.

1914 and all that (With thanks to Jim Edwards)

European Boundaries December 1914

At the beginning of 1914 Launceston, like so many other towns in the country had a lot to look forward to. Contact with the outside world was so much easier with the coming of the railway and goods could come and go at a more rapid speed. More importantly, the railway terminus had provided the town with an upshift in its fortunes, after nearly 70 years of stagnation when the assizes were closed and moved to Bodmin in 1835. A new water supply had been built at the Windmill and electric lighting was available from the Launceston Electricity Generating Station at Newport. A new County school had only just opened the previous summer at Windmill Hill, built at a cost of £3000 and with room for 300 pupils. Yet even as the opening of the school was being reported in the Western Times newspaper of 2nd August 1913, there appeared on the same page, an article detailing the fragile relationship between the peoples living in the Balkans. A year and 2 days later that fragility unleashed a storm that encompassed the whole World and affected the lives of so many people forever. Distant or unheard of places such as Kut, Dorian, Loos, Ypres, Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele would all become synonymous with the town as the men and women of Launceston and its district did their bit for King and Country. Many paid the ultimate price for victory and many others had their lives permanently changed forever.

At home much was done to help the national cause as the letters to the Cornish and Devon Post show:

Post & News, 15 August, 1914. Borough of Launceston. Patriotic Needlework.

Launceston District Working Party.

Sir, It may be remembered that the following letter was inserted in your paper last year:- “It is suggested by Mrs J C Williams, that a working party should be organised in this district to work should war occur.

The arrangements of the meetings which are being formed in various places exist only on paper at present, and it is hoped may long remain so. The object is that when occasion arises the members

may be called together at once to work from instructions from headquarters on suitable and useful articles for our soldiers and sailors. Mrs Williams will act as president and it is at her request that I ask any who are willing to join to kindly send their names and addresses to me. The vice-presidents are asked, on being called to work, to give 5s., and members 2s 6d., towards expenses and materials.”

In response nearly 40 sent in their names. Unfortunately the time has now come to organise these meetings, and as soon as instructions and patterns can be obtained from headquarters and arrangements made, these who have joined will receive a notice. In the meantime, there may be others who, now that the necessity has arisen, may care to join. Will any such send in their names and subscriptions to me before Wednesday 12th instant?

Yours faithfully, LB Peter, Hon.Sec.

Finance Committee (V.A.D. Cornwall 18), Craigmore, Launceston.

Post & News, 29th August, 1914. Garments For The Wounded.

Letter to the Editor:

Sir, May we suggest that many people have stores of worn sleeping suits, men’s shirts, and other garments suitable, after repairs, for the use of those convalescents leaving the hospitals. We feel sure that many articles of this description have been put aside by their owners for emergencies, and in sent to the undersigned would be gratefully received and put in thorough order for the use of the wounded and others in distress in consequence of the war.

All parcels kindly address to: Mrs Turner, Pen Inney, Lewannick: Julia E. D. Rodd, Trebartha Hall: Susie S Kittow, Tredaule House: Mrs Wramgham, Bowden Derra.

Florence Turner, Pen Inney, Lewannick, Launceston, Cornwall. August 26th.

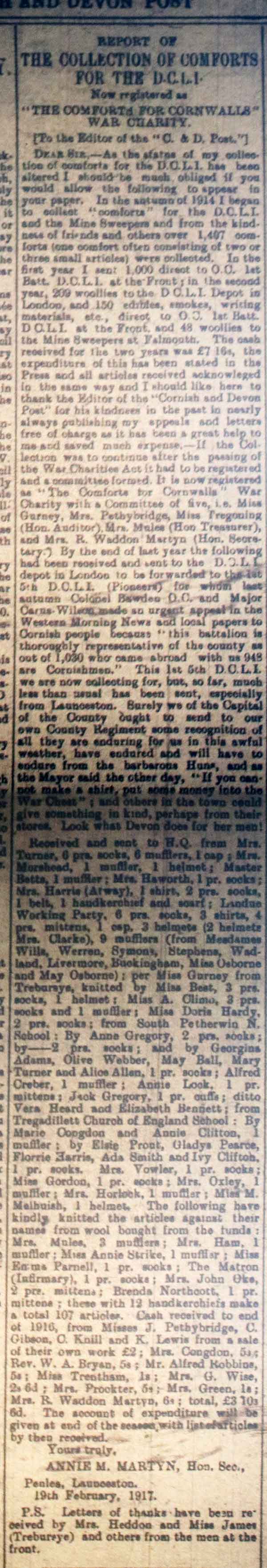

Post & News, 6th January 1917:

Royal Appreciation of War Hospital Supply Work In The Launceston District.:-

To The Editor of “C & D Post:” –

Dear Sir, I beg to enclose a copy of a letter just received showing the interest H.R.H. Princess Christian is taking in our branch of War Hospital Supply Work. I should be greatly obliged if you would be so good as to publish the letter in your next issue, also the acknowledgement. Yours Faithfully, A.S. Cope, Trelaske. January 2nd.

Schombury House, Pall Mall, S.W., Dec. 31.

Sir, I am desired by her Royal Highness Princess Christian, to write to you and ask you to convey to all those who belong to the Carpentry Branch of the Belgravia W.H.S.D, Launceston Branch, the Princess’s great appreciation of the excellent work they have executed and so untiringly carried on for the benefit of our own wounded and those of our Allies.

The work is of the utmost value, and the Princess is anxious that all should know how much the appreciation all that is being done by this energetic branch in the noble cause of ministering to the needs of the sick and wounded..

Believe me, Yours truly, (signed) Enid du Cane, Lady-in-Waiting.

Launceston Branch of the Belgravia War Hospital Supplies Depot,

Carpentry Depot, Trelaske, near Launceston. Jan 2nd. 1917.

Madam, On behalf of the Launceston Branch of the Belgravia Work Rooms, W.H.S.D., I have the honour to acknowledge your Ladyship’s letter of the 31st, ulto. conveying to the workers here Her Royal Highness Princess Christian’s gracious message.

Will you kindly express to Her Royal Highness our warm thanks for her encouraging words and our high appreciation of the interest she takes in the progress of the work to the success of which she herself so greatly contributes.

Your most obedient servant, A.E. Cope, Hon. Sec. To the Lady-in-Waiting.

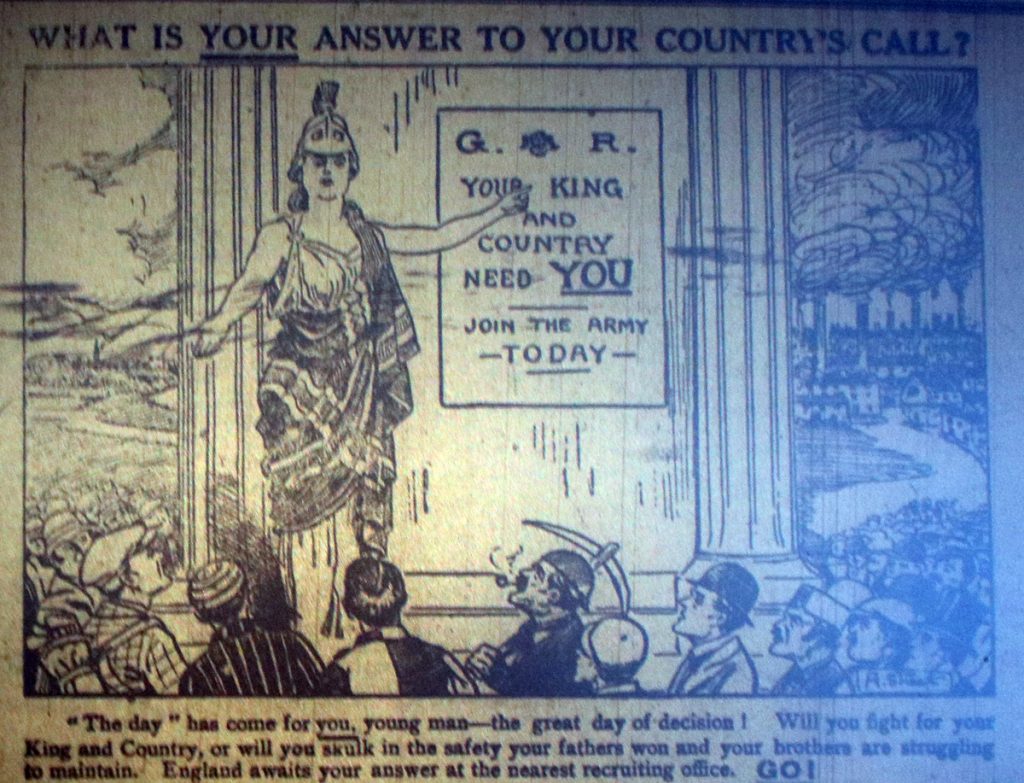

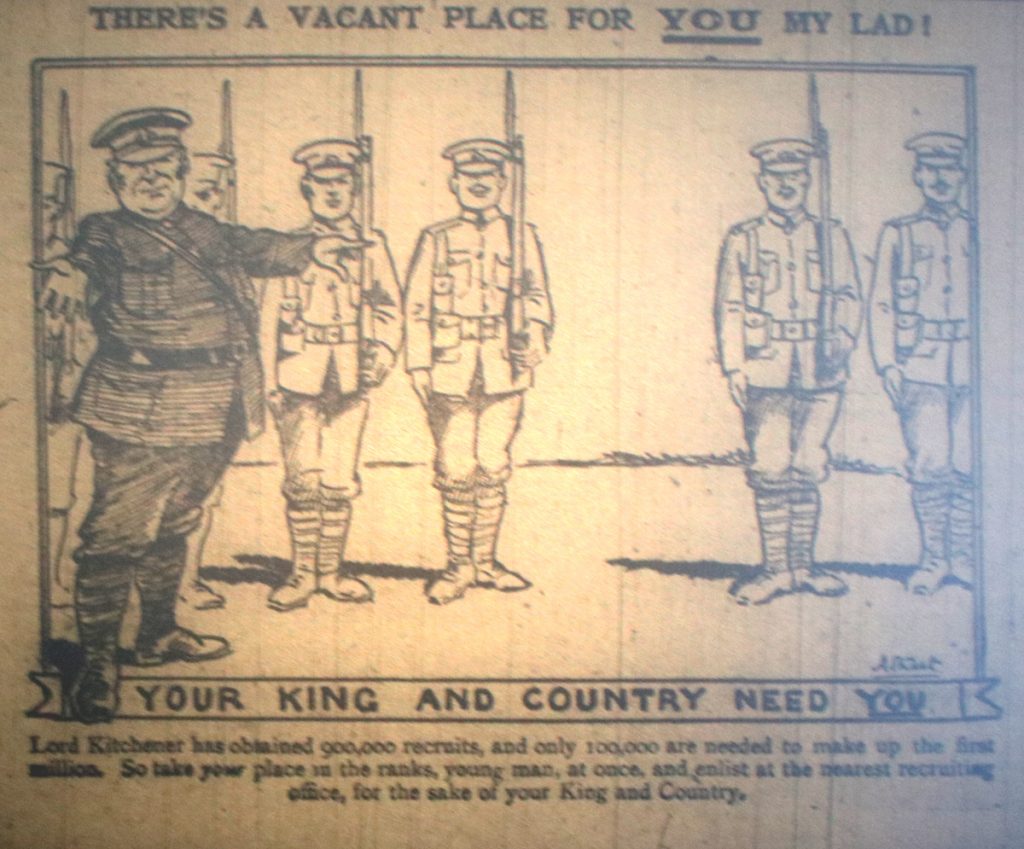

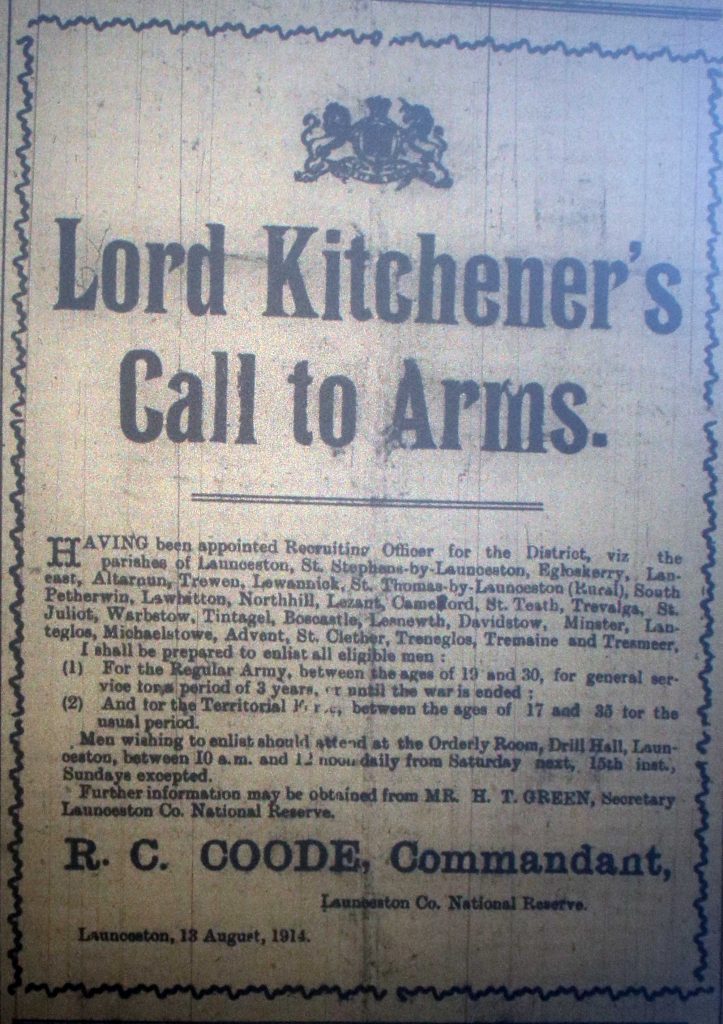

A Call to Arms and Recruitment.

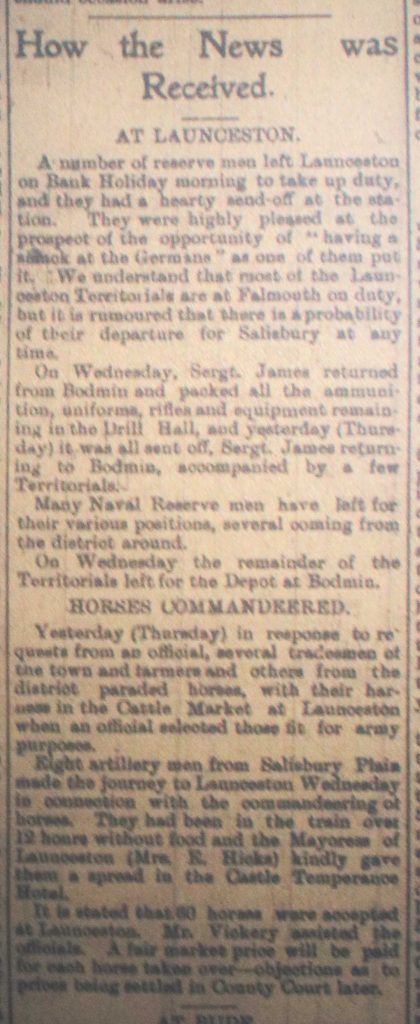

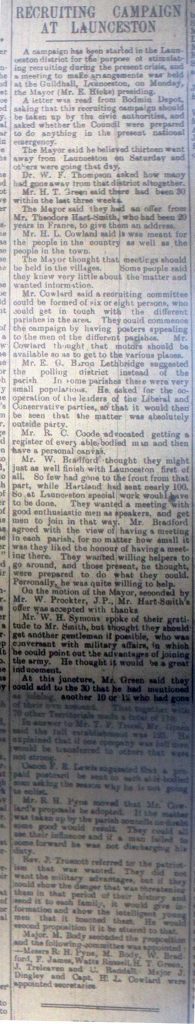

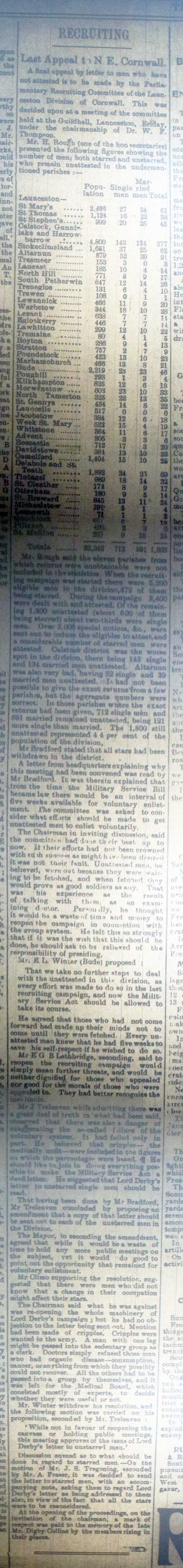

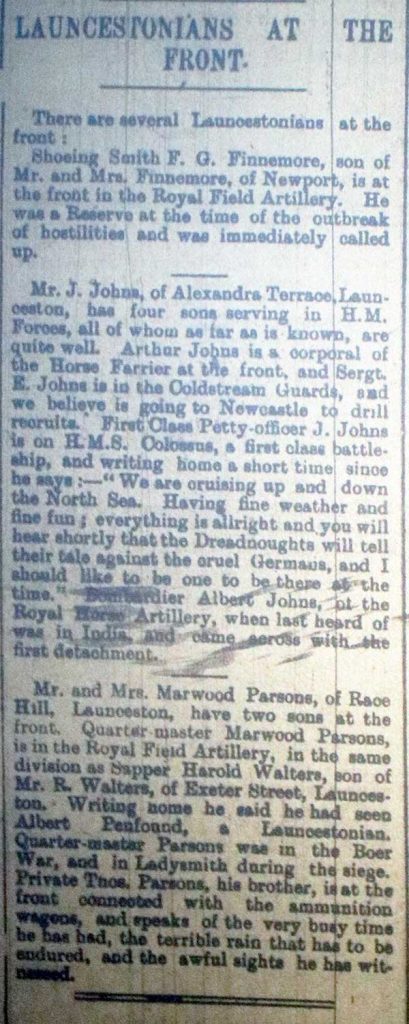

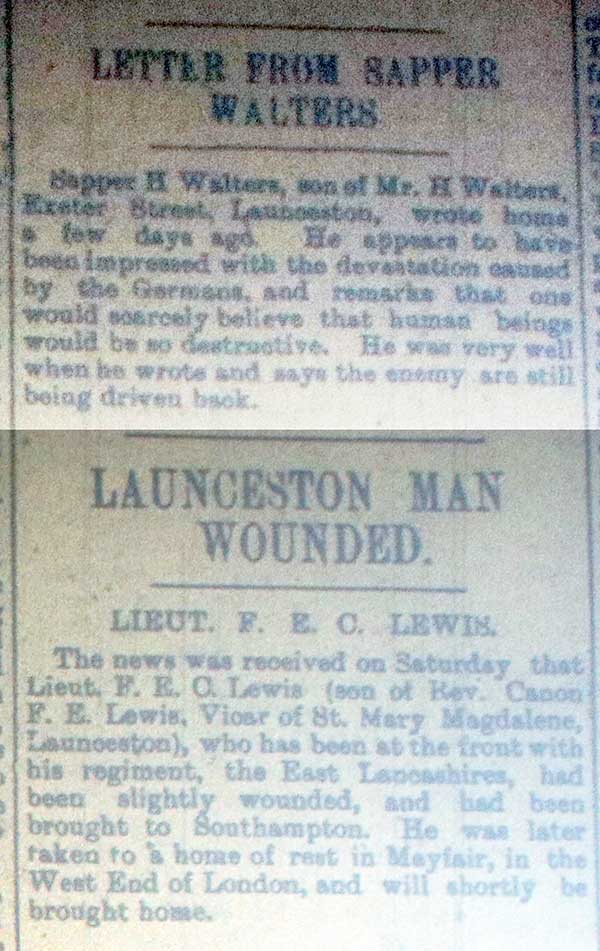

Launceston immediately sprung into war action with many men volunteering for service at the War’s beginning, with many already serving or others such as James Avery, the caretaker of the Launceston Sewage works at St. Leonards, who was a reservist with the R.F.A.. A number of these reservists left Launceston on the Bank Holiday Monday, August 1st, receiving what was described at the time as a hearty send off from Launceston Station. The Territorials, who happened to be in camp at the time at Woodbury Common, near Exmouth, were not allowed to return, with many of them being drafted to their depots – Bodmin and elsewhere. Those who, for various reasons, were not attending camp, received instructions on Tuesday August 4th, to report themselves to their depots by the following day. On Thursday August 6th, several tradesmen and farmers and others from the district paraded horses, with their harness in the Cattle Market, before an official who selected 60 that he deemed fit for military purposes. Eight artillery men were sent from Salisbury Plain to Launceston to take the selected horse’s back. Having spent over twelve hours in the train without food, the Mayoress, Mrs Edward Hicks gave them a spread that had been set up in the Castle Temperance Hotel in High Street. By the February of 1916 439 men from the Cornish side of the Launceston district were in service (not including Broadwood, Lifton, North Petherwin and Werrington which were in Devon). Altarnun being the remarkable stand out in the recruitment figures released on the February 5th, with a population of 879 the parish was providing a total of 91 men to the services.

One of the biggest concerns for many in the area in those early days of the summer was the exodus of much needed men and horses just as the harvests were taking place. Farmer’s representatives in Parliament impressed upon the Army authorities the necessity of avoiding measures which would interfere with the gathering of the crops. It was suggested that horses being used in harvesting cereal crops should be exempt from impressment for Army requirements. Lloyd George allayed fears when he agreed, stating that the “Government would work to facilitate the ordinary business of the nation to the utmost degree.” As it happened, owing to the good weather, the harvest of 1914 was performed earlier than usual.

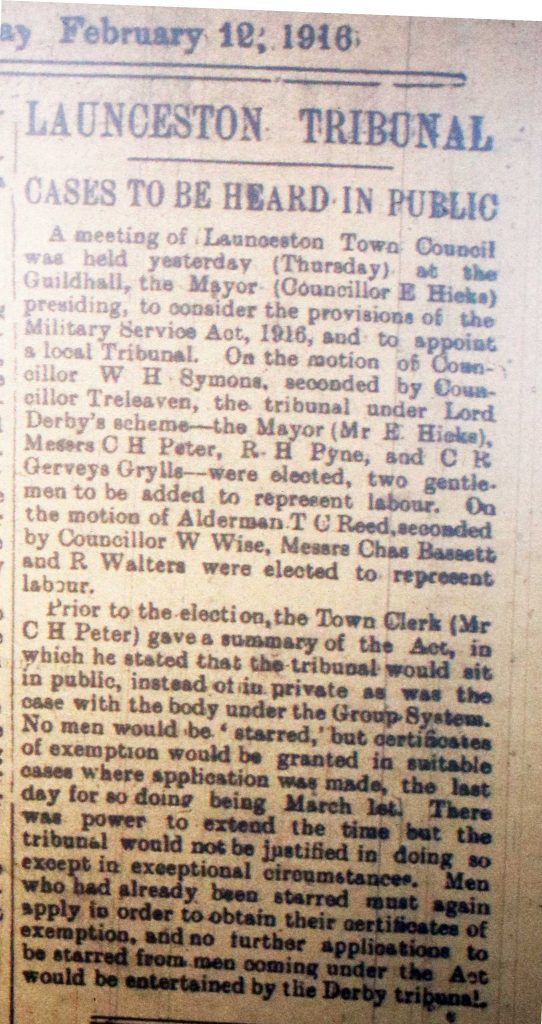

Launceston Tribunals

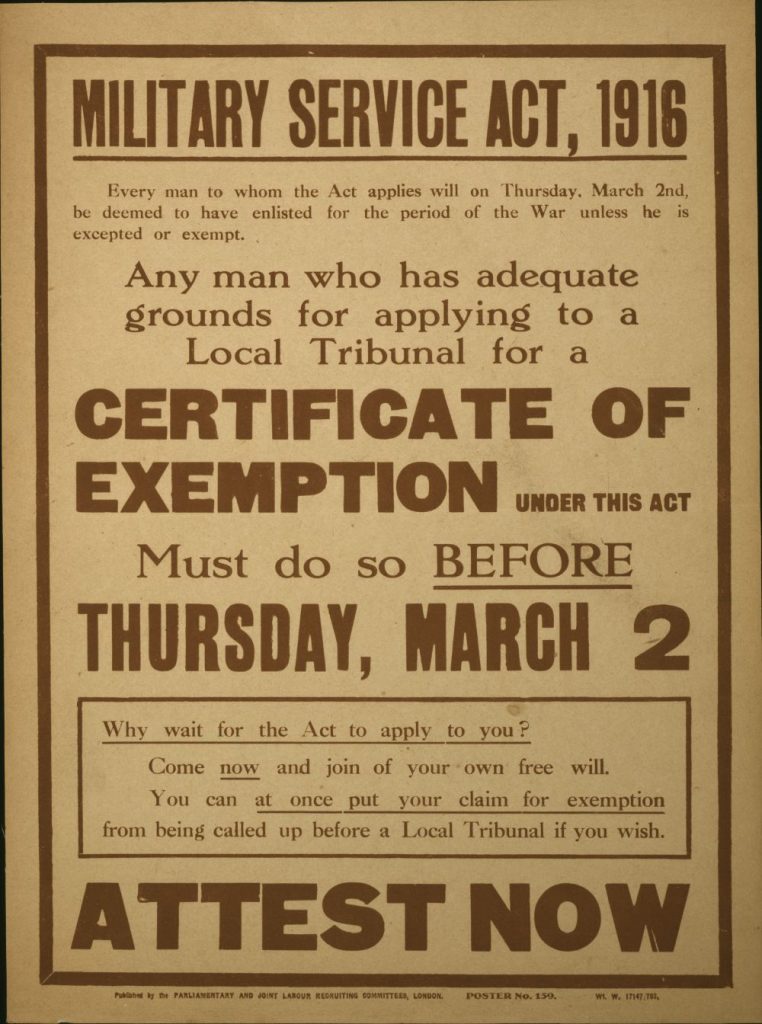

In January 1916 the Military Service Act was passed. This imposed conscription for the first time whereas previously the British Government had relied on voluntary enlistment, and latterly a kind of moral conscription called the Derby Scheme. It came into force on March 2nd, 1916. Initially, the Act specified that single men aged 18 to 41 who were outside of a protected occupation (those jobs considered of national importance) were now part of the army reserve and liable for immediate call-up. Also included were widowers without children. In May 1916 the Act was amended to include married men. By 1918 it had been extended in age range to 51. Men or employers who objected to an individual’s call-up could apply to a local Military Service Tribunal. These bodies could grant exemption from service, usually conditional or temporary. There was right of appeal to a County Appeal Tribunal. Local Tribunals were set up with Launceston Town Council holding a meeting on Thursday, February 11th, 1916 to set in motion the election to the Launceston Tribunal. The Mayor, Mr E. Hicks, Messrs C. H. Peter, R. H. Pyne, and C. R. Gerveys Grylls were elected, and to represent labour Messrs Chas Bassett and R. Walters were elected. Launceston Rural District Council elected Mr G. Lobb, and Messrs. A. West, A. Henwood, and W. Metherell. More

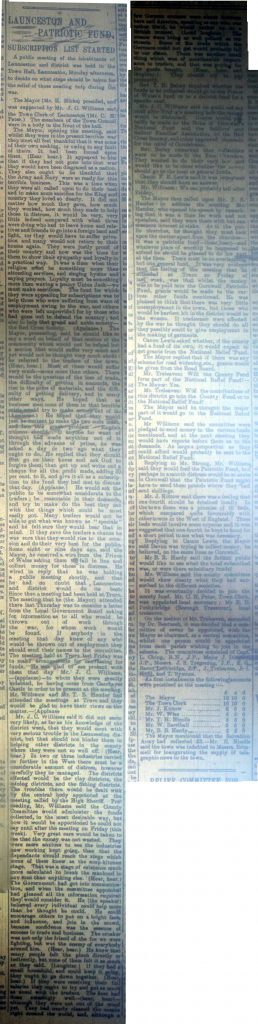

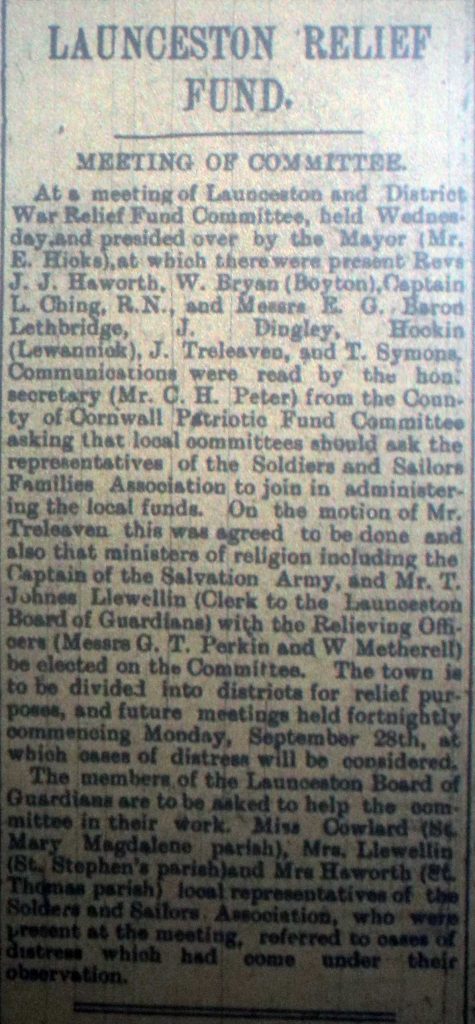

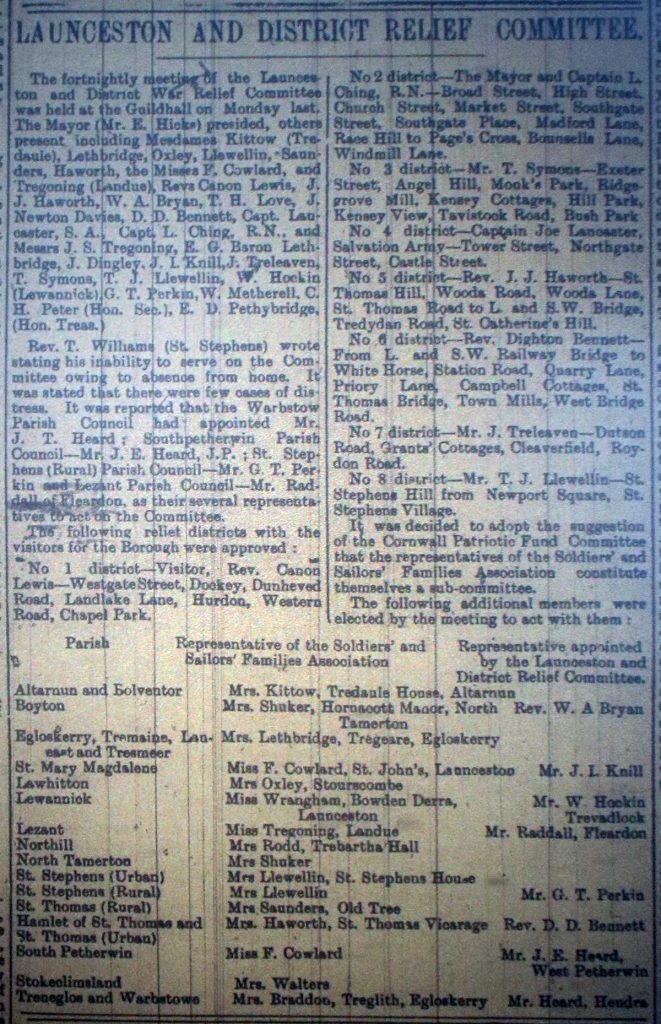

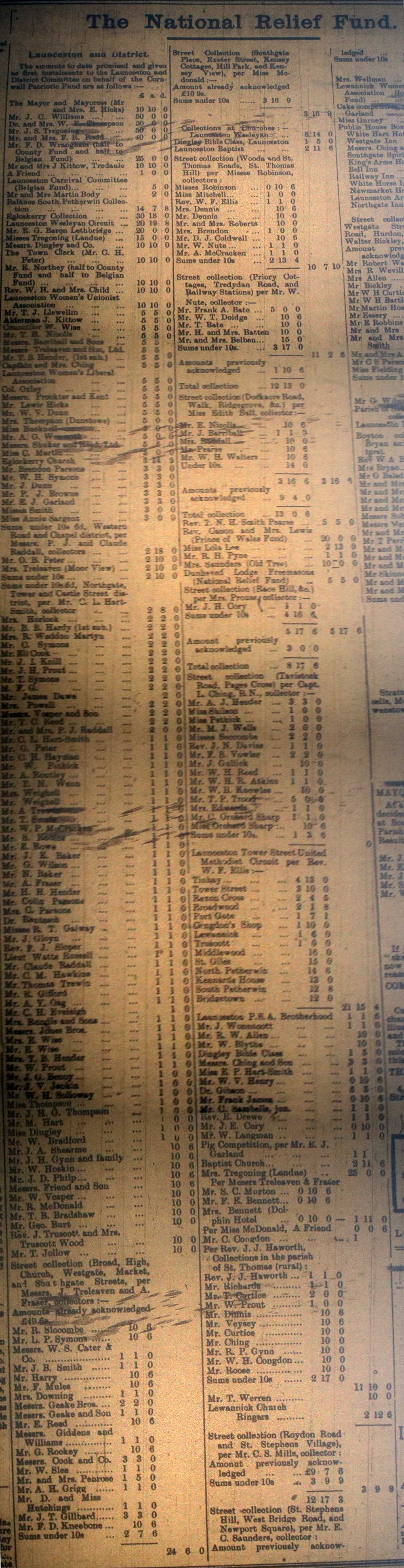

Launceston and District Relief Fund.

A National Relief Fund was set up with Edward, Prince of Wales, as treasurer, to help the families of serving men and those suffering from “industrial distress.” “At such a moment we all stand by one another, and it is to the heart of the British people that I confidently make this earnest appeal” the Prince said at the Funds inception. Within a week, donations to the fund had reached £1m. Launceston soon joined the appeal with the Launceston and District Relief Committee being formed at a meeting (below) held at the Town Hall on August 31st, 1914.

The German Invasion of 1914

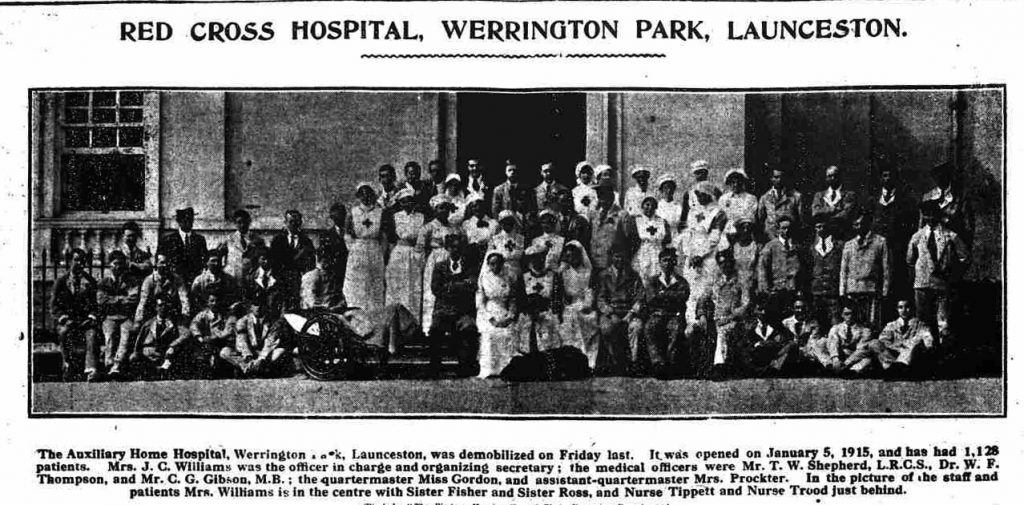

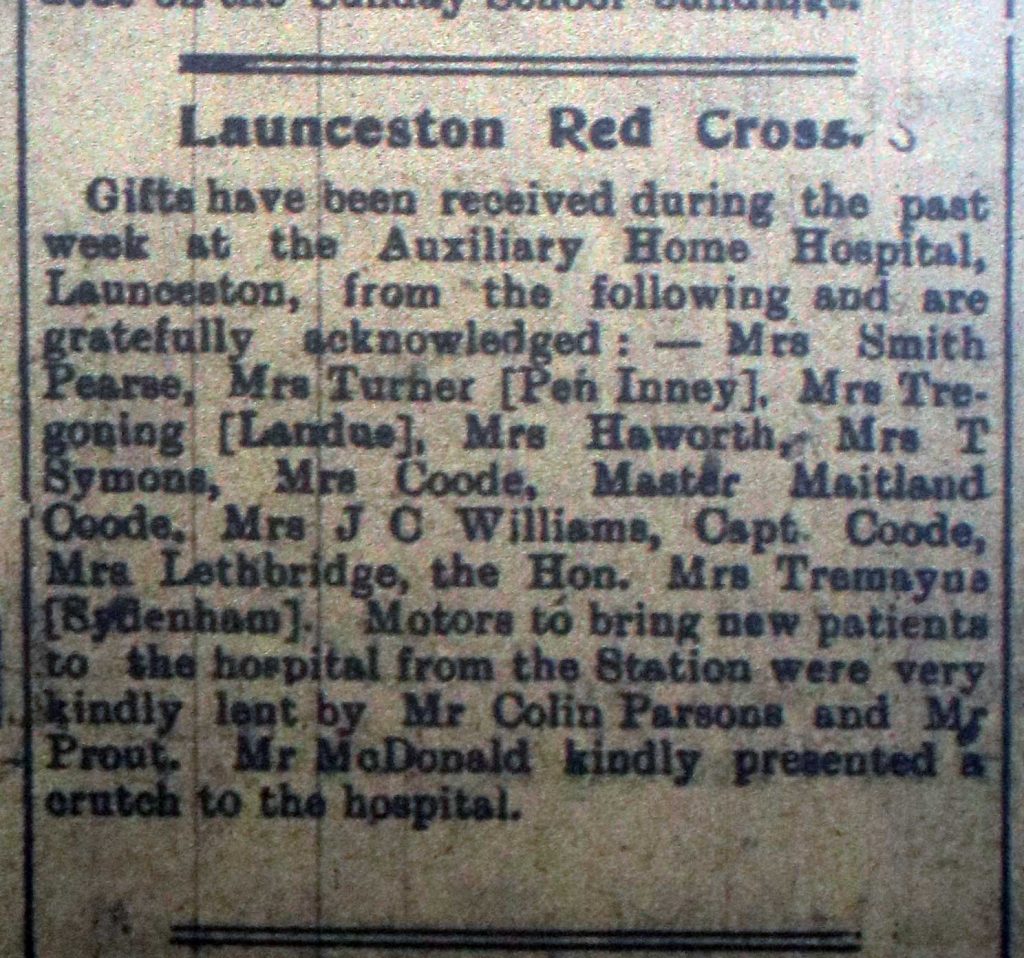

Voluntary Auxiliary Detachment Hospital.

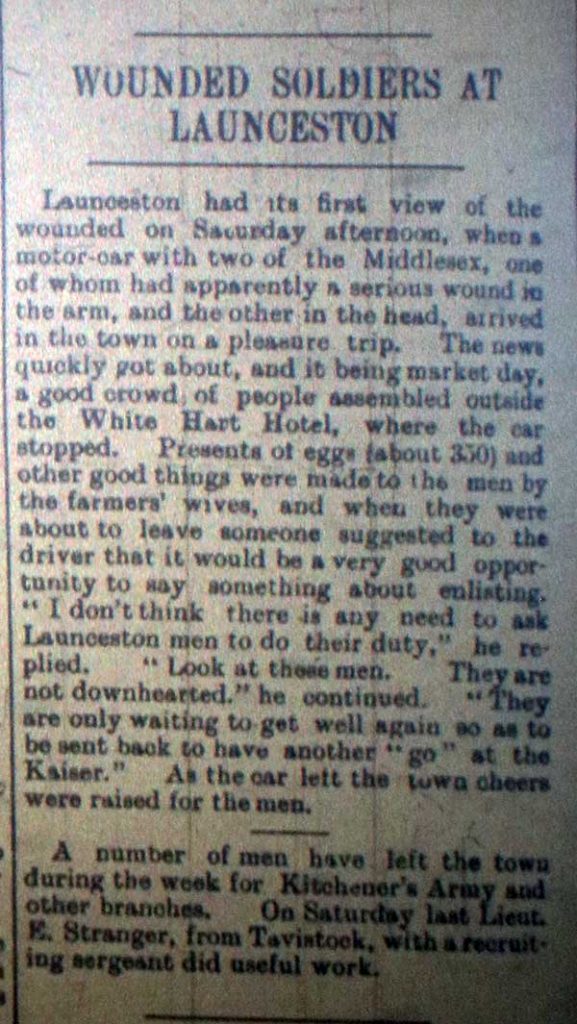

Just as important was the towns infrastructure, with the town hall (above) being used as a Voluntary Auxiliary Detachment Hospital for the wounded for the first few months of the war before it’s removal to Werrington House under the command of Mrs. J. C. Williams on January 5th, 1915, which then served as a convalescence hospital until it’s closure in March 1919.

For a full list of those that served the V.A.D. at Launceston go to the excellent British Red Cross website @ vad.redcross.org.uk

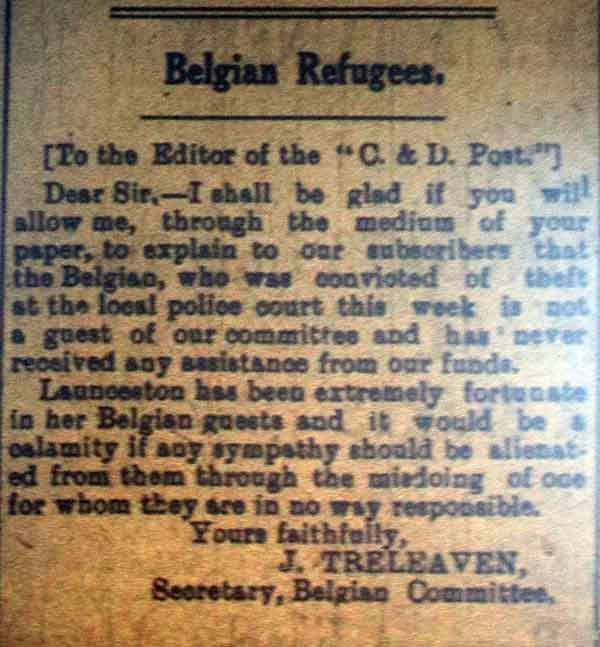

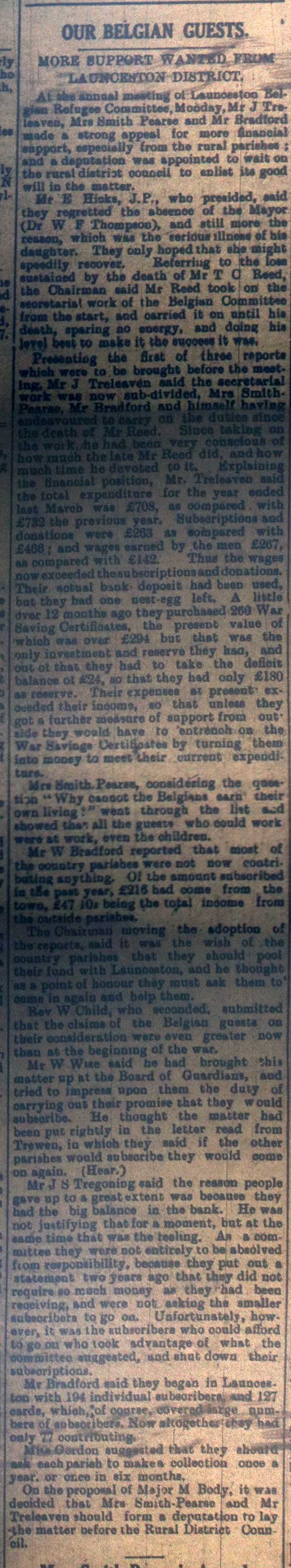

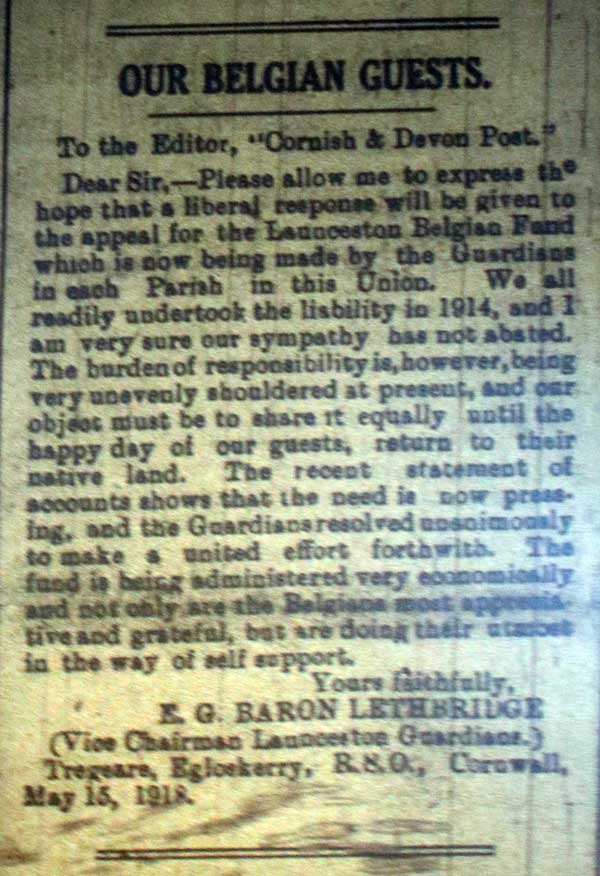

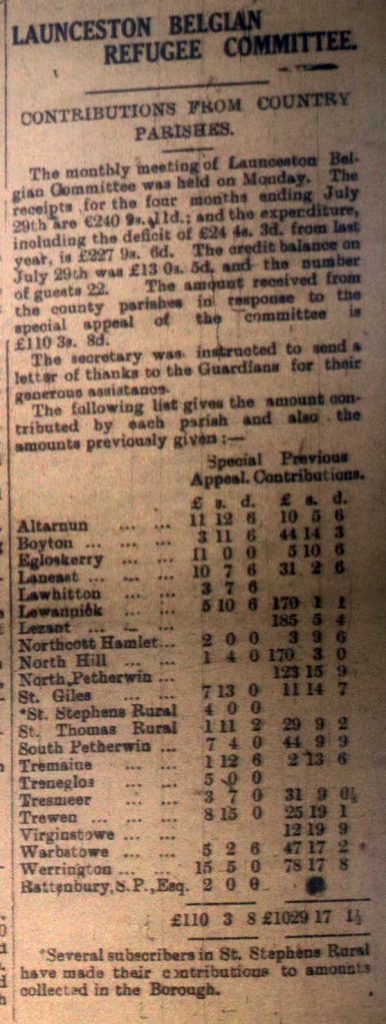

Belgium Refugees.

The terrible plight of ordinary Belgians facing the might of the German army, caused many to take flight from their homes. Writing home from his hospital bed after being wounded in December 1914, Shoeing-Smith Alfred Vosper said of the Belgians nightmare;

“The plight of the Belgian refugees was simply terrible, remarks Mr Vosper. Scores were to be met with every day, tramping from the battle area. On one occasion an old woman of about eighty was seen, being pushed along in a small cart by her son, who was himself grey-headed, whilst all their parcels and clothes were packed o the top of the old lady. The roads, which were like ploughed fields, were full of men, women and children with cycles, to which were attached their sole worldly belongings, tied in small parcels, their owners not knowing where to go. Babies were seen seated in small boxes on wheels used as a substitute for perambulators. In the 35th standing camp, many refugees passed their time, coming down at intervals when the kind-hearted soldiers saw that they did not want of food, going without themselves rather than the unfortunate people should be short.“

The town itself took up the mantle of helping by offering a safe haven for about 60 refugees in October of 1914. Initially, twenty two were chosen at Exeter by the Mayoress and Sister John Berchmons of St Joseph’s Convent, and Mrs T C Reed, who were brought by train to Launceston. Seven of the party that arrived were put up at St Joseph’s Convent, namely: Madame Donnay, Madame Tengels, both from Antwerp, Mademoiselle Wauthor, Ostend, and a family named Pitois, consisting of a mother and four children – Philomel (16), Julia (14), Joseph (10), and Melanue (8). The father, a carpenter, died six years ago. This family witnessed some of the terrors of the attack on Malines. Mde Donnay left Antwerp at midnight, when the bombardment opened and walked for sixteen hours. She was going to take a train, but before she could do so, the train was struck by a shell, four being killed and several wounded. Among the other refugees were an Antwerp policeman named Meuleman, and his wife and two daughters – Julia (16), and Bertha (11), who stayed with Mr and Mrs Cartwrights, the Ferns, St Stephens Hill. A relief fund was set up to help the refugees with many parishes organising events to help raise funds. The accommodation initially offered were two cottages at Altarnun, a farm house at Boyton, a house at Lifton, offered by Major Dingley, two houses at Polzeath , offered by James Treleaven and Mr. Symons; and a residence in Tavistock Road called ‘Hillside.’ There was some great debate as to some being housed in a part of the Workhouse where several large rooms were available which could have accommodated about twenty, or three or four families. However, it was felt that the cost of this should not fall on the boroughs rate payers. The Mayor stated that he was against the idea as would the Town Council also be. He was quite aware that the refugees might just need to be housed for six months, or possibly as long as two years! At Stoke Climsland not only did they manage to raise a weekly sum of £2, but they also put up a family in the parish as well. In the first three months of the appeal Stoke Climsland managed to raise £51 12s as well as sending two cheques to the Prince of Wales fund. On February 11th, 1915, Boyton raised £3 17s. 10d by organising a concert in the school rooms.

Over time various houses were made available to the families throughout the area. One of the biggest problems being faced though, was one of language which at first proved to be a barrier. It was also difficult to keep extended families together within the same area. One distressed family being placed in Stoke Climsland found their mother-in-law being found a home at Bridestowe. The Rev. Charles Kite of North Petherwin took in Madame Wigny and her son, with the costs being bourn by the parish and neighbouring parishes. However, given Madame Wigny’s health and her former position in life, the Launceston Committee saw the necessity of making extra arrangements for her comfort which entailed extra costs. The Belgians soon became important members of the community right up to their departure on January 25th, 1919. As well as offering this refuge, the town and surrounding parishes raised a total of £2,497 to help the Belgium families who came to the town with very little of their own possessions. Over the 4 years, the Belgians were also able to find work, earning a combined wage of £709.

Article from January 1915 on the Belgium Refugees

Belgravia War Hospital Supply Depot.

The old British School building in Western Road was first mooted as being an ideal building for a barracks but was eventually utilised for the war effort as a branch of the Belgravia War Hospital Supply Depot, begun by Mr. A. S. Cope and whom acted as its hon. secretary until he left the area in January 1917. Here 18 female and 16 male workers manufactured crutches, bed cradles, and knitters. Launceston was also at the forefront of women helping to replace the men in agricultural.

Women and the War Effort.

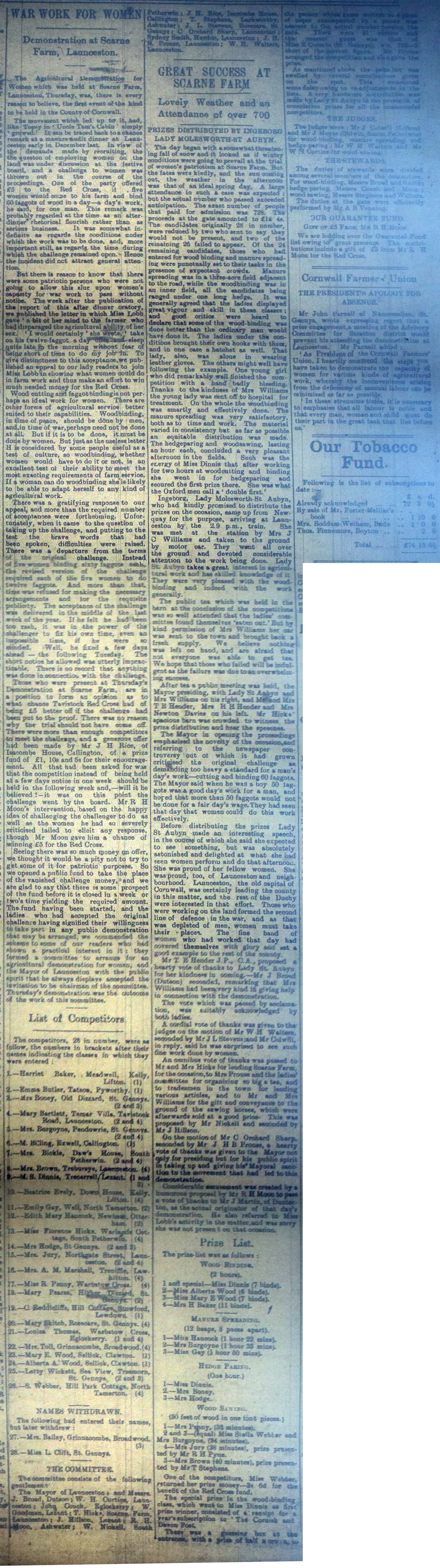

At the Launceston, Camelford, and Stratton District War Agriculture Committee meeting held on Tuesday, January 25th, 1916, a recent survey of the parishes to assess whether women were willing to work on the land showed a surprising number that had put themselves forward. However, there was some dissenting voices. At the Chemical Co. annual manure audit held at Homelands, Lezant, Mr Dymond of Stoke Climsland, said he thought the ladies could do more good in looking after the household. “It was not what a man got, but what a woman saved, that made the difference” he said. “How could they keep the house going and be out on the land?” he asked. In the discussion which followed it became quite evident that the majority of farmers present were not in favour of employing woman on farms.

Mary Francis Vivian Lobb being a strong advocate for women to help out in agriculture, was keen to show that women could take their place and help the countries growing need to produce more of its food, especially with the drain on man power to the war. Lady Molesworth St Aubyn was another tireless campaigner and as early as 1916 she helped organised exhibitions showing the aid women could provide to the home front. These took place at Thomas Hicks’s farm at Scarne Farm on March 9th, 1916. Those that took part are: Mary Francis Vivian Lobb, Treguddick, South Petherwin: May Billing, Exwell, Linkinhorne: Miss MS Dinnis, Trecarell: Louisa Thomas, Warbstow Cross: Harriett Baker, Meadwell, Kelly: Mary E & Alberta A Wood, Sellick, Clawton: C Reddicliffe, Hill Cottage, Stowford: Letty Wood, Sea View, Tresmorn, St Gennys: Emma Butler, Tatson, Pyworthy: Mrs Burgoyne, Pendowrie, St Gennys: Mrs Hodge, St Gennys: Mary Bartlett, Tamar Villa, Tavistock Rd: Mrs Jury, Northgate St: Edith Mary Hancock, Newham, Otterham: Emily Gay, Well, North Tamerton: Mary Pearse, Higher Dizzard: Mrs Bailey, Grinnacombe, Broadwood: Mary Skitch, Rosecare: S Webber, Hill Park Cottage, North Tamerton: Mrs Toll, Grinnacombe: Beatrice Evely, Down House, Kelly.

These four images were taken at the 1916 Scarne Farm demonstrations held on Thursday, March 9th, organised to show the skills of female labour and how they could aid the war effort.

The King’s very own farm at Stoke Climsland was at the fore front of hiring women to fulfill the role left by the men departing to the front. More.

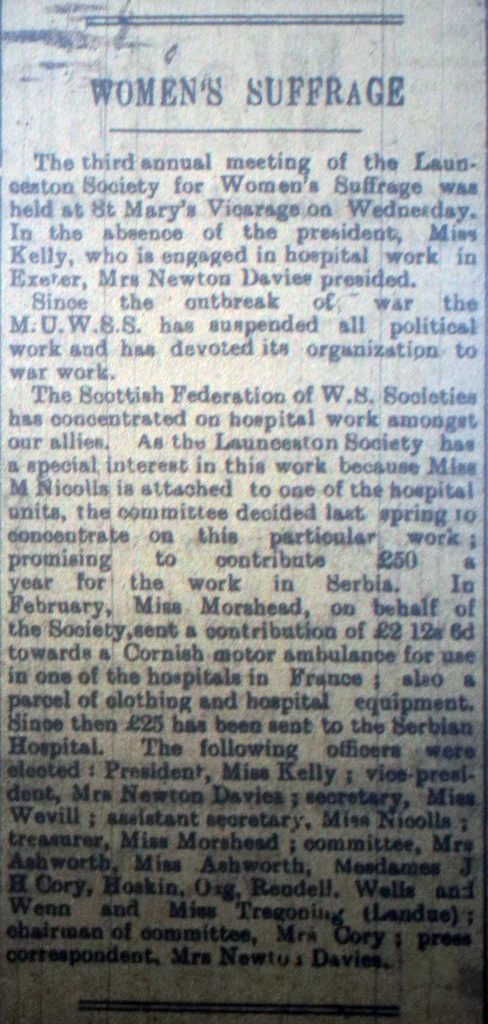

The Women’s suffrage movement that had gained momentum in the years leading up to the war, was one of the casualties of the war, with all political action being suspended. However, the cause was never far from the mind with activist continuing to hold meetings. The Launceston Society for Women’s Suffrage held regular annual meetings throughout the duration of the war. Many of its members were themselves away performing their own war work such as the Societies president, Miss Kelly, who was engaged in hospital work in Exeter. Another member was pharmacist Marion Nicolls, who volunteered to work for the Scottish Women’s Hospital led by Dr Eleanor Soltauwas in Serbia. Marion along with everyone else was taken prisoner by the Austrian’s in 1915 and released in January 1916. Due to Marion’s work in Serbia, the Society promised a figure of £50 per year for the Scottish Women’s Hospital’s work in Serbia.

In Enemy Country.

It wasn’t just at home that the outbreak of war impacted on people. The brother of Launceston businessman Nathaniel Reed, found himself and his family cut off in Germany as the hostilities broke out. Courtney Reed was staying at the Kaiserbord Hotel, Aachen and in the September 12th edition of the Cornish and Devon Times he retold his families story of how they escaped Germany. The full story. Mr and Mrs A. H. Grigg, of Bank House, Westgate Street, Launceston, also experienced a trying time on their return from Switzerland. They were with a Polytechnic party and had had a very pleasant holiday amid the Alps. Amongst other places they visited was the very Mulhausen in Alsace that just a few days later was occupied by the French, after sanguinary scenes in which 45,000 men were killed or wounded. Mr and Mrs Grigg, along with the Polytechnic party, left Lucerne at 9 p.m. on Friday, July 31st, on their homeward journey by way of Ostend, little thinking what was before them. It was the eve of the war where Germany after declaring war upon Russia, without warning in their advance to fight France, invaded Luxemburg. All went well until the train reached Basle, where the party were due to change for Ostend. To their amazement, they found that they were absolutely cut off from proceeding to that direction. The state of affairs becoming understood, there was a general rush for the train that was leaving for Paris. So great was the crowd of returning tourists that the train could not take them, and many were left behind. Mr and Mrs Grigg were fortunate to secure places in the departing train. After passing the frontier, and when near Belfort, they were alarmed to hear three loud explosions at intervals; and the train was brought to a standstill just as the last one went off. Mr Grigg did not know what happened. It sounded like the explosion of bombs. Such was the force of the explosion that all the windows of the compartment where the Grigg’s were sitting shook and trembled, and the passengers were thrown in confusion. One lady of the Polytechnic party was so affected that she died on the spot. The train being stopped at Belfort, the passengers were ordered to detrain. Mr Grigg’s impression was that the line had been cut. Belfort was the location of one of the strongest fortresses that France had, pointing like a sentinel to the lost provinces. Troops were everywhere. All the way to Paris the countryside was alive with camps and troops. Troops singing the ‘Marseillaise‘ crowded the trains going to the front. The Grigg’s and their party had an awful time on their continued journey to Paris. Finding no room in the compartments, they had to stand with many others huddled in a corridor, taking turns in sitting down on luggage. There was neither food nor drink to be had, and the heat was insufferable.

Paris was reached at 11 o’clock on the Saturday morning. The city was in a turmoil; the problem was to get away as soon as possible. There were two difficulties; one was excess demand over the supply of train accommodation available; and the other was want of current coin. Mr Grigg had managed to cash a cheque at Basle, but the Swiss paper money that he received in exchange proved to be worthless after leaving Basle. So the Griggs found themselves in Paris with just two English sovereigns in their possession. However, a fellow traveller with the Polytechnic party offered them a loan of £5, which they gratefully accepted. The return tickets via Ostend were useless; and fresh fares had to be paid to London. Again great struggle for places in the train ensued as the tedious journey set off for Calais an hour after they had arrived in Paris. They were relieved to finally reach the coast and step aboard the crowded passenger steamer where Mr. Grigg was at last able to secure some refreshment in a bottle of soda water, their first such since the previous evening other than a small sandwich which had been distributed in small pieces to some of the party. The party eventually reached London at 10 o’clock on the Saturday night and after a few days rest returned to Launceston.

Experiences of the Front.

Back on the front many of Launceston’s serving men were now writing back of their experiences fighting, relaying in heavily censored letters, the devastation and suffering that modern warfare was inflicting on the land and it’s people. Sergeant Douglas Cavey serving with the Medical Corps, wrote back to his family on September 16th, 1914; “You see my address still keeps changing. As you know I started out with the First Field Ambulance, and then got attached to No. 9 General Hospital, which has been taken over by No. 2, No. 9 having to go further on. My adventures have been many. I have been to the front, done a lot of marching, and was still on the go when I was sent off with a lot of wounded and sick, and in the end got lost; hence my many changes of address. It is quite on the cards that I shall be reported as missing. If so, you will know that I am safe and sound so far. I am keeping fine, simply A1. I have written a number of letters home, but I expect none have reached you. I have not received any letters from home since I left England.” He signed of by saying “all will end well for England, and the Allies will be victorious.” Sergeant Cavey went on to see much action tending to many wounded and sick men. He was still serving with 9th Field Ambulance who were part of the Guards Division when he was struck by shrapnel from a nearby shell burst whilst helping to clear battlefield causalities in France on August 30th, 1917. He died of his wounds the same day.

Motor Driver Tom Parsons of the Army Service Corps (formerly an apprentice at the Cornish and Devon Post) wrote home in length in mid November of his experience of the retreat from Mons in the previous August/September. He said “I might say I never saw such a sight in my life-to see our troops, beaten to the World, but all happy as they passed through. The sun was scorching. We passed from Lavell on to Landrecies, where we had to halt owing to some of our park taking the wrong road. I shall never forget it as we all got together and moved off again in the direction of St Quinten.” He continued, “We had got two miles from this place when we were stopped by a scout, who said the Germans were coming across our front. We had to turn around, and God only knows how we did it, as the road was so narrow, and to make things worse had a rail track on the side of it. But we did or at least all but four of us. I was one of the lucky ones to get round, and back we went again for Landrecies, which we had only just left quite happy.” “Oh those two miles seemed ten to me, so we could not move for refugees who were in vans pulled by oxen, and women and children in handrails. I was driving, my other driver being on top of the van with his rifle.” Tom the told the story of a girl refugee shot in the cheek, “I stopped and picked up a little girl and her brother who were crying bitterly for mercy and we got back to Landrecies quite safe, but had not been there five minutes when a rifle went off and the bullet grazed the cheek of the girl I had taken up. She bled very badly but was soon attended to by one of the Medical Corps.” He then admitted to not feeling very comfortable at that moment, “and I did not mind much what happened to me just then. I think it was a very lucky thing for us that there happened to be a lot of our troops about, so we were well covered moving off again.” Tom then explained that he drove away again from St Quentin, passing through Ham, and on to Meux. “We were called out at midnight, and I remember it, as I had not been lying down more than an hour. From here we moved on to Meluin, where we had a glorious three day’s rest, and then we got on to Quiney, close to Aisne and Scissons, where we had to work very hard fetching ‘medicine’ for the Germans from (censored word). Noght and day this lasted for three weeks, when we were relieved and sent back to (censored place) for a refit.” He concluded this letter with “Now we are at it again somewhere in Belgium. I can tell you this job is not all ‘beer and skittles,’ but I am proud to be one of the boys of the old town to be doing my bit towards victory.”

Driver James Avery, of the 23rd Battery R.F.A spoke of his experiences to the Cornish and Devon Post when he returned home to convalesce on October 23rd, 1914:

Driver James Avery, of the 23rd Battery R.F.A., who was wounded in the battle of the Aisne, and has been in hospital at Plymouth about a fortnight, arrived at Launceston on Friday last. He looked remarkably well, and jocularly remarks that he has been ‘fattened’ whilst in hospital. He took part in the battle of Mons, and in that wonderful retreat to within a few miles from Paris, which is described as one of the greatest military achievements ever know.

SHELLS IN JEWELLER’S SHOP.

He left Launceston, he said, on August 5th (1914) for his headquarters, arriving there in the evening, and sleeping with 500 others in the Square. He joined his battery at Bulford, and after a few day’s training left for Southampton en route for France. They went by train as far as Arras, and then marched to Mons, where they arrived about 9:30 on Saturday evening. bout 4:30 the next morning they were in action. He had his baptism of fire in an orchard close to the town. The Gordon Highlanders came to relieve them, and their charges on the enemy, says Driver Avery, were magnificent. He had a horse shot under him at Mons, and also got hit in the thumb, the sensation, he describes, as being similar to a bee sting. The Germans did not like the bayonet, he remarked, and shrieks could be heard when the British were coming towards them. The enemy, however, were in overwhelming numbers and Driver Avery’s battery had to retire to another part of the town, close to the Middlesex and Lincoln regiments. They fought well, but suffered very heavily. Driver Avery was close to a jeweller’s shop, when shells from the German guns smashed everything and knocked the jewellery into the street. The enemy were as thick as ants, and the British retired through Ham and St. Quentins and for four days the fighting was practically continuous. The sound of the guns was terrible; thunder could not be compared with it, and several of the men had become deaf through the great noise.

THE ‘POST’ WELCOME.

Whilst having had a little rest at Cambrai, Driver Avery receieved a ‘Cornish and Devon Post,’ and “you should have seen the crowd around me” he said “at the sight of a newspaper.” That single paper was read by hundreds, both men and officers, and handled until the print was hardly readable.

FRENCH WOMEN HELP TO DIG TRENCHES

The British retired to within 15 kilometres of Paris, but during that retreat they fought well and put every obstacle in the way of the Germans. The bridge at the beautiful town of Meux was blown up, and when they got sufficiently far away from the enemy, trenches were dug, perhaps not very deep, and they were sometimes helped in this work by the French women, who did all they could for the British soldier. Driver Avery speaks very highly of these women, who would provide the Britishers with food on their march, giving them ducks, fowls, hares, in fact, anything they had got, knowing, of course, that if ‘Tommy’ did not get it, the Germans would steal it in their pursuit. These women also brought water for the horses, so eager were they to show their gratitude to our army.

NO YOUNG MEN LEFT.

Where they could, the Germans drove these people before them, compelling the British to try and attack the enemy in the rear. These actions have been most costly, but it made our boys blood boil. They were very determined to get to grips and would not give in until utterly forced to. If their feet got sore with marching, they used their putties as bandages and walked in this way. Villages were very close together, but the inhabitants consisted solely of women, children and old men. Driver Avery alluded to the terrible sights he had seen of people leaving their homes; those who could not walk being driven away in wheelbarrows. Children were often taken care of by the British soldier. Driver Avery himself carried a child for miles on his horse with him to a place of safety, and shared his food, which consisted chiefly of bully beef and biscuits, with it. At times they had no idea what day it was, or where they were, the names on the signposts for some reason being obscure. It was a beautiful country, and every bit of available land was cultivated.

SPIES MADE SHORT WORK OF.

One evening, evidently thinking they were quite safe, Driver Avery, with 400 or 500 others, were having a ‘sing-song’ as he said, and a smoke in a filed, when to their surprise, they were informed of the enemy’s presence by a shower of lyddite shell coming amongst them. “So we had to again set to work,” he remarked, “after some had been killed.” They had been plagued a good deal with German spies, who had been very daring in their exploits, but once found out “short work was made of them.” The Germans, in addition to burning villages, carried away furniture, bicycles, and anything they could lay their hands on.

A HAUL OF MOTOR CYCLES.

On one occasion a German motor lorry was seen going across the country about two miles distant. Attention was given to it by the guns, and the lorry was damaged to such an extent that it could not proceed. On inspection it was found to be full of motor bicycles, which, of course, became useful to the British. At other times, vehicles were captured loaded with furniture.

VILLAGES IN FLAMES.

The scenes witnessed in the advance towards the Aisne almost baffled description, but the French endured the hardships bravely, even when they returned ad found their homes in ruins. Villages were in flames, and to get the horses to go through, bags had to be thrown over their heads. Plundered bicycles, which the Germans had left in their retreat, were found by the roadside, and motor lorries had been driven into ditches, and damaged, and others burnt, so that they should not be used by the British. Several, however, were fitted up by the engineers, and a large number captured in this and other ways were now being used to advantage. Empty wine bottles and broken furniture were also a common sight. The latter was used by the ‘Huns’ as barricades, and passing through some places the streets had to be cleared before the horses could pass.

FIGHT IN MID-AIR.

Driver Avery said it was wonderful what amount of information the airmen would glean, the accuracy with which they could tell of the enemy’s position, and the approximate number of troops. He has seen a fight in mid-air between a Frenchman and a German, and after some fine manoeuvring the Frenchman managed to soar over his opponent and bring him to the ground with a pistol. The British officers had acted gallantly throughout, he said, and would not order their men to go where they would not go themselves. They had had torrents of rain. On the 14th September he had the opportunity of seeing the Devons going into action, and a fine lot of men they were. When in action, we seemed, says Driver Avery, those heavily in horses, the object evidently being to prevent our men from getting their guns away in case of attack.

FORTUNATE ESCAPE.

Whilst in action in the battle of the Aisne, Driver Avery was fortunate in escaping as lightly as he did. His two horses, the one he was riding and the other leading, were both killed, and he was hit in the leg by a bullet. He fell, the horses rolling on him, and he lay in this precarious position for eight hours, being unable to extricate himself. He was pinned to the ground for a whole night, lying in blood, and with the guns roaring all around him. Asked how he felt, he said he had plenty of company – both dead and wounded. When discovered by the Army Medical Corps, the heel of his boot had to be taken off in order to free him. He could not walk, and with 30 or 40 other wounded was taken to a private residence. This proved to be only a temporary resting place, for the Germans soon began shell it and he with others had to be taken across the pontoon bridge. He was conveyed to the base, and afterwards brought to England with other wounded soldiers. On landing at Southampton they were met by thousands of people, who gave them a hearty welcome. At the hospital at Plymouth they had every attendance. Gifts came from all directions and they had the luxury of cigarettes. In France the soldiers had to resort at times to tea leaves, clover buds, etc, to get a ‘whiff.’ Our men are best on getting souvenirs, and Driver Avery procured among other things a German cup, which was exhibited at the recruiting meeting at Launceston on Tuesday. Driver Avery leaves Launceston again on November 7th.

The logistical problems of getting the mass of correspondence to and from those serving on the front was highlighted by Sergeant R. R. Warren a former postal worker at Launceston before the war. In an article in the Cornish and Devon Post of October 3rd, 1914 he laid bare the many difficulties:

Sergt. Warren has his offices in the Chamber of Commerce and his dining room in a theatre! Work apparently goes on on Sundays without interruption for, writes Sergt. Warren, “it is not a bit like the Day of Rest. We have had a very busy time yesterday we had 42 sacks of mails….. Some of our fellows are missing, and they have a difficulty in keeping the field post office supplied.” German helmets and other trophies are eagerly sought after, Sergt. Warren’s corporal being successful in securing one. “People flock from everywhere to see the English soldiers, and the place is like a fair, people coming from miles around. We close the office at four o’clock and open at 6 to 8. They have no tents here at present, so the men have to sleep in the open. It is not so bad whilst it is warm. “We get plenty of tomatoes as 1d. per lb, and plenty of pears. No fish since leaving home. Although we live well, there are many things we miss. Could do with some French beans!” “A party of Gordons who escorted the German prisoners from the front brought in three sacks of mails returned from regiments. The mails were for the Gordons, who were either killed, wounded, or missing.” “Looks as if the war is going to hang on a bit…. Some of the Garrison Artillery from Crown Hill have arrived. Thought B.B. (a local man) might be there….. South Africa is not a patch on this war (recounting his time during the Boer War). I have had some harrowing tales from some who have returned from the front. We have lost a consignment of one million cards. The supply stores are a sight to behold. Boxes of biscuits, bacon, tea, bully beef, tobacco, flour; tons of everything. It is marvellous how the supplies are arranged……. The whole of the staff at this base is working at high pressure.” Even when close to the seat of war, amusing incidents will happen, and Sergt. Warren has tumbled across a few. He says: “Had a funny experience yesterday. When passing along outside our headquarters three young ladies with their sweethearts passed and asked for my R.E. shoulder badges for souvenirs. But not being able to understand them, could not put them off. Could not speak French and could not make them understand. At last I told them to take them off. This they quickly did!” “They thereupon said ‘Kissey me’ and I stood aghast! But the young fellows endeavoured to assure me that it was quite alright and was the custom in France. I reluctantly obliged the girls by kissing them in the main street in broad daylight! This is a funny country and people are quite different to our English folk….. I have had to hold letters for 48 hours.” “The Highland regiment stationed here goes out for route marches, and the pipers and drummers create quite a stir amongst the people. They cannot understand the kilts and are anxious to know whether the ‘Scotties’ wear anything under them!” Sergt. Warren, speaking of the arrangements made for some of the men, said at first there were no tents and water had to be carted in barrels. They were laying two miles of pipes to carry water to them. “We have had a terrific thunderstorm,” he says, “and such lightening I have never seen in my life.” “An officer came in today asking for special service cards, and I recognised him as Captain Roney Dougall, who was secretary of the National Service League at Launceston. I said ‘Captain Roney Dougall?’ He replied ‘Yes, how did you know me?’ So I told him I came from Launceston.” “I looked out of the window about seven o’clock this morning, and saw 1,200 prisoners going aboard a ship. I think they send them to England as far as I can gather…. Things appear to be going well at the front, and I hope the war will not be so protracted as at first surmised.” “One can quite understand an army requiring so many horses when you see the boats of gun waggons, etc., brought into this country. The horses are the admiration of the French people and it is inspiring to see hundreds of them paving on their way…. All the time we are so cheerful, whistling and singing and the French people cheer in return. The favourite phrase is ‘Are we downhearted? Whereupon the whole yell out ‘No’… The whole affair is being engineered with a degree of secrecy never before attained.” “Jacl Jackson was passing through here recently on a motor tour. I saw him and shook hands with him. He is very fine fellow.” Sergt. Warren says that thousands of letters are insufficiently addressed and never reach the people for whom they are intended. This should be noted by our readers. On the last day on which he wrote, Sergt. Warren says that twenty tons of gifts had just arrived from England, but from what he could gather the men would rather be sure that their wives and families were being well looked after at home.

Driver A. Lillicrapp complained in a letter written home in November 1914, “It will be a blessing when this war is over, for I have seen enough of it” he said, “what with towns blown to bits and people leaving their homes carrying a few things under their arms or pushing it along in wheelbarrows.” Another letter written home by Tom Parsons at the same time from was so heavily censored that only the statement that he was quite well and “I have not heard from you lately,” were the only discernable parts left to the reader. Gunner W. H. Broad from Lifton who was serving in the “E” Battery, Royal Horse Artillery, in a letter to his Aunty thanked her for a parcel containing socks that she had sent him. “They fit a treat and we are so glad to get them as it is very cold here,” he told her, “Things out here are just about the same; plenty of shells and bullets flying about, but it can’t last for ever. A lot think the war will be over by ‘Xmas.” In another letter sent a few days later he continued with his optimism at the likely end of the war “I think our hardest work is done” he said. The date, November, 1914.

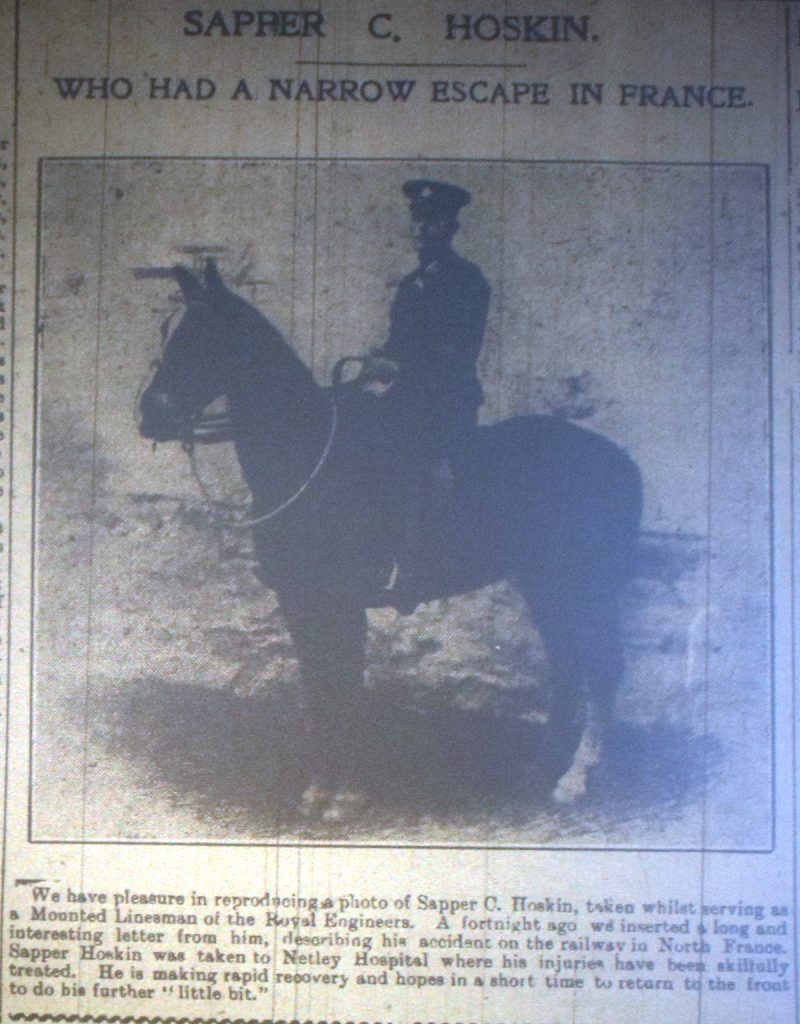

Sapper C Hoskin, November, 1914

Writing a letter of thanks on Tuesday, December 28th, 1915, to Messrs. Hayman and Son for their supplying a concertina to him, Private William J. Braund (Regimental No. 17976) of ‘A’ Company, 7th Battalion, D.C.L.I. (formerly an employee of the Cornish and Devon Post) had this to say: Please accept our grateful thanks for your splendid gift of a concertina for our Section. It arrived quite safe last night, and I unpacked it amidst anxious faces. It is a lovely instrument and our first tune was ‘For he’s a jolly good fellow.’ and I would like for you to have heard all the boys in full chorus. We have been in the firing line during the Xmas, and I believe we come out again about January 2nd. We are only 180 yards from the Huns, and we sang and played a few carols to show them we were not downhearted, although we are not in the pleasantest of surroundings. To tell you the truth we are all like ducks in mud and water, so you will understand what a little music is to us. Your practical sympathy has shown the boys of our Platoon (and even our Company) that your heart beats for them, and everyone wishes me to convey to you their wishes that you and your firm may have a prosperous New Year. Again thanking you on their behalf.

Mr and Mrs J. Dew of Newport, Launceston received notification in January 1916 that their son, Private Reginald Dew of the Canadian Contingent, had been wounded in Flanders. Writing home he said: He was coming from the trenches to the billets, when a bullet struck him in the left heel just behind the ankle. After travelling about 300 yards, he stopped at a sentry post, and taking off his puttees, boots and socks found that part of the bullet was showing so that he was able to pull it out. The bullet looked as if it had struck the ground first. If it had not done so, it would certainly have gone through the heel.

Dr. Arthur Budd, (Launceston Doctor) a Lieutenant with the 41st Field Ambulance, R.A.M.C., 13 Division, M.E.F. serving at Gallipoli wrote back to friends on January 6th, 1916 detailing his experiences, which for him offered quite and exciting adventure no matter how horrible actual war was to him:

“All my work at present is in the trenches, dressing and attending to the wounded, whom I send on to the ambulance and clearing stations. My dug-out up here is just behind the trenches, with a little dressing station dug out in the cliff side and covered with sand bags for protecting. It is very exciting work up here, pretty ‘hot’ but great sport. The Turkish trenches are about 25 yards from our trenches. But in one part of the firing trench their trench is only within six yards of ours, so you can imagine one has to be very careful to keep well down below the sand bags parapet. The trench is so near that our Tommies throw their empty bully beef tins over into the Turks trench, and ‘Johnnie Turk’ throws his into ours in return. I watched the bombers for some time today sending over bombs from a huge catapult and watched the results through a periscope. Several Turks, or pieces of them, frequently could be seen being blown up into the air. This was in return for some damage their bombs did to our men in the morning, when, I am sorry to say, we lost several of our men. One Turk who was evidently tired of German company, came over the other night and gave himself up a prisoner, with hands up, and I have got his bayonet, which I shall try to send home, as it will be a great curio with its Turkish markings and half moons on it. A day or two ago they kept on putting up a dummy dressed up like a Turk, making out to our men it was one of them and enticing them to fire. Fortunately for us, they put it up too high- above the parapet of their trenches- and we could see the broom handle or whatever it was that it was mounted on. They have not sent over any gas lately, but we always carry our gas helmets with us when in the trenches, by order. Then part of my duties just now, too, are to see that the trench we are in is kept in a sanitary condition, and you have to be very careful about this in the trench, as if not, you would soon get still more struck down with disease. There are special men for all this sort of work called ‘Pioneers.’ It is all very exciting, but it is very noisy, of course, as the firing goes on all day and night, but somehow one gets use to it. One never possibly gets an undisturbed night up here and always gets called up to dress wounded many times a night, so I don’t undress at all, in fact one is not supposed to. I get a nap or two in the day when possible. I often wonder how things are going at Launceston. I think I told you in my previous letters I had received some letters from many kind friends from home, and one of your parcels has now reached me, so I am hoping the rest you speak of will turn up soon. You should see us all over our parcels, from the Colonel downwards, like a lot of schoolboys enjoying themselves with their tuck boxes. You have no idea what pleasure it is when we get a letter or parcel mail. It was a treat to get a home made cake, etc., as of course on active service the diet must necessarily be plain, and chiefly bully beef, but we always get plenty. I am keeping very fit and well, and I really never thought I should keep so well when I first saw so many going down with illness.“

During the course of his letter Dr. Budd made reference to ‘our exciting departure from Suvla Bay’ and what happened after; but this was omitted from the report but was later reported on, on March 4th, 1916, where Dr. Budd thanked the editor of the Cornish and Devon Post, Mr. Orchard Sharp, for the gift that was sent out at Xmas of 100 pipes, which had been handed out to the grateful men. “Please accept the very best thanks of the men of this ambulance and myself for the kind present of pipes, tobacco, etc, which we have received safely,” he said. “We are one and grateful to you and your readers for your kindness. I need hardly say that they were very much appreciated by us all and I thank you on behalf of my men for your kind gifts,” he added. He then went on to report on his activities of the last two months: “We have had a quite exciting time the last two months as this Ambulance took part in both evacuations of Suvla Bay and Cape Hellas and were practically the last off. I could tell you a lot, but censor forbids. The whole (censored) Division . . . . . . .We are at present resting and re-equipping and in about another week expect to be sent to Mesopotamia, when we expect we shall be kept pretty busy again. It seemed quite tunny to be away from the noise of shelling after having been in it continuously for three months. The climate out here is lovely just now and a treat after the rough weather we experienced with the blizzard in the Gallipoli Peninsula. We have just re-equipped our men with summer clothing and helmets and they look quite smart, but we looked very shabby when we arrived here I can tell you, as we lost nearly all our belongings to the evacuations.“

Dr. Budd again wrote back to his family this time aboard a Troopship on February 12th, 1916:

“We embarked at Suez, and have been at sea a week. We are on our way to Mesopotamia and in a few days or so expect to be in the thick of it again. We shall be at sea about another week, and shall be pushed right up to the front again. This is a very fine ship of 12,000 tons. We have nearly 3,000 troops on board, and about 60 officers in the mess. The (censored) Regiment are also on board. They have their own regimental M.O. We are having a very good time, and the days seem to fly. My mornings are mostly taken up with sick parades and inoculating the men, which takes us time, as we are about 1,000 strong. In the afternoons there are sports for the troops which one helps in. Then the inspection of the ship and mess food all takes time and so the day flies. We go right up the Persian Gulf and expect to be landed at Basra and encamp for a short time on the banks of the Euphrates or Tigris rivers and then go right up, in hope to meet the Russians! I am very glad to begin this Mesopotamia campaign. The health of the men on board is fairly good. I get a sick parade of about 50 every morning with different complaints and have several in hospital. We have a very good little hospital on board, right up on the boat deck. I have my own staff which is composed of 1 Sick Sergeant, 1 Corporal, 4 Dresser Orderlies, and 16 Regimental Stretcher Bearers. I have to give them lectures on Nursing and Bandaging, etc. We have a swimming bath on board and get lovely bathes every morning before breakfast. Reveille goes at six, and physical drill at 6:30 for the men. I join in sometimes for this, as it is good exercise and helps to keep one fit. but it is optional for us. All the ship’s officers are Naval men or Naval Reserve and the three officers mess with ours and the ship’s Captain takes one end and the Colonel of the Battalion the other. Hope all are well at home, etc.!

After arriving in Mesopotamia and being just a few miles from Kut, Arthur wrote back on August 2nd, 1916:

Just a few lines to let you know how things are going on. I daresay you may have heard that our ….Division were sent from the Gallipoli Peninsula Campaign to Mesopotamia as relieving Forces for the relief of General Townshend. We had a quiet but interesting time coming up the river Tigris, passing through many historical places of interest. It was very slow work coming up the first few hundreds of miles, for owing to the shallowness of the river the troops had to be brought up river in comparatively small steamers; then we drew into the bank of the river every night and encamped and did the cooking for the men’s food for the day. One night we camped in the original ‘Garden of Eden’; but there were no apples to be seen, however. Other nights we encamped at Sodom and another at Gomorrah. Beyond their Biblical interest I have little to say, for they are about the most god-forsaken places you could imagine and mere deserts. Our real hard had commenced after we had travelled several hundreds of miles up the Tigris, and after heavy marching night and day we eventually reached the Front, where we relieved the ….Division for the final push to try and relieved Kut. We knew towards the end how many days more Townshend could hold out, which made things more exciting and at the time of the fall of Kut we were only eight miles away. We had some very stiff fighting the last few days and fought four battles in nine days. So you can imagine I was kept very busy. Unfortunately, this regiment lost pretty heavily in the last engagement, both in men and officers.

We were all very disappointed of course at not obtaining our object, but the Division did well, and we see the papers at home speak highly of our efforts, and talk of us as the Iron….Division from Gallipoli. As M.O. of a regiment you get a more exciting time than when at an Ambulance, for you are with the Battalion all the time, and, with your Medical Orderly, follow up the Battalion in all their attacks and charges and attend the wounded as they fall and are exposed to shell and machine gun fire all the time. I will merely add that I am extremely fortunate after the last engagement to be here and able to write this letter today. I often wonder how things are going with you all at home, and Lanson must be almost depleted of men of suitable age by now. The women are doing wonderful work, which will all help to terminate this bloody war. I was very interested in reading in the Cornish and Devon Post the agricultural demonstrations at Scarne by the women. One cannot overestimate the valuable work women are doing. We all rejoice at the victory of our navy off Jutland, but of course the news would be very stale to you by the time it reached us. I trust you are keeping well yourself. I am glad to say, so far, I have been fortunate enough to keep un excellent health myself, for which I am thankful, for at times my work has been very, very heavy, long hours and sometimes after engagements working night and day getting the wounded evacuated. At present, we are having a quieter time and have been relieved from the firing line, and we are away back a little.

Sickness is plentiful among the troops for this is a very trying climate with the terrific heat. The temperature daily now is 120-126 degrees in the shade every day. Fortunately, we get cool nights, the temperature falling to 75-80 degrees which is our saving. We get all sorts of disease to deal with out here – cholera, malaria, heatstroke, sandfly fever, heat exhaustion as well as snake bites and other such aliments. At present there are about 2,000 sick from one cause or another in the Field Ambulance. Well, I must conclude this now. My kind regards to all friends at Lanson and with the same to Miss Sharpe and yourself.

Arthur continued his communications from Mesopotamia the following March, on the 1st in 1917:

We have been having a most exciting time the last few days, but on the other hand a very strenuous time, but are all very fit and well; and our continued successes compel us to keep the enemy on the move; after each fight we are following them up. We have had some very stiff fighting this week, and have utterly routed the enemy, while our navy on the Tigris has done splendid work in conjunction. We are all in great spirits today, for yesterday our monitors re-captured the monitor “Firefly,” which the Turks took from us in General Townshead’s time. Also our ship “Buara,” with 1,100 prisoners and the monitors sank the Turkish flagship yesterday. The Buara’s 1,100 prisoners were all wounded prisoners and also another barge with 800. It is all splendid and we are all a keen as mustard to push on to get more, and annihilate the Turkish army. The total enemy killed, captured and wounded is roughly estimated at 15,000 up to date. So you can imagine what fighting we have been through. You will have heard by now that we have taken Kut, over which the Union Jack flag is now flying. We have now left Kut far behind and are a long way further up. We are doing as much as 15 to 20 miles a day and at night just lay down anywhere. We have our blankets, and my old pal, the “sleeping bag,” goes with me everywhere, so we keep warm, and rig up little bivouacs to keep the winds off. We get water from the river, which I have to chlorinate for the battalion before use.

We pushed on here yesterday after fighting, and terribly punished the enemy. I had to stay behind with armed mounted escort to attend and treat wounded Turks we picked up on the way, who had been lying about wounded. One wretched Turk had one leg blown off and half another foot. It is marvellous how he lived untreated for so long. I caught up the battalion later on. I am glad of my horse in these long marches, and am so fond of him. It is surprising how they get used to the noise of the guns. We have captured 21 large guns, so far, from the Turks since the present operations began. I am awfully fit and well, and love the excitement, and this rough life seems to suit me. Our food is just bully-beef and biscuits and tea at present, but plenty; we get a good feed of this when we get in at night. Goodness only knows when we shall get any letters again and parcels, but they will bring them up the river as soon as possible, for we are pushing up the enemy so fast, and are pushing on to Bagdad. You wil understand how difficult it is to write under these present conditions. I am sitting now in a crump-hole (shell-hole) writing this, and we are just off again.

Whilst on leave home at Egloskerry in February 1916, Private John R. Symons relayed his experience in the firing line in Flanders. After emigrating to Canada 1912 he enlisted with the Canadian Infantry in September 1914. After five months training he was transferred to England and later to France, where he had been involved in the many battles that had taken place. During his ten months in the firing line the only injury he had sustained was a bruised arm, caused by a blow from a German rifle whilst on patrol duty during the night. He explained that he was part of four Canadians on a night patrol when they came across a patrol of six Germans and in the skirmish that followed John received his injury, but the Canadians patrol were able to account for the German patrol, after which they beat a hasty retreat as the German machine guns ‘commenced to speak.’

On October 7th, 1916, Gunner Sidney P. Wenmouth of the Tank Corp (Regimental No. 200948) wrote back from hospital where he was recuperating from his wounds sustained in battle: ‘My wounds although numerous, are not severe. In our second action about a week ago the Germans simply rained machine gun bullets at me, and, unfortunately, some pieces caught me in the hand, arm, and back. I had a very near escape, for when coming back through a trench on my hands and knees after being wounded a huge shell burst about a yard back outside the trench, and for some time I was buried underneath a lot of earth, and had to be dug out. After having arrived at a front dressing station, I came back with two stretcher bearers and another wounded man. A shell burst behind us, killing the rear stretcher bearer and the man on the stretcher. On the whole I have had some wonderful escapes. We think we are doing a good work. Our infantry are simply grand; the way they face death is astounding.‘

The Lewis Gunners by Mark C. Tremlett, (Regimental No. 315931) 86th Prov. Battery.

It is an interesting thing

To know about this gun,

For when it comes in action

It makes the Germans run.

You form up into a line

Until your orders come,

And when the signal’s given

You lay down beside the gun.

As Clarke and Rowe are one and two,

To them the range is given,

Taylor three and Tremlett four;

Now you boys just listen.

Then you hear the word ‘Action,’

So now is the time to run,

Then you lie down on your back,

And crawl up with the gun.

One and two are with the gun,

Number five is William Dunn,

With ammunition he supplies

To end those dirty German lives.

Canny C. our team is called,

That’s Sergeant Higman’s crew,

We do our work as you know,

So that is nothing new.

As Quick and Vevs are one and two,

To them the word is given;

Pack up gun and do a bunk,

They do not stop to listen.

Selway three and Sydenham four,

Are just the boys we want,

Ayres is five and Wooley six,

That’s Sellick’s little lot.

Sergt. Barnes has got a team

But that is very small,

Pat and Harvey are the two

Who do the work for all.

Sergt. Adams has four men,

Pen and Gerry are two,

Roseveare three and Harris four,

That’s his little crew.

Writing home from a town in the Somme district, B.E.F. on November 21st, 1916, Launceston’s Baptist Minister, Rev. D. D. Bennetts had this to say of his experience of his voluntary work as a chaplain with the Y.M.C.A.:

‘I have been trying for some days to find time to write a letter; but the days have been fairly full, and when there has been a little leisure the surroundings have not readily admitted of settling to write in any measure of comfort. I left Launceston, you know, on Wednesday, November 8th, but I was not able to get my Military Permit and Order of Service in time to allow me to cross before Friday morning. On that evening I visited the Queen Mary Hut at Boulogne and conducted evening prayers there. On the following day, I travelled to (censored), and stayed until the following Thursday mid-day. It was there that I served what I may call a kind of apprenticeship in the supply department of the work serving the men with tea, eatables, and many little necessities that are sold for their conveniences. The shops in the towns and villages charge very high prices for all these things: candles, matches, brasso, blacking, tobacco, buttons, and so on. In addition to this part of the work, there is the educational, recreative and lastly, but not least, the spiritual and religious. I have already heard two or three very instructive and interesting lectures; illustrated one by maps and the other by lantern views. We had also one evening by a humorous lecturer. In addition to regular evening prayers in the hut, we have a mid-week evening service. On Sunday’s, besides any “parade” services that are sometimes held in the Y.M.C.A. huts (as here), we have our Y.M.C.A. evening services. I conducted such a service on Sunday evening last, here at (censored). We had probably about a couple of hundred men present, and they all joined in the service very reverently. It lasted about 40 minutes.’

Most of the allied armies on the western front had Y.M.C.A. units attached to them for recreational, educational and comfort services. They had field services in France gathered round the “Y.M.C.A. Hut” concept. The main focus of the National Y.M.C.A.’s work during the First World War was the construction of more than 200 Y.M.C.A. ‘huts’. Soon these were a common sight in cities, towns, villages and at railway stations across England. They were also built close to the front lines of many battlefields and were often subjected to shellfire. The Rev. Bennetts returned to Launceston in the middle of February, 1917. He was asked on his return whether the war had made any difference to the soldiers in the matter of religion. He said he was not in a position to make comparisons; but he could say that the typical soldier was in this matter either one thing or the other. He thought when the boys came back from the front many of ‘our’ conventionalities would have to go down, or the returned soldiers would remain outside the churches. ‘They would want answers to big questions‘ he said.

He also relayed an interesting story of his time on the front paying a visit to the village of Beaumont Hamel, about half a mile from the firing line. He went there with a fellow Y.M.C.A. officer and a sergeant major to select a site for a Y.M.C.A. hut. As the village had been swept away by the guns, they had some difficulty in knowing that they had arrived at their destination. The enemy observed them, and possibly mistaking them for generals ‘honoured‘ them with a couple of shells; from which, under the guidance of the sergeant major they took shelter behind a hedge.

Private John T. Slade (Regimental No. 13776) of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, wrote home in May, 1917, thanking the committee of the Soldiers Fund for a parcel which was “very welcome to himself and comrades.” He added: “Your paper find’s its way out here to me every week, and needless to say I pass many a pleasant hour with its interesting contents, which keep me in touch with the old town that I am longing to return to.“

Three Years of War by W. D. of the B.E.F., France, 1917.

Three years of war yet not the end,

Together strife and sorrows blend;

Three years of turmoil, anguish, grief,

In vain men ask “Whence comes relief?”

_______________________________

Three years of terrifying rage,

All done in an enlightened age;

Three years of maddening suspense

We look and seek for peace from whence?

________________________________

Three years of bloodshed, awful, vast

And men as in a furnace cast;

Three years of pain and agony

And strain of nerve and energy.

________________________________

Three years of chastened, downcast hearts

Where all have played their various parts;

Three years of aches and groans and pains

Fast bound with links of heavy chains.

________________________________

Three years of parting and farewell

With hearts that overflow and swell;

Three years of awful hideous crime

All crushed beneath the wheels of time.

________________________________

Three years of devastating strife

An era of the human life;

Three years of every vice of hell

The hounds of death that shriek and yell.

________________________________

Three years of war – what triumphs won

From rising morn to setting sun;

Three years of war but victory looms.

Arise, arise, shake off your glooms.

______________________________

Three years of war – how much achieved!

Hold on brave hearts you’ll be relieved;

Three years of war but day by day

A brighter hope, more glorious ray.

________________________________

Three years of war, but ah! I see

A day with shout of victory;

Three years of war then you will raise

Your hearts in thanks and fervent praise.

________________________________

Three years of war, ensuring peace

And such a peace that war shall cease;

Three years of war but freedom free

And nations set at liberty.

________________________________

Three years of war, but not in vain

From high and low hear men exclaim;

“Three year of war its speeding fast”

“Thank God we know it is the last.”

________________________________

Three years of war, from shore to shore

With ages crowded in the roar;

Three years of war, far down the years

They’ll view these times with pride and cheers.

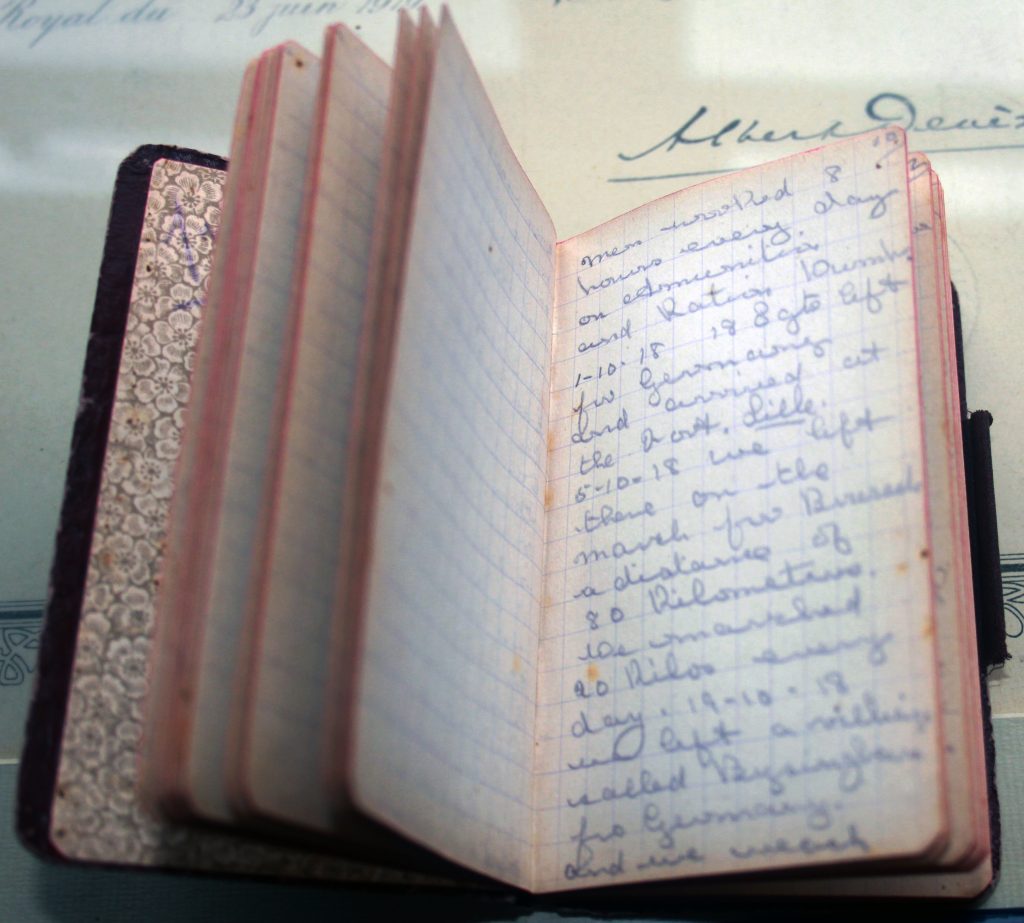

For some the war provided an experience that in a normal life they would never have gained. This letter which appeared in the September 14th, 1918 issue of the Cornish and Devon Post, shows the level of fascination that was on offer and a welcome distraction from the mundane life at being at war:

Lewannick Lad (Harry) Compares Jerusalem with Launceston, September, 1918.

Dear everybody, As you will see by the above address I have finally arrived in the Holy City and at present am having a rest in the Y.M.C.A., after a most trying and busy day. Of course Jerusalem simply bubbles over with interest and historic scenes and places, and you will be able to guess we have been “going some” when I give you first an outline of places visited to day. First of all, however, I must say we had a most interesting trip up here. The railway journey is not done in first class English railway saloons; but after all, the trucks in which we travelled didn’t bump so much as I anticipated. I need not say that I was unable to snatch much sleep, for if there is one thing I’m good at snatching, I think its the “old shut eye stunt” commonly called sleep. We took just 24 hours to do the journey, so you can bet we felt more or less tired.

The difference in appearance of the country was most apparent when the sun rose on the morning following the night ride. Instead of the perpetual sand, we were passing through grand fertile country where cattle and goats were feeding, where farming separations were in progress, and where things just seemed to shoot from the ground. Every little station where we stopped, the native kiddies almost pestered us to death to buy their fruit; figs, grapes (both black and green), tomatoes, apples and melons being on sale for what seems to be ridiculously cheap prices. Grapes seem to grow everywhere and they do look so fine and luscious. Naturally one has to be careful and wash every kind of fruit before eating it.

I can’t tell you the feeling of pleasure and satisfaction we all had on coming amongst such luxuriant vegetation and the whole peacefulness of the business just poured a kind of soothing balm on our minds amongst the perpetual grind and sweat of army life and militarism with which we have been surfeited now for 4 years and over. One thing impressed me perhaps more than others – that the soil of a particular district through we which passed, was absolutely dark red in colour just like that very marked colour differences one notices when coming down the L.S.W.Rly. line from Salisbury and its chalk to Devon, glorious Devon. The fields and orchards of figs and oranges with the old farmyards so comfortably squatted amongst them were very dear reminders of home.

Well, now the Holy City itself! It’s just as I’ve pictured it, only perhaps the hills are much more steep than I imagined. The railway journey from Ludd to Jerusalem is an absolute marvel as regards engineering feats and I was never in such mountains in my life; but as this is only to be a short note I won’t elaborate here. Jerusalem has struck me as presenting a very marked similarity to Lanson, only hills more pronounce and of course much bigger. No matter how you approach it you have to climb fearful hills. There are splendid building in it, higher and more beautiful than Lanson possesses, I’m afraid, but its streets, especially the kind of suburbs and its villas and terraces remind me very much of the Dunheved and St. Thomas roads part of the old Lanson. Today I’ve visited the old city which is enclosed in walls and which is “Out of bounds” to troops except in parties of a dozen under a officer. I can’t go into details here but its simply grand and marvellous all of it, and the great difficulty is to be able to bring oneself to realise that these places on which one stands are really the places about which we have heard, read and dreamed since we were “tinies,” The Garden of Gethaemane for instance is kept splendidly, standing as it does at the foot of the famous Mount of Olives and it seems to fill one with reverence as one enters it. But all the same it is difficult to believe the actual fact. There is a splendid well in the garden the water of which is the coolest natural water I’ve tasted out here.

Have also visited today, Pools of Siloam and Betheeds, House and Court of Caiphas, Upper Room, Tombs of David, Zacharias and Absalom; the supposed sites of Calvary (there are 2 sites supposed; which is a matter of controversy); have also been on Mount Zion and Mount Moriah and can see the Mountains of Moab from my tent. Tomorrow we hope to climb Mount of Olives and get a view of the Dead Se and Jordan Valley and also visit Bethlehem. Must finish now, but I haven’t told you half my brain is in a whirl just now, needless to say. The weather is fine, it always is, and we are having a fine time. We go back on Monday next, so I hope to have a Sunday here. – Harry

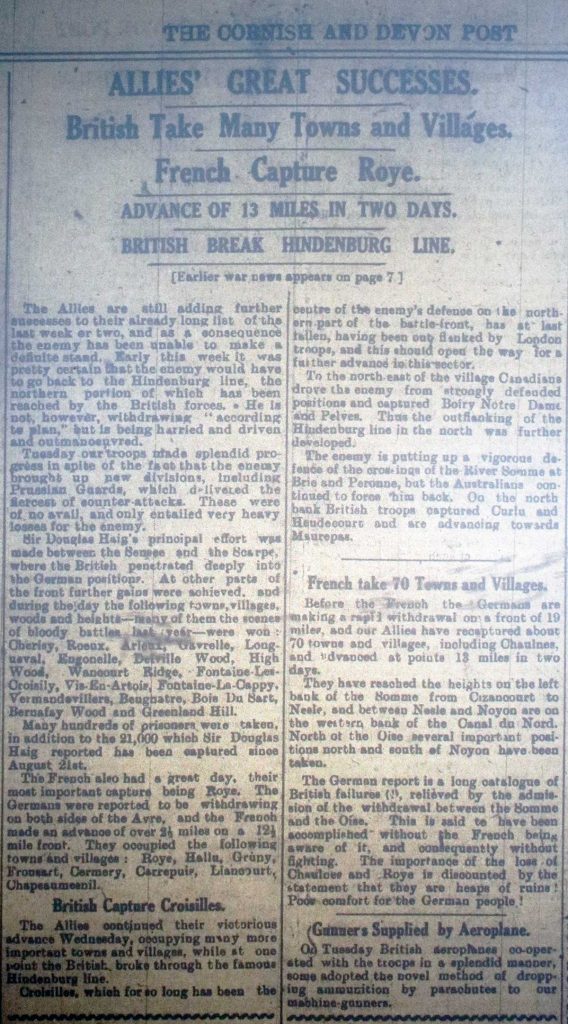

Cornish and Devon Post

The one thing that became very apparent right from the start of the war was the means of keeping those that were serving at the front in touch with their loved ones. Letter writing as we have seen was one way, even though these were to be heavily censored. The other medium used during the four years of conflict was the newspaper and for those from ‘Lanson’ this meant the ‘Cornish and Devon Post.’ For the average reader during the WWI era, newspapers were the best and most reliable option for up to date information. And, although nothing was completely safe from factual error and they didn’t have much choice in terms of how they got their news, many people saw their newspapers as being the most trustworthy way to stay informed. Literally hundreds of copies of the ‘Post’ were sent out every week, finding their way to all corners of the fighting. For those on the front, it was a means to stay grounded, a reminder of home. Driver James Avery, of the 23rd Battery R.F.A, writing home in at the beginning of the war said after receiving a copy of Cornish and Devon Post, “You should have seen the crowd around me” he said, “at the sight of a newspaper.” That single paper was read by hundreds, both men and officers, and handled until the print was hardly readable.”

Many of the personal letters written home were often passed on to the paper to be published, thus giving those on the home front a real attachment to the fronts. One avid writer was none other than former Launceston medic, Dr. Arthur Budd, who was serving with the 41st Field Ambulance, R.A.M.C., 13 Division, first at Gallipoli and then in Mesopotamia. The Post’s editor and owner at the time was Charles Orchard Sharp, and he and Arthur held a strong friendship from well before the war, and the two were avid correspondents to each other, and Charles went on to publish a series of letters that he received from Dr. Budd. Writing from Mesopotamia in early August 1916, it was clear how important receiving regular copies of the ‘Post’ were to Arthur when he wrote, “I often wonder how things are going with you all at home, and Lanson must be almost depleted of men of suitable age by now. The women are doing wonderful work, which will all help to terminate this bloody war. I was very interested in reading in the Cornish and Devon Post the agricultural demonstrations at Scarne by the women. One cannot overestimate the valuable work women are doing.”

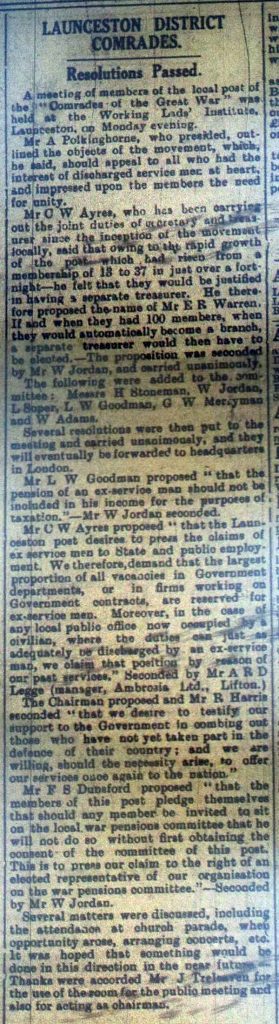

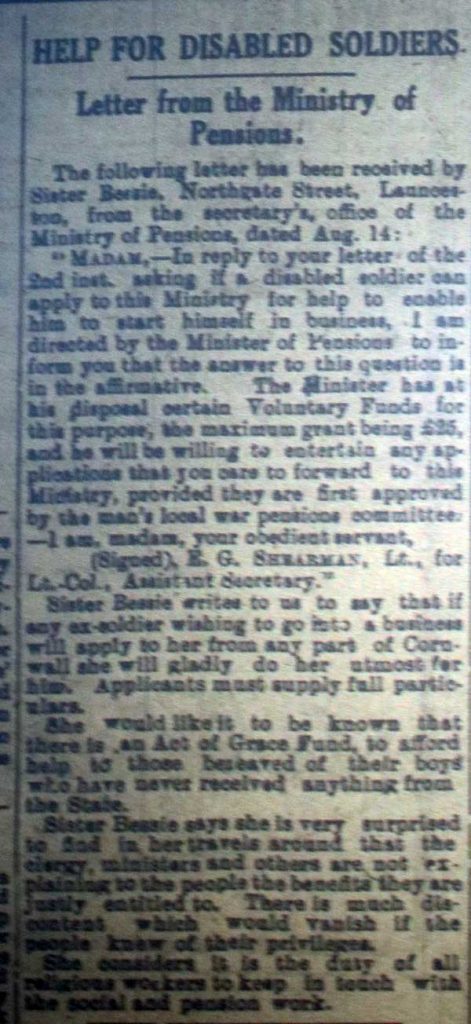

The ‘Post’ itself wasn’t immune from the war itself, a shortage of paper in the later years, meant that copies had to be reduced in size. Also, the paper was not immune to the draft and many of the workers such as former apprentice, Motor Driver Tom Parsons of the Army Service Corps, went off to fight. The owner, Charles Sharpe also had two sons fighting for their country, his eldest, George was a Gunner with the R.F.A. and Jack was Acting Bombardier (No. 748) of the 2nd Devon Battery, the 4th battalion, the Wessex Brigade. Jack tragically drowned in an accident whilst on a steamer traveling up the Euphrates River at Nasiriyah on August 15th, 1916. Below are three pdf copies of the paper covering the war period.

Launceston Weekly News, Saturday, September 26th, 1914

Cornish and Devon Post, Saturday, September 15th, 1917

Launceston Weekly News, Saturday, August 31st, 1918

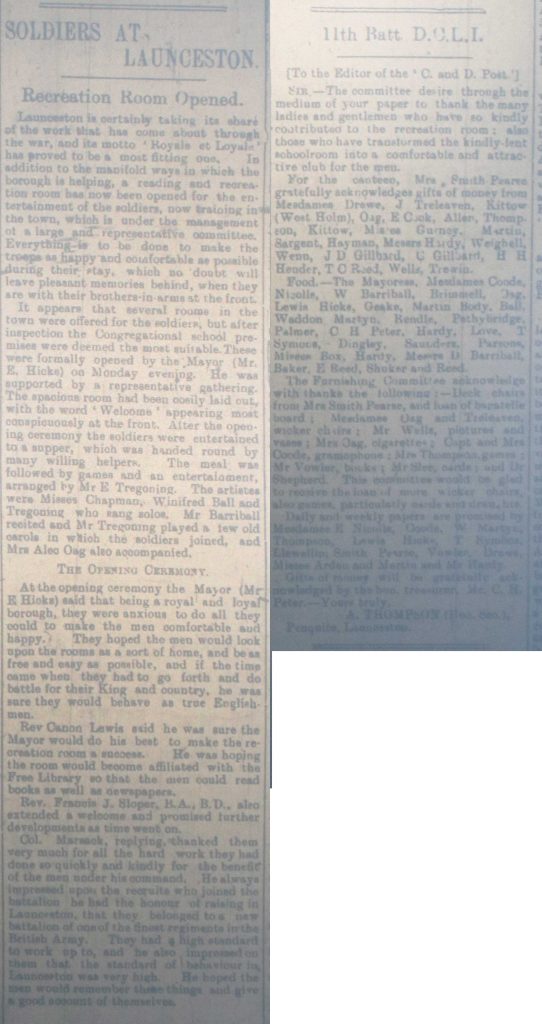

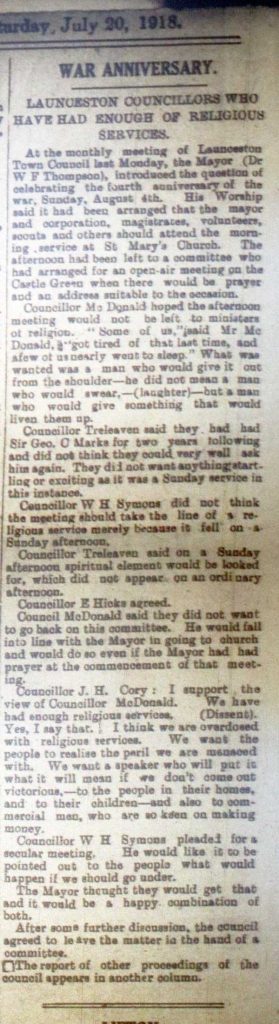

Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry 11th Battalion.

By the end of 1915 Launceston was being used as a training centre for Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry 11th Battalion under the command of Colonel E. L. Marsack. With the influx of so many men, the licensing laws were changed so that any publican could only serve the men of the Battalion between the hours of 12:30 to 1:30 p.m. and 6 to 9 p.m. With the well being of the men in consideration it was felt within the influential of the town that some form of entertainment should be arranged for them. On January 4th, 1916, a meeting was held to discuss the matter further, chaired by the Mayor, Edward Hicks. A scheme was adopted to provide a reading and recreation room and a committee was formed to obtain and manage the room and provide entertainments. The question of funding such an enterprise was discussed after the Town Clerk, Claude Peter suggested a recreation room could be run for about £1 or 25s. per week. St Thomas rector, Rev. Haworth suggested a street collection be made, to which the Mayor asked, to much laughter, what would be done if too much money were raised. It was agreed to leave the question of financing to the Finance and Games Sub-committee. Consequently, the Trustees of the Congregational Church in Castle Street offered the use of their Schoolroom and other rooms in Northgate Street which was accepted by the committee and the room was officially opened on Monday evening, January 10th. Although there were a few problems caused by the influx of men, with nearly 200 being raised during the three months that they were stationed at Launceston, for the most, it was a peaceful stay. The one notable exception came when a Boer War veteran, Private Richard Hill, was charged and found guilty of vagrancy where he was sentenced to two months hard labour.