.

By Sir Alfred Robbins, 1885, with additional research marked * by Richard and Otho Peter.

Upon the threshold of the English Civil War, one of the causes of which was the King’s attempt to levy ship-money, a portion of which impost Launceston had to pay. Writing to the Council on April 19, 1639, Francis Godolphin, then Sheriff of Cornwall, stated that, upon receipt in the previous December of the writ for shipmoney, he imposed “a fit proportion” upon every parish and hundred, causing the constables to be the collectors. He was assured that no clergyman had cause to complain of being over-rated, and he had directed that “ no poor man should be rated unless he had an estate in lands or tenements worth 20s. or upwards by the year, or goods to the value of £10.” But everybody was not satisfied, for the Corporations of Callington, Camelford, and St. Mawes, in particular, “complained much of their poverty and disability, and desired to be relieved by other corporations,” and generally Godolphin found “no great willingness in the commonalty to pay,” and he expressed a fear lest he might be forced to make good some part of the assessment himself. In another letter of the same date he informs Nicholas that

a communication from the latter on the same subject, of March 11, had reached him on March 25 while at the Launceston Assizes, and be had not been able previously to reply because of the difficulties he had had over the ship-money. Although he took credit for himself that Cornwall had been the first county to send an instalment in answer to the writ, it was evident he was ill-satisfied with the success of his efforts, and he complained that only five towns had responded, Launceston with £30, Padstow with £25, Penryn with £18, Helston with £17, and Penzance with £10. He had threatened the other boroughs with pains and penalties if they did not soon pay, and he now asked for an order that any constables who did not recover the full sum assessed on their parishes should be sent for to the Council. The difficulties thus pictured by Godolphin were repeated and increased throughout the country, and Charles was forced in the spring of 1640 to call what is known in history as “The Short Parliament.” The members returned for Launceston were Sir Beville Grenville and Ambrose Manaton, while for Newport John Maynard and Nicholas Trefusis were elected. Of Grenville there is little to be mentioned between the date of Eliot’s death and that of his fourth return for Launceston. In 1636 his father, Sir Bernard Grenville, had died at Stowe, Kilkhampton, and in the next year Beville is to be found with. John Trefusis reporting to the Council that they had endeavoured to settle a municipal dispute at Bodmin but in vain.

In 1638 he raised a troop at his own expense with, which to assist Charles in the expedition against the Scots, showing in this the first sign of that devotion to the King which was afterwards to be his most distinguishing feature, but which, as exhibited by the tried friend of Eliot, has seemed a paradox not easily to be explained. In the summer of 1639, while still in the North with the King, he was knighted, and we find him writing from Newcastle in May of that year to William Morice, afterwards owner of Werrington and member for Newport, a prominent agent in bringing about the Restoration, and Secretary of State to Charles the Second. Grenville’s attachment to the royal cause may be differently looked at, but the most commonly accepted view is that taken by the sympathetic biographer already quoted, “that he saw sooner than most the bad designs that were forming, and apprehended very clearly the pernicious consequences which must follow from them.”

The Short Parliament was summoned to meet at Westminster on April 13, 1640, and was dissolved on May 6, but it was impossible for Charles to govern any longer without legal authority for taxation, and the Long Parliament was called. In this Grenville took his seat for the county, while Ambrose Mauaton (described in the

Official List of Members as Becorder of the borough) and William Coryton (who in the Short Parliament had sat for Grampound and who was now re-elected there) were chosen for Launceston, and John Maynard and Richard Edgcumbe for Newport. Of the four Maynard alone was devoted to the Puritan party, and he sat for Newport only a sufficient time to declare his preference for Totnes, for which place also he had been elected. It is to be noted, however, that there is some confusion among these returns. The Official List of Members, in addition to leaving Launceston altogether out of the boroughs represented in the Short Parliament, names Nicholas Trefusis as the only member for Newport; while for the Long Parliament it gives for the two boroughs the four mentioned above. But Browne Willis, whose authority has usually been accepted in these matters, names Grenville and Manaton for Launceston and Trefusis, Maynard, and Paul Speccott for Newport in the Short Parliament, and Manaton and Coryton for Launceston, and Richard Edgcumbe and Sir J. Percival, Knt., for Newport in the Long. At the first glimpse it would seem as if the Commons Journals would settle the point as to Maynard in favour of Browne Willis, for on April 17, 1640, in the Short Parliament, it is stated “Mr. Jo. Maynard chooses to serve for Totness, and waves Newport,” it appearing unlikely that Maynard would have been twice returned for the both boroughs after the distinct preference he had shown for the one; but this is upset by an entry of December 8, 1640, that “Mr. Maynard, chosen for Newport and Totnes, waves Newport, and chooses to serve for Totnes.” Although, however, a new writ was issued on the same day, it does not appear to have been acted upon, as on

February 9, 1647, an order was again made for a writ for Newport, “in the place of Mr. Maynard, who . . . chose to serve for Totnes.” The feelings of the majority of the Commons towards Coryton had been shown in the Short Parliament by the fact that in their order for a production of the proceedings in the Star Chamber and King’s Bench concerning several members of the previous House, with Eliot at their head, his name is not given though six of those implicated are set out at length. And the Long Parliament had not been in session many days before the vengeance of those who had not forgotten or forgiven his defection from Eliot began to be visited upon him. Acting as mayor of Bossiney he had, it was alleged, unduly interfered with the return of members; the matter came before the Committee of Privileges, with Maynard as chairman, the Commons instructing that inquiry should be made not only into the election at Bossiney but also into “the undue proceedings of the said Mr. Coryton, as Vice-Warden of the Stannaries, contrary to the Petition of Right.” In the next month it was ordered “that the Committee

for Mr. Corriton’s Business shall consider also of the Misdemeanours committed by Mr. Corryton, as Steward of the Duchy, and Deputy Lieutenant of the County;” and, after a long inquiry, it was resolved on August 18, 1641, “that Mr. Coryton shall not be admitted to sit as a Member in this Parliament,” it being furthermore agreed on the same day that a new writ should be issued “for electing of another Burgess to serve for the Town of Dunhevett, instead of Mr. Coryton.“; In his place, though the date of the election is not known, John Harris was returned.

The House of Commons at this period had, however, more serious work on its hands than the punishment of Coryton. Strafford was attainted at the end of April, 1641, Sir Beville Grenville opposing the step, and within a fortnight and before the execution, “Great Multitudes of People did repair to Westminster, being Full of Fears and Jealousies of Plots and Designs against the Parliament.” One outcome of the popular movement was a “protestation,” declaring attachment to the reformed religion and to the rights and liberties of the subject. Hundreds of Members signed on May 3, the day on which it was first laid on the table, among them and at the same time as Cromwell being Sir Ralph Hopton, afterwards the Royalist commander in Cornwall ; Piers Edgcumbe, member for Newport in

1627, and Richard Edgcumbe, member for Newport in the existing Parliament, it being doubtful which of these was the “Mr. Edgecomb” denounced by the populace as one of the “Straffordians, Betrayers of their Country“; and in addition there were John Maynard, member for Newport in 1640, who signed next to Denzil Holies, and Sir Alexander Carew, member for the county, whom Grenville had vainly besought to vote against the attainder. Signatures were added on several days during the next fortnight, but it was not until nearly every member who cared to affix his name had done so that, on the eighteenth, Ambrose Manaton, member for Launceston, followed the example, while Grenville, though not in the previously mentioned list of fifty or sixty Straffordians, did not sign at all. Two months later Parliament ordered that the whole nation should sign, and certificates preserved in the House of Lords show that the clergy, churchwardens, overseers, and constables of the parishes of St. Mary Magdalene, St. Thomas, St. Stephens, Lawhitton, and South Petherwin, as well as those of Tresmere, Trewen, and other places in the neighbourhood of Launceston, did in this matter as the Houses bade them.

The certificates referred to are mainly dated February or March, 1642, and in the January one of the clergymen who could have signed had passed away. The Register records that on January 6, 1642, (N.S.) “was buried Mr. Willm Crompton minr of Lanceston,” and it would appear that the reverend gentleman before coming to St. Mary Magdalene’s had been “ Preacher of the Word of God at Barnstaple, in Devon,” as well as at Little Kimble, Buckinghamshire, and Laneast, Cornwall, this information being mainly gathered from the title-pages of sermons he preached and published, principally in an endeavour to prove St. Augustine to have been the first Protestant. It is not probable that he had been long at Launceston when he died, (for “John son of Edward Gubbins minister” was buried here on May 3, 1636) but at all events sufficiently long to merit the honour of a special funeral sermon, preached by the vicar of Tavistock, and, with a dedication to the mayor, recorder, and aldermen of the borough, published in London, a copy being still to be seen in the Bodleian Library. Five years later, there was admitted to Merchant Taylors’ School “William Crompton, eldest son of William Crompton, clerk and Parson of Lanceston, co. Cornub., born at Little Kimble, co. Bucks, 13 Aug., 1633,” who afterwards became vicar of Cullompton, publishing some of his sermons as his father had done before him, and dying in 1696.

On May 30, 1642, when both sides id the great constitutional struggle were eagerly preparing for the war which was now felt to be imminent, John Escott, a Launceston woollen draper, was sufficiently incautious to condemn the proceedings of the Parliament in the hearing of Henry Willis, a townsman, who on the sixteenth of the next month deposed to the same before Nicholas Gennys, Mayor of Launceston, and Leonard Treise, Justice of the Peace. The affidavit was immediately forwarded to the House of Lords, which on the twenty-third ordered ” that John Escott, who hath spoken scandalous words against the Parliament, shall be sent for as a Delinquent.”* The unfortunate woollen draper was accused of having stated that ” he never knew nor heard of a Parliament that did

proceed so basely as this present Parliament now doth ; that many able honest Men of the House were grieved at their Proceedings; and that Mr. Seldon (who was a Man that had more Learning than a Thousand Round-headed Pyms)” had observed to an acquaintance that there was no good to be done in the House of Commons. Escott obeyed the order of the Lords, to whom, on July 11, he presented a petition stating that he had come two hundred miles to answer a false charge, and praying that the matter might be inquired into or that he might be discharged upon bail. The former portion of his prayer was granted, but in a manner little calculated to give satisfaction to the suppliant, as is evident from another petition he presented on October 9, in which he said that he had undergone part of their lordships’ sentence, having stood in the pillory in Cheapside and at Westminster, that he had lain in Newgate, where the sickness had been very hot for more than nine months, by which his health had been impaired, and that his estate had been consumed by excessive fees; he therefore prayed to have liberty on bail in London and within six miles round. Ten days later the Lords, “in regard the Plague is in Newgate, and he aged and sick,” granted his request ”for his health’s sake,” simply stipulating that he should “render himself within three days after notice given him from this House;” but it is not known whether he was further persecuted for

what would seem to us a legitimate effort of political criticism. What relation, if any, the sufferer was to Richard Escott, colleague of Eliot for Newport and of Grenville for Launceston, is also uncertain. From the Parish Register it appears that “John sonne of Richard Escotte” was christened on March 30, 1585, and on August 22, 1614, the baptism of “Richard sone of John Estcott” is recorded, here as in later instances the name of the latter (sometimes given as “John

Estcott, gent.”) being written unusually large. It may be thought that an individual once described as “gent,” could scarcely figure as a ” woollen draper” thirty years later, but as a careful distinction is made in the Register between “Mr. John Badcock mercer” or “Mr. Robt Pearse mercer,” and such other tradesmen as “John Abbot shopkeeper” or “William Cornish innholder,” it is evident that a superior social position was recognised in the case of the business with which the sufferer was connected.

While Escott was smarting under the sentence of the Lords, stirring events were occurring in his native town. The struggle between the King and the Houses became acute in the summer of 1642, and it was of the utmost importance to each side to secure the armed forces of the various counties. Cornwall was a doubtful shire,

and it was determined by both parties to make a trial of strength at the Launceston Summer Assize. The Royalists, who were welcomed into Cornwall by Sir Beville Grenville, had chosen Truro as their head-quarters, with Sir Ralph Hopton as their leader, while the Parliamentarians held the eastern part of the county, with Sir

Alexander Carew and Sir Richard Buller at their head and Launceston as their rallying point. The former had been invested by the King with a “commission of array,” upon the authority of which Hopton was levying troops, while the latter were endeavouring to raise the militia, the dispute concerning which had been the last factor in provoking the struggle. The Parliamentary Committee resolved to put the matter to the test of law, commencing proceedings by delivering to Mr. Justice Foster, the presiding judge at the Launceston Assizes, an order from the Lords and Commons inhibiting the execution of the commission of array, but when they required his performance of the same his lordship simply replied that “he would do his duty.” From the presence of the judge the members of the Committee proceeded to the church of St. Mary Magdalene’s, only to find the pulpit occupied by “one Mr. Nicholas Hatch,” whose assize sermon was a strong attack upon the policy of the Parliament; and on their return to the court matters were not much more to their satisfaction, for the judge in charging the grand jury “made a little

noise of the commands ” of the Houses, and only found “vigour, voice, and rhetoric” when upholding the royal instructions. Despite these discouragements, the Committee caused a presentment to be made “against divers men unknown, who were lately come armed into that county against the peace of the King,” but Hopton immediately produced in answer a commission to himself, signed by the Marquis of Hertford on Charles’ behalf. ” After a full and solemn debate “the grand jury acquitted Sir Ralph and his companions, and turned the tables by preferring an indictment against Carew, Buller, and the rest of the Parliamentary Committee” for a rout and unlawful assembly at Launceston, and for riots and misdemeanours committed against many of the King’s good subjects in taking their

liberties from them. The High Sheriff, John Grylls, was thereupon instructed by the grand jury “to raise the posse comitatus for the dispersing that unlawful assembly at Launceston, and for the apprehension of the rioters,” and as he was a Royalist he was nothing loth to obey.

All this did not take place without a wrangle in the court. The Parliamentary Committee told Sir Nicholas Slanning, one of Hopton’s colleagues and a member of Parliament, that the House required his presence, “but he answered with a politic silence,” while the Sheriff replied that he was a servant of the King, and “a sniffling answer” was all that could be obtained from our old acquaintance Coryton. After the grand jury had given its decision, both parties appealed to the townspeople. The day following the Assizes Slanning, Grenville, and many companions, together -with the Sheriff and his guard, went to the Launceston market-place and there read the royal proclamations explaining the differences between the King and the Houses, whereat, according to the Royalist account, “the people appeared well pleased.” But immediately the Parliamentary Committee heard what was being done they in their turn sallied into the market-place, and bade the Sheriff and his friends be silent, but these declined either to do that or to read the House’s commands, whereupon the Committee had to request their servant to

do the latter, and the strange scene ended in a wordy contest, and not, as might have been expected, in blows. The Royalists straightway went westward to recruit their forces, while the Commons’ Committee remained another two days in the town “labouring a right understanding of the power of Parliament and to undeceive the people,” and they then reported to the Speaker that their efforts had certainly been ” of high advantage.” (This account of the assize proceedings is drawn from three independent sources, namely, a long description in Clarendon (vi., 240 and foil.), a letter sent from Launceston by the Parliamentary Committee of the West to Speaker Lenthal (given in full in the Lords Journals, vol, v., p. 275,), and one from Beville Grenville and his companions (dated Launceston, August 5, 1642) to the Earl of Bath (summarised in the Fourth Report of the Historical Manuscripts Commission, Appendix, p. 307).)

For the time this did not appear to be the case. Hopton, following up the success he had legally gained, returned to Truro, and, having gathered a force of three thousand men, “advanced towards Launceston, where the committee had fortified, and from thence had sent messages of great contempt.” Sir George Chudleigh, a Parliamentarian, “being then at Tavistock with five or six full troops of horse,” drew to Lifton to assist his friends at Launceston, but his services were not required. “Sir Ralph Hopton marched within two miles of Launceston, where he refreshed his men, intending the next morning early to fall on the town; but Sir Richard Buller and his confederates, not daring to abide the storm, in great disorder quitted the town that night, and drew into Devonshire, and so towards Plymouth ; so that in the morning Sir Ralph Hopton found the gates of Launceston open, and entered without resistance.” The Royalists next moved towards Saltash, “where was a garrison of two hundred Scots, who, upon the approach of Sir Ralph Hopton, as kindly quit Saltash as the others had Launceston before.” The Parliamentarian forces were thus entirely driven out of the county, and as the Cornish Royalists would not advance beyond the borders of their own shire (a determination which ultimately proved the ruin of the King’s cause in these parts) they were disbanded “till a new provocation from the enemy should

put fresh vigour into that county, ”

Meanwhile the Houses had been taking steps to punish those who had been most prominent in opposing their Committee at the Launceston Assizes. On August 9, 1642, the Lords received from the Commons the letter previously quoted from, and forthwith agreed to resolutions adopted by the Lower House disabling Slanning from being a member and sending for him as a delinquent, the latter step being also ordered for “Mr. Hatch, the Minister that preached the Sermon,” and for the Sheriff of Cornwall, while Beville Grenville and John Arundell of Trerise (Trerice), both members, were summoned to attend the service of the House. In the letter already noted from Grenville and his friends it was prayed that they might have the King’s warrant not to leave their county except by his majesty’s orders. This request was evidently granted, for Grenville and Arundell replied to the order of the Commons that “they were commanded by his Majesty’s special Commands to continue in their County, to preserve the peace thereof,” and the Sheriff returned the same answer. The Commons thereupon resolved that Grenville should be disabled from continuing a member, and referred the case of the others to a special committee.

The winter which followed was a troubled one. According to journals favourable to the Parliament, the Cornish Cavaliers “like brethren in iniquity” were suffered by Hopton and Slanning to do as they liked, one of their exploits consisting in plundering the residence at Tavistock of John Maynard, the late Puritan member for Newport, for they “toare in pieces his writings, cut his beds in pieces, and cast abroad the feathers, and pulled down part of the roofe of his house.”

Comfort was, however, extracted by the Parliamentarians from a report that Hopton and his adherents in Devon and Cornwall “are in much distresse, having so lamentably plundred the Country, that it is unable any longer to sustaine them,” and from a later rumour that “Sir Ralph Hopton is either dead or dangerously sicke, and that Sir Bevil Greenvill and the rest of the malignants in Cornwall, are determined to breake up their army, being no longer able to continue them together for want of money and other provision.” A pamphlet, dated December 10 and entitled “A true Relation of the Present Estate of Cornwall,” contains a doleful picture of the troubles of the time. In this a certain Jeremiah Trivery denounced “the malitious malignant party, the Cavaliers of Cornwall,” who, having despoiled the inhabitants of Fowey at the end of the preceding month in return for hospitable entertainment, had proceeded for Launceston, where “getting in with the like wild they likewise plundered that, all but of their owne religion that are yet secure.”

January opened gloomily enough. Hopton, who had been besieging Exeter, learnt in the last days of December of the approach from Somersetshire of the Earl of Stamford with a large force, and he retreated by way of Torrington and Okehampton to Launceston. The Parliamentarians endeavoured to come up with him, and having on January 13 taken New Bridge after a smart engagement, occupied Launceston which the Royalists had abandoned. Ruthven, Governor of Plymouth, was the Parliamentarian leader in this enterprise, and was closely followed by the Earl of Stamford who came to Launceston “with a strong party of horse and foot.” The Royalists had retreated from Launceston to Bodmin and the Parliamentarians now advanced from the same town towards Liskeard. Battle was joined on January 19 at Bradock Down between Hopton and Ruthven, and the latter was so signally defeated that Grenville, writing on the same day to his wife (the Lady Grace Grenville who years before had been so much a friend of Eliot that he had called her his “sister“), felt the news to be so good that he told her that although “the messenger is paid, yet give him a shilling more.” Ruthven fled to Saltash, and Stamford, “receiving quick advertisement of this defeat, in great disorder retired (from Launceston) to Tavistock,” which he quitted upon the Royalist advance; and, Ruthven having again been beaten, a treaty was entered into between the combatants “whereby the peace of those two counties of Cornwall and Devon might be settled, and the war be removed into other parts.”

” The end of the treaty,” says Clarendon, ” was like that in other places.” Solemnly entered into in the February it was broken before the close of April. Each side had felt certain that this would be the case and had made preparation accordingly. In the April many gentlemen of Cornwall sent in their plate to the royal commissioners to assist the cause, and on the 29th an order was given from Launceston to Piers Edgcumbe and his fellows “to take into your hands what is to

be gotten beyond what is already come in and speed it to Sir Richard Vivyan.” A letter from the county, dated the 23rd of the same month and published in the Mercurius Aulicus, stated that the treaty had been broken off and that the war was likely to be renewed, and the prediction was soon verified. On April 25 the Parliamentarian forces entered Cornwall by way of Polson Bridge. “The night before the expiration of the treaty and cessation, James Chudleigh, the major-general of the rebels, brought a strong party of horse and foot within two miles of Launceston, the head quarter of the Cornish, and the very next morning, the cessation not being determined till after twelve of the clock in the night, marched upon the town, where they were not sufficiently provided for them. . . . Sir Ralph Hopton and Sir Bevil Greenvil (had) repaired to Launceston the day before the expiration of the treaty, to meet any attempt that should be made upon them . . . (but) all that was done the first day was, by the advantage of passes and lining of hedges, to keep the enemy in action till the other forces came up; which they seasonably did towards the evening ; and then the enemy, who received good loss in that day’s action, grew so heartless, that in the night they retired to Olungton (Okehampton), fifteen miles from the place of their skirmish.”

A more particular description of the day’s fighting, and one which shows more clearly the position of Launceston in regard to it, is given by Rushworth. He states that James Chudleigh, who was in command of the Parliamentarians, because of the Earl of Stamford being ill of the gout at Exeter, “having Intelligence, That the Town of Lanceston in Cornwall had but a slender Garison, no great Guns, and that their Ammunition was carrying away, etc., did enter Cornwall, beat the centinels Poison Bridge, and approached near to the Town, which is naturally well fortified with a Hill, called the Windmill, on and near which Sir Ralph Hopton’s Forces lay, having made a kind of Fort there. The Major gave them a Charge, but met with a more vigorous Resistance than he expected ; and niter several hours warm Dispute his Foot were forced to give ground, having no opportunity of bringing on his Horse to assist them, by reason of the many Hedges. Sir Ralph’s forces seeing them shrink, stoutly pusht on their Success, and sent a Regiment of Foot and three Troops of Horse to wheel about and fall on their Rear, and take Pulson Bridge behind them. But this was prevented by the coming in of some broken Companies of Colonel Mericks Regiment from Plymouth under the Conduct of Lieutenant- Colonel Calmady, and 100 of Colonel Northcot’s Regiment, under the Command of Sergeant-Major Fitch, who secured the Bridge, over which the Major Retreated, and brought off his Ordnance Ammunition and Carriages, without any extraordinary Loss, and lay that night at Lifton, and the next Day march’t to Okehampton, where they lay as in Garison.” This was the first blood shed in battle at Launceston from the time of Arundel’s rebellion close upon a hundred years before, but it was by no means to be the last.

*In the Parish Register is entered the burial of one “souldier” on the 2nd April, 1643. And in the sexton’s account against the Mayor are the entries :

24th April. Captayn James Bassett buryed in the Chancell. 25th. John Arundle, an Ensigne, in the Church. 4th May. Lewtenent Fitz-James in the Church. 30th. Henry Mynard, lieu, buryed. The burial of three “souldiers” is also recorded, and some of these entries are confirmed by the Parish Register.

On the 14th April Mr. Kingdon notes that Sir Bevill Grinfild came to towne with his regiment and had for the gard 2 seam wood 1 1/2 li candells. Aprell 17th. The Mayor charges for a gallon of sacke presented to Sr Ralphe Hopton, Sr Bevell Grenvell and others, 4s.; and, more, the 18th April to the law courte 2 quarts sacke 2s. 20th. Pd sending 3 malitia men by a pass into Devon that were scalded 6d. In the bill of disbursements of the Mayor are the following undated items:

Payd for a denner for Mr Coryton, Mr Mannington, Mr Powlle Spickkat (Paul Speccott) and others, wth a quart of sack the same denner 5s. 2d. Payd for a quart of sacke sent unto Mr. Basseat being in towne 14d. Item. I gave Killy for earring of a letter unto Ser Ralf Hopton 12d. Itm. I delyverd unto Mr. Bevell Escott in mach, powder, and bullats to the some of i5d. Itm. I delyved unto Mr Piper, maior, (of the succeeding year), on pown of powder for the King’s server 18d. Itm. Mor to Mr. Bevell Escott on pown of mich to keep sentanell 6d. Itm. Payd for making up of the walls be the dorer in the back lane by order of Capten Pendarvis 27s. (This has reference to the town wall adjoining Northgate on the east.) Item. For mysealf and Nobell to ride to Bodment to apear ther befor my Lord Mowen (Mohun), Ser Ralf Hopton, and other Commissioners, 10s. 22nd April. For 2 seame wood, 1 1/2 li candells ; and at midnight there was a larrum, and had more 4 li of candells. 23rd. They had for the gard 2 seam wood and 5 li of candells, being the day that the melecia was at Winmill. The Capt: of the gard had 2 seame wood to make bulletts. 24th. 2 seam wood, 2 li candells for the gard. At the same tyme ther wher 2 regiments in the Church, and had to buy wood, in mony 2s., and like had 2 li candells is. 13th May. Mr. Stokes notes “a warent to rayse horse, & the sending away of 2 warents for bringing in of provision.” On the 15th Oswald Cornish charges “for riding to Weeke wth provision for the Armye 4s. ; and Henry Bennett “for riden after the army with provisions 2 dayes 4s.”

Chudleigh, when he retreated upon Okehampton closely followed by Hopton’s forces, reported to the House of Commons that he had completely overthrown the

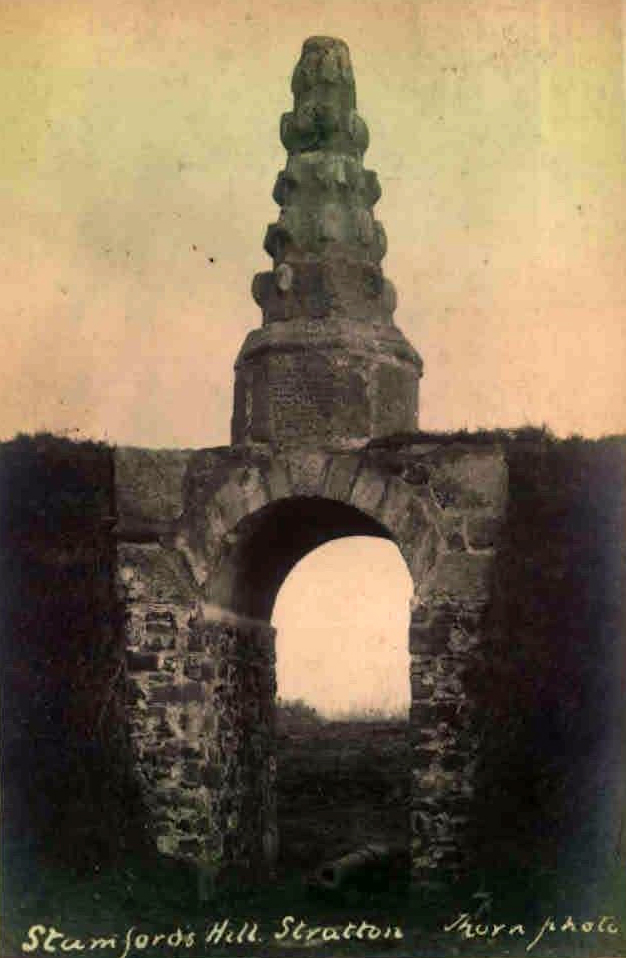

Cavaliers, but this statement was contemptuously disposed of by a Royalist newspaper, which observed that all that the Parliamentarians had done had been “to spend a little of their fury on the walls of Lanceston,” before forced by Hopton “to retreate backe to their owne quarters on the Edge of Devon.” But Chudleigh was nothing if not startling, and in his anxiety to astonish he was not above claiming for himself victories which he had not won. He now represented that in a fight in the early days of May with Hopton’ s men near Okehampton “the Lord sent Fire from heaven, so that the Cavaliers Powder in their Bandaliers, Flasks, and Muskets tooke fire, by which meanes they hurt, and slew each other, to the wonder and amazement of the Parliaments Forces,” it being added that this mystic fire “ so lamentably scorched and burnt many of their bodies, that they sent for 12 Chyrurgions from Launcestou to cure them.” The Earl of Stamford, having recovered from his gout, now took the Parliamentarian command in person, and his forces “being 5000 foote and 1000 horse marched into Cornewall,” and with this information was sent to London the same day a rumour that Hopton had died after a fight on Roborough Down. Stamford advanced upon Stratton, the only part of the count then well affected to the Houses, and detached Sir George Chudleigh to surprise Bodmin. Hopton and Grenville with the Royalist forces (which

were far inferior in numbers to the Parliamentarian) were at Launceston, whence they marched, as Clarendon says, “with a resolution to fight with the enemy upon any disadvantage of place or number.” The two bodies drew within a mile of each other on May 15, and on the next day was fought the battle of Stratton, in which the Parliamentarians (chiefly, as Stamford urged, through the treachery of some of his subordinates, and especially of James Chudleightt) were completely routed with heavy loss.

In a letter dated the day before the battle, a certain J. T. (who was probably none other than the Jeremiah Trivery) communicated to a Puritan friend in London a relation of “the places and Garrison towns of the Cornish Forces, with the number of souldiers therein.” In this he stated that the Royalist army lay at Liskeard, Saltash, Launceston, Bridgerule, Stratton, “and other Parishes neer the river.” “At Launceston M. Trevanian his Regiment is quartered, consisting of about 700 foot“; and in the list of officers appended to the letter occur some names which sound familiarly in Launceston ears. There is first “Sir Bevill Greenvile (Colonell of one Foot Regiment),” there is a Sergeant-Major Mannington and a Captain Mannington, a Captain Estcott, and two Captains Piper, one of these last-named not improbably being Hugh (afterwards Sir Hugh) Pyper, of whom much is later to be heard. In the same letter is a hesitating denial of the rumour of Hopton’s

death—a rumour which, with Chudleigh’s story of the thunder-and lightning victory, and the Parliamentarian defeat at Stratton, inspired Sir John Denham, a Royalist poet, to write ” A Western Wonder,” the opening verses of which may be quoted:

Do you not know, not a fortnight ago,

How they bragg’d of a western wonder?

When a hundred and ten slew five thousand men,

With the help of lightning and thunder?

There Hopton was slain, again and again.

Or else my author did lie ;

With a new thanksgiving, for the dead who are living,

To God, and his servant Chidleigh.

But now on which side was this miracle try’d,

I hope we at last are even ;

For Sir Ralph and his knaves are risen from their graves,

To cudgel the clowns of Devon

The Royalists lost no time in following up their victory. Sir William Waller (“William the Conqueror” as he was fondly called by the Parliamentarians) marched from London towards the West, and the Cornish forces, now joined by Prince Maurice, the Marquis of Hertford, and the Earl of Carnarvon, advanced from Stratton through Devonshire into Somersetshire, to meet him. After many skirmishes a battle was fought at Lansdowne, near Bath, on July 5, which with severe struggle the Royalists won, but their success was dearly bought. “That which would have clouded any victory,” observes Clarendon, ” and made the loss of others the less spoken of, was the death of Sir Bevil Greenvil.” “Bravely behaving himself ” said Sir John Hinton many years later in a memorial to Charles the Second, the old member for Launceston “was killed at the head of his stand of pikes,” within a fortnight of his friend of the Eliot days, John Hampden, having died from a wound received on Chalgrove Field.

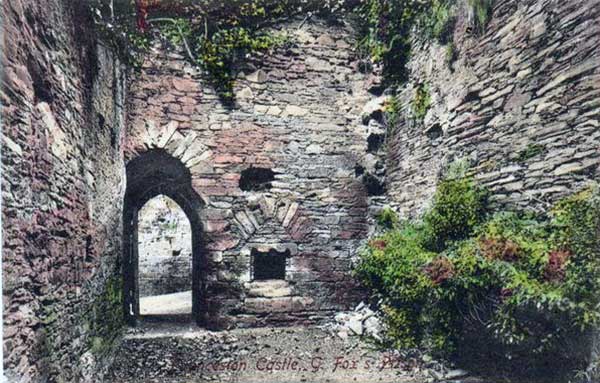

On endeavouring to form some conception of what Launceston was like in this period of wars and rumours of wars, let us picture a trooper of Rebellion days standing on the ramparts of the Castle. Not only the great natural objects—the Cornish tors, the Devonshire moors, and the valleys of the Tamar and the Kensey—but the church of the Magdalene at his feet, of St. Thomas in the hollow, of St. Stephen on the other hill, and of South Petherwin among the trees, as well as the South Gate with its Dark House above, would be as visible to him as to us. But the fort on Windmill, the North and the West Gates, plain then, have gone now;

and the Guildhall and the Gaol, the Bridewell and the Wall, St. Leonard’s Hospital and the Priory ruins, have similarly been swept from sight into remembrance.

And when we imagine our trooper descending from the keep and strolling into the town, the differences between the Launceston of two centuries ago and the Launceston of to-day become even more striking. Passing through the western archway of the Green, he would cross the draw-bridge over the castle dyke, a name not limited then as now to a portion of the old moat, and would proceed through Dockhay to the West Gate. By this he could go into the town, or, if he

chose, could climb the hill to the military post on Windmill, or skirt the wall under Mount Madford and enter by the South Gate. Through whichever portal ho passed he would soon find himself in Broad Street, a name familiar to him as to us and a thoroughfare then as now the business centre of the town. There before the Guildhall he would see the pillory, lately devoted to the sufferings of offenders against the Star Chamber and now being used for the punishment of words spoken against Crown or Parliament as either was for the moment uppermost, and he would read, if his culture had reached that unusual point, the latest proclamation of the King or the Houses according as Royalist or Roundhead then held the walls. As he glanced around his eyes would rest upon a dwelling, erected in the time

of Elizabeth and still in existence, and as he looked towards the West Gate he would observe some houses of refreshment the names of which have descended even to us. If he turned his steps towards St. Mary Magdalene’s, the carvings upon which had not yet lost their sharpness, he would take High Street or Church Street on his way, and in the latter would walk by the old shambles where the sale of meat was carried on, and beneath the overhanging stories of many a gabled residence, only one specimen of which remains. Passing the entrance to Blindhole, by which he might again have sought the South Gate, and turning from Fore Street, with the North Gate at its foot, he would by Castle Street gain the eastern gate of the Green, then surmounted by the residence of the Constable of the Castle.

And the portcullis, the grooves of which are still plain to view, having been raised, no enemy being near, he would pass Doomsdale (above) on the one hand and the old gaol on the other and again reach his quarters. It is probable, however, that although the Castle would be the scene of the trooper’s military life it would not be his abiding place by night, the sleeping-accommodation being of necessity limited, and he would, therefore, be billetted upon one of the inhabitants. The frequent changes in the occupation of the town from Royalist to Parliamentarian and from Parliamentarian to Royalist must have been a great embarrassment to those taverners who wished to keep upon good terms with the often-moved soldier-inmates of their houses. For the borough scarcely knew at any hour what force would command it the next. A drum-beat in the direction of Polson Bridge would announce the approach from Exeter of a tide of Royalists, and the road to Ridgegrove would be lined with spectators as these swept through the South Gate into the town. No sooner would they be settled into quarters than a hasty order from Hopton, borne at a gallop down Race Hill and through the same gateway, would call them away, and all the windows beyond the wall on that side the town would again be filled with gazers as the troops marched out towards Saltash. Shots from the Stratton side would next announce that hot work was being done in that quarter, and Fore Street would be filled as the Parliamentary forces with steady stride climbed St. Thomas Hill, and passing through the North Gate took possession of the Castle. And a day’s halt would be called, a Council of War held, and through Dockhay and by the road from the West Gate the Puritans would take their departure for Bodmin, there to yield to the Royalists or become masters of the West. The whole changing circumstances of this period are more like a dream than anything we can imagine as occurring in a sober far-from-the-world town like Launceston. We have seen in how many ways the borough was a participator in the events which

led to the great struggle, have noted the wrangle at the assize- court in which both parties, already armed for the encounter, professed their strict regard for the law, and have followed the course of Grenville and Hopton, Ruthven and Stamford as political dissension developed into civil war. There is yet to be unfolded a series of

scenes in which the clang of arms is again and again to be heard, amid the disputes of the Corporation ending in the expulsion of a Puritan alderman ; amid the visits of Essex, of Fairfax, and of Cromwell, of Charles the King and Charles Prince of Wales; and amid all the confusion of successive Royalist and Parliamentarian occupations of the town, with street-fighting in the streets and at the gates, with the Church despoiled of its lead for the casting of bullets and the Castle of its woodwork for the better embarrassment of the next besieger. It was not only in matters of warfare that Launceston was closely connected with the origin, the progress, and the outcome of the Great Rebellion. It was a centre of opposition to the King when taxation was first sought to be illegally imposed ; one of the country

—squires whose seats were within sight of the Castle, Richard Gedie of Trebursye, was father-in-law of the stoutest opponent of the loan, while two others, Nicholas Trefusis of Landue and Ambrose Manaton of Trecarrell, were joined in support of Eliot at the most critical period of the patriot’s career. And although Grenville and Manaton and Coryton, each member at some time for Launceston, fell away from the side they first adopted in public life, Leonard Treise of Tresmere, the borough’s Recorder, and Robert Bennett of Hexworthy and Thomas Gewen of Bradridge, two other of the neighbouring squires, were prominent in their devotion to the Parliament, the services of the first being rewarded by the Houses with a pension, those of the second being recognised by Cromwell appointing him to a seat in his Council of State, and the third proving himself so devoted to the Protector that he proposed the crown should be conferred upon him. And just as Bennett and Gewen, both members for Launceston, showed themselves staunch adherents of the Parliament, so Sir John Grenville, son of Beville, and Sir William Morice of Werrington, both members for Newport, approved themselves friends of the monarchy by being the principal intermediaries between Monk and Charles the Second

when the one was plotting to bring the other to the throne. The whole story of the Great Rebellion falls, in fact, within the period bounded by the first return for Newport of Sir John Eliot, earliest leader of the opposition against Charles the First, and the last return for the same borough of Sir William Morice, first Secretary of State to Charles the Second.

The completeness of the Royalist victory at Stratton, with its necessary consequence of freeing Cornwall from the Parliamentarian forces, might have been expected to have brought peace to the county for some time to come. But the departure of the King’s supporters to encounter Waller left the shire exposed to attack, and in August, 1643, “it is informe out of Devonshire, that the Inhabitants of Barnstable, Beddyford, and Terrington, in the North part of that County, are joyned in a body, and are gone into Cornwall, and that they intend to seize upon the houses, estates and goods of such of the Cornish Cavaliers as now besiege Excester”; but theso worthy gentlemen had speedily to retire ” without effecting much to their purpose, because the whole power of the County of Cornwall rose against them, so that their numbers being farre unequall to the Cornish strength, they were forced to give over their designe, and returne to their own homes againe.”

*The Launceston Borough Accounts contain no record of the battle, but they amply disclose the unsettled condition of the town. On the 22nd May, 1643, 2 warrants were issued for bringing in of horses, and on the 24th two more for bringing in of oxen. On the same day a messenger took a post letter to Bodmin, by order of Governor Pendarves. Many warrants were issued for raising money, and others without stating their purpose; but it may be inferred that some of them at least were for supply of army material, while messengers were also despatched to Callington, Liskeard, and Bodmin. The mayor for the year 1643, Arthur Piper, provided the

following arms for the town: “Six musketts at 10s. per muskett ; six payer bandeliers at 2s. per payre ; five corsletts at 1 3s. 4d. per corslett ; fower pikes at 3s. per

pike; eight pounds of gunpowder at 20d. per li, wch powder was delivered at an alaram heere by night.” Mr. Charles Kingdon charges 2s. 6d. “for ridinge to

Liskeard to informe Sr Ralph Hopton the Londoners were gone out of towne ;” and at another time “to inform him of the departure of the militia neere Camelford, 2s. 6d.” “George Jackson, ensigne, prayethe the worsl Arthur Piper, maior and captaine of this towne and St Steephens Company, to be allowed for himself and his horse on day at Kellington, at a mowster there, and staied all night, from thence to Saltashe too dayes on night 12s. Allsoe for a jorney att Bodman sissions last past too dayes and on night 7s.” Mr. Degory King claims 12d. “for a letter to Mr Recorder, for staying the towne band from goinge to Saltash;” and 4d. “for a note under Ser Ralfe Hopton’s and Sr Bevill Grenvile’s hands for the towne’s amuniton.”

Cornwall, therefore, remained true to the King, and Charles marked his sense of its devotion by a special letter of thanks, “given at our camp at Sudeley Castle, the 10th of September, 1643,” recognising to the full the zeal which had been displayed, “and commanding copies hereof to be printed and published, and one of them to be read in every church and chapel therein, and to be kept for ever as a record in the same ; that, as long as the history of these times and of this nation shall continue, the memory of how much that county hath merited, from us and our crown, may be derived with it to posterity.” A copy of this letter, painted on a wooden tablet, was placed and is still to be seen in most churches in Cornwall ; in Launceston it is in the vestry-room (which, until the erection of the new Guildhall, was the Council Chamber (1881)), and only a few years ago it was repaired and re-painted. Immediately the Parliamentarians knew what the King had done they protested against it, and declared that the letter would’ ” instead of being a Monument of Honour to that valiant Countrey in subsequent ages, remaine as a blemish and dishonour upon them, That they should be so seduced as to spend their strengths and lives and estates not in asserting their Liberties, and in defence of the King, joyned with his highest and best Councell the Parliament (as all good Patriots ought to doe) but in taking part with the King misled by evill Councellors who would (might they obtaine their wished ends) introduce popeiy and slavery upon them and the rest of the Kingdome, and will deserve no other Character than of being, The most infamous and industrious betrayers of the true Religion, and their owne Liberties.” The year ended without further fighting in the neighbourhood of Launceston, but it was a most fatal one for the inhabitants of the town. During its course the appalling total of 116 deaths, nearly double that of the highest number recorded for over a century, was filtered in the Parish Register. There were three in January, two in February, and three in March, and then there was a sudden leap to seventeen in April. In May there were twenty-three deaths, in June nineteen, in July sixteen, in August fifteen, and then another eighteen for the remaining four months of the year. That the war, in addition to being the cause of many of these by reason of the privations and alarms of the inhabitants, was the direct cause of several is shown by the number of soldiers buried in the town that year. The first was interred on March 22, another followed on April 2, “CaptainJames Bassett” on April 24, “John Arundle an Ensigne” on April 25, ” James Fithams Lieutnt ” on May 3, and “Henry Mynard a Lieutenant ” on May 30, besides three privates in May, one in June, one in July, and one in August ; while in the next year (in which there was a total of 42 deaths) ” Richard Jonas a souldier ” was buried on April 25, “John Millott a lieut ” on August 13, and “Alexander Winchborow a souldier ” on September 10.

*The Parish Register records the burial of a “souldier” on the 1st June, 1643, and of another on the 4th June. On the 22nd June ” Captaine Powlwhelle was buryed in the Church of St. Mary Magdalene.” On the 26th and 27th are charges for journeys with soldiers ” to be inrolled, including meat and beer for the men.” On July 3rd a warrant was issued for raising of horses. On the 4th another soldier was buried at St. Mary Magdalene.

The mention of these interments suggests the question whether all the soldiers who died or were slain in Launceston during the progress of the Rebellion were

buried in the churchyard. Rather more than twenty years since (1860), when the Castle Green was being made more level, many human bones were found a little below the surface, and it has been thought that these were of persons killed in the course of the Civil War or of prisoners who had died in the gaol. There may have been cases of both, seeing that the Register contains no reference to the death of prisoners for many years about this period, and in 1646, for instance, has no entry of a military funeral, though, as we shall afterwards see, at least two soldiers were killed here in that year. Early in 1644, the Commons determined to expel those members who could be accused of “deserting the service of the House, and being in the King’s quarters, and adhering to that party, ” and among those so dealt with were Manaton and Harris, members for Launceston, Piers Edgcumbe, a former member for Newport, and Richard Edgcumbe, the sitting member for that borough. Manaton and Piers Edgcumbe certainly, and the others probably, being deprived of their seats at Westminster, joined the “Mongrel Parliament” which met at Oxford, the head-quarters of the King on the very day of the expulsion, and on March 21 the honorary degree of D. C. L. was conferred upon the two former.

The siege of Plymouth by the Royalists was meanwhile proceeding, not without great difficulties in the way of the besiegers, one of which is shown in the record that the Cavaliers threatened to hang all those in the district who would not join their forces,”and having pressed six in Lifton Parish . . . they were compelled to send a guard with them to Exon.” But soon Launceston was again to bear the brunt of battle. The Earl of Essex, contrary as some assert to his own judgment, made a descent upon our county. On June 26, says Eushworth, the Earl “entered into Cornwall, Sir Richard Greenvile at Newbridge, the Passage into that County, maintaining an hot dispute for some time but at last the Parliaments Forces, with the loss of about forty or fifty Men gain’d the Pass and so passed on to Lanceston the Shire Town, where they took divers Barrels of Powder.” In a list of the Parliamentarian victories, published as a broadside in 1646 for popular circulation, this encounter is named as the one hundred and fifty-second success of the Puritan army, it being placed “in the moneth of June, 1644,” and described as “Launceston with four more final Garrisons taken by the E. of Essex, with al the ammunition.” While this was passing on the borders of Cornwall, Queen Henrietta Maria was in sore trouble at Exeter. “Here is the woefullest spectacle my eyes yet ever looked on,” said Sir Francis Bassett to his wife (writing at Exeter but directing his letter from Launceston after Essex had evacuated the town) ; ” the most worne and weake pitifull creature in ye world, the poore Queene, shifting for one hour’s liffe longer.” The Princess Henrietta had been born at Exeter on June 16, and, according to tradition, it was a Launcestonian who was of great help to her Majesty in her time of need. For “when the beautiful Queen, Henrietta Maria, was fearful for want of the rare thing—gold, she should bring a royal infant into the world with a state and ceremony as bare as its own nakedness, Sir Hugh Piper’s silver dishes, plates, caudle drinking- cups, and ladles, all went to the melting-pot, to furnish forth royal bedding and baby clothes, fees for wise women, possets for nurses, and spoons for godmothers and gossips, at the royal Exeter lying-in of the Queen.” According to the inscription to his memory in Launceston Church, Sir Hugh was born in 1611, and as this was one of the years during which the Register was imperfect it is not possible to tell from that source whether he was of Launceston birth, though there is not a doubt that he was of Launceston descent. The name of ” Hugh Piper, gent.” occurs in the Register in the earliest years of the century, both marriage and death being entered within the space of six months, thereby precluding the possibility of this being Sir Hugh’s father ; and the next entry of the name (which, were it not that the fact that Sir Hugh was at this time a Plymouth merchant prevents it from being a certainty, would appear to be that of the knight himself) is in 1641, when on “the 22th of August was bapt. Arthur the son of Hugh Piper gent.,” “Mary, wife of Hugh Piper gent.” being buried nine days later, and the child itself in November of the next year. But whether of Launceston birth or not, we shall find afterwards how closely connected with the town was he of whom it is stated on his monument that “he served in the Civil Wars as an Ensign, Lieutenant, and Captain, under Sr. Richard and Sr. Beville Granville, Knts., at the siege of Plymouth, at the battles of Stratton and Lansdowne, where he was wounded in the neck, thigh, and shot through the shoulder. His estates were sequestered by the Rump Parliament for his loyalty to his Master and injured Sovereign, King Charles the First,” whose Queen he now assisted in her escape through Cornwall to France. Essex evidently did not stay long in Launceston, for when the King joined Prince Maurice at Exeter and marched into Cornwall, ” some of his horse and foot entered into Landson (July 31), all Essex his army being gone thence and no resistance.” On that day Charles, who remained on the Devonshire side of the Tamar, received a message from Sir Richard Grenville desiring his majesty to hasten towards the West, and ” the King bid the fellow tell him he was coming with all possible speed with an army of 10000 foot, 5000 horse,and 28 piece of cannon.” The next day the King and the remainder of his forces crossed Poison Bridge, passed through Launceston, and ” marched to Trecarel in the psh of Lysant and lay there at the house of Mr. Manaton in com. Cornubia,” while ” the whole army lay this night round about this house in the field,” the men having been cheered on their way from Poison by the fact that “a fellow that was carrying letters from Essex was taken and hang’d below the rendezvous that all the army might see him as they marched by.” The King did not remain at Trecarrell more than one night, proceeding the next morning to Liskeard, whence he advanced towards Lostwithiel, and the greater part of the month was occupied with skirmishing, Essex refusing to treat because he had no authority from the Houses to do so. On August 31, the Parliamentarian horse began to retreat from Cornwall, and ” the King supposing they would go through Liskerd and Launceston sent 2 messengers of our troope, Mr. Brooke and Mr. Samuel West, with a letter to Sir Fr. Donington (who hath a 1000 horse in Devon) to stop their march. But the enemy went not near Liskerd this day, but went right to Saltash to ferry their horse over into Devonshire.” On the same day, the King gave battle to the Parliamentarian forces at Lostwithiel and completely defeated them, but Essex had fled with the horse, leaving Major-General Skippon to negotiate a surrender. Charles, a few days later, withdrew to Liskeard and thence from Cornwall, not again passing through Launceston, however, but proceeding direct from Liskeard to Tavistock. It was not much wonder, after such a severe reverse to the Parliamentarians, that Cromwell was moved to exclaim “We do with grief of heart resent the sad condition of our Army in the West, and of affairs there. That business has our hearts with it ; and truly had we wings, we would fly thither! So soon as ever my Lord (Manchester) and the Foot set me loose, there shall be in me no want to hasten what I can to that service.” But it was eighteen months before his aspiration could be realised, and for twelve of these, as far as Launceston was concerned, there was cessation of active strife.

But though there was no fighting in the neighbourhood for this period, political warfare raged keenly within the borough’s walls. The majority of the Corporation was Royalist, but one of the aldermen at least, Thomas Bolitho by name, was not afraid, even though the town was held by the King’s forces, to stand up in behalf of the Parliament, and he suffered for his temerity. According to a petition presented by him to the Lords on June 19, 1646, he went to Plymouth two years before “and took up for the service of the Parliament,” for which act he was indicted at the Town Court as a rebel, and was on February 3, 1645, deprived by the Corporation of his place as alderman of the borough. As long as the Royalists still triumphed he held his peace, but when they were overthrown he prayed the Lords that he might be restored to his aldermanship and might receive reparation for the wrongs inflicted upon him. And the Lords, impressed with the justice of his plea, immediately ordered “that the said Bilithoe shall be restored to be a Burgess of the said Town of Launceston, and enjoy his Privilege.” *At a borough court, held 7th September,

1646, before Thomas Hicks, mayor, and five aldermen, it is recorded that “Thomas Bolithoe is admitted to his former place of alderman of the borough, and Charles King is deposed from his place of alderman, to which he was lawfully elected.” Two days later Mr. Bolithoe was made mayor, and on the 19th day of the same month of September, he convened a special meeting at the Speech House. There he triumphantly led the humiliated aldermen to pass the following resolution :

*Uppon consideration had how that about the begynnyng of the late unnaturall warre, leavied and mayntayned by a malignant party in this K’ingdome agaynst the Parliament and their adherents, when as Sr Ralfe Hopton and his forces, in a hostile manner, were entered and contynued in this county, and some forces were alsoe raysed and brought into this towne by order and direction of the Parliament for the necessary defence and preservation thereof agaynst the said Sr Ralfe Hopton and his army, Ambrose Manaton, Esquire, then Recorder of this towne and justice of peace of this county, and alsoe a member of the house of Comons, with the assistance of some other Justices of Peace who joyned with him therein, by color and pretence of their authorite as Justices of the peace, caused and required the then Sheriffe of this County to rayse the power of our County; which being don accordingly, and joyned with the said forces of the said Sr Ralfe Hopton, by meanes thereof the said Sr Ralfe Hopton grewe soe potent that the said forces of the Parliament then remayning in this Towne were unable to make resistance and stand agaynst him, but were enforced to disband and leave this Towne : Whereuppon the said Sr Ralfe Hopton entred thereinto, and thereby, as well the said Towne and the inhabitants thereof, as this whole County were subdued and brought in subjection to the power and tyranny of the enemy (the King) by reason whereof (besides the manifold pressures and grievances under which they lay for a long tyme after, even untill the comyng in of his Excellency Sr Thomas Fayrefax and (his army), the whole kingdom hath byn putt into great hazards and danger : And likewise that the said Mr Manaton, being Recorder heere, was also chosen to be one of the burgesses of this Towne to serve in the present Parliament, and was thereupon admitted to be a member of the house of Comons accordingly, nevertheless, contrary to the trust reposed in him by this Borough, he hath deserted -the Parliament, and adhered to their enemyes and joyned himselfe with an unlawfull assembly of malignants at Oxford, and was one of them who did usurpe the name and power of a Parliament, and voted both kingdoms to be traytors, and hath soe misbehaved himselfe towards the kingdome and Parliament that the said house of Comons hath adjudged him unworthy to contynue any longer to be one of the members thereof, and by their vote and comon consent, have given order that a writt shal be issued for the elecion of an other burgesse for this Towne in his roome ; and for diverse other waightie matters and causes, the said maior and aldermen, with an unanimus consent, have agreed and resolved to put out and remove the said Mr Manaton from the said place and office of Recorder of this borough, and dyd instantly remove and putt him out of the same : And afterwards, at the same meeting, the said Maior and Aldermen, with one unanimus consent, did elect Thomas Gewen, Esquire, to be the Recorder of the sd borough; And the said Thomas Gewen afterwards the same day, before the sd Aldermen and the Towne Clarke of the said borough, tooke the severall oathes of supremacy and alleageance, and likewise the oath specially appointed to be taken for the due execucon of the said office of Recorder of the said borough.

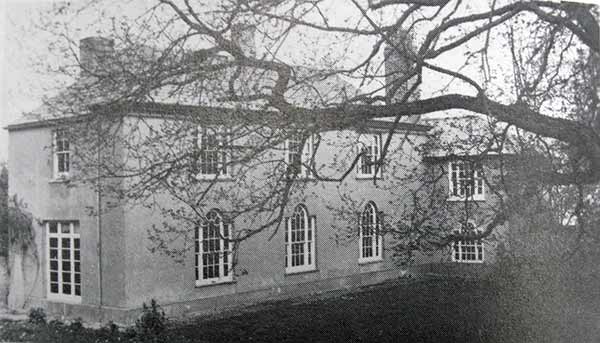

The autumn and winter of 1645 will be ever memorable in the annals of Launceston because of the sojourn of Charles Prince of of Wales in the town. “When the prince,” says Clarendon, “came to Launceston from Exeter (which was about the middle of September) after the loss of Bristol, and the motion of the enemy

inclined westward, it was then thought fit to draw all the trained bands of Cornwall to Launceston (under the command of Sir Richard Grenville;) . . . The day after the Prince came to Launceston, Sir Richard Greenvile writ a letter to him, wherein he (re) presented the impossibility of keeping that army together, or fighting with it in the condition it was then in.” Dissensions, in fact, filled the royal force ; Lord Goring, the commander of the King’s forces, who had been defeated by Sir Thomas Fairfax, thought himself badly served, and Sir Richard Grenville was at variance with several of the other officers as well as with the Cornish gentlemen, who through their commissioners (of whom Coryton was one) presented to the Prince “a sharp complaint against him in the name of the whole county, for several exorbitences and strange acts of tyranny exercised upon them.” It was immediately after Goring’s rout that the Prince visited Launceston, from which town his royal highness addressed a letter to the defeated general on July 26, regarding the heavy pressure of the military upon Cornwall and Devon. As soon as the Prince entered Cornwall, his mission was so referred to by the Parliamentarians as to show how little they feared he would succeed. “Observe,” said one of the Puritan newspapers “how they hurry poor Prince Charles from place to place, by his presence to raise the better supplies, and now at last to his Tenants in Cornwall: they will make him spend and adventure all his Interest before they have done with him.” The earliest effort the Prince made in the county was evidently at Launceston, where first he stayed, and where without doubt it was that “hee lately made a speech to the Countrey-men, wishing them, That as they had

formerly, so they would still continue to stand for their Prince, and that they would raise all the strength they could to oppose the Rebels.” But the old difficulty arose once more, for “the Cornish promised, That they would assist him with their lives and fortunes in their owne Countrey, but would not be perswaded to stir out of it.” “The truth is,” sadly observed a Royalist newspaper a fortnight later, “the Cornish men are unwilling to come out of their County, and many of them begin to imbrace an indifferent good opinion of Sir Thomas Fairfax Army.” Just at the same time as this was published, “Prince Charles with Hopton, Greenvile and the rest kept his Rendezvouz at Launceston in Cornewall; they cannot raise in all above 5000 horse and foot at most . . . The Prince cannot raise above 1500 to bring out of Cornewall the Trained-bands absolutely refusing to stir.” Goring then resolved that the whole of his army (including his foot quartered at Okehampton, his horse at Lidford, and Sir Richard Grenville’s men at Tavistock) should rendezvous at Launceston, preparatory to a march into Devonshire. The result was a disappointment, and the Prince, writing from Launceston on September 1, dwelt upon the small attendance of the trained bands at the day appointed, and adjourned the muster until the 24th of the same month.

The Prince continued to make Launceston his head-quarters, and on October 14 sent a letter hence to Col. P(iers) Edgcumbe ordering him to bring up more troops. But his mission had failed, and although one Parliamentarian newspaper could in this same month positively assert that ” The Prince was Munday the 20 instant at

Launston,” other journals gave most conflicting accounts of his movements, one even inserting a rumour (while the Prince was still in all probability located in Madford House, the finest dwelling then in Launceston although Richard and Otho Peter believe he possibly lodged at the assize hall, within the Keep Court of

the Castle.) that he had fled to France. Through most of the winter his royal highness remained in the town, endeavouring to heal the differences between Goring and Grenville, but his efforts were in vain, and the latter proved so insubordinate that the Prince had no alternative in the beginning of 1646 but to cast him into prison in Launceston Castle. The cause thus divided against itself did not long stand. “The imprisonment of Greenvill hath caused some distractions & mutinies amongst them,” we are told in the February, “the Greenvillians who are most mutiners being much displeased at it, and unwilling to be commanded either by the Gorians or Hoptonians.” Launceston was in fact the scene of many Royalist distractions. “From the Enemies Quarters,” says a Parliamentarian journal, “we have advertisement by some prisoners who came about Exchange from Lanceston, That many of the Cornish Souldiers which were taken at Dartmouth, upon their comming into Cornwal, much boasted of the clemencie of his Excellencie Sir Thomas Fairfax, who had not only spared their lives when he had them at mercy, but also gave them their liberties, and two shillings apeece. These comming to Lanceston, were questioned by Hopton’s forces whether they would serve the Prince or no, which they refusing, about thirty of them were clapt up prisoners.” The Prince left Launceston on Friday, 29th August, and went thence to Exeter. A

Despite these differences, the neighbourhood of Launceston continued to be well guarded against a surprise, as Major Seely, of the Parliamentarians, found when he ” was opposed by the Cornish, as he would have gone over Ponstor (Polson) Bridge, whereupon he retreated back to Leyton (Lifton), where he quarters“; but the

Prince discovered, soon after he had imprisoned Grenville, that his position was fast becoming untenable. He had not only to contend with quarrels among his generals but with mutinies among his troops, and now desertions were frequent. In the last days of January he accordingly “retreated further into Cornwall, and his Forces quitting Launceston, carrying what Provisions they could out of that Port of Devon (sic) into Cornwall.” Of this movement, Sir Thomas Fairfax gave a striking account in a letter to Speaker Lenthal, written at Chudleigh on February 2.

“Tuesday last,” he says, “divers ploughs and horses, all laden, some with provisions, have been sent out of Launceston Westward ; there was also great store of Bread baked, the Bread was brought in flaskets from a Bakehouse in that town, where it was baked by the Princes Baker, and was immediately sent away Westward; six or seven ploughs more were drawn out of Launceston on Wednesday night Westwards, also further into Cornwall, much of their Lading was Musquets, Pikes, and other Ammunition ; the rest of the Lading was Victuals, as poudred Beef and Cheese, with them were about fifty horse, laden with Powder, Match, and Bullets, and Lead which they had taken off from the Castle, so that, it is all unleaded ; much of the Ammunition was loaded out of Guild-hall, which is their main Guard ; on Thursday night neer fifty more horse laden with provisions, as Bacon, Pork, and such like, were sent the same way, all reported to be for the Princes Court . . . Thursday also the prisoners in Launceston were turned over from Greenvile’s Marshal to the Lord Hopton’s Marshal; fifty Souldiers ran the same day out of one Regiment; those that they gather out of the country run away daily : Friday, six ploughs more were drawn into the castle green to be loaded, with them were forty horse, with pack-Saddles, Crooks and Paniards ; these were all reported to be sent after the rest : That day thirty Hogsheads of Syder were brought into Launceston from Merrington (Werrington), which were likewise to be sent Westward for the Prince ; and the Marshal gave order this day, that the prisoners in Launceston should be carried to Truro . . . The Trained-Bands of the town of Launceston get others for money to serve in their rooms ; the Trained-Bands further West will not rise at all. There is now but one Iron Gun in Launceston, which is an Iron piece planted between the Princes Quarters and Guild hal ; the poor people pull down the Works about the town to get away the Wood, none hindring them; the Prince and Hopton were Saturday, Jan. 31, both in Launceston.”

The Prince had returned to the town a day before the date mentioned, only to hear that on the Thursday (Jan. 29) there had been “a mutiny in Launceston between some of Hopton’s men and some of Greenvills, which made many of the common Souldiers crie home, and accordingly some ran towards Greston (Greystone), some towards Braston (Bradstone), and some to other places.” His royal highness (who was accompanied by Hopton, the Earl of Berkshire, and Sir Edward Hyde, afterwards the Earl of Clarendon) “took much pains “on the Saturday, then the Launceston marketday, “to appease the souldiers and the Countrey-people.” The Prince remained with Hopton in the town for some days, and during his stay the Royalists are reported to “have defaced much the Castle of Launceston, by taking away the Lead, and giving the Timber to the people to burn, who pull down the Works. “His royal highness then proceeded to Holsworthy, the head-quarters of Goring’s horse (a portion of which lay at North Petherwin), and next by way of Truro to Pendennis and thence to France. Before departing, the Prince commanded the trained-bands ‘ ‘ to keep guards on the river day and night,” and a party of Royalist horse was posted at Lifton to cover the way to Polson Bridge and thence through Launceston into Cornwall.

Dartmouth had been taken by storm in the middle of January, and on February 16 Fairfax advanced on Torrington, where he defeated Hopton. The latter, who was wounded in the fight, fled on the night of the battle to Launceston, and, leaving Colonel Bassett to defend the town, went into the West. Fairfax remained at

Torrington for a week and then, having despatched a force to occupy Stratton, advanced into Cornwall by way of Holsworthy, the townsmen of which “shewed much cheerfulnesse” at sight of the Parliamentarians. On the morning of Wednesday, February 25, the Army marched from Holsworthy towards Launceston, “which place was reported to be strong, and to have 1000 in it of mercenaries and Train-men.” On the way some fifty prisoners were captured, and “when we came within two miles of Launceston our forces took divers of the Enemies Scouts, and some straggling Parties, who were most of them drunk; those who were best able to expresse themselves boasted, That Col. Basset was resolved to maintaine the Towne against our Forces ; whereupon our forlorn hopes of Horse and Foot were sent to enforce entrance, the Enemy having shut the (North) Gate, and the Towne very strong, made some opposition, but Sir Thomas Bisset Generall of the Horse, and Col. Blits Governour of the Towne, with Col. Strevaticans Regiment of Foot, in all about 500 Horse and Foot, having quitted the Towne about an houre before we came, and left it onely to some few of the Trained Bands, they after some resistance retreated; our men entred, tooke some Prisoners, and

killed onely two, it being now dark the rest escaped : we seized upon the Armes and Magazine in the Towne, the inhabitants seemed generally to be much revived at our comming, being sensible that they were formerly but deluded with the blandishments of the Kings Party, pretending what they did was in defence of the King, when indeed it was chiefly to the destruction of the Subject. Our Souldiers notwithstanding the opposition they received at the entrance, did not then nor 6ince plunder any one house that I know of, but demeaned themselves very civilly.” This is Curtis’s narrative of the capture of Launceston, and Rushworth’s letter does not add many details, while it corroborates the statements that the Launcestonians were glad at the coming of the Parliamentarian forces and that these latter behaved well after they had taken the town. The only point to be noted in another contemporary account of the fight is that after the Cavaliers had been put to flight in great disorder “by the darknesse of the night, narrownesse and steepnesse of the wayes, most of them escaped.”

“The Horse and Foot,” wrote Rushworth in a postcript on the morning after the battle, “have been put to hard duty upon the march, and Guards, and going out upon parties, so that I beleeve we shall not heare (? leave) this day.” The prediction proved correct, for until the Saturday “the head Quarter continued at Launceston, the Foot being much wearied out with the two dayes martch before.”

*Mr. Sprigge, who was a chaplain in the army of Fairfax, and personally witnessed the occurrences which he describes, states that it was twelve o’clock at night on the 25th February before the rear of the army arrived at Launceston. He adds :

Within two miles of the Towne, three scouts were taken, who informed of Colonel Basset being in the towne, with five hundred foot of Colonel Tremayne’s, and some horse. A forlorn hope was sent before to demand the towne. The gates were shut upon them. The enemy (Royalists) resisted. Two of them were slaine, about an hundred taken. At last the enemy was put to flight in great disorder. By the darknesse of the night, narrownesse and steepnesse of the wayes, most of them escaped ; and our men possessed the towne which had been garrisoned by them. Thursday, 26th. The headquarters continued at Launceston, the foot being much wearied out with the two dayes martch before. The General (Fairfax) viewed the ancient Castle of Launceston, scituated upon a mount, raised very high, but not

fortified. The works and mounts on the top of the hill the enemy left standing undemolished. Many Cornish were taken prisoners in the towne the night before, who, being brought before the General this day, had twelve pence a peece given them, and passes to goe to their homes. The towne’s people in Launceston were much affected with such mercifull usage. The army in their martch into Cornwall, thus far, had much cause to observe the people’s frights, quitting their habitations in feare of the army; the enemy having insinuated such an ill opinion of it into them, endeavouring to make them believe, by oaths and imprecations, that no Cornish was to have quarter at our hands j of which prejudice and misprission, after the people were undeceived, they frequented the markets again as in former time. This day (26th) a letter was sent to Plymouth for the Cornish gentlemen there to hasten to the General to Launceston. The rear guard of our horse were appointed to quarter along the river Tamar, the better to prevent the breaking through of the enemie’s horse, an evill which his Excellency had ever a watchfull eye upon to prevent. . . .

Friday, the 27/h. The headquarters continuing still at Launceston, the Plymouth regiments of foot were sent unto to come from Tavistock thither, and the residue to lye on the passes upon the river, the more effectually to interrupt the enemy, if he attempted to break through.

*The borough accounts disclose that on this day the town presented to the Parliamentary General (the recording angel discourteously calls him ” Sr Thomas Feare Fox “) “2 suger loafts,” at a cost of 15 s. 2d. Poor Richard Carou, whom we lately found serving the town arms, required a shroud on this same 27th February. He may have been one of the two who ” were slaine ” in the attack at midnight of the 25th.

*Sprigge continues :