.

With thanks to the Nicolls family.

Marian was born in 1876 to Edward and Ellen Nicolls at Holloway, Middlesex. Her father was a House furniture and blind maker. Originally from Launceston Edward moved around the country with his family before settling back in his home town in about 1888, setting up home in Broad street. On leaving school Marion or May as she was known to her family, trained as a chemist. In 1911 she was living at Shaftesbury House, Orchard Street, Burton on Trent and was working as a Doctors Dispenser. She became a strong believer in Women’s suffrage and was a member of the Launceston Society for Women’s Suffrage taking on the role of assistant secretary.

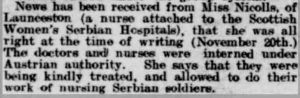

She joined the Scottish Women’s Hospitals working in the Serbian unit (NICOLLS Miss Marian, Clerk Valjevo 1-Apr-15 12-Feb-16). She was taken prisoner by the Austrian’s in 1915 and released in January 1916. She then joined the French Red Cross serving in various hospitals in France during the balance of the war. She was awarded Women’s Services and, Distinguished Conduct Medals.

A Scottish Women’s Hospital led by Dr Eleanor Soltau was dispatched to Serbia. Other units quickly followed and Serbia soon had four primary hospitals working night and day. The conditions in Serbia were dire. The Serbian army had a mere 300 doctors to serve more than half a million men and as well as battle casualties the hospital had to deal with a typhus epidemic which ravaged the military and civilian populations. Serbia had fought a surprisingly successful military campaign against the invading Austrians but the fight had exhausted the nation. Both soldiers and civilians were half starved and worn out and in those conditions diseases thrived and hundreds of thousands perished. Four SWH staff, Louisa Jordan, Madge Fraser, Augusta Minshull and Bessie Sutherland died during the epidemic. By the winter of 1915 Serbia could hold out no more. The Austrians had been joined by German and Bulgarian forces and again invaded and the Serbs were forced to retreat into Albania. The SWH staff had a terrible choice to make, stay and go into captivity (or worse) or go with the retreating army into Albania. In the end some stayed and some went. Elsie Inglis, Evelina Haverfield and others were taken prisoner and were eventually repatriated to Britain. The others joined the Serbian army and government in its retreat and suffered the indescribable horrors of that retreat and shared the hardships endured by the Serbian army.

A Scottish Women’s Hospital led by Dr Eleanor Soltau was dispatched to Serbia. Other units quickly followed and Serbia soon had four primary hospitals working night and day. The conditions in Serbia were dire. The Serbian army had a mere 300 doctors to serve more than half a million men and as well as battle casualties the hospital had to deal with a typhus epidemic which ravaged the military and civilian populations. Serbia had fought a surprisingly successful military campaign against the invading Austrians but the fight had exhausted the nation. Both soldiers and civilians were half starved and worn out and in those conditions diseases thrived and hundreds of thousands perished. Four SWH staff, Louisa Jordan, Madge Fraser, Augusta Minshull and Bessie Sutherland died during the epidemic. By the winter of 1915 Serbia could hold out no more. The Austrians had been joined by German and Bulgarian forces and again invaded and the Serbs were forced to retreat into Albania. The SWH staff had a terrible choice to make, stay and go into captivity (or worse) or go with the retreating army into Albania. In the end some stayed and some went. Elsie Inglis, Evelina Haverfield and others were taken prisoner and were eventually repatriated to Britain. The others joined the Serbian army and government in its retreat and suffered the indescribable horrors of that retreat and shared the hardships endured by the Serbian army.

A Returned Prisoner of War (Cornish and Devon Post report Saturday February 19th 1916 transcribed by Roger Pyke)

Miss Nicolls Home-coming.

After being a prisoner of war in Austria for two months, Miss Marion Nicolls is home again with her people in Launceston. She arrived by the last train from London on Monday evening (14th of February), and had a warm welcome from a party of relatives and friends who had been waiting more than an hour for the overdue train. Her father and sister had brought with them a dapper little terrier called ‘Chum’ the personal property of Miss Nicolls and although Chum had not seen his mistress for twelve months, he knew her so soon as she alighted from the train, and was evidently very delighted.

Miss Nicolls has been through some exciting times in the theatre of war where the latest sensational developments have taken place. A conversation at the tea table enables us to give our readers the interesting story of the work of the Scottish Women’s Hospital Serbian Unit, to which Miss Nicolls was attached in the capacity of secretary, and to which for some time she acted in her professional capacity as pharmaceutical dispenser. In reply to congratulations on her return home safe and sound, Miss Nicolls said she felt wonderfully well. She did not know exactly what was her position as a returned prisoner of war, and how far it affected her contract with the Scottish Women’s Hospital undertaking, but she was ready, after a short rest, for any call of patriotism that might come to her.

The account that Miss Nicolls gave of her journey home through troubled Europe was extremely interesting. The members of the Scottish Hospital Expedition, over thirty in number, all of them women, including the doctors, were prisoners under Austrian rule at a place called Kecskemet, in Hungary. On February 2nd Miss Nicolls dispatched to her father and mother in Launceston a telegram containing three words, which she had to put in German, ‘Interned, well, love,’ what happened to this telegram no one knows, but it arrived here two days after in a form that very much puzzled the parents. This is how it read:

‘Prisonniere Guerre Interne Bien Chere May Croix rouge hongroise Fargo Bela Vermatten Krosremet’.

Happily there were not many days to wait for the best possible explanation of the puzzle. At the time this telegram was sent off, one of the lady doctors with the unit was handing in a telegram and there was some conversation about the need of money for the prisoners. ‘You will need no money,’ said the telegram clerk, ‘for you will be leaving tomorrow for your own country’. That was the first intimation Miss Nicolls and her friends had of their approaching release. They understand they are in the position of exchanged prisoners and at first thought that they were set against the Consuls who had been taken prisoners at Salonika. This, however, is a matter of conjecture.

Which way did we come home? Well, said Miss Nicolls, the day after the telegram we left Kecskemet – the name is not so difficult to pronounce when it is remembered that ‘os’ in Hungarian has the value of ‘oh’ in English – we were sent across the Danube to Budapest, thence to Vienna, and afterwards by way of Brouck we passed from Austria to Swiss territory at Feldkirch. Here our luggage and effects were minutely overhauled by the Austrian authorities. They took from me my diary, several maps, postcards I had received, and even a paper patter of a skirt band. Yes, they took my address with a view to returning these things after the war. We came through France and returned to England by the Dieppe and Folkestone route. At Folkestone I left my party and spent a little time with my two brothers who are in the army. I then proceeded to London and saw another brother who has been attested but for the time is pursuing his occupation on the staff of the Regent Street Polytechnic.

A Correction

On being asked to tell the story of the expedition, Miss Nicolls said she had seen accounts of it in various newspapers but there was one error which she should like to correct. It had been said that the Unit had refused to nurse cholera patients. This was not true. They had only once been asked to do this and they agreed to do it. All arrangements were made; they were inoculated against cholera and purchased rubber gloves, but at the last moment the authorities changed their minds and they had not this work to do.

The Expedition

When did our expedition set out? The Scottish Women’s Hospital Serbian Unit, made under Dr. Alice Hutchison, M.D., and numbering about fifty women – doctors, nurses, sanitary inspectors, etc.- left England for Serbia on April 20th, last year. No, I was not one of the nurses; I was secretary. Afterwards I took on the work of dispenser temporarily owing to the non-arrival of the dispenser who had been sent out. The expedition was held up at Malta for a month by Lord Methuen, the governor, who requisitioned our services for the first wounded that, came from the Dardanelles.

Reaching Serbia through Salonika we opened our hospital with 200 beds in June at Valjevo, in Serbia. By that time the war was in progress. The Bulgarians and the Serbs were at close grips. At that time we were about 70 miles from the scene of the fighting. Our hospital primarily was for the treatment of fever, especially enteric fever. The Serbians had plenty of hospitals for the wounded. Our hospital, however, was not filled with fever cases and having the room some of the wards were used for other cases. Some wounded from the field were sent to us. One ward was wholly occupied with scurvy patients.

Capture of the Hospital

After a time we were forced to retire further back down the line. After staying at Pojega we retired still further under pressure of the Austro-German forces. Finally we came to Vrynjachksbanga, where the working of our hospital was taken over by the military. The war had been getting nearer and nearer to us and we could hear the sound of the guns. We were taken prisoners.

Austrian Treatment Not Unkind.

Did that make much difference? No, we went on with our hospital work. The chief difference was that a man with a fixed bayonet was placed in front of the hospital on sentry duty. Our captors forbade any of the staff to leave the hospital and safeguarded the front, but strange to say that we were treated very nicely by the military authorities. The Austrian commandant, Prince Lobkovita, was very courteous and even jovial towards us. We were there only about a fortnight as the Austrians wanted us to undertake a hospital at Krushetavn. We packed up everything and took our equipment to the hospital there. The people were very sorry to see us go. We were there, however, only five days, being accommodated in a hotel and soon we were to realize that we were prisoners. We were taken to Ctalach and shut up in two railway horse wagons, guarded by soldiers. Our party had been reduced to thirty-four in number.

German Soldier’s Curiosity

How many were there of us? Let me see thirty-four. Before we were taken prisoners, some had trekked back to England through Montenegro, having the right to leave after concluding a term of six months service. For many people that is quite long enough a strain under such circumstances. Liberated from the horse wagons our party reached Semindria, on the River Danube. While we were waiting for three hours on the quay German soldiers walked round looking at us and making curious if not insulting remarks. We went over by the last boat. It was then fairly late at night. We were accommodated in a military hut. Our German guard was a quiet and nice boy who shared his loaf with some of us who had had nothing to eat for twenty-four hours. Dr. Alice Hutchison carried out her duties as head of party with very great efficiency. She frequently interviewed the officials, pointing out to them that they were not regarding the Geneva Convention of which we found to our astonishment that some of the officers had never heard. Our next stage was Kevevara where we were put in a refugee’s night shelter for some time and then transferred to a police station, where we were three weeks.

Fatiguing The Guard

Here we find that our pedestrian activity caused some trouble. Our military escorts complained of being tired out by our rapid walking and the long distances we went. They complained to their officers that we took them too far and walked too fast, or as one put it ‘they fly through the mud like geese’. One captain, explaining the difficulty to us, said ‘these men are not used to walking like you are’. It was pointed out to him that exercise was necessary to health, and so when he knew that we wanted to go for a walk he arranged to send the strongest man he could find off duty to rest awhile so that he might be fit to take charge of us in our walk. Soon after we were removed to Kecskemet. We started thence to England last Saturday week – thirty-four of us and others who had been rounded up with us.

Without News

Had we been without news all the time? Yes, I had not heard from home since the beginning of October; previously I had heard regularly. During the whole of that time we had to depend for our news upon a German newspaper, ‘The Paster Lloyd’ in which, of course, we could not put much faith.

Hospital Equipment Seized

Was I bound to remain with the party? No, some of our members left for Montenegro at the beginning of November when it was known that it was inevitable that the Austrians would take us prisoners. Yes, I had the choice of trekking through Montenegro or of remaining and taking my chance. The decision to remain was dictated by the desire to save our hospital equipment, worth between three and four thousand pounds. We were in hopes that out Allies would come up to our relief, but that was not to be. Our equipment fell into the hands of the Austrians, but our C.M.O. Dr. Hutchinson, insisted on their giving her a receipt for it a document which I presume will have some value at the end of the war.

At the conclusion of this interesting interview the hope was expressed that the period of rest, which Miss Nicolls so fully deserves, would be pleasant and beneficial. Miss Nicolls said she quite appreciated it and it would doubtless do her much good, but she was ready to go forth again if she could be of any service.

_________________________________________________________

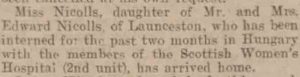

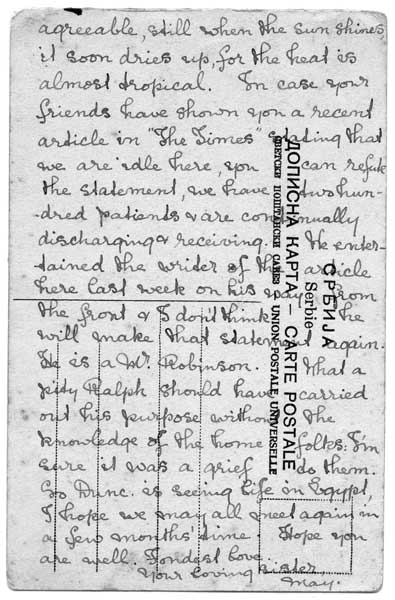

Above Marion Nicolls letter from Valjevo.

After a short rest at home, Marian enlisted with the French Red Cross in France, serving there until May 1917 when she took up a dispensary role at the Royal Victoria Auxiliary Hospital, Netley, Hants. She received ‘The Cross of Honour’ in recognition of her services.

Above left Marion at work. Above right a family group at Cyprus Well, with Marion on the right, her mother in the middle, sister Nance and two aunties from Fowey

After the war, she worked as a dispenser at the Royal Victoria Hospital at Netley, Southampton. In 1920 she returned to Launceston where she took up residence at Cypress Well in Ridgegrove Hill (later the residence of Launceston poet, Charles Causley). She then took up employment with Ambrosia at Lifton as a chemist and its is here that she spent the rest of her working career, finally retiring in 1940. Marion was a strong Liberal and was heavily involved in the parties activities and at one time was the president of the Launceston Women’s Liberal Association. She was also a founder member of Launceston WI and a member of the woman’s section of the British Legion. She also held close ties with the Red Cross and was a deacon of the Congregational Church. Marian was also an ardent member of the Old Cornwall Society. She never married and lived the rest of her life at Cypress Well. It was on Sunday December 28th 1952 that her neighbours noticed that the milk bottles had not been taken in, so the police were called. They made entry and discovered Marian had passed away, having slumped in her bedroom. She was 77 years of age.

Visits: 97