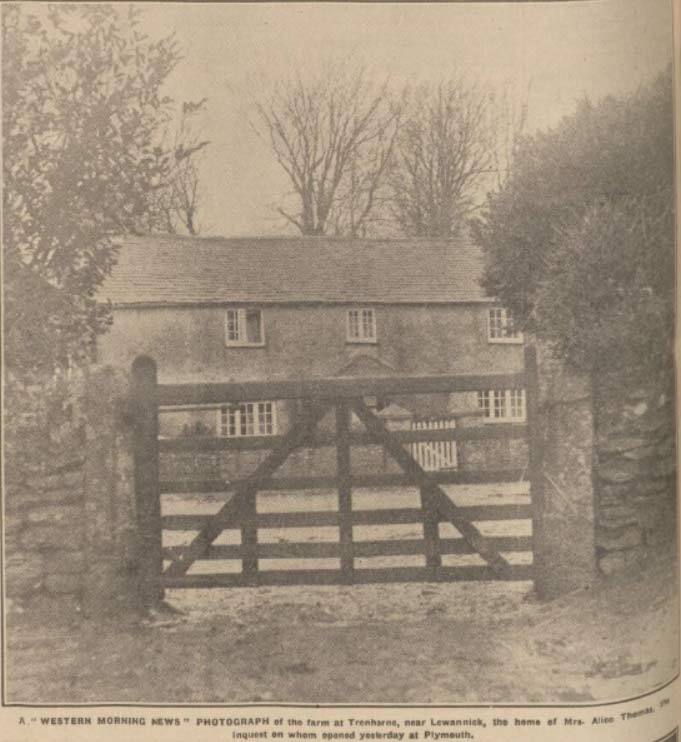

Trenhorne is a small hamlet between Lewannick and Congdons Shop and even today it only has about a dozen houses, so can quite rightly lay claim to being a sleepy hamlet however during the winter months of 1930/1931 the whole world seemed to have its eye upon it, with the national press featuring daily headlines into the circumstances surrounding the death of Alice Thomas wife of William Thomas of Trenhorne Farm and a family friend, Sarah Ann Hearn (Annie) of Trenhorne House. William and Alice had been married for twenty years and had been farming at Trenhorne farm since 1928. Alice was born in 1887 to Samuel and Tryphena Parsons the eldest of six children (four daughters, two sons) at Tremaine, Egloskerry. Her father was a farmer. William was born in 1889 at Catchfrench, St. Germans to William and Elizabeth Thomas. His father was also a farmer.

Annie was born in 1895 at Middle Rasen, Lincolnshire to Robert and Betsy Everard. Her father was a gardener. She was stated to have married a Sheffield doctor, Mr. Hearn, in 1919, but who died just a few days after the wedding and as evidence showed her relatives a photo of him. However, after the ‘Daily Sketch’ published the photograph it soon came to light that she had deceived everybody, as the photo was that of a Territorial Officer who had died of his wounds on March 25th, 1917, two years before the alleged wedding. He was the youngest son of Charles and Florence Vane-Tempest, and the great grandson of the third Marquess of Londonderry. The photo had been taken by a traveling photographer and its seems the he had sold prints to a Sheffield studio, and it is believed that this is where Annie purchased one of the prints. This, coupled with no records of any wedding having taken place, does throw some doubt as to her rational state,(This deception was never challenged in the later trial).

Annie and her sister Lydia ‘Minnie’ Maria Everard, had moved to Weston-Super-Mare from Harrogate in November, 1919, living for a time at Spring-hill, Worle, a village on the outskirts of Weston. The following month they moved into High Street, Weston, renting two two rooms in a boarding-house. Whilst here the two sisters were charged with stealing jewellery. Minnie was discharged, but Annie was committed for trial. However, at the Somerset Quarter Sessions she was also discharged. The two sisters then moved to Devon before finally arriving at Trenhorne, Congdons Shop to live with their invalid Aunt, Mary Ann Everard.

Above Alice Thomas, Lydia Everard and Annie Hearn.

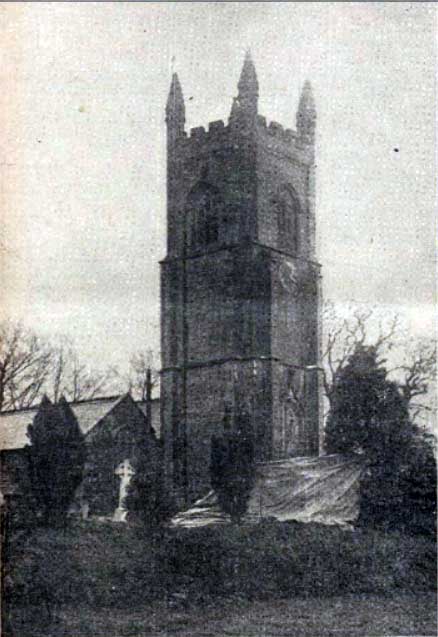

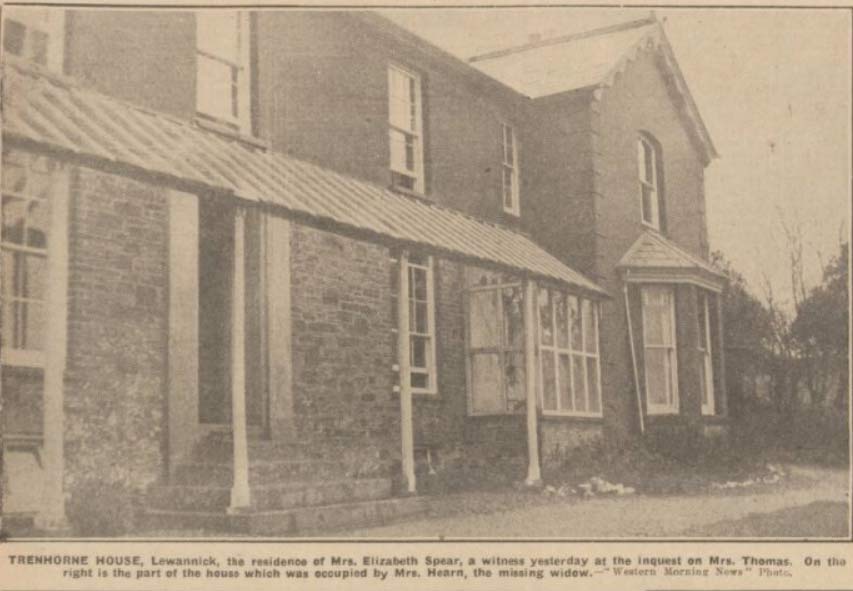

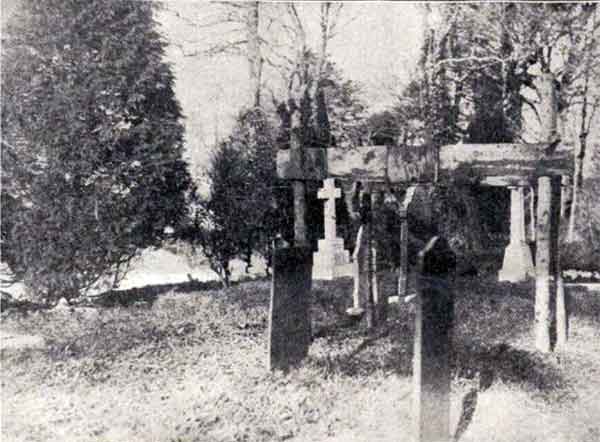

Trenhorne House was split into two, with half rented to Annie Hearn. Annie helped nurse both her Aunt and her sickly sister, but both had died, and were buried in the Lewannick churchyard. Minnie had been suffering from illness for some time particularly of stomach problems

Annie Hearn’s threadbare existence at Trenhorne House meant taking in the occasional lodger and baking little cakes and pastries to sell. In 1928, when she was truly struggling to make ends meet, her neighbour, William Thomas, gave her a loan of £38.

Rumours were rife that Anne often flitted down a secluded track behind Trenhorne House to visit Mr Thomas at Trenhorne Farm, a 17th century farm near Lewannick.

On October the 18th 1930 Annie was invited by William Thomas (seen left) to an outing by the coast with him and his wife Alice. Annie prepared the picnic of tinned salmon sandwiches, dressed with her own recipe salad cream. When tea and cakes were ordered at Littlejohns cafe at Bude, Anne produced the sandwiches, and Alice eat one or two with William and Annie having one apiece. Later Alice told William that she had a “sweetly taste” in her mouth, and after they had started for home she began to be sick. On arriving back at Trenhorne Anne was asked to stay and look after Alice and from that time to October the 29th all of the food was cooked by Annie. The doctor was told that Alice had eaten fish sandwiches and it occurred to him that she was suffering from some form of food poisoning. He prescribed kaolin and told Alice to live on whitebait and water. Alice was nursed according to the doctors instructions by William and Anne. However, on the 3rd of November, the doctor, Dr. Saunders, realised that the case was not one of simple food poisoning, and called in Dr. Lister, of Plymouth, who found Alice was suffering from peripheral neuritis, a form of arsenical poisoning. Alice was immediately admitted to hospital at Plymouth but her condition was so serious that she passed away the following morning, aged only 43. The analyst found in the organs .85 of a grain of white arsenic, a form obtained from weed killer.

On October the 18th 1930 Annie was invited by William Thomas (seen left) to an outing by the coast with him and his wife Alice. Annie prepared the picnic of tinned salmon sandwiches, dressed with her own recipe salad cream. When tea and cakes were ordered at Littlejohns cafe at Bude, Anne produced the sandwiches, and Alice eat one or two with William and Annie having one apiece. Later Alice told William that she had a “sweetly taste” in her mouth, and after they had started for home she began to be sick. On arriving back at Trenhorne Anne was asked to stay and look after Alice and from that time to October the 29th all of the food was cooked by Annie. The doctor was told that Alice had eaten fish sandwiches and it occurred to him that she was suffering from some form of food poisoning. He prescribed kaolin and told Alice to live on whitebait and water. Alice was nursed according to the doctors instructions by William and Anne. However, on the 3rd of November, the doctor, Dr. Saunders, realised that the case was not one of simple food poisoning, and called in Dr. Lister, of Plymouth, who found Alice was suffering from peripheral neuritis, a form of arsenical poisoning. Alice was immediately admitted to hospital at Plymouth but her condition was so serious that she passed away the following morning, aged only 43. The analyst found in the organs .85 of a grain of white arsenic, a form obtained from weed killer.

The local newspaper reported that it cast “quite a gloom over the parish”. Neighbourhood gossips were less discreet. When a post-mortem examination found that Mrs Thomas’s body was riddled with arsenic, suspicion was soon cast towards Annie Hearn.

On the night before Alice Thomas died, Annie went next door to ask Elizabeth Spear for some hot washing-up water. She had helped nurse Alice Thomas in her last agonies at Trenhorne Farm, but she had had to leave. “I can’t stay down there any longer,” Annie told Mrs Spear. “They seem to think I poisoned Mrs Thomas with the sandwiches. Down there,” she added, nodding towards the farm, “they think all tinned food is poisoned.”

At Alice Thomas’s wake, her brother Percy Parsons (pictured left) cornered Annie Hearn. “I’ve heard about you,” he stated, “and them tinned sandwiches you was responsible for. What d’you put in them? That’s what I’d like to know.”

At Alice Thomas’s wake, her brother Percy Parsons (pictured left) cornered Annie Hearn. “I’ve heard about you,” he stated, “and them tinned sandwiches you was responsible for. What d’you put in them? That’s what I’d like to know.”

William though, invited Anne to stay at the farm. But being distraught at the accusations she returned to her home. Two days later, William received a letter from her.

“Dear Mr Thomas,” it began. “Goodbye. I am going out if I can. I am innocent, innocent. But she is dead and it was my lunch she ate. I cannot stay. When I am dead they will be sure I am guilty, and you at least will be clear. Tell them not to worry about me.”

William fetched a police officer, and together they broke into Trenhorne House. But Anne Hearn had vanished.

At the inquest into Alice Thomas’s death, a local chemist (Shuker and Reed) said he had supplied weed-killer for Anne Hearn’s overgrown garden four years earlier, a powder that was practically “all arsenic”. Although this was a commonplace remedy for weeds, the inquest verdict was one of “murder by arsenical poisoning by person or persons unknown”.

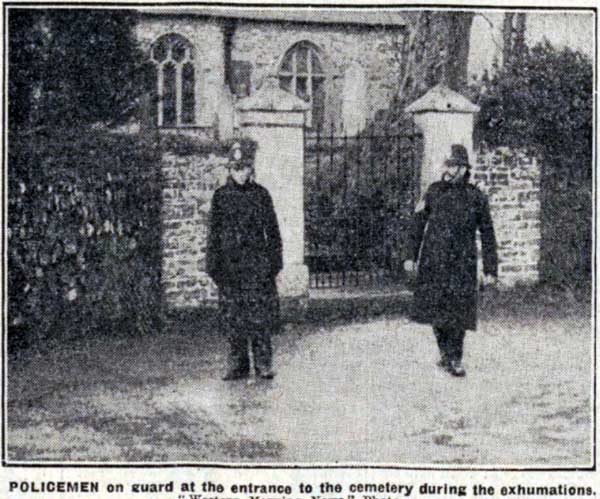

While the hunt for Annie Hearn continued, police investigated the deaths of her aunt and sister, exhuming both bodies because their fatal symptoms were consistent with arsenical poisoning. The Home Office analyst duly reported finding “distinct quantities of arsenic” in both. The question that was now raised had Annie Hearn murdered a further two woman?

This then became major news especially the manhunt with the national newspapers showing a keen interest. The ‘Daily Mail’ went as far as offering a £500 reward for her arrest.

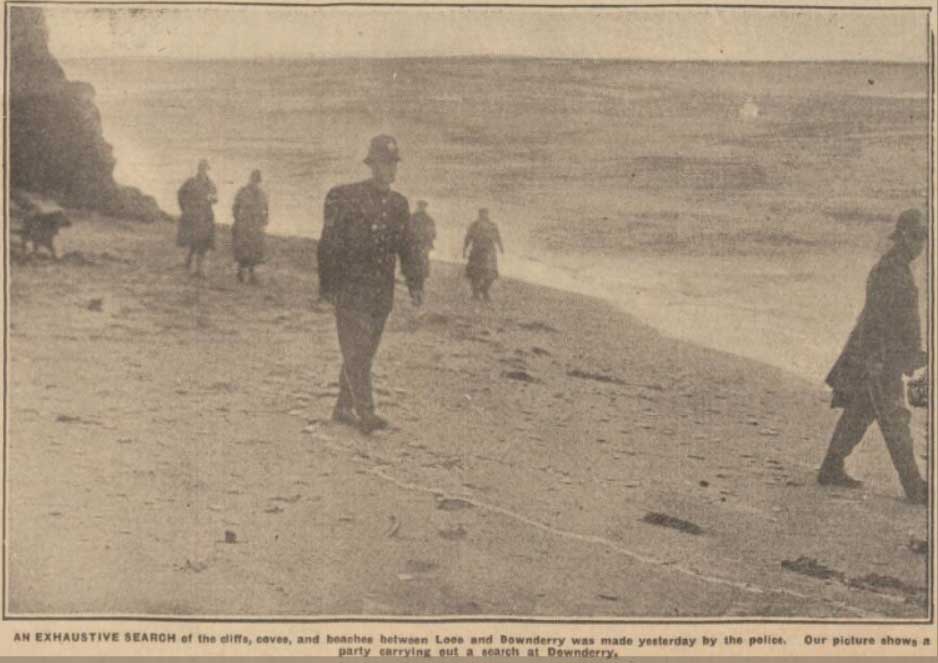

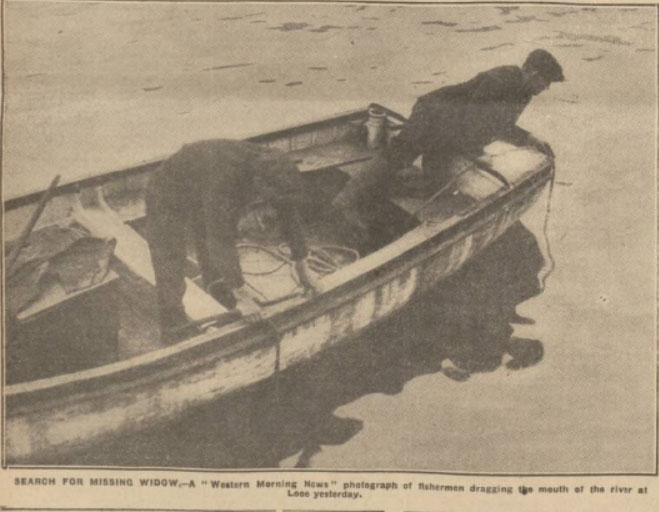

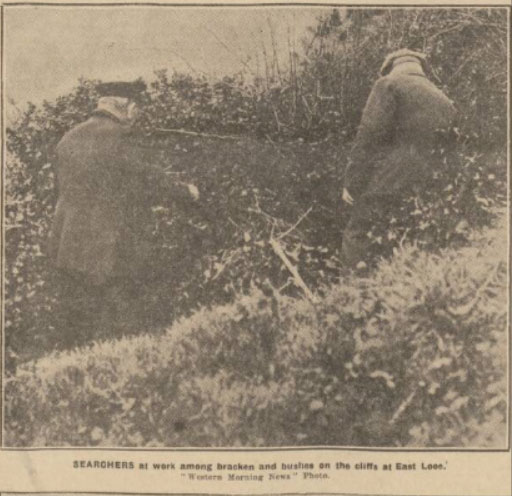

Annie’s checked coat was found on a clifftop at Looe which called into question the possibility of suicide, but after an extensive search there was no sign of a body. There were even suggestions in the press that she could be lying at the bottom of a well or mine shaft in the Lewannick area and asking questions as to why the police had not searched those areas. A tramp witnessed seeing a woman wandering around the roads of Lanhydrock near Bodmin so a wide search of that area was completed with no success.

Above and below the search for Annie Hearn takes place around Looe in 1930.

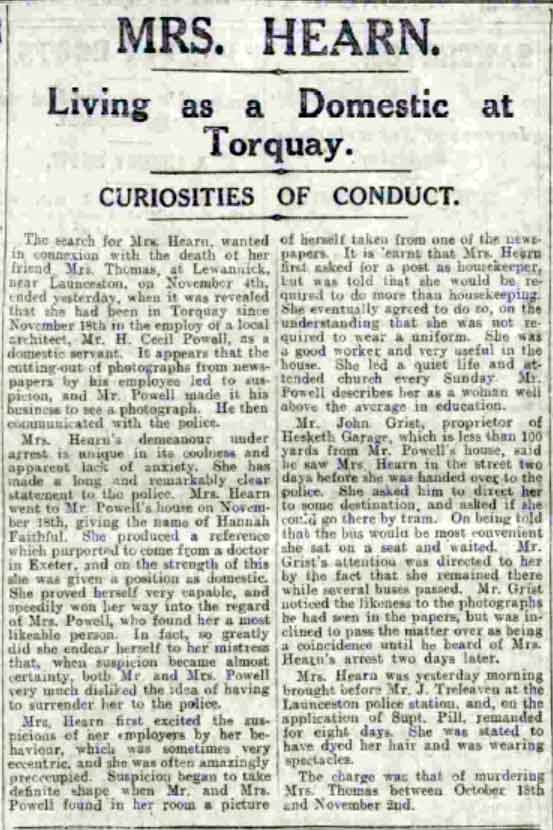

She was eventually traced to Torquay where, under the alias of Mrs. Faithful, she had taken a post as housekeeper to architect Cecil Powell of Brooksby House(below right). Although she performed her duties with the utmost professionalism he grew suspicious of some of her actions and although she had dyed her hair and wore glasses he recognised that she resembled the picture of the

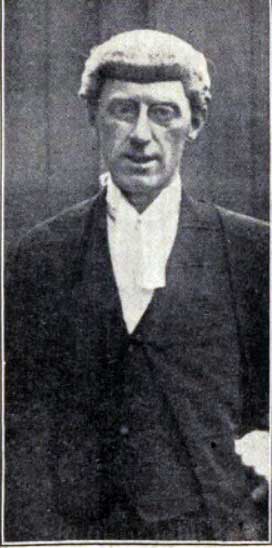

Cecil Powell, feeling sorry for Annie, donated his £500 reward for finding the fugitive towards her defence. This meant that she could afford one of Britain’s best barristers, Norman Birkett K.C..

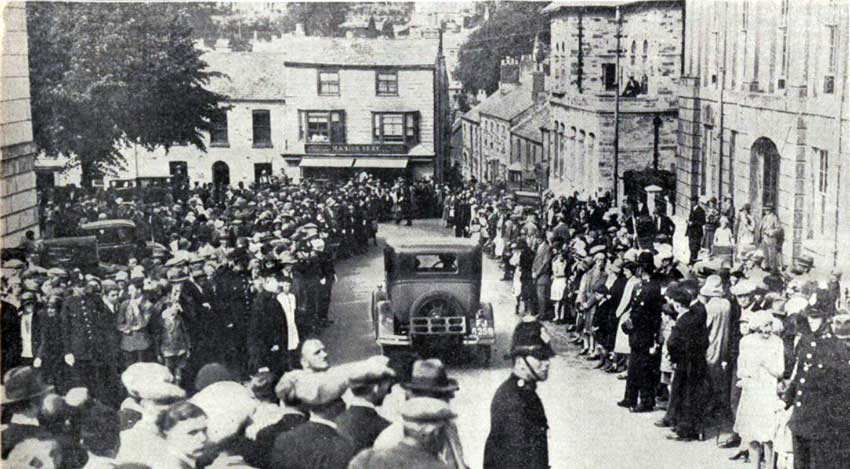

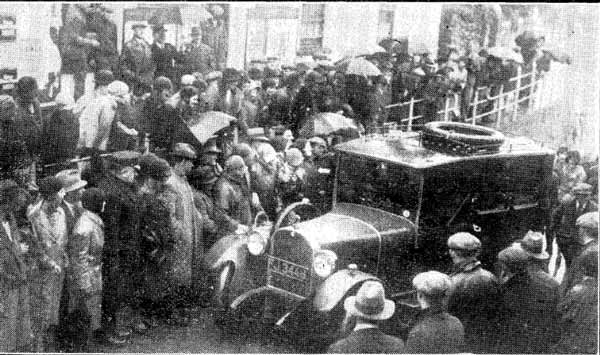

Above Annie Hearn is brought and taken away from Launceston Police Station.

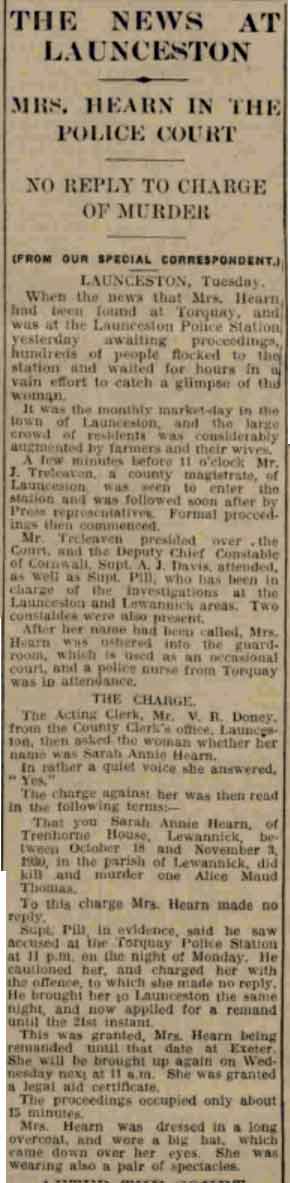

After numerous initial police court hearings, Anne was remanded in custody to appear at Launceston magistrates court on March the 10th On the charges that she murdered her sister Lydia Maria Everard, on the 21st of July 1930, and Mrs. Alice Maud Thomas on the 4th of November 1930. The public interest was immense with queues forming outside Launceston

That, he declared, was not enough and for nearly three quarters of an hour examined the evidence in an endeavour to prove the strength of his point. During the whole hearing Anne was heard to utter only these six words “Only that I am not guilty”

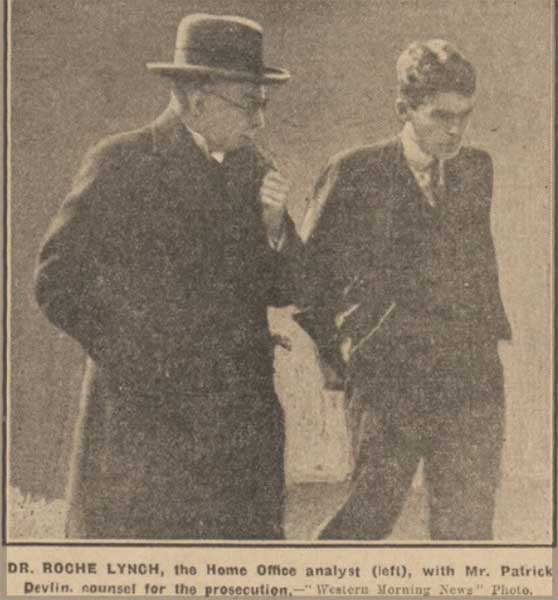

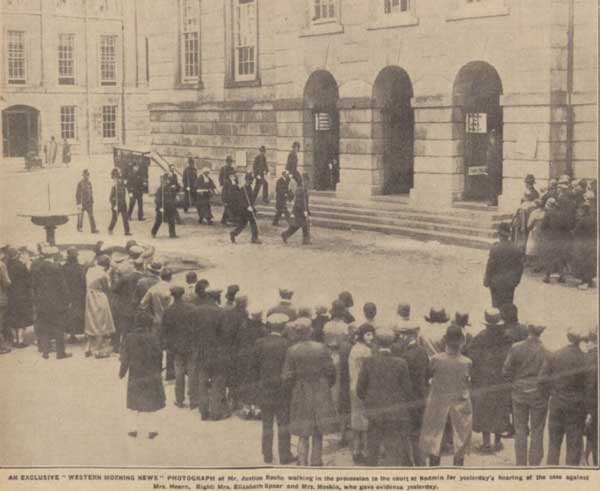

Above left Elizabeth Spear and Mrs. Hoskin who gave evidence in the Annie Hearn trial. Above right Norman Birkett and Prof. Smith and Dr. Roche Lynch.

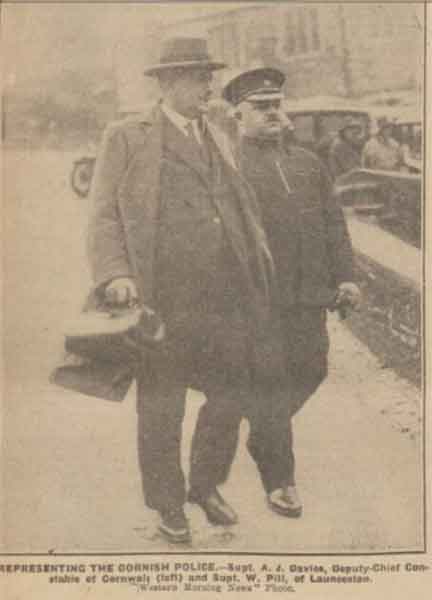

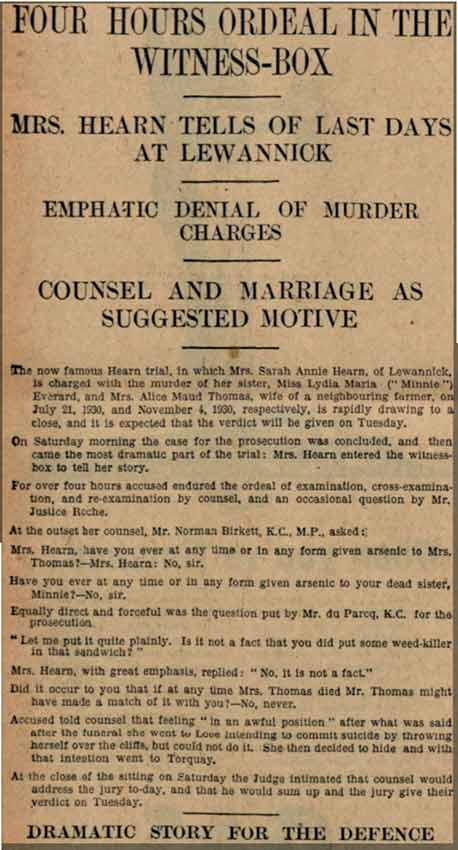

The trial took place in June 1931 at the Bodmin Assizes under a blaze of local and national interest with queues of people

outside waiting to gain access to the limited room available in the public gallery. Nearly every newspaper in the country was represented with the smallest amount of detail being published. A ten man and two woman jury were empanelled for the trial.

On the opening day counsel debated for two hours, two points in the evidence which had been tendered by the Crown against the accused. Dr. H Du Parcq., K. C., leading for the Crown, submitted that after he had opened the indictment charging Annie Hearn with the murder of Mrs. Thomas he should be allowed to introduce a diary alleged to have been left by Lydia Everard. He also submitted he should be allowed to tender evidence that Miss Everard died of arsenical poisoning, so as to show that the likelihood of Mrs. Thomas having been poisoned accidentally was more remote than if there were no other history of arsenical poisoning in this case. Mr. Justice Roche ruled that the diary was not admissible, but that evidence concerning Miss Everard’s death was relevant.

Much of the early part of the trial was taken up with medical and forensic details with evidence from the respective Doctors that had treated Lydia Everard and Alice Thomas including the Launceston Doctors Gibson and Galbraith. The prosecution finished their case for conviction on the 19th of June, with Mr. Norman Birkett K. C. opening the case for the defence the following day. Annie Hearn was the first called to give evidence in her defence and endured four hours of examination, cross- examination, and re-examination by counsel.

Birkett then tore into the crown case by discrediting the forensic evidence, showing that the presence of arsenic in the exhumed body of Mrs Hearn’s sister, Lydia, could be blamed on high levels of naturally occurring arsenic in the ground of Lewannick churchyard.

“Am I right in saying that a piece of soil so small that you could hold it between your fingers dropped on to this body would make every calculation wrong?” Birkett asked one of the prosecution experts.

“Yes,” the analyst replied.

More drama occurred in the summing up when Dr. H Du Parcq collapsed into the arms of his clerk when 27 minutes into his speech. The Judge adjourned for half an hour so that Dr. Du Parcq could recuperate and on his return was allowed to remain seated for the remainder of his speech which was one hour fifty minutes long, whilst Mr. Birkett’s lasted for 3 hours 55 minutes.

On the 23rd of June Mr. Justice Roche took four hours to sum up the evidence, where necessary advising the jury on points of law, and then at 3:12 pm the jury retired to decide Anne Hearn’s fate, who for the first time during the hearing, broke down and cried, and had to be helped from the dock. The jury returned after an hour to what was described as an atmosphere that seemed oppressive. The clerk to the assize asked the foreman of the jury if they were agreed upon their verdict. Annie Hearn stood deathly pale as the foreman pronounced ‘Not Guilty’ and many women in court, including Anne’s nurse, sobbed.

After an eight-day trial, the jury, had been persuaded by the defence that Alice Thomas had died of food poisoning. Yet the case for murder remained compelling. “It is no use beating about the bush,” Mr Justice Roche said in his summing-up. “The issue is down to two people – Mrs Hearn and Mr Thomas.”

So if Annie Hearn was innocent, was William Thomas guilty? The judge wondered if, Annie Hearn aside, there “may have been some other women who moved him to passion”, and there were various post-trial rumour’s doing the rounds in and around Lewannick about just such a woman. William Thomas left Trenhorne and the area, living the rest of his life on a remote farm near his birthplace of St. Germans as a recluse until his death on the 14th of December 1949.

Above Annie Hearn is led from the court room and driven away after being found not guilty.

Annie Hearn never went back to Trenhorne House. The contents, including a piano and violin, were auctioned off during her trial (below), to a crowd who packed every room for the viewing. Her fate remains as much a mystery as the case itself. After the trial she traveled up to Yorkshire where she stayed with another sister, and it is assumed continued to live in the North possibly changing her name again, but nothing was heard of her after her trial.

“Thank God, it is all over,” she confided after her trial. “One thing is certain – when I have cleared up my business in Cornwall, I shall never return here again.” And she never did. As for the relatives of Alice Thomas, they were never convinced of Annie Hearn’s innocence with the trial putting a tremendous strain on the family.

Above left Annie Hearn. Above right Lydia and Annie.

Visits: 275