.

Unfinished business.

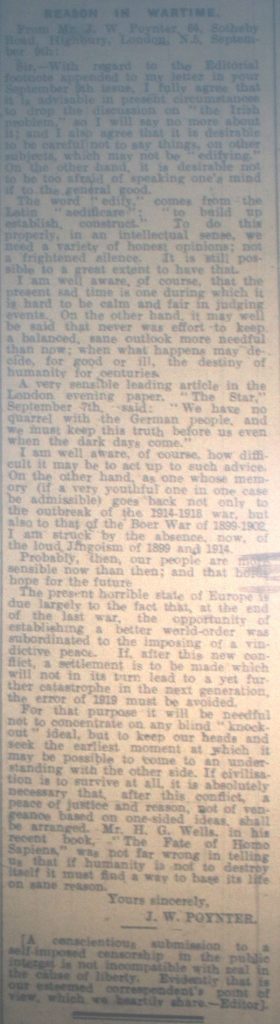

With just a little over twenty years passing, the country was once again at war with Germany which must have been a difficult situation for many to deal with considering the carnage and sacrifices made in the previous war. Well over 200 men from Launceston district gave their lives in what was supposed to be the war that ended all wars. However, the seeds for the second world war were already being in 1918, and not just in the flawed Treaty of Versailles which many on both sides felt inadequate. The French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, who felt the restrictions on Germany were too lenient fortuitously predicted that “this (treaty) is not peace. It is an Armistice for twenty years.” The treaty certainly did nothing to conciliate with Germany and in later years many felt the Germans to be within their own right to ignore the treaty. Ramsay MacDonald, for instance, commented after Hitler’s re-militarisation of the Rhineland in 1936, that he was “pleased” that the Treaty was “vanishing.” This ‘guilt’ was played very well by Hitler with the result that Germany was soon a strong military force.

The Treaty of Versailles a failure as it was, on its own didn’t contribute to the 2nd World War for we also have to look back at the general feeling of many Germans in 1918, particularly the returning soldiers. The surrender had taken place with the bulk of the German army still on French and Belgium soil and for many, they felt undefeated. There was a perception for many that the country had been stabbed in the back, that it was the home front that had lost the war. General Eric Ludendorff was a strong proponent of the ‘stab in the back’ theory, citing that Social Democrats and leftists were to blame for Germany’s humiliation. He also blamed the business element (especially the Jews), as he saw them turn their backs on the war effort by letting profit, rather than patriotism, dictate production and financing. This sense of injustice was nutriment that fed the Nazi’s rise. This is a rather simplistic explanation to the cause of the war, but once you put the depression of the early 1930s into the mix there is little doubt how strong an attribute this all played in the lead up to 1939.

Whatever the individual views on the causes of the war, for the country and more importantly for Launceston and its district the whole way of life were about to change. In World War Two Launceston became a large military centre, with Army units stationed throughout the district; two camps were set up in the town, one at Scarne and the other at Pennygillam. Hotels and houses were commandeered to house secret units, in Dunheved Road were the headquarters of the Royal Navy, Army intelligence, Royal Air Force and planning units, all making plans, firstly, for the defence against German forces invading the coast, then for the coming D-Day invasion of Europe by British and Allied forces when the Americans arrived in the area.

For this invasion, thousands of tons of ammunition, food, clothing, fuel, tanks and means of transport were brought into the area, dumps being set up in fields and woods, etc, all around the area and near the railways. Many of these dumps in sheds, or disguised as haystacks, barns or rises in the land. With this preparation, the many Americans arrived to enhance the planning operations, and to provide the necessary manpower for the handling of the stores, both in the storing and the maintenance and for the swift loading for onward movement to the many ports on the peninsula.

As in WWI, when many horses, complete with harness in many cases, were conscripted for service, guard dogs, active mousing cats, homing pigeons and the likes were put into factories and food dumps, etc., to keep down losses by theft, contamination, and the Western weather.

Go to years 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 World War Two Timeline for the Fallen of Launceston District

1939, the planning for war.

(Much of the following has been gleaned from the various newspaper reporting of the day. The reports became more sporadic in their detail as the war progressed mainly due to censorship but also due to the reduction in the size of the respective papers as a result of the paper shortage. Therefore as the war progressed, there was less being reported particularly once Launceston became a hub used before the D-Day landings, making it difficult to research the military aspect of the town’s role during the war. Wikipedia has also been used to confirm timelines of the war.)

The start of the year saw the area suffering from a large outbreak of a mild form of influenza although some sufferers showed pneumonic symptoms. It was also in January that plans were already being made for the evacuation of children and their teachers by the Ministry of Health on January 10th. The whole of Cornwall bar the Saltash and Torpoint area was highlighted to the reception area for the purpose. It was agreed that all Local Authorities would conduct house to house surveys to ascertain: 1, the amount of surplus accommodation on a standard of one person per habitable room. 2, the amount of this surplus to be found in houses which are suitable for reception of persons removed from other areas and particularly of children; and 3, the amount to be found in houses where the householder is willing to receive either children unaccompanied by their parents or teachers. It was agreed at this meeting that where the householder was unwilling, or willing to only take fewer children, the fact and the reason given were to be noted. Attention was to be drawn to the fact that persons would be found who, though not unwilling to play their part, and not capable of undertaking the care of children – aged and infirm persons living alone, houses where there is a confirmed invalid, and persons living alone whose employment requires them to be absent all day, but who might be willing to take in children on the understanding that a teacher or other helper would be accommodated with them. The proposal was to move children of school age, school by school, in company with their teachers and other helpers. Further, it was intended that the education of the children would continue in the reception areas. Payment to householders providing homes to such children would be paid by the Government at the rate of 10s. 6d. per week where one child is taken, and 8s. 6d. where more that one child is taken. The plan further laid out that children under school age would be accompanied by their mothers or other responsible persons, and in these cases, the householder would be asked to provide lodging only for a payment of 5s. per week for each adult and 3s. per week for each child.

During the first Town Council meeting of the year, held on January 16th, Councillor Sydney J. Fitze (above left) suggested an ambitious plan (and with some irony for the future) to erect a double-decker car park embodying an air-raid shelter for the centre of the town with accommodation for 200 women and children on the old Sheep Market Car Park. He said, “that such a scheme would relieve the present parking congestion in the town, incorporate a bus station – a service which the Council ‘must face up to in the near future’ – and at the same time find work for the unemployed in the town, which was said to be greater than ever before.” In reply, another member, Councillor Pearce, considered the cost of making such a shelter bomb-proof would be excessive, and an alternative suggestion, was that subject to the Duchy’s permission, tunnels be dug underneath the Castle Grounds. Here he thought was an ideal spot, because there were so many parts of the town that could be reached. He did not want in any way to disfigure the Castle, but he thought such a scheme would provide a great deal of work for the unemployed. In the end, the whole question was referred back to committee, and the Surveyor was asked to prepare plans to find out is such a scheme was practicable. At this same meeting, the Council discussed the Ministry of Health’s evacuation plans whereby the Town Clerk, Mr Stuart Peter, stated that a circular containing information on the subject had been sent out to every house in the borough. It was agreed on the recommendation of the Finance committee that Mr J. Dennis would be appointed the chief officer for the scheme, and that the borough would be divided into twelve areas.

Also on January 16th, the townspeople got to hear of the persecution that was being performed on the Jews in Germany. Speaking at the annual meeting of the Launceston auxiliary of the British Society for the Propagation of the Gospel Among Jews, Mr Ernest L. Lloyd, described the heart-rending treatment being handed out. “I do not hate Germany, for as a Christian one cannot hate them,” he said. “One feels a terrible sense of pity for them, although my own soul revolts against this terrible treatment of my own people. The whole Jewish problem is an excuse,” he declared. At the meeting, Ernest read out a letter his Society had received from one of the stricken Jews who was living in ‘No Mans Land’ on the borders of Poland. “I am hounded with 40,00 in ‘No Mans Land,’ he wrote. “500 of us are living in a room with accommodation for only 120, sleeping on straw…children die of typhoid like flies. Save me, please, save me. I wish only to getaway. Save one who is living in hell.” Remarking on the meetings at Launceston, Ernest said he had been inspired by the wonderful sympathy and attention given to his race. There were some places where he had to go and speak where he knew sympathies were against them. “Why is it that there was a Jewish situation at all today?” he asked. “Instinctively civilisation shrinks its shoulders at a Jew. Have we brought contempt on our own race by the way we have lived or served our generations? I do not think so. The only trade that the nations of the world allowed the Jew to do was money-lending or financing war. It takes more than a generation, it takes liberty and freedom to bring back to the Jew a new horizon and vista. He has not altogether brought on his own problems. Christianity has no race prejudice, but that ideal has not been lived up to and our race has been made the subject of ridicule. Jews live in communities, and that aggravates the Jewish problem.” He concluded by stating that four and a half million Jews were living in No Man’s Land and that no nation at all was able to help their plight. “Dark despair is facing the Jewish world today. If 70 million cannot compete with 500,000 Jews I have no respect for Germany. Why is there this problem? Any totalitarian state must have a scapegoat.” In reply, the Mayor, Alderman Herbert Hoskin, said for a long time they had been hearing and reading about the terrible plight of the Jewish people, and our hearts had gone out to them in their distress.

Also in the January it was decided at the General Purposes Committee of Cornwall County Council was to have the air-raid wardens under the supervision of the police. Also at this meeting Mr. A. Browning Lyne, the chairman of the committee, said that he was convinced any risk of a gas attack in Cornwall in the event of war was absolutely negligible.

At the February meeting of the Town Council it was stated that Launceston’s A.R.P. personnel was practically at full strength with the 22 out of the 24 wardens required having taken and passed the necessary examinations and passed, but that more volunteers were needed to fill reserve ranks. Women drivers especially were required as drivers of ambulances. At that time only two had volunteered and the service needed no less than twelve, with a reserve of three. It was also stated that the First Aid party comprised an establishment of fifteen and a reserve of five. This number had already qualified. First aid posts, comprising six men, and thirty women, were also practically complete. Volunteers were still being sought for rescue parties and decontamination squad and at that moment there had been no enrolments. The council were still awaiting a visit from the County Architect with regard to premises. It was acknowledged that the council needed to find a headquarters for A.R.P. purposes and stores. Plans for the fitting of gas masks were to be put forward as soon as possible, with over 75% of the residents having already been fitted. The Borough was now divided into eight areas, instead of the original 12. The survey in regard to the evacuation plans had been completed and Mr Dennis was then in the process of collating the results of the 1,200 houses.

And so with the situation on the continent looking bleak after German troops marched into Czechoslovakia on March 15th, there was a reality dawning that the threat of war and its repercussions were a step closer, meaning a new effort was being made in preparation for war.

A meeting of local road operators was held at the end of March to form two groups for the Launceston area. Major W. J. Williams, chairman of the North Cornwall Association of Road Operators began by detailing the plans for petrol supplies during a time of emergency. He said that instead of waiting for the emergency to arise, as on previous occasions, they were trying to organise the country while they still had time. “You can readily see that Cornwall and the West of England will be vitally important in the time of war. This idea of road transport will be to feed the more vulnerable parts of the country,” he said. “This scheme is purely voluntary, but everyone present here to-night should place himself at the disposal of his country.” “Fuel will be very vital and will have to be conserved for private enterprise and the ordinary distribution of goods. Petrol will be controlled and bought in licence, and will only be sold to those who are doing an important national service.” He then asked everyone to fill the Ministry of Transport form with which they had all been supplied, to enable each operator to join the group. The group for Launceston sub-district was divided into three areas – Launceston Borough and Rural; Bude-Stratton Urban and Rural; and Camelford Rural. One would be for vehicles up to 30 cwt, and the other for vehicles over that weight. The minimum for each group was to be twenty-five vehicles, but bigger groups were openly encouraged, as this would make it easier for centralising of petrol. On conclusion, the two groups were formed on a proposal by Mr T. Fulford and seconded by Mr W. Downing. The committee elected were; Heavy Vehicles – Messrs W. K. Walters (chairman and organiser), T. Fulford, G. Biddlecombe, jun, J. Maybee, R. Symons, F. Bright, W. Downing, W. C. Davey (Egloskerry), and R. J. Coombe (Altarnun). Light vehicles – Messrs F. L. Smith (chairman and organiser), E. Dylan, J. Wonnacott, W. G. Mooney, T. Chapman, C. Tolchard, A. Jerrad, J. G. Martyn (Egloskerry), S, Parsons, H. G. Egglese, and S. J. Petherick.

At another meeting also held at the end of March, Lady Vivian the Civil Defense Organiser for Cornwall, with responsibility for the Women’s Voluntary Service, gave an address where she explained the origin of the movement which had not reached Cornwall until the previous December when it was realised that there would be a large evacuation of children for ‘dangerous areas.’ Lady Vivian emphasised that the W.V.S. was an organisation that would assist the authorities, working under their direction and in close co-operation. She outlined that Cornwall was expected to receive something between 30,000 to 50,000 children and that a Care of Children’s Committee was being formed to aid the evacuation. She also emphasised that the Red Cross and St. John Ambulance organisations would be providing valuable assistance.

Local recruitment drives were also being held around the area with one held on March 27th at Stoke Climsland heralding 20 volunteers for the Territorials. Lifton company, Ambrosia, agreed that any employees of military age, who wished to join the Territorials, would receive full pay for the period spent training. In the April 1st edition of the Cornish and Devon Post, there was a call for conscription being made by Mark Patrick, M.P. for Tavistock, who was one of the signatories to a motion tabled in the House of Commons. The motion was “In view of the grave dangers by which Great Britain and the Empire are now threatened following upon the successive acts of aggression in Europe and increasing pressure on smaller States, this House is of opinion that these menaces can only successfully be met by the vigorous prosecution of the foreign policy recently outlined by the Foreign Secretary. It is further of opinion that for this task a National Government should be formed on the widest possible basis, and that such a Government should be entrusted with full powers over the nation’s industry, wealth, and manpower, to enable this country to put forward its maximum military effort in the shortest possible time.” On March 29th Prime Minister Chamberlain announced that the Territorial Army would be doubled in size, but at the same time he told the House that “we have not by any means yet exhausted what can be done by voluntary service.”

Defending the Prime Minister’s agreement at Munich when speaking at the Oddfellows Hall, Launceston on March 31st, prospective National Conservative candidate for North Cornwall, Mr Edward Robin Whitehouse said, “Many people were saying that we ought to have ‘made a stand’ at Munich and that there would have been no fighting because Herr Hitler would have retired.” “Those people were trying to get the Government out of power at any price. Although they were advocating making such a stand, it was the very same people who were crying out for disarmament and were dead against the Government’s rearmament programme when it started.” He continued, “I want to tell you why I think that our course at Munich was right, the reason is this. If you accept the fact that the Treaty of Versailles was not suitable for modern times and agree that it was not wrong of Germany to have broken that treaty, then it follows that in each move she has made up to the time of Munich, she had a certain amount of right on her side. In the case of Czechoslovakia in September (1938) she was only after those Sudeten lands which contained the majority of German people. She was going to control any place where there was a majority of Germans. In actual fact we did not know Hitler was going further than that, and we had to give Hitler every opportunity of living in peace and friendliness, for which we had hoped at Munich. If we were going to fight we must have absolute moral right on our side.” He went on to say, “The position today has quite changed. Now we know we cannot trust Hitler. Before, we were hoping that there was some good in him. Now we know that he has given up the idea of looking after Germans wherever they may be, and will ruthlessly crush anyone who stands in his way.” Appealing for unity, Mr Whitehouse said that we must stand as a democracy first of all united behind the Government and then united to our friends. The Government then would be able to come to understanding with other countries who appreciate freedom. Turning to the future he said, “the situation was extraordinarily serious.” After Mussolini had made his speech, he expected some declaration from our country, stating that as far as we were concerned we would go so far, but no further. He finally appealed for his audience to support all the local organisations for voluntary service, but pray that there should be peace.

By mid-April, calls were put out by the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry asking for recruits with 115 required to complete the War Establishment and Training Cadre for the 4th/5th Battalion and an additional 630 to raise a new Territorial Battalion. Meanwhile, the Devonshire Regiment was seeking upwards of 200 men for the 6th Battalion. President Roosevelt at the same time sent out peace proposals to both Hitler and Mussolini asking if they would be willing to give assurances of non-aggression for at least ten years against thirty-one countries extending from Finland to Persia. In his overture, Roosevelt said “Plainly the world is moving towards the moment when this situation must end in catastrophe unless a more rational way of guiding events is found. You (Hitler and Mussolini) have repeatedly asserted that you and the (Italian and German) people have no desire for war. If this is true there need be no war.” The full proposal This was sarcastically rejected by Hitler at a speech he gave to the Reichstag on April 28th. Hitler’s response

The Government introduced the Compulsory Military Training Act on April 26th which was the UK’s first act of peacetime conscription and was intended to be temporary in nature, continuing for three years unless an Order in Council declared it was no longer necessary. The Act applied to males aged 20 and 21 years old who were to be called up for six months full-time military training and then transferred to the Reserve. Locally this act affected 104 local men although it was thought that there were at least 460 men eligible for the Territorial Army. On April 29th a detachment of the 4/5th D.C.L.I. (T.A.) put on a demonstration at the Drill Hall in Westgate Street where the workings of the Bren gun and anti-tank rifle were shown. Many people assembled at the public meeting which was addressed by Mr S. J. Fitze, Lieut. Com. A. M. Williams, and Major A. Bartlett, Adjutant of the 4/5th D.C.L.I. The speakers were introduced by Lieut. A. Holman Dunn, O.C. Launceston Detachment. Mr Fitze, himself a former serviceman, having served during the First World War issued a call to arms. “This appeal does not imply that war is imminent, but it does imply that in these troubled times our country should be able to play its part in the maintenance of world peace, which includes all that we mean by home defence.” Owing to the rapid march of science, the motor and the aeroplane, the world has shrunk considerably. It has become a neighbourhood, in which unhappily, the neighbours are not all friendly. In this state of affairs, national defence has acquired a wider outlook. It looks to assisting to maintain the world’s peace by co-operation with other nations. Young men who spend more time on sport than in the study of current events may not have come to appreciate this point of view, but doubtless, they will in time. If recruiting is not so brisk as it might be, it is not owning to want of patriotism, but owing probably to failure to realise that the maintenance of world peace is actually self-defence.” He said, continuing “If we want to defend hearth, home and country if we are concerned for the honour of Cornwall and its ancient capital, it behoves us to do our bit. This we can do by enlisting in the County Territorial Battalion. Launceston has 36 to date, and now that the Infantry is mechanised, there is plenty of room for men of a mechanical frame of mind.”

However, some employers were unhappy with the Act, especially those in the farming industry. At a meeting of the Launceston Branch of the Cornwall Farmer’s Union held on May 9th, many of the speakers stressed that it would take young men from the land at a time when they were needed most. Mr J. H. Paige said it was ridiculous for the Ministry of Agriculture to ask farmers to plough up their land, and for another Ministerial Department to take the young men off the land for military training, without the agriculturists having any say in the matter. He thought the Union should protest against the Bill. Another farmer, a father of a young man eligible for compulsory military training, emphasised that although it would mean that there would be a great deal less work done on his farm while his son was away training, he thought it was only right that all persons should play their part in the national life of the country.

At Truro on May 12th, a conference of all local Cornish authorities was held by Cornwall County Council in response to a request by the Ministry of Health for the purpose of expediting progress in arrangements to be made in the county for the reception of evacuees. A statement was presented outlining the numbers expected at each respective ‘detraining’ station. Launceston was listed as having 4,300 for Launceston borough and 1,000 for Launceston rural. At the meeting the representative for the Ministry of Health, Mr J. Topping said, that at the outset Cornwall was to be available for evacuees from London. Railway companies were responsible for evacuees up to the detraining point, and the Ministry of Transport would take them to the various villages. Payment for children and lodging allowances would be made through the Post Office, and the householders could go to the Post Office with a slip from the billeting officer, and get a weeks payment in advance for the children. Peopke merely lodged would have to be maintained, and the maintenance would be met at the outset by the Ministry of Labour, who would make grants for a short period of eight days. Mr E. F. Packer, of the Ministry of Transport, said, as far as Cornwall was concerned the Western National Omnibus Co. had undertaken to arrange with local operators of buses for such vehicles as might be necessary to convey the evacuees, from the detraining station. Lady Vivian reported that the W.V.S. had offers of 2,000 private cars for the transport of evacuees.

That very same week, the Minister for War, Mr Hore-Belisha, announced in the House of Commons the Reserve and Auxiliary Forces Bill, which would enable the call to the colours of a large number of Army and Naval Reservist for three months. This was to ensure a greater preparedness against a surprise attack. The Bill made provision protecting all the men called up for their reinstatement in their former occupation.

Even with all of the troubles brewing on the continent, the people of Launceston still strived to lead as normal a life as possible and the week commencing May 12th, the town held a Launceston Festival Week to promote the town. The festival was officially opened by Mayor Herbert Hoskin to a large crowd gathered at the foot of the Guildhall steps. On opening the week’s festivities, he said, “During the past twenty years Launceston has been developing, and it now possesses many building sites which are a great boon to the inhabitants. Hundreds of houses have been built, and Launceston has sent its inhabitants to the houses on the outskirts where they enjoy health, light, and sunshine. This has been all for the good of this ancient borough, and now our Chamber of Trade, at last, realises that it can no longer hide its light under a bushel.” He continued “they, too, have been trying to develop business as the town has developed in past years, and they feel the time has come when they must do a little flood-lighting and show to the inhabitants of the town and district and visitors to the town that they have something in their shops that is well worthy of their attention.” During the week a music festival with nearly 400 entries was held as well as the traditional ‘beating of the bounds.’ The week’s events were well supported and gave a welcome respite from international matters.

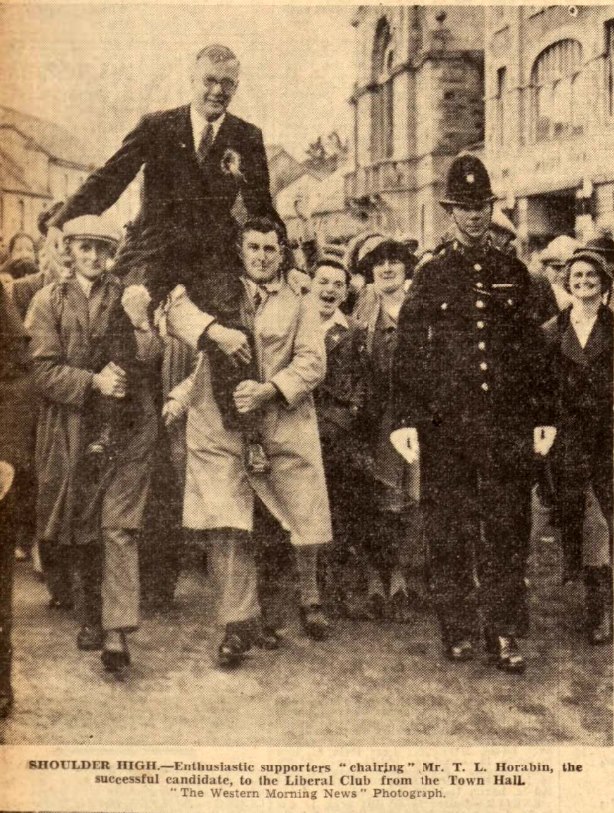

On June 9th the area was shocked when Sir Francis Dyke Acland, the M.P. for North Cornwall suddenly died, causing the need for a Bye-election. A hard fought campaign ensued, with the focus firmly being on the ensuing crisis in Europe. The contest was between the Liberal, Tom Horabin, and the Conservative, Edward Robin Whitehouse. Along with his party leader, Sir Archibald Sinclair, Horabin was a vocal opponent of Chamberlain’s Nazi appeasement policy. This issue was central to the debate in the by-election, which he won with an increased majority of 1,464 in a straight fight with the Conservatives. In a speech made in Launceston Square, Horabin suggested that the “Premier has done more harm than Hitler.” In his victory speech at Wadebridge, he continued his attack on Chamberlain when he said to his jubilant supporters. “This has not, in my opinion, been a fight between Horabin and Whitehouse, but a fight between democracy and the petty dictarship of Her Chamberlain.” “Democracy has won, and as soon as I have been round the constunency I am going to Westminster to fight for the mandate you have given me.”

A Government statement of July 5th was circulated to the Cornish and Devon Post, whereby it was advising people to store a weeks supply of food. In the statement, Mr W. S. Morrison, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster said, “Persons who have the means and facilities to do so might with advantage now provide a reserve of non-perishable foods in their own homes in addition to the stores which they usually keep.” Emergency supplies of canned meat, milk, and biscuit and chocolate were held by the Food (Defence Plans) Department sufficient for the maintenance for 45 hours of persons included in the official evacuation scheme, which will be issued by reception officers.

On July 17th, the Government announced a power rationing scheme applying to coal, coke, manufactured fuel, gas, and electricty, which would come into force in war time. After announcing the scheme Geoffrey Lloyd, Secretary for mines said that there would be no fear of a coal shortage, and there would be no queuing up for fuel. “In the last war large numbers of miners were allowed to join the Army and had to be brought back again in order to keep up the supply of coal, but this time that mistake will not be made,” he added.

Major F. Hare, Chief Constable of Cornwall, presented badges and certificates to over 200 local air-raid precautions (A.R.P.) officials at Launceston Cinema on July 31st. A procession of air-raid wardens for Launceston Borough and Launceston and Broadwood Rural Districts, Ambulance drivers, St. John Ambulance members, the Red Cross Nurses, Auxiliary Nurses, the Fire Brigade, and Auxiliary Fire Brigade, marched from the Ambulance Station to the Cinema, where the film “The Warning,” was shown. Major Hare was introduced my Councillor Sydney Fitze, who referred to the readiness of the people of Launceston to respond to the call of service. That had been demonstrated recently by the way men and women from every section of the community had answered the call of national need in the matter of air-raid precautions. “Some of us were impatient with the County Council for its slowness in waking up to the fact that it is necessary to organise for civil defence in Cornwall as it is in any other part of the country,” he said. “From the first, we in Launceston were very much alive to the need for preparedness, and I am glad to be able to report, thanks to the interest and zeal of those who have come forward as volunteers, that every section of our A.R.P. organisation is now in working order,” he concluded.

On August 23rd, when tripartite negotiations about a military alliance between France, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union stalled, the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact with Germany. With tensions rising on the continent, Air Raid Precaution activity in the local areas was greatly accelerated. Gas masks for the district were rapidly assembled, and in the Bude, Launceston, and Wadebridge districts distribution of the masks began on Friday, August 25th. Precautionary measures were taken locally including the removal of floodlights from the Southgate and the control centres being manned day and night. Over 4,000 masks had been assembled by the end of the 25th, with the work beginning in the Congregational Schoolroom (also used as the distribution centre for Launceston Borough), Northgate Street at 3:30 p.m. on the 23rd. On the 25th, A.R.P. officials in Launceston completed the assembly of a further 6,500 masks which were then distributed in the Launceston Rural Districts which were then distributed the following day. Residents in these rural areas were informed to make their collections between 2 p.m. and 9 p.m. from the following centres: Stoek Climsland, the Parish Hall; Lezant, Trekenner School; Lawhitton, the School; Noth Hill, North Hill and Coads Green Schools; Altarnun, Five Lanes and Bolventor Schools; Lewannick, the Parish Hall; South Petherwin, the Women’s Institute Hall; Tresmeer, Tremaine, and Laneast, Tresmeer School; Treneglos and Warbstow, Warbstow School; Boyton, Boyton School; Egloskerry, the School; St. Stephens Rural, St. Stephens School; St. Thomas Rural, Tregadillett School; Trewen, the Old Schoolroom, Pipers Pool. Over 95% of the 10,500 gas masks for the Borough and Rural district were distributed within forty-eight hours, with the remaining 5% being accounted for in the main by people being on vacation.

Residents were issued warnings to screen their lights and the various drapery shops saw increased business in the sale of dark material in the preceding weeks. Also well in place was the Launceston Evacuee Scheme under the control of Mr Percy Pearce. On the 25th August, every householder in Launceston was sent a letter concerning accommodation under the scheme with a view to details being brought up to date. The following officers were appointed for the scheme: Railway transport officer, Mr T. P. Fulford; marshalling offciers, Messrs A. W. Johns and R. H. Keast; food control officer, Mr R. Barriball; road transport officer, Mr S. G. Wooldridge. Each of these sectional officials was supported by other voluntary workers.

The Chief Warden for Launceston rural district was Mr B. S. Davey, of Hawk’s Tor View, North Hill, and the A.R.P. Officer for the area was Mr R. M. B. Parnall, of Launceston. Air Raid Wardens for the district, in alphabetical order, were: R. Alford, Trefursdon, Coads Green; W. Brent, Warren’s Park, Coads Green; E. Baker, Treniffle. Launceston; E. F. Brown, Berrio, North Hill; T. Brown, Tresmeer; J. W. Barber, Kings Head Hotel, Five Lanes; W. J. Billing, Trebullet; T. Banbury, Wolleaux, Laneast; F. L. Box, The Forge, Boyton; R. S. Bray, Newham Farm, Lawhitton; A. H. P. Clarke, Lidwell, Stoke Climsland; G. S. Congdon, Treguddick, South Petherwin; W. H. Coad, Trenault, Trewen; S. C. Colwill, Sutton Farm, Boyton; J. S. Cave, Tredaule, Altarnun; R. J. Chegwyn, Tober, Bolventor; J. C. B. Dingle, Stoke Village, Stoke Climsland; S. J. Doidge, Venterdon, Stoke Climsland; B. S. Davey, Hawks Tor View, North Hill; A. Edgell, Kennards House; P. D. Frayn, Egloskerry; W. H. Fry, West Curry, Boyton; G. T. Grigg, Trengune, Warbstow; M. J. Gimblett, Trelash, Warbstow; F. Gillbard, Trewinnow, Congdons Shop; H. Garland, The Village, Stoke Climsland; S. J. Hancock, Crinnick, South Petherwin; K. P. Kittow, Tredaule House, Altarnun; H. Landrey, Jubilee Cottage, Trebartha, North Hill; F. W. S. Morley, c/o The Rectory, Stoke Climsland; J. H. Martin, Athill, St. Stephens; W. Maddever, Treburley; F. C. Nickells, Tresmarrow, Launceston, A. T. Pearce, The Cottage, Polyphant; J. Palmer, Coads Green; T. Palmer, Home Park, Stoke Climsland; S. T. Perry, The Barton, Lawhitton; A. Pellow, North Down, Stoke Climsland; S. H. Parnell, West Park, Laneast; J. Pascoe, The Village, North Hill; S. Penhorwood, Conquarnel, Congdons Shop; C. J. Pratt, Post Office, Rezare; C. Prout, Rosendale, Canworthy Water; J. Prout, Trebeath, Egloskerry; W. J. Phillips, Church Town, Tresmeer; L. F. Rich, 6, Railway Terrace, Tresmeer; J. H. Sandercock, Trla, Boyton; G. E. B. Scott, The Vicarage, Lewannick; A. E. Symons, Lidwell, Stoke Climsland; C. L Symons, Trebartha, North Hill; A. Sloman, Carn House, Canworthy Water; G. Sandercock, Treween, Altarnun; F. E. Snook, Tremollett, Coads Green; W. C. Statton, Ferngrove, Warbstow; E. E. Taylor, Daws House, South Petherwin; W. J. Turner, 5, Railway Cottages, Tresmeer; J. Weeks, Egloskerry; J. H. Werring, Temperance Hotel, Lewannick; W. S. Werring, Venterdon, Stoke Climsland; A. Werring, Post Office, South Petherwin; S. Wilton, Church Walk South Petherwin.

Launceston was the designated Control centre for the most of North Cornwall, responsible for the Borough of Launceston, Launceston Rural, Bude-Stratton Urban, Stratton Rural, Camelford Rural, Broadwood Rural and Lifton (which it had taken over from Tavistock). The Control Room was situated in at the Congregational Schoolroom in Northgate Street and it had its own separate telephone lines connecting with nine telephones in the building. Of these telephones, the main one was installed in the Control Room itself, where, from calls received from district wardens and sub-stations, Air Raid Officials could trace activities across large-scaled maps fastened to the walls. Two telephones were devoted to receiving incoming messages, and two for out-going instructions to wardens and sub-stations. The other four telephones were to be found in the Service Room, and from here calls could be made to summon the Fire Brigade, Ambulance, Decontamination Squad or any general service. Direct lines were installed for Police and the Fire Service. Ditted around the main map in the Control Room, which roughly covered the whole of the West of England, were various coloured pins, linked to Launceston by coloured cotton, depicting the main report centres and sub-centres in and outside the area served by Launceston. Another large scale map of the Borough of Launceston enabled the officials to see at a glance the positions of the chief wardens and to whom to communicate in the case of damage within the borough boundaries. A store room was prepared for the immediate distribution of decontamination suits, etc. Hundreds of sand bags were also stacked outside to provide some protection against any attack.

A preliminary test for the wardens in Launceston reporting from the various sub-station was held on the evening of August 28th. The test, which involved the receiving of messages at the Control Room, and involved all the various services was considered “Highly satisfactory.” A further test was carried out the following evening. Also on the 28th, the Launceston Division of the St. John Ambulance Brigade staged a mock air-raid. The scene of operations was in a big wheat field at Landlake. Four civilians had been seriously “injured” in the raid and were lying in prostrate positions. Supt. R. Heard arranged for a call to be put through to the Ambulance Station, where several members were on duty. As soon as the call was received both motor ambulances were rushed to Landlake and members dealt with the “patients.” The Ambulance men had no difficulty in diagnosing the nature of injuries, as each “patient” bore a label stating the type of injury they were suffering from. They were dealt with accordingly and taken to the Ambulance Station in Westgate Street, which for the purpose of the exercise was considered to be a temporary hospital. The whole test was carried through within half an hour, and members carried out their respective duties with the utmost efficiency.

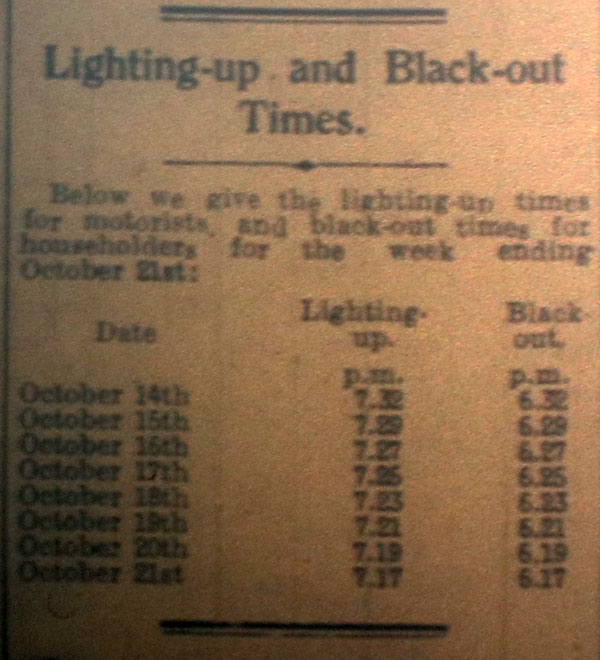

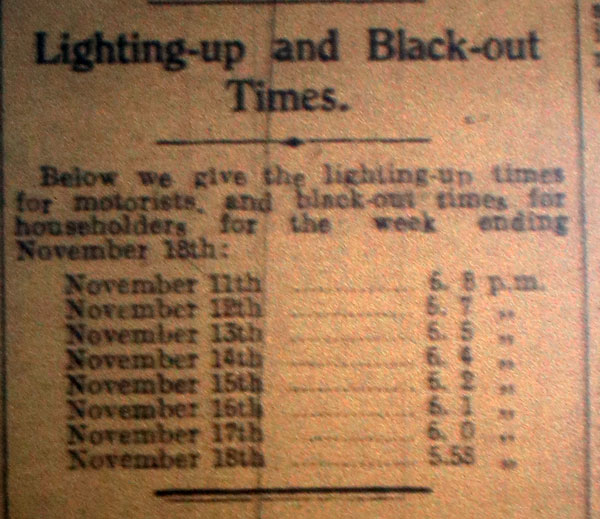

Other precautionary measures were implemented such as the white markings on pavements and roads for the benefit of motorists during “black out” when all lights are screened. The Home Office A.R.P. Department stated that all theatres, music-halls, cinema’s and other places of entertainment would be closed throughout the country during the initial stages of the war (this was soon lifted for most of the country by the second week of the war). This would be universal to start with, but it was contemplated within reason that it would be possible to permit places of entertainment to open in certain areas.

War, the outset of the ‘phony‘ one

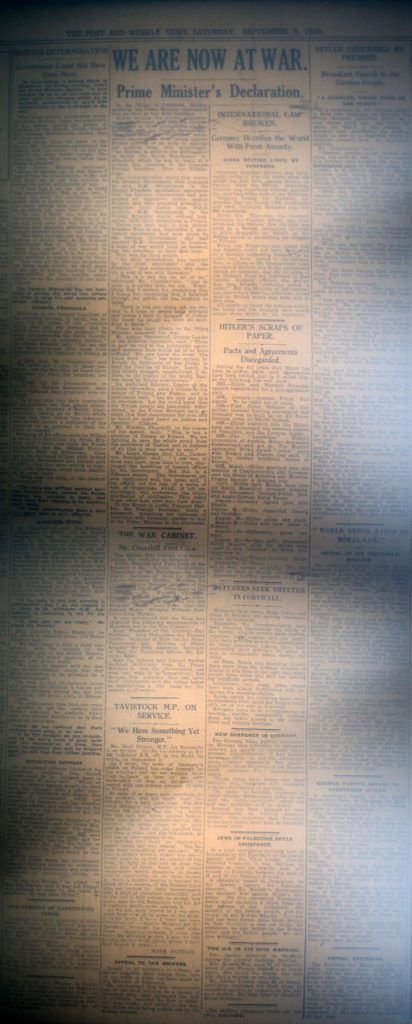

On September 1st, Germany invaded Poland after having staged several false flag border incidents as a pretext to initiate the attack. The United Kingdom responded with an ultimatum to Germany to cease military operations, and on September 3rd, after the ultimatum was ignored, France, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand declared war on Germany.

Immediately the evacuation plan was begun for schoolchildren and the priority classes.

Eldred Broad of Dutson Farm, remembers seeing a long line of railway trucks with armed guards beside them on the railway line between Wheal Martyn at Carthew (now the China Clay Museum) and St. Austell. On the following Sunday morning, as he sat on a stool in front of the open fire with the fountain and kettle, the only means of hot water (also the brandize for the saucepans), he heard Neville Chamberlain say we are now at war with Germany over the wireless.

We are at War, September 9th, 1939

Satisfactory blackout September 9th, 1939

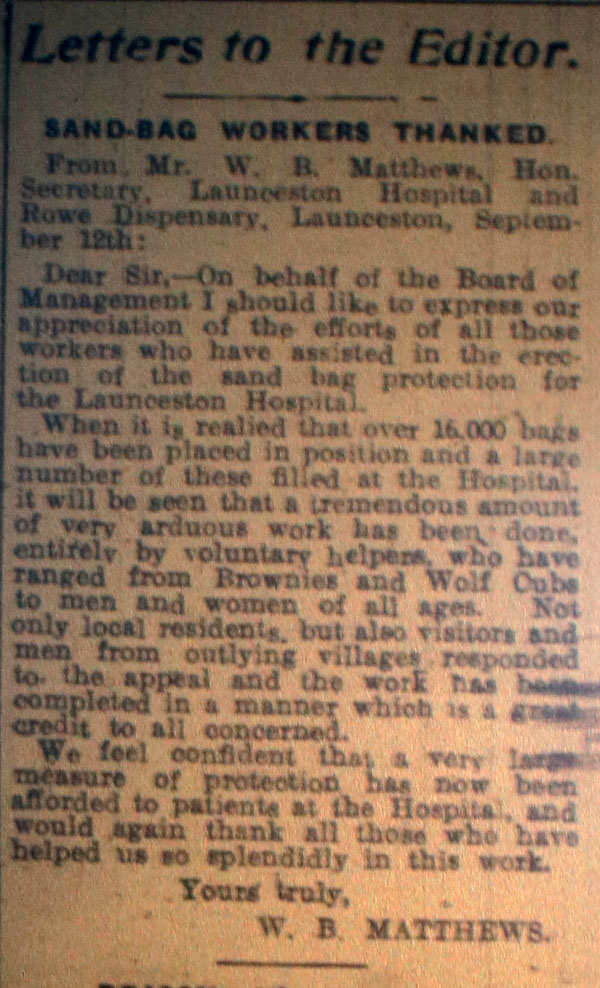

Launceston was soon a busy place. The first soldiers to arrive in Launceston during the war were billeted with local people, with the Tower Street Chapel Sunday School being used as the quartermaster stores and marquees being erected on the Castle Green for cooking and mess. The Defence Regulation No. 24 that came into effect on September 8th, had a Lighting Order that meant every night from sunset to sunrise all lights inside buildings must be obscured and lights outside buildings must be extinguished. Launceston Hospital prepared 20 beds for evacuated patients as well as over 16,000 sand bags being stacked outside the building. These were filled by volunteers which included school children, Girl Guides and Boy Scouts, members of the League of Hospital Helpers and many helpers from the surrounding parishes, particularly from South Petherwin and North Hill. At the Page’s Cross Institute (St. Mary’s Hospital) over 200 windows had to be fitted with dark black out curtains. From the announcement of the war, the Institute had to restrict the admission of all but acute cases, and reports had to be made daily to the headquarters at Truro of the number of vacant beds, and a daily record had to be maintained of the number of patients who could be sent home within twenty-four hours. Also at the Institute, extra beds were fitted in the children’s wards and in the day rooms. “Protective measures” included efficient sand-bagging of the hospital and other wards of the Institution, and casuals, and young and old men and women inmates worked until the night to complete bagging some 20,000 sand bags.

The earliest victim of the war locally was transport initially with the cancellation of a couple isolated bus services, but on September 11th, when the Southern Railway Company, announced that the district would only be served by eight trains per day – four up and four down. The National Coach bus Company, in addition to cancelling the summer service between Bude and Launceston, also suspended the Launceston town service. Petrol rationing began on Saturday September 16th under the Motor Fuel Rationing Order, 1939, and with this the heavy goods transport group had already met at the Constitutional Club on September 15th to discuss the impact of such measures would have on their operations. Here it was stated that although members had completed forms stating their agreement to being part of the group, a census form was also required for their district (sub-district H3) and sent to the Regional Transport Officer, Mr. H. R. Walters. Mr F. L. Smith, Chairman, stated that the rationing scheme for heavy goods vehicles, was based on the unladen weight of vehicles. The Group Organiser would then make a return to the Traffic Officer of his sub-district showing the number of vehicles available for work in the group. He warned that the work was well in hand and because of this it was to be understood that “unless the group was completed by the Group Organiser and returned, no petrol coupons could be given.” After dealing with the reservation of vehicles for defence work, Mr. Smith said that if anyone was unable to carry on his normal work it might be necessary at a latter date for individual traders to co-operate one with another. In order to facilitate the use of vehicles the Ministry of Transport would remove by order the restrictions imposed on A, B or C licences. The value of the petrol coupon was expressed in units and at the outset a unit represented one gallon of petrol, but with the value of a unit being possibly altered from time to time. Allowances per week were as follows: Unladen weight – Not exceeding 10 cwt, 3 units; 10 cwt to 1 ton, 6 units; 1 ton 11/2, 9 units; 11/2 ton to 2, 12 units; 2 tons to 21/2, 15 units; 21/2 tons to 3, 18 units; 3 tons to 4, 24 units; 4 tons to 5, 30 units; 5 tons to 6, 36 units; 6 tons to 7, 42 units. For each vehicle that drew a trailer and additional 6 units were allowed. All the coupons could be spent anywhere. For essential work one-sixth above the basic rations were allowed. Ration cards were not valid unless they bore the stamp of the Ministry of Transport and were valid for 14 days. Priority of petrol supply was as follows: 1. Production and distribution of essential food stuffs. 2. Conveyances of munitions. 3. Clearances of railway stations. 4. Urgent work for Government departments. Under a special licence issued by the Secretary for Mines, those engaged in agriculture were given special licence for motor spirit and Diesel oil during the harvest period.

One consequence of the war was unemployment which soared in just a couple of weeks as many trades were brought to a standstill.

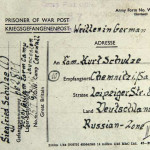

On September 22nd, the postmaster General announced that all correspondence and parcels for members of the services should be addressed “c/o Army Post Office,” and should not contain the name of any place or country. All addresses were to also to show: Army or Air Force number; rank and name; squadron, battery, company, or the section of the unit; Army or Air Force unit including in the latter case the letters R.A.F. It was also announced that no picture postcard or photographs would be allowed to be sent abroad.

At the meeting of the Cornwall County War Agricultural Executive Committee (North District) held at Launceston on September 26th, the new Ploughing-Up Order was explained. The extra quota allotted to the district was 9,000 acres, which were to be devoted to growing wheat, oats, barley, dredge, potatoes, and sugar-beet with the choice of the crop being left to the discretion of each individual farmer. For any land that had been down to grass for 7 years or more, a £2 per acre subsidy was available.

Eldred Broad recalls that in the early days of the war, free trade had been stopped and two men were appointed to estimate the deadweight of the sheep, but this caused a lot of discontents, before a weighbridge was installed, as it appeared that their friend’s sheep would always be heavier than other peoples.

The following day, September 27th, the Government introduced their first War Budget where Income Tax was raised from 5/6 to 7/- got 1939/40, and to 7/6 for 1940/41. Sugar, tobacco, beer, whisky and wines also had their duties raised. Sir John Simon, the Chancellor, forecast a probable expenditure for the year of £1,833,000,000. From taxation he would receive £995,000,000 leaving £938,000,000 to be met by borrowing. The first month saw an 8% increase in the price of food with sugar showing the biggest increase.

The call up of the first age group of men (20-22) began in early October, taking some 10,000 men out of agriculture. It was estimated that the Women’s Land Army, now 25,000 strong, would be able to replace the men. By the end of 1939 more than 1.5 million men had been conscripted to join the British armed forces. Of those, just over 1.1 million went to the British Army and the rest were split between the Royal Navy and the RAF. One of the first conscientious objectors from the district was a local farmer, Mr A. G. Stephens, who appealed to the South-Western Tribunal at Bristol on October 31st. He appealed on the ground that his conscience would not allow him to take up military service, as contrary to the teaching of Christ. Asked if he would be prepared to go so far as to grow food for troops, he said he was prepared to grow food if it were for the purpose of eating to live. The Women’s Land Army trainees were to later on in November gave a demonstration at The Manor Estate, Tetcott. Mr T. H. Dyer, councillor from Trelights, Port Isaac, acted as judge for the six girls who took part, who in turn displayed their abilities in: ploughing, spreading and carting manure, handling horses, milking, separating, scythe work, pulling mangolds, hedging, ringing and marking pigs, looking after poultry and pigs, cutting chaff, feeding stock, and all the other manifold of farming activities.

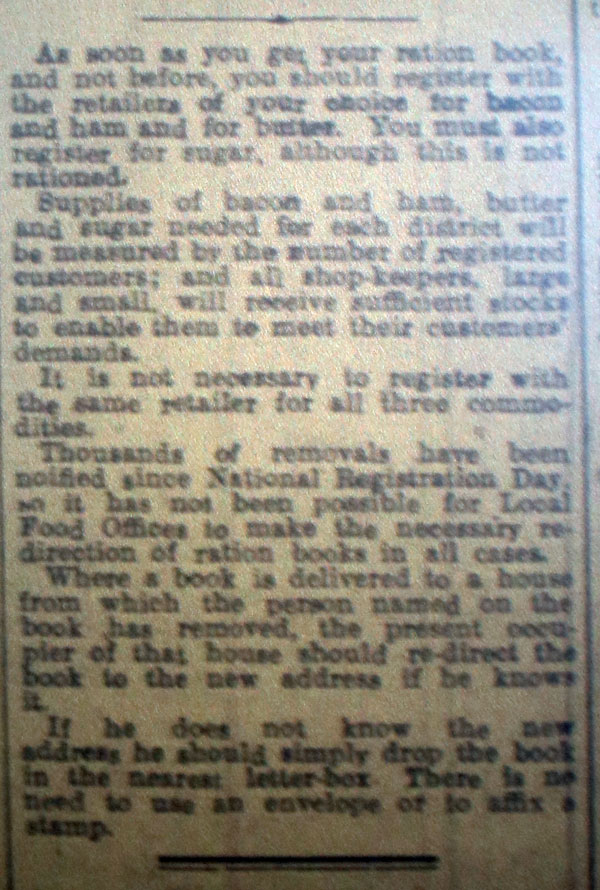

The rationing of bacon and butter began in December, with a limit of four ounces of each being permitted per person per week. The Government stated that there was no need for rationing for any other commodity for the time being, but did ask that the population restrict sugar consumption to 1lb per head per week.

Within the first two months, over 100 warnings were issued for black out offences in the town. Sidney George Adams, of 4, Chapple Terrace, was one of the first charged with failing to obscure a light so as to prevent any illumination there from being visible from outside the building. Sidney pleading ‘guilty’ wrote a letter to the Bench stating that he had never given any cause for a complaint before. The light visible at the time was not in the room concerned, but outside an open door, which was only open for four or five minutes. He was sorry to have caused any trouble. Sergeant R. H. Palmer in evidence said that at Chapple they had had great difficulty in tracing where the light came from. On this particular night the defendant admitted he was painting in that room and there was no special covering over the window. P.C. Colwill said that on October 25th, at 8 p.m., in company with Sergeant Palmer, he visited Chapple Park and saw a light burning in the bedroom window of No. 4. It was facing the town and was onubscured except for a thin curtain and the light could be seen for a considerable distance. Mr Adams was fined 7s. 6d. Another case was brought against Charles Edward Rawlings of 2, Mount Wise, who was charged of allowing a light to be displayed at the Cornwall Electric Power Co., showroom at Western Road on October 21st. The defendant admitted to the bench that “it was my fault; I clean forgot about it.” He was also fined 7s. 6d. Another defendant from St. Stephens after being warned on a previous occasion was also found guilty and fined a total of 14s. Further 7s. 6d. fines were issued the following month to William Locke of Southgate Street and to Herbert Edwards of Okehampton Road whilst at the same hearing, William Pearn, of 3, Belle Vue Cottages, and Charles Allen, of 2, Ridgegrove Cottages, both pleaded guilty to the charge of riding a pedal cycle on the road during the hours of darkness without a front white light. He was fined 5s. for the offence.

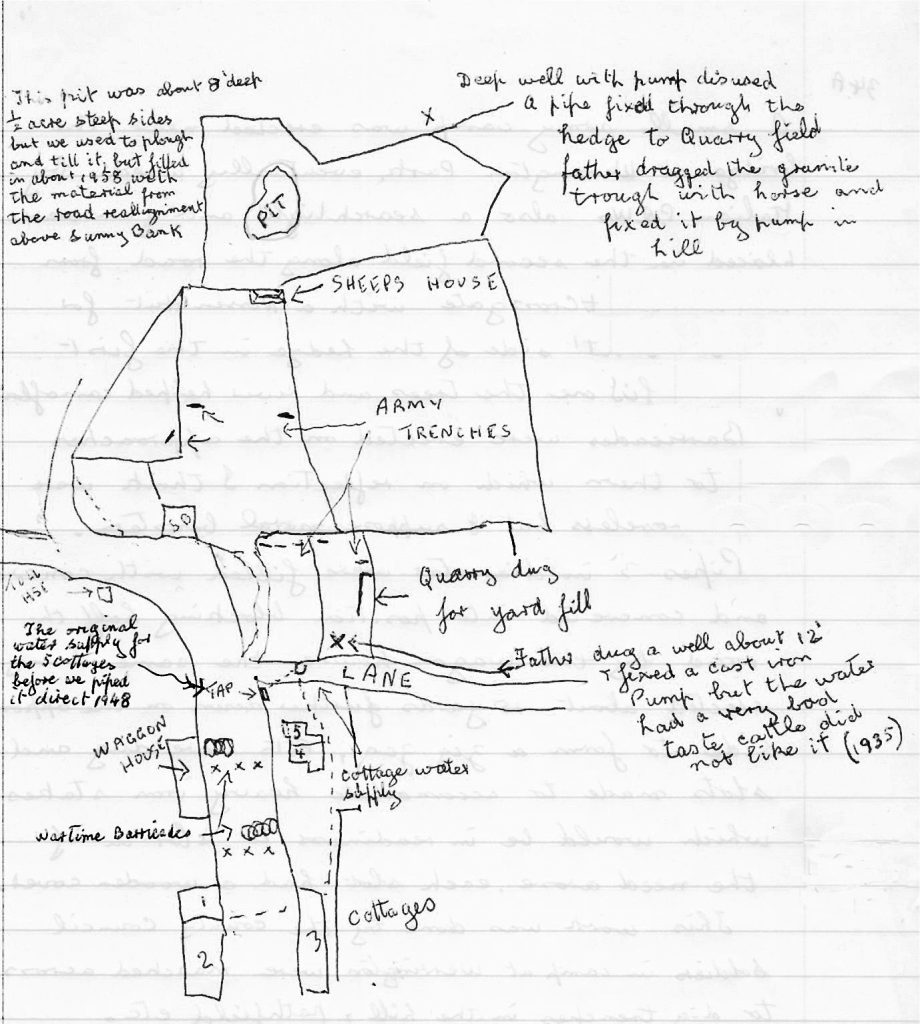

A small army camp was erected near the bridge at Werrington Park which was eventually used by Italian P.O.W.s. There was also a searchlight and gun placed in the second field along the road from Ham Mill to Crossgate with a Nissen Hut for the crew, this side of the hedge (from Dutson) in the first field.

Eldred Broad remembers barricades being erected on the approaches to the town “which on reflection I think were almost useless, but I suppose morale boosters. Pipes 3’ in diameter were filled with concrete and concreted into position blocking half the road by the wagon house. The same being erected about 15 yards further down on the opposite side to form a zig-zag. Pits were dug and slots made to accommodate heavy iron stakes which would be in readiness to slot in if the need arose, each slot had a wooden cover. This work was done by the County Council and soldiers in camp at Werrington were marched across to dig trenches in the hill, Pathfield etc. Also, half-round huts were erected at the lower end of Tree Field by Black American G.I.s, this was for ammunition storage before D-Day. American army lorries loaded with scores of Black soldiers from Hurdon camp, passed daily. Their task was to make an unloading and loading siding at Tower Hill Railway Station and erecting hundreds of these ammunition dumps, firstly digging a gap through the hedge and fixing the hut inside, and then when filled with ammunition each end was sheeted with a tarpaulin. From memory, I would think the huts were about 10’ wide and 12’ to 15’ long and about 10 to 15 yards apart, spread over many miles of roads around Tower Hill, wherever the road was wide enough for two vehicles to pass.”

Eldred also remembers “very early in the war, a plane landed in the big field at Netherbridge (26 acres at Tipple Cross). Somebody came running and said the Germans had landed, so Father and Uncle Frank took their shotguns to investigate. It turned out to be only a twin wing trainer that had run out of fuel.”

Eldred recalles the first evacuees were from the Balham area of London, and a Catholic School to boot. As such, they went to St. Josephs school which at the time was run by nuns. Our two boys were Smith (I can’t remember his first name), and Xavier de Valancie whose father was the French announcer for the broadcasts to the French people who were under German occupation. These two boys soon returned to London as did several others from the district as the bombing of London had not begun (1939-40 was known as the phoney war). We then later had Michael Marshall also from London, who was first billeted with Mr and Mrs Braunie Werren at Park Lanson but had to leave there because Mrs Werren was expecting.

With the evacuees arriving, there were seven or eight boys of my age in the village, with very few cars then we could really speed down the road with our ‘Gerry’s’. Not only were there few cars around, but petrol was also rationed and what was available, was only to be used for business reasons. I think the basic ration was 3 ½ gallons per month for a 10 h.p. car. Doctors, Vets, etc could obtain extra, but people who only used their vehicles for social trips had to lay up their cars for a few years.

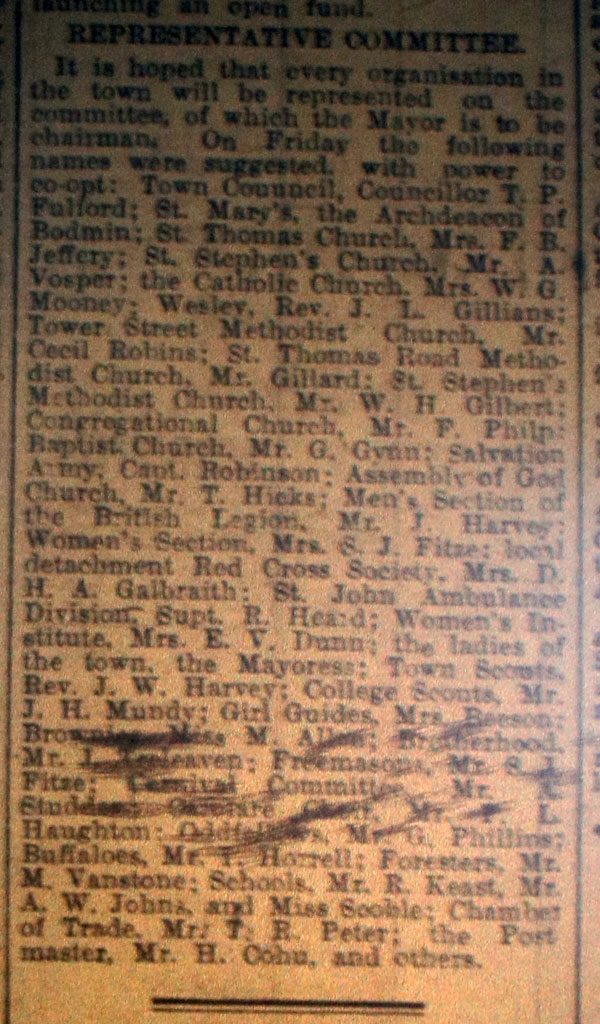

At a meeting held at the Oddfellows Hall in Western Road on Friday November 17th, the Mayor, Alderman Herbert Hoskin launched a fund with which to provide a parcel for Launceston men and women who were serving in the Forces. Among those present were clergy and ministers, representatives of the Town Council, both sections of the British Legion, Womens Institute, local detachment of the Red Cross Society, Scouts, and Launceston Brotherhood. Explaining the purpose of calling a meeting, the Mayor said that while he was serving in the last war he noticed that some of the men received parcels or a letter from an organisation with which they were connected, while others did not. He said “Although the gifts would be shared, there was always a feeling of disappointment in their hearts that nothing had been sent to them.” “We do not want that to be the case with Launceston,” he continued. “I thought the best thing to do would be to get a representative central committee from the town. I understand that the Brotherhood and the British Legion have schemes in hand, and probably the churches will be doing something. In my opinion it would be much better if we all co-operated and did something for every Launceston man and woman serving. If a Brotherhood man is serving, let there be a letter sent with our parcel from that organisation. If a member of a Church is serving, let there be a letter sent from the vicar or minister, and son on. If a man is not connected with any organisation, he would still get a parcel from the town and perhaps a letter from the Borough. We want to make them feel that we honour them for their courage, and this is one way in which we can show our appreciation.” Mr. P. Pearce who had agreed to become secretary of the committee, pointed out that the Brotherhood had already decided to raise a fund to send a reminder to Brotherhood members serving, and if any hardships should arise to help the dependants. After some considerable discussion, it was decided on the proposition of Mrs J. Harvey, seconded by Capt. Robinson, for the Salvation Army, that there be a house-to-house collection to get the fund started, and that each organisation do something to augment the fund later on.

At the November meeting of the Town Council, the clerk stated that he had received a letter from the County A.R.P. Controller, who wanted the Council’s views in regard to the suggestion that the local Control Centre be in future manned by voluntary helpers instead of two men and a woman paid officials. The Council expressed in their opinion that if the Centre was to be continuously manned day and night in an efficient manner it would be necessary to employ paid telephonists. However, the County Committee decided to cut down the personnel at the Centre, and that only one employee – a typist – should be paid. Thereafter from the last week of November, the Control Centre was only manned by a paid employee from 9 to 6 and the remaining hours were manned by voluntary help. An arrangement was made that from 11 o’clock onwards, any calls were transferred to one of the County Controller’s staff.

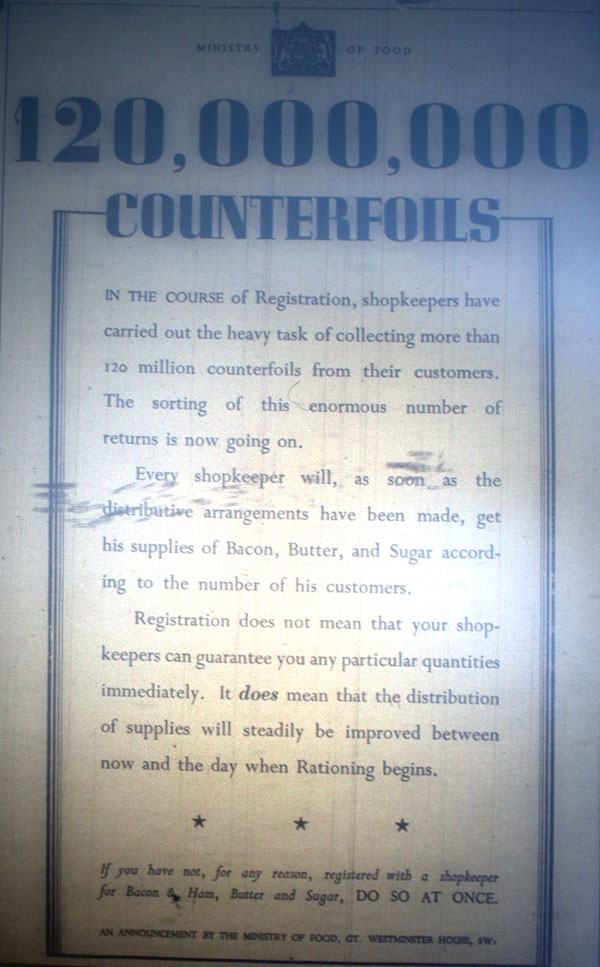

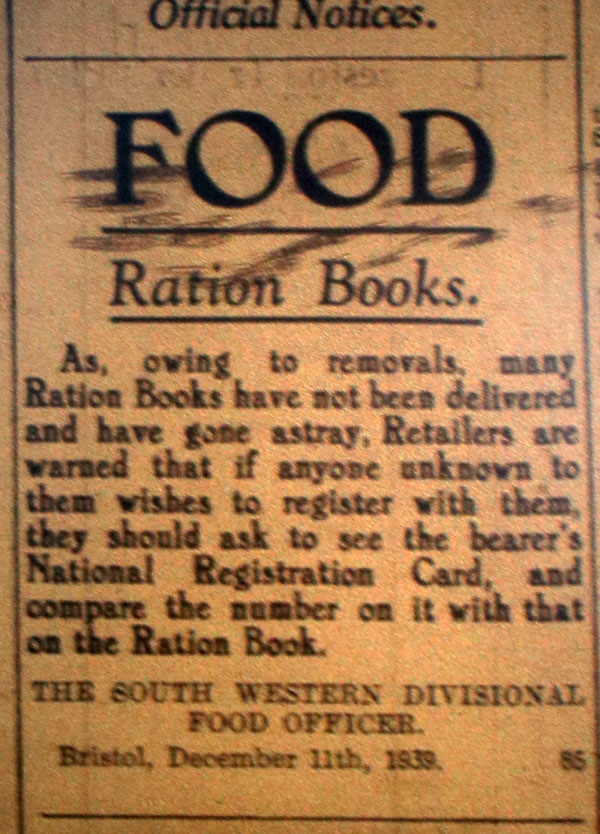

It was announced at the end of November by the Food Minister, Mr W. S. Morrison, that the rationing of bacon and butter would commence on January 8th, 1940. This restricted the ration of each commodity to 4 oz. per head per week. Although sugar was not then included in the scheme, consumers were asked to register with a retailer for sugar and to restrict their purchases to 1lb. per week per head. Boiled and tin hams would also come under rationing. So far as restaurants, cafes, and other catering establishments were concerned, the allowance of butter was to be on the basis of one-sixth of an ounce per head per meal served, and no coupons were required from customers for butter. Cooked bacon and ham was to be served only on the surrender of a half coupon or coupon in respect of a portion of about 11/2 oz. or 3 oz. respectively.

It was announced that men up to the age of 23 were to be called up with registration set for December 9th, 1939. It was estimated that this would provide a further 250,000 men for the services.

At the outset of war, the local fire brigade was augmented by the Auxiliary Fire Service, who rented garages at the Dockey, Race Hill and at St. Stephens. These were called respectively the Race Hill Patrol and St. Stephens Patrol. The Borough Fire Brigade and A.F.S. became part of the Fire Force 19 – Division E – Sub-Division 2 of the National Fire Service in 1941, and the captain William Miller’s rank was changed to that of Company Officer. The move to the Brigade being made part of the National Fire Service was due to non-standard equipment and procedures causing problems during the War when fire appliances and crews were mobilised outside their own areas to assist with the bombing raids of the blitz. Extra manpower were also recruited and the Launceston crews saw much action helping Plymouth during the blitz.

Launceston’s first air ‘attack.’

At 1:50 p.m. on Sunday, December 3rd, during a very bad thunderstorm of heavy driving rain and gale-force winds, the Launceston A.R.P. Control Centre received a ‘yellow‘ warning message followed at precisely 2 o’clock p.m., by a ‘red’ warning that indicated that enemy aircraft had been engaged near Plymouth. Then came the message that all in the town feared, “a single enemy ‘plane driven off from Plymouth approaches the town from the South.” Immediately the warning was communicated to all Services to stand by, and it was not long before there were unprecedented scenes in the streets of the town. The ‘plane had eluded its pursuers by taking refuge in the thick clouds and had swooped down to release its load of bombs so as to have a better chance of out-pacing the attacker. The Control Centre telephone rings again. A warden reports that a poison gas bomb had been dropped which fell 10 yards north of the pillar box at Badash Cross on Dunheved Road. A pedestrian walking to Church was injured by a splinter and became a victim of phosgene. A mustard gas bomb had fallen on the footpath on the west side of the College main entrance.

Within moments the decontamination Squad at the Municipal Offices received these instructions “Poison Gas Bomb at the College. Proceed around Pennygillam. Dunheved Road blocked.” With the final tightening of their gloves, fixing of masks and aprons, the Squad climbed aboard a lorry waiting outside the building. The men seated themselves on forms on either side of it, the space in the middle being used for the hoses, lime, brushes, picks and other equipment. It was an open lorry which offered little protection from the driving rain, and the driver was in a hurry to get to Dunheved Road as quickly as possible. On arriving at the scene of ‘destruction’ at Dunheved Road, the Squad soon erected yellow signs bearing the word ‘Danger’ in heavy black letters. Soon the now inflated yellow figures were to be seen mixing lime to neutralise the gas, while others were busy with the hoses washing away some sticky red substance, from where the bomb had fallen.

By now a second message had come in at the Control Centre, “A second raiding ‘plane approaches the town from the North… (A) High explosive bomb has fallen in the yard of Northumberland House, St. Stephens. One house (is) destroyed, (and) people (are) trapped, adjoining house was wrecked” Further messages poured into the Centre. The telephone bell was ringing continuously. “What’s that?” asked the telephonist, to make sure before committing it to writing. The warden at Newport replies. “A high explosive bomb, aimed at the Railway Station, has fallen outside Baskerville’s shop. The road is completely blocked by a crater six feet deep. All underground services are destroyed – water, gas and telephones – and there are seven casualties.” This ‘planes flight over the town had left a trail of wanton destruction. Another shattering message is received at Northgate Street. A third high explosive bomb had struck the roof of the Midland Bank, demolishing the building, which had caught fire. All in the building were killed, and there were twelve casualties in the Square. The warden in the Square reported to the Fire Brigade and Auxiliary Fire Service at the Fire Station (then by the Town Hall) that the Midland Bank was on fire. The Fire Brigade was soon on the scene, but on arrival, it was discovered that the fire was quickly spreading, and the Brigade had to send for the A.F.S., who brought the trailer pump, and it was not long before 12 jets were playing on the building. The Race Hill Patrol were also summoned to the Square, while the St. Stephen’s Patrol was occupied with the fire at Northumberland House. One of the firemen was badly ‘burned,’ and was rushed to Hospital by the fire patrol car.

The Rescue Party, whose headquarters were at Medland‘s Builders Yard at Chapple, were also busily engaged. They were travelling to St. Stephen’s in a lorry containing picks, shovels, and other equipment, when they found their services were also required at Newport. In total their were 22 ‘casualties’ in need of treatment and the Ambulance Brigade were kept very busy with private cars with slips bearing the word ‘ambulance‘ driven by volunteer women. The Mobile First Aid Post, stationed at the Drill Hall, was immediately put into use for those injured, with the badly injured being taken to the Hospital.

This was a picture of the havoc that could result from an actual air raid. Such a situation was not beyond possibility. These messages nor incidents, however, were not real, but part of an exercise prepared by the Town Clerk, Mr Stuart Peter, who was sub-Controller, to test the efficiency of the Launceston Borough A.R.P. Services. Weather wise, the exercise was carried out in terrible conditions, which drenched the members of the Scouts and Guides who were acting as casualties. Thunder and lightning added an extra spice for the rescuers. The siren was not allowed to be used to sound the alarm, so it was taken for granted that two o’clock should denote the time for activities to begin. General satisfaction was expressed at the way in which the duties were carried out, but it was felt there could be room for improvement in certain areas.

On December 24th, 1939, Launceston received news of its first casualty of the war when news of Alfred Winlove-Smith of ‘St. Merryn,’ Western Road, being one of the survivors from the mined Dublin tanker ‘Inverplane,’ reached his wife. It was reported that he was doing well in a hospital in the North of England. Alfred had been a reservist of the Mercantile Marine who was recalled to service at the outbreak of the war. He had originally joined up in 1911 and saw conservable service during the First World War when he was purser in a big Glasgow firm on board passenger and cargo ships travelling to South America. During that war, he survived being torpedoed.

The Ministry of Food announced that sugar rationing of 12 ozs. per week for each person would come into effect on January 8th, 1940. At the same announcement, it was also stated that meat would also be rationed, but a date was to be announced later, but every householder had to register with a retailer of their choice no later than Monday, January 8th. Mr Morrison, the Ministry of Food minister, also stated that the ministerial control of live-stock and home produced meat would be brought into operation on January 15th, 1940.

Carryin’ On! (September 30th, 1939) by Sal Tregenna.

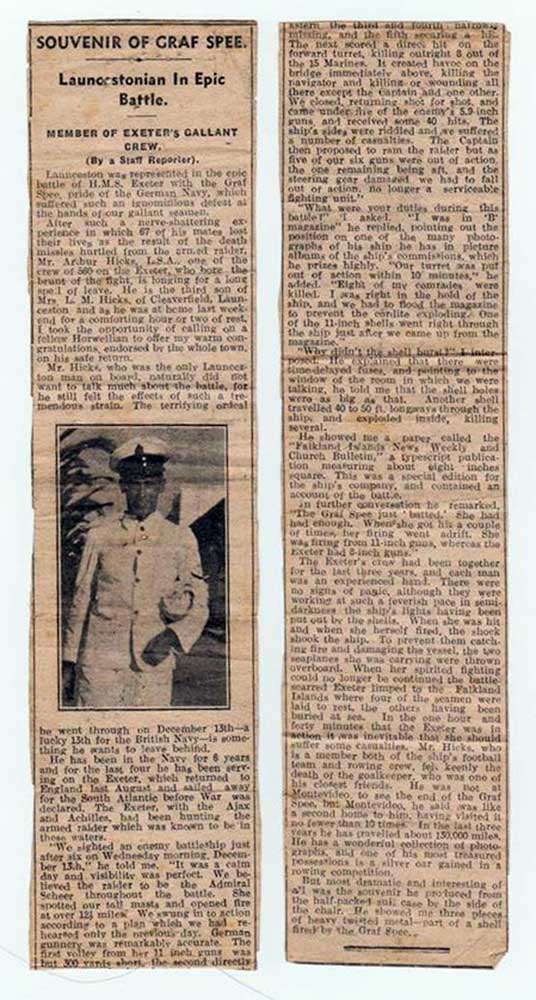

December also saw the Battle of the River Plate which was the first naval battle of the Second World War and for one Launceston man, Arthur Hicks of HMS Exeter, it was to leave an indelible mark on his life. The German panzerschiff Admiral Graf Spee had cruised into the South Atlantic a fortnight before the war began, and had been commerce raiding after receiving appropriate authorisation on September 26th, 1939. One of the hunting groups sent by the British Admiralty to search for Graf Spee, comprising three Royal Navy cruisers, HMS Exeter, Ajax and Achilles, found and engaged their quarry off the estuary of the River Plate close to the coast of Uruguay in South America.

In the ensuing battle, Exeter was severely damaged and forced to retire; Ajax and Achilles where another Launceston man, Mr Lethbridge, was serving aboard, suffered moderate damage. The damage to Admiral Graf Spee, although not extensive, was critical; her fuel system was crippled. Ajax and Achilles shadowed the German ship until she entered the port of Montevideo, the capital city of neutral Uruguay, to effect urgent repairs. After Graf Spee’s captain Hans Langsdorff was told that his stay could not be extended beyond 72 hours, he scuttled his damaged ship on December 17th, rather than face the overwhelmingly superior force that the British had led him to believe was awaiting his departure.

And so by the end of 1939, the die was cast with the evacuees well in place, rationing increasing, manpower being called up and the whole country now firmly on a war footing, it was with this that the country solemnly stepped into 1940.

Continue too:-

1940. 1941. 1942. 1943. 1944. 1945.

Link to Bert Tremain’s oral memory of his time with the DCLI during the Second World War.

Family at War L to R Ken, Ron, Ernest and Jack Hillman. Another of the family, Gerald, paid the ultimate price for his country when ‘HMS Anking,’ the ship that he was serving aboard was sunk by Japanese destroyers on the4th March 1942. Photo courtesy of Jean Harris

Launceston’s fallen from the Second World War.

Information sourced from Newspaper’s of the day including the Cornish and Devon Post, Western Morning News and Western Times plus from own account stories.

237 Air Raid Alerts in Launceston.

Altogether during the war, there were 237 alerts sounded in Launceston, and very few people ever forgot the effect on their nerves of the first wail at 12:30 a.m. on July 2nd, 1940. It was only of short duration. There were 17 in this month, some being during the hours of daylight (three in one day). The following month (August) there were nine alerts but it provided the longest so far, that on August 26th lasting from about 9:30 p.m. to just after 4 a.m. – about 6 1/2 hours. There were eight in September – three on one day. In October there was only one alert, and in November four; December, two; January, 1941 seven (the majority commencing round about 7 p.m.); February, six. The total for the month of March went up to fourteen. April 1941, was a trying month for C.D. personnel, when they were called to duty by the siren on no less than thirty-six occasions, in six cases twice in one day. It was during this month that Plymouth was attacked. May was also a heavy month with twenty-seven alerts, one of six hours and five of five hours. The number of alerts then dropped off; June, 13; July, 11; August, 5; September, 3; October, 2; November, 11; December, 7.

1942 – January, 1; February, 4; March, 3; April, 3; May, 1; June, 1; July, 1; August, 4; September, 3; October, 1;

1943 – January, 2; February, 9; March, 4; April, 1; May, 2; June, 2; July, 2; August, 1; September, 0; October, 0; November, 1; December, 0.

The following two years of the war saw very few alerts with just a couple being made in early 1944, but Germany’s ability to indiscriminately bomb the British mainland had been diminished to the point that Hitler had been reduced to using his wonder weapons, the V1 and V2 rockets, and these were targeted on the London and the South East.

Visits: 564

13th October 2019 @ 8:41 am

Fantastic amount of work gone into this. Will re-visit to read more. Thank you.

13th October 2019 @ 10:27 am

Thank you, glad that you like it.

18th November 2020 @ 6:08 pm

This is fascinating stuff. I’m writing a novel that touches on Launceston life at this period. Do you happen to know where the air raid shelters were in the lower bit of town around the stations?

12th December 2020 @ 2:17 pm

Hi Patrick,

I don’t I’m afraid. Due to secrecy at that time I have not been able as yet to find details on their location.

Roger

28th February 2021 @ 8:41 am

My dad and his twin sister were evacuated to Launceston. This is so interesting to see where they were.

22nd July 2022 @ 6:07 pm

A fascinating site; well done on all your work and effort to record this.

Particularly interested in the activities of the War Agricultural Executive Committee, and the National Farm Survey of 1941-43.