.

Before the significance of the symbols that are carved in Cornish granite and cover the outer faces of the walls of the Parish Church at Launceston can be rightly interpreted one needs to have studied the medieval history of England and of the capital of Cornwall as well as the science of Heraldry.

History illustrates how for four centuries after the Norman Conquest the government of England was often controlled by Anglo-French nobles and parts of a Church ruled from Rome who possessed large estates and obtained power and wealth by enslaving the bodies and consciences of the people; and it also sets forth before the influence of those foreign potentates began and continued to wane from the time when King John signed Magna Carta, and his son Richard, Earl of Cornwall, in conjunction with the Crown, signed Charters that granted municipal and commercial freedom to the inhabitants of the chief towns in each county so long as they acknowledged the king to be the supreme arbiter of English affairs, and paid an annual fee for their privileges. As to the science of Heraldry it grew up naturally out of the circumstances of the middle ages when comparatively few could read or write and symbols and pictures were employed instead of letters to educate the masses. Heraldry first found its special use in connection with military equipment’s. Men wore ensigns embroidered upon their outer garment’s and called them ‘Coats of Arms,’ and the same ensigns painted on their war shields and called them ‘Shields of Arms.’ Each genuine heraldic composition had its own definite and complete significance conveyed through as direct connection with some particular individual family, dignity, or office, and every such composition was a true legal possession and hereditary. By it genealogists are still able to trace pedigrees, and the growth of ‘Family Trees.’

In addition to their heraldic signs the individuality of each of the numerous medieval Church and corporations may also be traced by the architecture of their monasteries, churches, and castles, for although in their elevations and construction of their buildings all of them uniformly followed first the Anglo-Norman and then the Early English and Decorated styles, each community adopted a standard plan that differed in its arrangement from others.

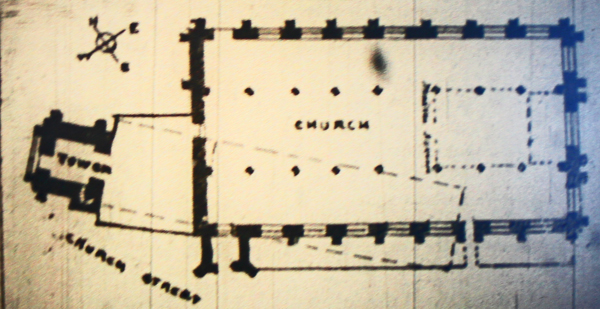

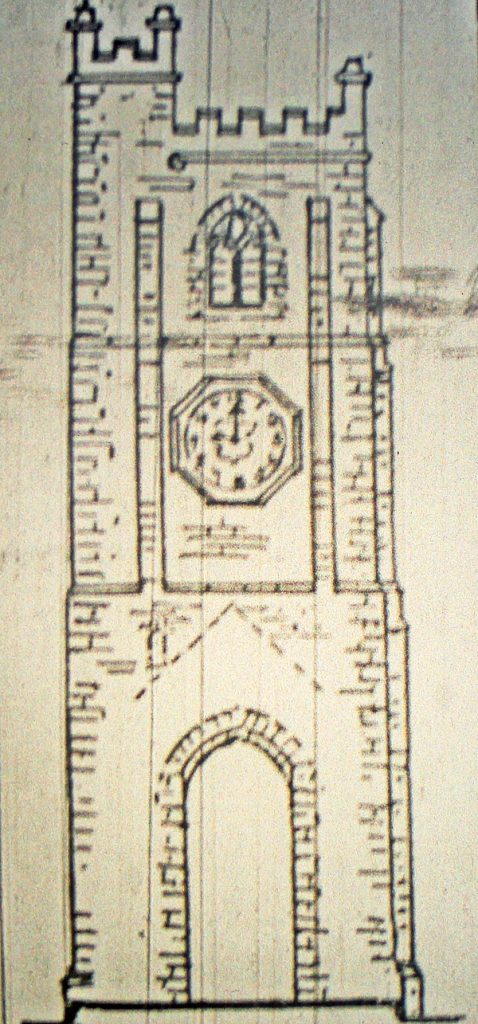

From A.D. 1066 on to the 16th century structures that were designed to be used for Church purposes only were aligned east and west, while those intended for the joint use of Civil and Ecclesiastical corporations were aligned south east and north west. For example, the standard plan of the Freeman’s Guildhalls at County towns was in the form of a parallelogram so arranged that a tower used for watching stores, and bell ringing, stood at the N.W. end from which a long aisleless hall of uniform width and height extended south eastward, a part of this hall next the tower being screened off and used as a civil Council Chamber, and the remainder as a Chapel. The Early English tower of the Guildhall at Dunheved is still standing, and over the high archway in its S.E. wall can be faintly seen the line of the contemporary hall roof. Refer to the plan of the Church and Tower which shows their relative positions and alignment, and also the probable extent of the original building.

When prior to the Reformation the area of one borough was united to that of another it was customary to append the name of the one attached to that of the other. There soon after the advent of the Tudor dynasty, or ‘New Monarchy,’ the borough of Dunheved became commonly known as Dunheved otherwise Launceston. Few representatives of the old nobles of England remained alive after the York and Lancaster wars, called the wars of ‘the two roses,’ ended in 1485, and during the reign of Henry VII (1485-1509) many estates they had owned passed back to the Crown by the law of attainder and were reconveyed to a ‘new aristocracy’ who cared more for personal liberty, commerce, knowledge, and science than for warfare and ecclalastical propaganda. The influence of the non-progressive Roman Catholic communities, who claimed most of the cultivated land in Cornwall until the dissolution of their monasteries, also rapidly weakened in this reign.

Henry VIII ascended the throne and married Katherine of Aragon in 1509. He had in his veins the blood of both York and Lancaster, and held undisputed possession of the Duchy of Cornwall and is reputed to have been hearty and affable, but monstrously wilful and selfish.

The famous companies of Cornish archers who used exceptionally strong bows, and arrows a yard in length, and were customarily mobilised and reviewed at the County town before passing on their way to join English armies between 1455 and 1485, had so hindered the inhabitants of Dunheved from repairing their homesteads that they were only just beginning to recover their pre-war conditions in 1510, when, to commemorate the crowning of Henry VIII, the Mayor and aldermen of the borough set in motion a scheme for rebuilding their dilapidated Chapel, and being unwilling to further tax the burgesses, wisely sought the aid of a wealthy Devon squire named Harry de Esse, who had recently married an Heiress, and settled on a neighbouring estate in Lezant parish previously owned by a very ancient Cornish family called Trecarell, whose title and coat of arms he, in accord with contemporary custom, had adopted. Harry Trecarell alias Esse was evidently one of those well educated, ambitious, and capable representatives of the new Tudor aristocracy who found their highest aspirations in honouring the king – upholding the supremacy on the Crown in both Church and State affairs – and in building and renovating local churches and chapels. He held high positions in the law courts of Devon and Cornwall, and the Bishop of Exeter (Hew Oldham) whose Sec included Cornwall, as well as the Duchy Sheriff (Richard Grenville of Stowell) and the aldermen of Dunheved, apparently gave him a free hand, when in 1510-11 he undertook to design and rebuild the Parish Church at the Cornish capital in accord with the new Perpendicular style of architecture that had been introduced in the days of Henry VII, and the standard plan of the Duchy guild of Freemasons. I think it probable that the walls of the original joint council chamber and Chapel hall had not extended further eastward from the tower than the site of the chancel door in the south elevation of the existing enlarged structure erected by Trecarell, and that one of the reasons why his design took more than thirteen years to complete was because the borough aldermen did not come to terms until 1522 with the owners of land required for extensions, who happened to be the Roman Catholic community at Launceston Priory.

The external walls of the Church founded in 1511, are faced throughout with squared blocks of granite, set in regular horizontal courses of varying depth; and that which distinguished the fabric from all other English Churches of the period is the historical series of heraldic and figure emblems that are sculptured on and cover facades. With the exception of the symbolical devices in the central bay of the east front and those over the south porch doorway, and the Latin inscription that begins at the chancel door, the emblems are heraldic. Each of the carvings has a hidden meaning, and the order in which they are arranged suggests that Trecarell was inspired by the story of ‘the writing on the wall of the king’s palace’ in the v chapter of the book of Daniel. They call attention to the vanity of mankind and the instability of mortal life, to the duty of the rich towards the poor and needy; and especially to the contemporary current of public opinion in regard to the supremacy of the Crown over ecclesiastical as well as State affairs in the realm. Considering the hardness of the stone and the close setting of the 15 inches wide panelling’s that run up perpendicularly to parapet and roof eaves, the sculptures are marvels of cost and cunning, and judging from their rough finish only one kind of tool, called a pick hammer, was used in fashioning them.

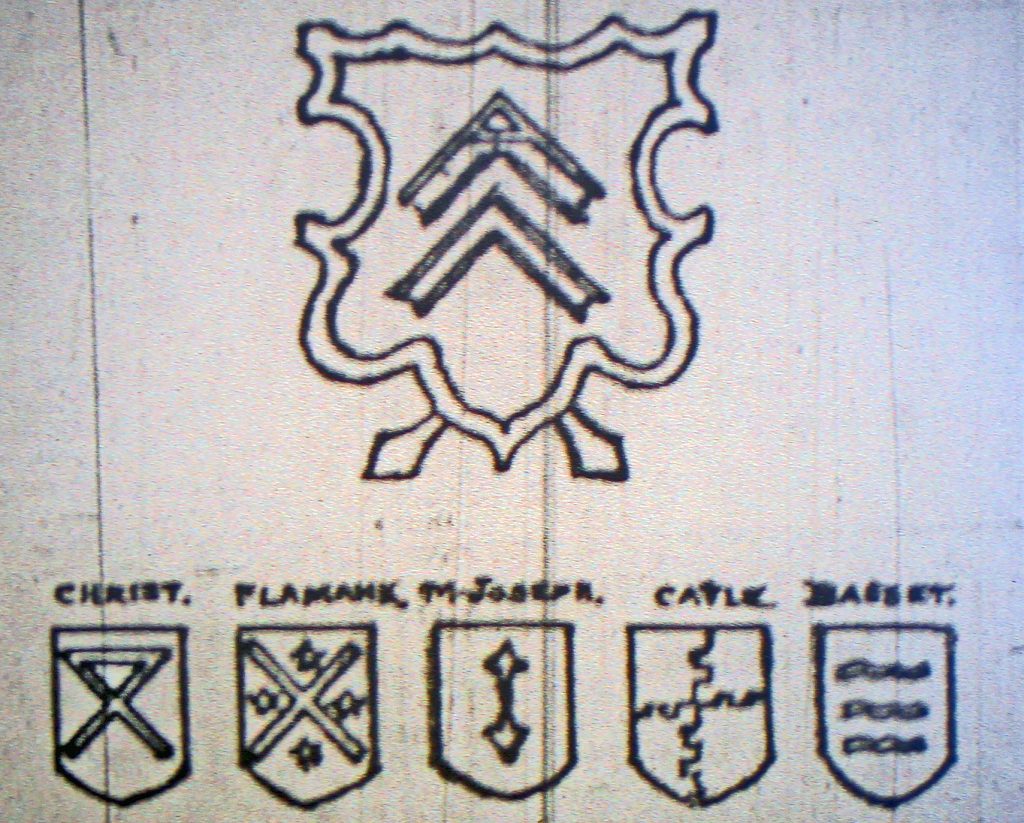

The effect and significance of the heraldic panels can be observed best on the east wall of the south porch where no openings intervene. On each of the horizontal courses one pattern continues to be followed all around the frontages, and the key of the grouping on each vertical panel represents ‘a family tree’ surmounted by a royal badge. The designs ascend in the following orders – In the space between the lower and higher plinth mouldings is a series of 235 quatrefoils each having in its centre a small shield and a four-leaved ornament alternately, except at the sides of some of the buttresses. Above the plinth, up to the level of the window sills, appears a course of panel tracery which has a small shield attached to each alternate mullion. It is on these shields that from the chancel door onward the letters of a Latin inscription are carved, each word being punctuated by a shield of arms. The biasons on these shields are for the most part borne by Trecarell and his wife, nee Kelway: But after the words meaning “The Lord be with Thee” appears a St. Andrew’s cross with the top limbs joined by a line called Jesue, which was one of the signs for Jesus Christ; and to emphasise words in the sentences “O how terrible and fearful is this place. Truly this is no other than the house of God and the gate of Heaven,” are depicted the arms of Sir John Basset of Tehidy, who was Sheriff of Cornwall in 1507, and also in 1522 when the east end of the Church was erected, viz, or, three bars uavy gules’ and the ensigns of three Cornishmen, two of whom were probably the leaders of the Cornish rebellion of 1497, the first showing argent a saltire between four fine painted stars gules, which occurs three times, borne by Thomas Flamank an attorney; the second two spear heads reversed and conjoined erect on iron worker’s badge, that possibly marked the forge of Michael Joseph an armour maker of Bodmin; and the third crenelee argent and sable the arms of the Cayle family who owned land called ‘Catherine parks,’ and other property at Launceston. Above the shield bearing tracery ascend four courses that form the heraldic tree pattern isolated examples of which appear on the face of each of the buttresses.

The lower courses of each tree show a two leaved seedling sprouted, anchored to a trinity of roots (ap root, and two suckers, with an acorn and a yew berry next the suckers to denote the unity of two families); the next course exhibits a large bordered shield suspended on the main stem, or trunk, and over this is depicted the top of the tree in full leaf. Above the trees comes a course bearing the royal badge of Queen Katherine, of Aragon, the pomegranate flowered seeded, slipped and leafed, and the Red and White Roses of Henry VIII, usually placed alternately. Upward from this the heraldic tree and royal badge patterns are repeated twice, no berries being carved on the second row of trees on the porch possibly to mark no issue when it was built. The third and last series is cut across by a projecting string course which continues all around the walls at the roof eaves line and bears a waving stem, with a trefoil leaf in the loop of each curve (emblems of ‘the ever flowing stream of Life’ and ‘the Trinity.‘) The panels finish on the east, north and western facades with the bordered shield design and on the creneliated south front parapet, end as they begin, with the two-leaved seedling. On the four frontages the family tree pattern (some being incomplete) is repeated nearly 200 times. At the corners of the east end the tree shields, which are elsewhere, for the most part blank, bear the Trecarell and Kelway arms, and at the same place, as well as over the north doorway on the line of the royal badges, are shields showing the arms of the bishop of Exeter’s See of Cornwall a chevronel between three bells of Dunheved borough, a triple reversed castle with a wavy line below to indicate the river Tamar. In various positions the arms of Trecarell, argent two ? sable, appear 37 times, and those of his wife Margaret nee Kelway, two bones in saltire sable between four ? ?, 27 times. The blazoning of the Trecarell coat on both large and small shield’s at the east end of the church displays a peculiar heraldic modification, the two bordering lines of the top chevronel being joined by ‘a feaze’ thus making the blazon a fease between the chevronel’s all ?humattes. This reading is confirmed by the Heralds College, and possibly indicates that the only son and heir of Trecarell had died when the eastern end was erected, the male lines of descent being thus cut short. A local tradition runs that one day the nurse in charge of this infant son left him alone for a few minutes and on her return found he had fallen into a tub full of water and been suffocated, seen by the Crown badges. The Red diamond shaped (see key pattern at east end of South Wall) and the White oblong square shaped, roses of Lancaster and York, borne by Henry VIII, are depicted 55 times, and the Tudor rose (some of the latter showing White roses in the centre), appear 17 times in the window arch spandrils. Tudor heraldic roses always have spikes between the petals, or on the stem. The ostrich feather badge of the Prince of Wales occurs 30 times. These feathers are erect and average 3ft. high, they act as supporters on each side of window and doorway openings and have the semblance of a scroll attached at the foot of the quills (see key pattern on the left of the south porch doorway). The pomegranate badge of Katherine of Aragon is repeated 112 times. Two flowers are attached to the stem of this badge above the first and second course of ‘family trees,’ but not on those above the string course on the south front. This Queen had given birth to two sons both of whom died while the church was being built. One born January 1st, 1510 died February 22nd following. The other born November 1514 lived but a short time.

Forming the finial of the hood mould over the central window on the east front is a complete representation of the coat of arms, and motto ‘Honi soit qui mal y perise,’ adopted by Henry VIII, in whose reign it was decreed that the arms of the ruling monarch should be displayed in every parish church. Shields bearing the arms of Dunheved borough occur five times and of bishop Oldham’s Sec of Cornwall six times. (For Devon he used the blazon a chevronel between three owls with three Tudor roses above). Over the north doorway in an arched niche is a representation of an extinguished torch, the symbol of departed life, and carvings in the spandrils of the arch somewhat resemble twisting reptiles. The figure subjects sculptured on the parvis wall over the South porch doorway include Edward IIIrd’s patron saint of England ‘Saint George‘ in armour, mounted on a charger, and aiming a spear at a dragon, the symbol of Evil. A man dressed in the garb of 1511 on horseback (probably intended to personate St. Martin of Tours) in the act of severing with his sword a cloak, one half of which he is offering to a cripple who limps after him on a crutch. There is also a representation of a man succouring another who has fallen by the way (The Good Samaritan), and of a man walking on the off side of a donkey and belabouring it with a stick (the Levite who passed by on the other side, at Luke, Chap, 10.32). A windmill, (corn had then to be ground at the manor lord’s mill and it was illegal to grind it in private houses), and of the gabled front of hall or mansion. Until a few years ago no effigy of the Magdalene occupied the canopied niche that divides these symbolical groups. At the base of the niche, on a shield quartering the Trecarell and Kelway arms, is a scroll upheld by two angels with the date 1511 in Roman numerals carved on it.

At the east end under the chancel window, in a 5 feet 6 inches long by 2 feet high recess, is a full length recumbent image of Mary Magdalene, the patron saint of the Church, resting her head on the right hand while with the left she keeps a book open. (The Bible was permitted to be read for the first time in English in the reign of Henry VIII). By her side is her emblem ‘a cruse of spikenard.’ On the background of the recess are spice leaves and shield bearing the arms of the Cornish See. Under and ascending on each side of the window above this image appear four and twenty surpliced choristers. The leaders wear capes with chains hanging over them, and carry flambeaux (the feast of Mary Magdalene was held at midnight). The musicians are shown as playing clarions, a harp, lute, rebec, bagpipe, and a hand organ. In 1509 bishop Oldham gave the clergy of Launceston permission to wear armlets, or capes, of grey for similar to those worn by the canons of Exeter Cathedral, during divine service and processionals. Superstitions concerning the figure of St. Mary (below) which lies outside and under the east window, state that whoever can, in one cast, cause a stone to lodge there will be rewarded with good luck.

On the top of the south porch buttresses appear two royal leopards holding shields, and surmounting buttresses on the east and south facades are eight bears similarly occupied (performing bears were commonly kept by nobles in the 16th century), and also the figure of an eagle with expanded wings (emblem of the As cenalon), of a pelican feeding her young with her blood (emblem of the Redeemer); and on the south front buttresses are eight urns. These latter are about 2 feet high and probably represent funeral vases and not, as has hitherto been suggested, the emblem of Magdalene, for the heraldic panelling’s on the south elevation all begin and end with two-leaved seedling courses and thus illustrate the ascent of mortality to death and immortality.

Carved on the ends of the hood mould over the window nearest the south porch, are two human heads, probably of the Mayor and chief Alderman of Dunheved in 1512, viz; John Bonaventure, whose badge is over the North door, and Henry Trecarell.

Internally both the nave and aisles of Launceston Church are 100 feet 6 inches long. The north and south aisles are both 15 feet 2 inches wide to the centre of the arcade columns and the nave 22 feet 5 inches, the total width being 53 feet. There was a striking similarity in Church architecture throughout the Duchy during the Perpendicular period. Two causes contributed to this, first the overweening influence of the wealthy monastic fraternities, and secondly the isolated position of the Principality which checked the current of diversified outside influences. Nave with chancel and aisles were almost always of uniform length as well as width, and sufficiently large to accommodate the inhabitants of each parish. There was almost a complete absence of the clerestory and chancel arches, and monolith granite columns, strung together by four-centred granite arches, divided the nave from aisles. That which distinguishes the plan at Launceston Church from others of the period, is the avoidance of a chancel ?vestry by making the fourth bay from the east end of the arches wider than the other bays and the roof loft stair turrets that nearly always appear, or appeared, before modern rebuilding’s, in either the north or south walls and sometimes in both, elsewhere. (The present choir screens were set up from 1903 on). The two centred instead of round arching of the roof ceiling timbers is also an unreal feature in Cornish churches.

Henry VIII divorced Katherine of Aragon in 1533, and in the same year Parliament passed two Acts. The first prohibited appeals to Rome, and the second forbade the clergy to pay to the Pope any longer an annual sum from the value of their livings. On August 25th, 1534, the prior and canons of the priory of St. Stephens, Launceston, signed an acknowledgment of the King’s supremacy. In 1535 the King was proclaimed supreme Head of the Church in England, and in the same year it was enacted “that St. Germans was to be asked and accepted for the See of the Bishop Suffrage in Cornwall.” Prior to 1535 the appointment of the Superiors of religious establishments had to be approved by the bishop of the diocese to which they stood. If an election was disputed an appeal could be made to the archbishop and finally to the King. After their appointment these Superiors nominated priests who officiated to parish churches within their purview, until the Dissolution of Monasteries. How Oldham, bishop of the joint See’s of Devon and Cornwall died in 1508, and was succeeded by John Voysey who nominated Thomas Vivian, prior of Black Canons at Bodmin from 1516 to 1533, vicar of Egloshayle, and prebendary of Endellion, to officiate at the rededication of Launceston parish church on June 25th, 1524. Cornwall was not constituted a separate diocese until 1576. The inscription that begins at the chancel door in the south front runs as follows – each Latin word being punctuated by a shield bearing a coat of arms-:

Ave (arms of Trecarell) Maria (arms of Kelway) gracie (Tre:) plena (Kel:) Translation : Hail Mary, full of grace.

Dominus (Tre:) tecum (symbol of Jesus Christ): The Lord be with thee.

Sponaus (Tre:) amat (Kel:) sponsam (Tre:): The husband loves the bride.

Maria (Tre:) optimam (Kel:) partem (Kel:) clergit (Tre:): Mary chose the best part.

O quam (arms of Flamank) terriballs (sign of Michael Joseph) Ac (Flamank) metiendus ~(Cayte) est (Tre:) locke (Flamank) iete (Basset): O how terrible and fearful is this place.

Vere (Tre:) aluad (Kel:) non (Tre:) ost (Kel:) hic (Basset) misi (Tre:) domus (Tre:) Del (Kel:) et (Tre:) porta (Kel:) celi (Tre:): Truly this is no other than the house of God and the gate of heaven.

A unique Church. The Meanings Signs and Badges on St. Mary Magdalene Church at Launceston. By Otho Peter, May, 1925.

Visits: 137