased, they built the new United Methodist Chapel on St. Thomas Road.

The chapel in Back Lane was sold to Joseph Strike in 1866, he took the building down and erected three cottages on the site, and these remained there until the 1960’s general clearance scheme.

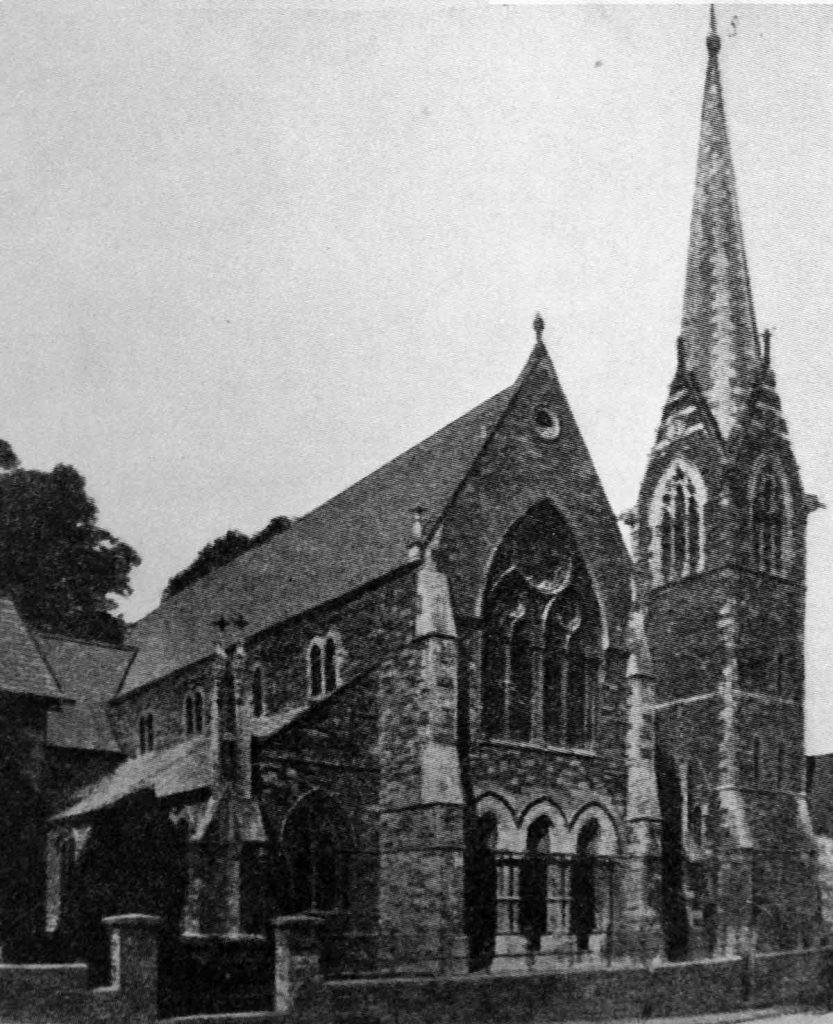

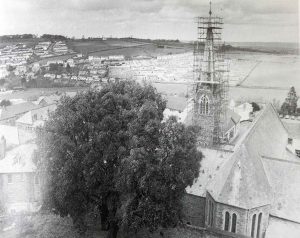

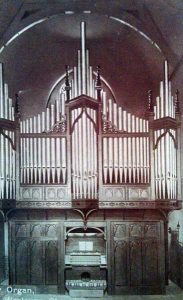

The present Chapel (above) at the top of Castle street is the third to stand there. The second, built in 1862, lasted only eight years; the roof was too heavy for the walls, and these were soon shored up by timber. Then, in 1870, the present building was erected. The site once held a school upon it, kept by Elizabeth Treise, and this leads on to the consideration of the day school in the old Tower street premises kept by William Pulton. This later became the British School for Girls, with the British School for Boys in separate premises at Western road (later the Board School and now the offices of Stags, estate agents). These British Schools were the Methodist equivalents of the National (Church of England) Schools in the days before state education, when – indeed, as in medieval times – the Churches were the mainstays of education.

‘LOST’ FOUNDATION STONE

Through the passage of time, it too provides a mystery: what has happened to its foundation stone? Several people have tried to find it (it was described at the time as “a massive block of granite”) but without avail. It is improbable that the inscription, if there was one, would have worn off, so it may be that it was never inscribed. However, the likely explanation is that it has been buried, especially as the entrance to the Chapel is a few feet higher than the street outside. Underneath that stone was placed in 1869 a bottle containing a list of subscribers, a Circuit plan, etc., a “time capsule”.

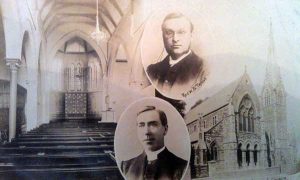

OPENING RAISED £500

The cost of the new chapel was estimated, in 1869, as £3,772, but in fact it worked out at nearly £1,000 more, a very large sum for those days. However, £500 was forthcoming at the opening alone. It was written at the time, “the chapel, schools and classrooms are now not only a most commodious property, but form a group of such rare beauty as to be seldom excelled, if equalled, in the connexion.” The stone was laid on November 17th, 1869.

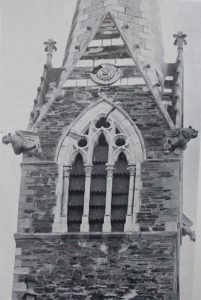

“BIG WESLEY”

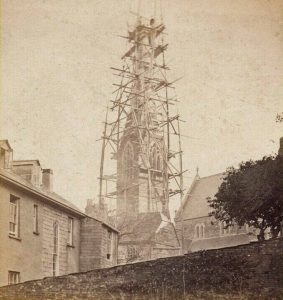

The work on the chapel, school and classrooms were almost complete by the end of October 1870, but the crowning stone on the spire was delayed until the Friday morning on the 4th of November when the opening ceremony took place. Just two months previous on the 5th of September, the trustees bought from the Corporation the ancient ‘town rents’ with which the property was previously charged, thus forever freeing it from the incidence of copyhold tenure. The walls of the structure were built of a mixture of cheaper Bath stone (instead of the more durable Portland stone), Polyphant stone and Cornish granite with the angles of the spire being of wrought limestone. The general contractors were Blatchfords of Tavistock.

Whilst the building work took place the congregation worshipped in the Western Subscription Rooms. It was at this time, headed by John Dingley of Eagle House, a large scheme of chapel building throughout the circuit was undertaken and chapels were opened at South Petherwin, Pipers Pool, Yeolmbridge, Tregada and North Petherwin.

In 1875 an extension was built at the cost of £955. In 1891 in memory of John Dingley, a new building was added to the right of the chapel, now known as ‘the Dingley Hall’ and opened by Thomas Brooks Hender, the sermon being preached by Rev. Mark Guy Pearse. The large room overhead is capable of holding 125 people and has a five-light memorial window to the memory of John Dingley. On the ground floor is a spacious reading room.

The spire soon became known affectionately as ‘Big Wesley’!

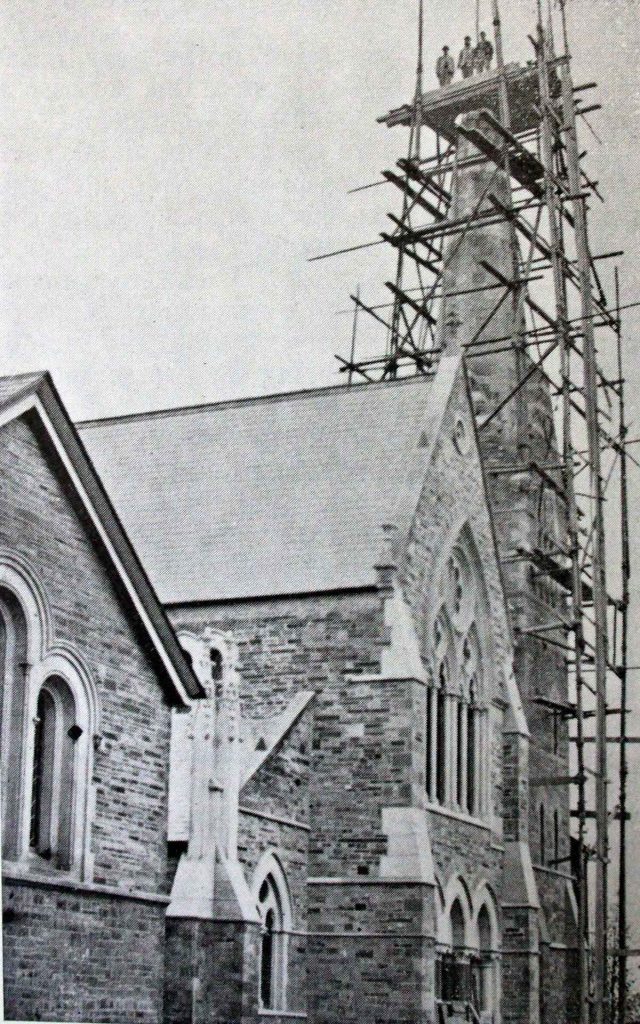

It was the use of the cheaper stone that was to cause concern in the following years with the architect James Hine being asked to make a detailed report on the spires condition just 12 years later. He put together a plan to make good the defects found which was carried out in 1883 by Congdons.

However this only proved to be a small redress as in 1901, James Hine made a further inspection and found that the masonry, especially the freestone, was decayed in many places (below left). The report concluded that through the lofty position of the spire, its exposure to the elements had tested its structure, but he stated that it had not affected the general stability of the structure. A very thorough restoration was needed with the defective Bath stone being taken out and replaced with Portland stone. The report was adopted and the repair work was carried out by Ambrose Andrews of Plymouth at a cost of £306 10s. 0d. In 1912 electric lights were installed with a further renovation being carried out to a total spend of £349 17s. 0d. The very bad weather of January and February 1963 caused further damage to the spire and left it in a very dangerous condition. Work was carried out to make it safe by J. F. Dawson brothers of Bodmin to a cost of £1,049 4s. 0d.

By 1984 though, ‘Big Wesley’ was again in a very dangerous state and with the high costs of repairing it, the decision was made to take it down and with it an iconic symbol of Launceston’s skyline disappeared forever (below right).

One of the most notable Wesleyan figures was William Browning, who died in 1896 at the age of 100. Even when ninety years of age, he would walk from Launceston to Lanhargy or Bowithick or Altarnun or Rilla Mill to preach; his last sermon was delivered at Bowithick when he was 96! A grandson, Alfred Browning Lyne, became chairman of the Cornwall Education Committee and was founder-editor of the Cornish Guardian.

BAS-VOIL BAN

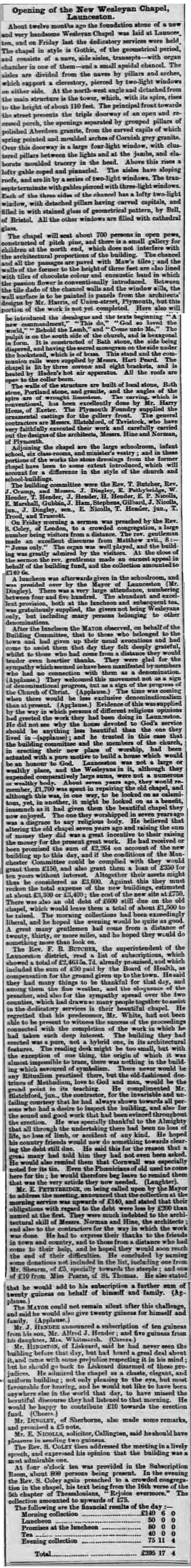

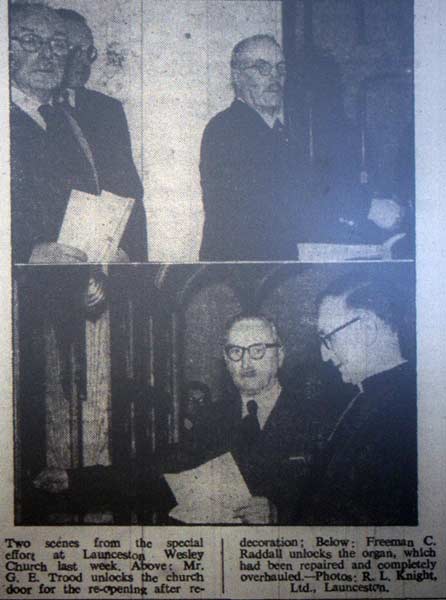

While “Methodism was born in song” and has so continued, orchestral instruments were an early feature of accompaniment. Frowning, the Trustees of 1829 forbade the use of their bass-viol for any other purpose than at chapel, while in 1832 “those singers (probably members of the choir) who had attended the Theatre” were admonished for their action and informed by letter of “the inconsistency of one night taking a part in the theatre and another in the House of God.” Dramatic performances were viewed with horror. When the Rev. Childs Clarke, Headmaster of the Grammar school and Vicar of St. Thomas, introduced them for the boys at his school, prayers were offered in at least one chapel to counteract the supposed evil. A harmonium was introduced in 1861, but there was a strong feeling against it, and it was not until 1870 that an organ made its appearance (with £1 a year for the organ blower!). A remarkable record of service was set up by Mr Stanley Parsonson: he was appointed organist in 1893 and continued for the rest of his life, being succeeded by Mr W. P. Leverton in 1947. In 1909 a grander organ was installed at a cost of £759: its restoration in 1951 entailed a £2,500 appeal.

Visits: 277